Apartheid Space and Identity in Post-Apartheid Cape Town: the Case of the Bo-Kaap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnographic Analysis of Harare, Khayelitsha, and the Republic of South Africa

Ethnographic Analysis of Harare, Khayelitsha, and the Republic of South Africa University of Denver 2016 2 Table of Contents History ...................................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 2. Methods ................................................................................................................................. 5 3. Results .................................................................................................................................... 5 a. Changes in Khayelitsha ............................................................................................ 5 b. Changes in Siyakhathala Orphan Support ................................................................ 6 c. Community Leaders and Decision Making .............................................................. 6 d. History of South Africa ............................................................................................ 7 Demographics .......................................................................................................................8 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 8 2. Method .................................................................................................................................. -

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

(Special Trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300

Place Name Code Hub Surch Regional A KRIEK (special trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300 BFN No AANHOU WEN, Stellenbosch 7600 SSS No ABBOTSDALE 7600 SSS No ABBOTSFORD, East London 5241 ELS No ABBOTSFORD, Johannesburg 2192 JNB No ABBOTSPOORT 0608 PTR Yes ABERDEEN (48 hrs) 6270 PLR Yes ABORETUM 3900 RCB Town Ships No ACACIA PARK 7405 CPT No ACACIAVILLE 3370 LDY Town Ships No ACKERVILLE, Witbank 1035 WIR Town Ships Yes ACORNHOEK 1 3 5 1360 NLR Town Ships Yes ACTIVIA PARK, Elandsfontein 1406 JNB No ACTONVILLE & Ext 2 - Benoni 1501 JNB No ADAMAYVIEW, Klerksdorp 2571 RAN No ADAMS MISSION 4100 DUR No ADCOCK VALE Ext/Uit, Port Elizabeth 6045 PLZ No ADCOCK VALE, Port Elizabeth 6001 PLZ No ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 DUR No ADDNEY 0712 PTR Yes ADDO 2 5 6105 PLR Yes ADELAIDE ( Daily 48 Hrs ) 5760 PLR Yes ADENDORP 6282 PLR Yes AERORAND, Middelburg (Tvl) 1050 WIR Yes AEROTON, Johannesburg 2013 JNB No AFGHANI 2 4 XXXX BTL Town Ships Yes AFGUNS ( Special Trip ) 0534 NYL Town Ships Yes AFRIKASKOP 3 9860 HAR Yes AGAVIA, Krugersdorp 1739 JNB No AGGENEYS (Special trip) 8893 UPI Town Ships Yes AGINCOURT, Nelspruit (Special Trip) 1368 NLR Yes AGISANANG 3 2760 VRR Town Ships Yes AGULHAS (2 4) 7287 OVB Town Ships Yes AHRENS 3507 DBR No AIRDLIN, Sunninghill 2157 JNB No AIRFIELD, Benoni 1501 JNB No AIRFORCE BASE MAKHADO (special trip) 0955 PTR Yes AIRLIE, Constantia Cape Town 7945 CPT No AIRPORT INDUSTRIA, Cape Town 7525 CPT No AKASIA, Potgietersrus 0600 PTR Yes AKASIA, Pretoria 0182 JNB No AKASIAPARK Boxes 7415 CPT No AKASIAPARK, Goodwood 7460 CPT No AKASIAPARKKAMP, -

2011 Census - Cape Flats Planning District August 2013

City of Cape Town – 2011 Census - Cape Flats Planning District August 2013 Compiled by Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS), City of Cape Town 2011 Census data supplied by Statistics South Africa (Based on information available at the time of compilation as released by Statistics South Africa) Overview, Demographic Profile, Economic Profile, Dwelling Profile, Household Services Profile Planning District Description The Cape Flats Planning District is located in the southern part of the City of Cape Town and covers approximately 13 200 ha. It is bounded by the M5 in the west, N2 freeway to the north, Lansdowne Road and Weltevreden Road in the east and the False Bay coastline to the south. 1 Data Notes: The following databases from Statistics South Africa (SSA) software were used to extract the data for the profiles: Demographic Profile – Descriptive and Education databases Economic Profile – Labour Force and Head of Household databases Dwelling Profile – Dwellings database Household Services Profile – Household Services database Planning District Overview - 2011 Census Change 2001 to 2011 Cape Flats Planning District 2001 2011 Number % Population 509 162 583 380 74 218 14.6% Households 119 483 146 243 26 760 22.4% Average Household Size 4.26 3.99 In 2011 the population of Cape Flats Planning District was 583 380 an increase of 15% since 2001, and the number of households was 146 243, an increase of 22% since 2001. The average household size has declined from 4.26 to 3.99 in the 10 years. A household is defined as a group of persons who live together, and provide themselves jointly with food or other essentials for living, or a single person who lives alone (Statistics South Africa). -

Approved Belcom Decisions 27 August 2019 1

APPROVED DECISIONS OF THE MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE, BUILT ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE PERMIT COMMITTEE (BELCom) Held on Tuesday, 27 August 2019 in the 1st Floor Boardroom at the Offices of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport, Protea Assurance Building, Greenmarket Square, Cape Town scheduled for 09:00 MATTERS DISCUSSED 11 PROVINCIAL HERITAGE SITES: SECTION 27 PERMIT APPLICATIONS 11.1 Proposed Additions and Alterations at Erf 65106, 5 Ascot Road, Kenilworth: MA HM/ CAPE TOWN METROPOLITAN/KENILWORTH/ERF 65106 Case No: 19040407HB0507E DISCUSSION: Amongst other things, the following was discussed: • The Committee and the Applicant discussed the previous meeting’s decision of BELCom on 26 June 2019 and site report, in order to clarify the issues raised. The site report is to be forwarded to the Applicant immediately to assist with clarifying the Committee’s previous minuted response. WD 11.2 Proposed Rezoning from Residential 1 to General Residential in order to Develop a Guest House on Erf 4784, Paarl: MA HM / PAARL / ERF 4784 Case No: 18080107SB0831E RECORD OF DECISION: The Committee resolved to approve the application as a substantial improvement on previous proposals on condition that: 1. A veranda roof is to be added above the proposed first floor walkway. 2. The upstand gable in Section 2 is to be amended to depict a full gable. With the above conditions, heritage resources will no longer be negatively impacted. Revised drawings, including all the elevations are to be submitted to HOMs for approval. SB Approved BELCom Decisions_27 August 2019 1 11.3 Proposed Additions and Alterations, Erf 28173, 2 Dixon Road, Observatory: NM HM/ OBSERVATORY/ ERF 28173 Case No: 19043001HB0522E RECORD OF DECISION: 1. -

Rainy Day in Cape Town!

Parker Cottage’s Suggestions for a Rainy Day in Cape Town! Yes, it’s true. It even rains in Cape Town! When it does, there are actually quite a few fun things you can do. No need to bury your head under the duvet and hibernate: get out there! Parker Cottage Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za The Two Oceans Aquarium … Whilst it’s not enormous, our aquarium is one of the nicest ones I’ve ever visited because of the interesting way it’s laid out. There is a shark tank, pressurized tanks for ultra-deep sea creatures and also a kelp forest tank (my favourite) complete with wave machine where you can watch the fish swimming inside an underwater forest. Check out the daily penguin and shark-tank feedings to see our beautiful creatures in hungry action, or visit the touch-pool for an interactive experience. The staff are also really fun and the place is well maintained and clean. Dig deep to find your inner child and you’ll enjoy. Open every day from 09h30 – 18h00. Shark feedings on Sundays at 15h00, and penguin feedings daily at 11h45 and 14h30. Parker Cottage Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za Indoor markets … Cape Town is no stranger to the concept of the market and the pop-up shop. -

In the High Court of South Africa (Western Cape Division, Cape Town)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA (WESTERN CAPE DIVISION, CAPE TOWN) CASE NO: In the matter between: SOUTHERN AFRICA LITIGATION CENTRE Applicant and THE MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS First Respondent THE DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HOME AFFAIRS Second Respondent AUGUSTINUS PETRUS MARIA KOUWENHOVEN Third Respondent ___________________________________________________________________ NOTICE OF MOTION ___________________________________________________________________ BE PLEASED TO TAKE NOTICE that, on a date to be arranged with the Registrar of this Honourable Court, the Applicant intends to make application to this Court for an order in the following terms: 1. Reviewing and setting aside the decision of the Second Respondent taken on or about 30 August 2017 to issue to the Third Respondent a visa in terms of section 11(6) of the Immigration Act, No. 13 of 2002 (“the Immigration Act”). Lawyers for Human Rights (021) 424-8561 2 2. Declaring the impugned decision to be unlawful, inconsistent with the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (“the Constitution”), and invalid. 3. Reviewing and setting aside the failure of the Second Respondent to declare the Third Respondent undesirable in terms of section 30(1)(f) and section 30(1)(g) of the Immigration Act. 4. Substituting the failure of the Second Respondent to declare the Third Respondent undesirable in terms of section 30(1)(f) and section 30(1)(g) of the Immigration Act with the following decisions: 4.1 the Third Respondent is declared to be an undesirable person; and 4.2 the Third Respondent does not qualify for a port of entry visa, visa, admission into the Republic or a permanent residence permit. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, and EMPIRE: a PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, AND EMPIRE: A PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R. Stromberg* As we approach the centennial of the Second Anglo–Boer War (Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, or “Second War for Freedom”), reassessment of the South African experience seems in order. Whether the recent surrender by Afrikaner political leaders of their “central theme” and the dismantling of their grandiose Apartheid state will lead to heaven on earth (as some of the Soweto “comrades” expected), or even to a merely tolerable multiracial polity, remains in doubt. Historians have tended to look for the origins of South Africa’s “very strange society” in the interaction of various peoples and political forces on a rapidly changing frontier, especially in the 19th century. APPROACHES TO SOUTH AFRICAN FRONTIER HISTORY At least two major schools of interpretation developed around these issues. The first, Cape Liberals, viewed the frontier Boers largely as rustic ruffians who abused the natives and disrupted or- derly economic progress only to be restrained, at last, by humani- tarian and legalistic British paternalists. Afrikaner excesses, therefore, were the proximate cause and justification of the Boer War and the consolidation of British power over a united South Africa. The “imperial factor” on this view was liberal and pro- gressive in intent if not in outcome. The opposing school were essentially Afrikaner nationalists who viewed the Boers as a uniquely religious people thrust into a dangerous environment where they necessarily resorted to force to overcome hostile African tribes and periodic British harassment. The two traditions largely agreed on the centrality of the frontier, but differed radically on the villains and heroes.1 Beginning in the 1960s and ’70s, a third position was heard, that of younger “South Africanists” driven to distraction (and some *Joseph R. -

THE STREETS ARE COLD, the GANGS ARE WARM: an INTERROGATION of WHY PEOPLE JOIN GANGS Sanna Strand SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2014 THE STREETS ARE COLD, THE GANGS ARE WARM: AN INTERROGATION OF WHY PEOPLE JOIN GANGS Sanna Strand SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Recommended Citation Strand, Sanna, "THE STREETS ARE COLD, THE GANGS ARE WARM: AN INTERROGATION OF WHY PEOPLE JOIN GANGS" (2014). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2029. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2029 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: THE STREETS ARE COLD, THE GANGS ARE WARM THE STREETS ARE COLD, THE GANGS ARE WARM: AN INTERROGATION OF WHY PEOPLE JOIN GANGS Sanna Strand Advisor: Kolade Arogundade, SIT Advisor and Lecturer, University of Cape Town Lecturer In partial fulfillment fog the requirements for: South Africa: Multicultural and Human Rights SIT Study Abroad, a Program for World Learning Cape -

Film Locations in TMNP

Film Locations in TMNP Boulders Boulders Animal Camp and Acacia Tree Murray and Stewart Quarry Hillside above Rhodes Memorial going towards Block House Pipe Track Newlands Forest Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Noordhoek Beach Rocks Misty Cliffs Beach Newlands Forest Old Buildings Abseil Site on Table Mountain Noordhoek beach Signal Hill Top of Table Mountain Top of Signal Hill looking towards Town Animal Camp looking towards Devils Peak Tafelberg Road Lay Byes Noordhoek beach with animals Deer Park Old Zoo site on Groote Schuur Estate : External Old Zoo Site Groote Schuur Estate ; Internal Oudekraal Oudekraal Gazebo Rhodes Memorial Newlands Forest Above Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Kramat on Signal Hill Newlands Forest Platteklip Gorge on the way to the top of Table Mountain Signal Hill Oudekraal Deer Park Misty Cliffs Misty Cliffs Tracks off Tafelberg Road coming down Glencoe Quarry Buffels Bay at Cape Point Silvermine Dam Desk on Signal Hill Animal Camp Cecelia Forest Cecelia Forest Cecilia Forest Buffels Bay at Cape Point Link Road at Cape Point Cape Point at the Lighthouse Precinct Acacia Tree in the Game camp Slangkop Slangkop Boardwalk near Kommetjie Kleinplaas Dam Devils Peak Devils Peak Noordhoek LookOut Chapmans Peak Noordhoek to Hout Bay Dias Beach at CapePoint Cape Point Cape Point Oudekraal to Twelve Apostles Silvermine Dam . -

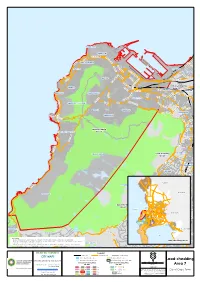

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication .