Ethnicity in Namibia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

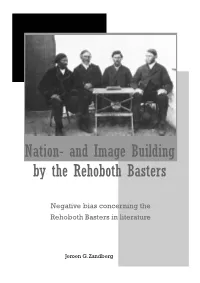

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature Jeroen G. Zandberg Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature 1. Introduction Page 3 2. How do I define a negative biased statement? …………………..5 3. The various statements ……………………………………… 6 3.1 Huibregtse ……………………………………… ……. 6 3.2 DeWaldt ……………………………………………. 9 3.3 Barnard ……………………………………………. 12 3.4 Weiss ……………………………………………. 16 4. The consequences of the statements ………………………… 26 4.1 Membership application to the UNPO ……………27 4.2 United Nations ………………………………………29 4.3 Namibia ……………………………………………..31 4.4 Baster political identity ………………………………..34 5. Conclusion and recommendation ……………………………...…38 Bibliography …………………………………………………….41 Rehoboth journey ……………………………………………...43 Picture on front cover: The Kapteins Council in 1876. From left to right: Paul Diergaardt, Jacobus Mouton, Hermanus van Wijk, Christoffel van Wijk. On the table lies the Rehoboth constitution (the Paternal Laws) Jeroen Gerk Zandberg 2005 ISBN – 10: 9080876836 ISBN – 13: 9789080876835 2 1. Introduction The existence of a positive (self) image of a people is very important in the successful struggle for self-determination. An image can be constructed through various methods. This paper deals with the way in which an incorrect image of the Rehoboth Basters was constructed via the literature. Subjects that are considered interesting or popular, usually have a great number of different publications and authors. A large quantity of publications almost inevitably means that there is more information available on that specific topic. A large number of publications usually also indicates a great amount of authors who bring in many different views and interpretations. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 490 | FEBRUARY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE w w w .usip.org North Korea in Africa: Historical Solidarity, China’s Role, and Sanctions Evasion By Benjamin R. Young Contents Introduction ...................................3 Historical Solidarity ......................4 The Role of China in North Korea’s Africa Policy .........7 Mutually Beneficial Relations and Shared Anti-Imperialism..... 10 Policy Recommendations .......... 13 The Unknown Soldier statue, constructed by North Korea, at the Heroes’ Acre memorial near Windhoek, Namibia. (Photo by Oliver Gerhard/Shutterstock) Summary • North Korea’s Africa policy is based African arms trade, construction of owing to African governments’ lax on historical linkages and mutually munitions factories, and illicit traf- sanctions enforcement and the beneficial relationships with African ficking of rhino horns and ivory. Kim family regime’s need for hard countries. Historical solidarity re- • China has been complicit in North currency. volving around anticolonialism and Korea’s illicit activities in Africa, es- • To curtail North Korea’s illicit activ- national self-reliance is an under- pecially in the construction and de- ity in Africa, Western governments emphasized facet of North Korea– velopment of Uganda’s largest arms should take into account the histor- Africa partnerships. manufacturer and in allowing the il- ical solidarity between North Korea • As a result, many African countries legal trade of ivory and rhino horns and Africa, work closely with the Af- continue to have close ties with to pass through Chinese networks. rican Union, seek cooperation with Pyongyang despite United Nations • For its part, North Korea looks to China, and undercut North Korean sanctions on North Korea. -

RUMOURS of RAIN: NAMIBIA's POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre Du Pisani

SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani THE .^-y^Vr^w DIE SOUTH AFRICAN i^W*nVv\\ SUID AFRIKAANSE INSTITUTE OF f I \V\tf)) }) INSTITUUT VAN INTERNATIONAL ^^J£g^ INTERNASIONALE AFFAIRS ^*^~~ AANGELEENTHEDE SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES NO 3 RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani ISBN NO.: 0-908371-88-8 February 1991 Toe South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 Braamfontein 2017 Johannesburg South Africa CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 POUTICS IN AFRICA'S NEWEST STATE 2 National Reconciliation 2 Nation Building 4 Labour in Namibia 6 Education 8 The Local State 8 The Judiciary 9 Broadcasting 10 THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALM - AN UNBALANCED INHERITANCE 12 Mining 18 Energy 19 Construction 19 Fisheries 20 Agriculture and Land 22 Foreign Exchange 23 FOREIGN RELATIONS - NAMIBIA AND THE WORLD 24 CONCLUSIONS 35 REFERENCES 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 ANNEXURES I - 5 and MAP 44 INTRODUCTION Namibia's accession to independence on 21 March 1990 was an uplifting event, not only for the people of that country, but for the Southern African region as a whole. Independence brought to an end one of the most intractable and wasteful conflicts in the region. With independence, the people of Namibia not only gained political freedom, but set out on the challenging task of building a nation and defining their relations with the world. From the perspective of mediation, the role of the international community in bringing about Namibia's independence in general, and that of the United Nations in particular, was of a deep structural nature. -

Introduction One Setting the Stage

Notes Introduction 1. For further reference, see, for example, MacKay 2002. 2. See also Engle 2010 for this discussion. 3. I owe thanks to Naomi Kipuri, herself an indigenous Maasai, for having told me of this experience. 4. In the sense as this process was first described and analyzed by Fredrik Barth (1969). 5. An in-depth and updated overview of the state of affairs is given by other sources, such as the annual IWGIA publication, The Indigenous World. 6. The phrase refers to a 1972 cross-country protest by the Indians. 7. Refers to the Act that extinguished Native land claims in almost all of Alaska in exchange for about one-ninth of the state’s land plus US$962.5 million in compensation. 8. Refers to the court case in which, in 1992, the Australian High Court for the first time recognized Native title. 9. Refers to the Berger Inquiry that followed the proposed building of a pipeline from the Beaufort Sea down the Mackenzie Valley in Canada. 10. Settler countries are those that were colonized by European farmers who took over the land belonging to the aboriginal populations and where the settlers and their descendents became the majority of the population. 11. See for example Béteille 1998 and Kuper 2003. 12. I follow the distinction as clarified by Jenkins when he writes that “a group is a collectivity which is meaningful to its members, of which they are aware, while a category is a collectivity that is defined according to criteria formu- lated by the sociologist or anthropologist” (2008, 56). -

AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE SEMINAR the Rehoboth Rebellion

The Gubblns Library, AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE SEMINAR The Rehoboth Rebellion by P. Pearson At dawn on the 5th of April 1925, a force of 621 men comprising citizen force troops and police surrounded the town of Rehoboth in South West Africa. Their object was to secure the arrest of three men who had failed to respond to summonses issued under the stock branding proclamation. Seven days previously a large group of supporters had prevented three local policemen from entering the building where the men were staying. In response to this act of defiance, the Administrator had mobilized the citizen force in nine districts and declared (2) martial law in Rehoboth. At 7am a messenger entered the town carrying an ultimatum from Col. de Jager, commander of the troops. It called for an unconditional surrender by 8am. The rebels asked for more time in order to evacuate the women and children, but at 8.15am three aeroplanes fitted with machine guns flew low over the town and the soldiers charged. Faced with this vastly superior force, the rebels offered little resistance, and no shots were fired. The soldiers and policemen were spurred on by de Jager to attack their opponents with sticks arid rifle butts. Women and children who surrounded the rebel headquarters in an attempt to (4) protect their menfolk inside were also quickly dealt with in this way. Six hundred and thirty two people were arrested on charges of illegal assembly and 304 firearms were confiscated. All of the weapons were subsequently declared 'unservicablef and destroyed. Organised resistance had begun some twenty months earlier on the 17th of August 1923. -

IMPACT REPORT a Word from the Founder and Director|

2017 - 2020 IMPACT REPORT A word from the founder and director| In October 2017 as we were preparing to launch a collaborative " network of journalists dedicated to pursuing and publishing the work of other reporters facing threats, prison or murder, prominent Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was horrifically silenced with a car bomb. Her murder was a cruel and stark reminder of how tenuous the free flow of information can be when democratic systems falter. We added Daphne to the sad and long list of journalists whose work Forbidden Stories is committed to continuing. For five months, we coordinated a historic collaboration of 45 journalists from 18 news organizations, aimed at keeping Daphne Caruana Galizia’s stories alive. Her investigations, as a result of this, ended up on the front pages of the world’s most widely-read newspapers. Seventy-four million people heard about the Daphne Project worldwide. Although her killers had hoped to silence her stories, the stories ended up having an echo way further than Malta. LAURENT RICHARD Forbidden Stories' founder Three years later, the journalists of the Daphne Project continue and executive director. to publish new revelations about her murder and pursue the investigations she started. Their explosive role in taking down former Maltese high-ranking government officials confirms that collaboration is the best protection against impunity. 2 2017-2020 Forbidden Stories Impact Report A word from the founder and director| That’s why other broad collaborative On a smaller scale, we have investigations followed. developed rapid response projects. We investigated the circumstances The Green Blood Project, in 2019, pursued behind the murders of Ecuadorian, the stories of reporters in danger for Mexican and Ghanaian journalists; investigating environmental scandals. -

Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 1 Spring 2010 Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Edwin Odhiambo Abuya, Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections?, 8 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 122 (2010). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol8/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2010 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 8, Issue 2 (Spring 2010) Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya* Asiyekubali kushindwa si msihindani.1 I. INTRODUCTION ¶1 Can African States hold free and fair elections? To put it another way, is it possible to conduct presidential elections in Africa that meet internationally recognized standards? These questions can be answered in the affirmative. However, in order to safeguard voting rights, specific reforms must be adopted and implemented on the ground. In keeping with international legal standards on democracy,2 the constitutions of many African states recognize the right to vote.3 This right is reflected in the fact that these states hold regular elections. The right to vote is fundamental in any democratic state, but an entitlement does not guarantee that right simply by providing for elections. -

IPPR Briefing Paper NO 44 Political Party Life in Namibia

Institute for Public Policy Research Political Party Life in Namibia: Dominant Party with Democratic Consolidation * Briefing Paper No. 44, February 2009 By André du Pisani and William A. Lindeke Abstract This paper assesses the established dominant-party system in Namibia since independence. Despite the proliferation of parties and changes in personalities at the top, three features have structured this system: 1) the extended independence honeymoon that benefits and is sustained by the ruling SWAPO Party of Namibia, 2) the relatively effective governance of Namibia by the ruling party, and 3) the policy choices and political behaviours of both the ruling and opposition politicians. The paper was funded in part by the Danish government through Wits University in an as yet unpublished form. This version will soon be published by Praeger Publishers in the USA under Series Editor Kay Lawson. “...an emergent literature on African party systems points to low levels of party institutionalization, high levels of electoral volatility, and the revival of dominant parties.” 1 Introduction Political reform, democracy, and governance are centre stage in Africa at present. African analysts frequently point to the foreign nature of modern party systems compared to the pre-colonial political cultures that partially survive in the traditional arenas especially of rural politics. However, over the past two decades multi-party elections became the clarion call by civil society (not to mention international forces) for the reintroduction of democratic political systems. This reinvigoration of reform peaked just as Namibia gained its independence under provisions of the UN Security Council Resolution 435 (1978) and the supervision of the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG). -

Multiparty Democracy and Elections in Namibia

MULTIPARTY DEMOCRACY AND ELECTIONS IN NAMIBIA ––––––––––––– ❑ ––––––––––––– Published with the assistance of NORAD and OSISA ISBN 1-920095-02-0 Debie LeBeau 9781920 095024 Edith Dima Order from: [email protected] EISA RESEARCH REPORT No 13 EISA RESEARCH REPORT NO 13 i MULTIPARTY DEMOCRACY AND ELECTIONS IN NAMIBIA ii EISA RESEARCH REPORT NO 13 EISA RESEARCH REPORT NO 13 iii MULTIPARTY DEMOCRACY AND ELECTIONS IN NAMIBIA BY DEBIE LEBEAU EDITH DIMA 2005 iv EISA RESEARCH REPORT NO 13 Published by EISA 2nd Floor, The Atrium 41 Stanley Avenue, Auckland Park Johannesburg, South Africa 2006 P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: 27 11 482 5495 Fax: 27 11 482 6163 Email: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 1-920095-02-0 EISA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2005 EISA is a non-partisan organisation which seeks to promote democratic principles, free and fair elections, a strong civil society and good governance at all levels of Southern African society. –––––––––––– ❑ –––––––––––– Cover photograph: Yoruba Beaded Sashes Reproduced with the kind permission of Hamill Gallery of African Art, Boston, MA USA EISA Research Report, No. 13 EISA RESEARCH REPORT NO 13 v CONTENTS List of acronyms viii Acknowledgements x Preface xi 1. Background to multiparty democracy in Namibia 1 Historical background 1 The electoral system and its impact on gender 2 The ‘characters’ of the multiparty system 5 2. -

Namibia Presidential and National Assembly Elections

Namibia Presidential and National Assembly Elections 27 November 2019 MAP OF NAMIBIA ii CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. V EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... IX CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 INVITATION .................................................................................. 1 TERMS OF REFERENCE ....................................................................... 1 ACTIVITIES .................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 2 – POLITICAL BACKGROUND............................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 3 BRIEF POLITICAL HISTORY ................................................................... 3 POLITICAL CONTEXT OF THE 2019 ELECTIONS ................................................ 4 POLITICAL PARTIES AND PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES CONTESTING THE 2019 ELECTIONS ....... 5 CHAPTER 3 – THE ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ............................................... 6 THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR ELECTIONS ..................................................... 6 THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION