Rhodiola Rosea in Nunatsiavut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variability of Major Phenyletanes and Phenylpropanoids in 16-Year-Old Rhodiola Rosea L

molecules Article Variability of Major Phenyletanes and Phenylpropanoids in 16-Year-Old Rhodiola rosea L. Clones in Norway Abdelhameed Elameen 1,* , Vera M. Kosman 2, Mette Thomsen 3, Olga N. Pozharitskaya 4 and Alexander N. Shikov 5 1 NIBIO, Norwegian Institute for Bioeconomy Research, Høghskoleveien 7, N-1431 Ås, Norway 2 St. Petersburg Institute of Pharmacy, Leningrad Region, Vsevolozhsky District, P 245 188663 Kuzmolovo, Russia; [email protected] 3 NIBIO, Norwegian Institute for Bioeconomy Research, Øst Apelsvoll, 2849 Kapp, Norway; [email protected] 4 Murmansk Marine Biological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (MMBI RAS), Vladimirskaya, 17, 183010 Murmansk, Russia; [email protected] 5 St. Petersburg State Chemical Pharmaceutical University, Prof. Popov, 14, 197376 Saint-Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +479-020-0875 Academic Editors: Francesco Cacciola and Lillian Barros Received: 17 June 2020; Accepted: 28 July 2020; Published: 30 July 2020 Abstract: Rhodiola rosea L. (roseroot) is an adaptogen plant belonging to the Crassulaceae family. The broad spectrum of biological activity of R. rosea is attributed to its major phenyletanes and phenylpropanoids: rosavin, salidroside, rosin, cinnamyl alcohol, and tyrosol. In this study, we compared the content of phenyletanes and phenylpropanoids in rhizomes of R. rosea from the Norwegian germplasm collection collected in 2004 and in 2017. In general, the content of these bioactive compounds in 2017 was significantly higher than that observed in 2004. The freeze-drying method increased the concentration of all phenyletanes and phenylpropanoids in rhizomes compared 1 with conventional drying at 70 ◦C. As far as we know, the content of salidroside (51.0 mg g− ) observed in this study is the highest ever detected in Rhodiola spp. -

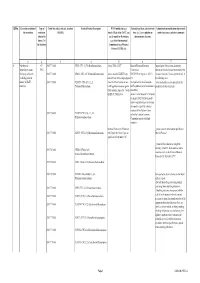

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

Chapter 16 Demand and Availability of Rhodiola Rosea L

CHAPTER 16 DEMAND AND AVAILABILITY OF RHODIOLA ROSEA L. RAW MATERIAL BERTALAN GALAMBOSI Agrifood Research Finland, Ecological Production Karilantie 2A, FIN-50600 Mikkeli, Finland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Rhodiola rosea L. roseroot, (Golden root or Arctic root) is a herbaceous perennial plant of the family Crassulaceae. The yellow-flowered roseroot species is a circumpolar species of cool temperate and sub-arctic areas of the northern hemisphere, including North America, Greenland, Iceland and the Altai, Tien-Shan, Himalaya mountains in Asia. The European distribution includes Scandinavia and most of the mountains of Central Europe. Roseroot has traditionally been used in Russia and Mongolia for the treatment of long-term illness and weakness caused by infection. Rhodiola radix and rhizome is a multipurpose medicinal herb with adaptogenic properties: it increases the body’s nonspecific resistance and normalizes body functions. A special emphasis in pharmacological research has been put on roseroot in the former Soviet Union. Several clinical studies have documented roseroot’s beneficial effects on memory and learning, immune- response stress and cancer therapy. Rhodiola preparations have widely been used to increase the stress tolerance of the cosmonauts. Salidroside and its precursor tyrosol, and cinnamic glycosides (rosin, rosavin and rosarin) have been identified from the roots and rhizome. Other important constituents are flavonoids, tannins and gallic acid and its esters (Brown et al. 2002). Based on the documented pharmacological effects and its safe use, the commercial interest for roseroot-based products has quickly increased worldwide. Presently one of the biggest problems is to meet the raw-material requirement for the growing industrial demand. -

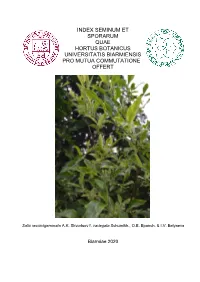

Index Seminum Et Sporarum Quae Hortus Botanicus Universitatis Biarmiensis Pro Mutua Commutatione Offert

INDEX SEMINUM ET SPORARUM QUAE HORTUS BOTANICUS UNIVERSITATIS BIARMIENSIS PRO MUTUA COMMUTATIONE OFFERT Salix recurvigemmata A.K. Skvortsov f. variegata Schumikh., O.E. Epanch. & I.V. Belyaeva Biarmiae 2020 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education «Perm State National Research University», A.G. Genkel Botanical Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ СПИСОК СЕМЯН И СПОР, ПРЕДЛАГАЕМЫХ ДЛЯ ОБМЕНА БОТАНИЧЕСКИМ САДОМ ИМЕНИ А.Г. ГЕНКЕЛЯ ПЕРМСКОГО ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Syringa vulgaris L. ‘Красавица Москвы’ Пермь 2020 Index Seminum 2020 2 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education «Perm State National Research University», A.G. Genkel Botanical Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ Дорогие коллеги! Ботанический сад Пермского государственного национального исследовательского университета был создан в 1922 г. по инициативе и под руководством проф. А.Г. Генкеля. Здесь работали известные ученые – ботаники Д.А. Сабинин, В.И. Баранов, Е.А. Павский, внесшие своими исследованиями большой вклад в развитие биологических наук на Урале. В настоящее время Ботанический сад имени А.Г. Генкеля входит в состав регионального Совета ботанических садов Урала и Поволжья, Совет ботанических садов России, имеет статус научного учреждения и особо охраняемой природной территории. Основными научными направлениями работы являются: интродукция и акклиматизация растений, -

Rhodiola Rosea L

u Ottawa l.'Univcrsilc! cnnnrlicwu- Cnnodn's univcrsiiy FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES ls=l FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L*University canadiennc Canada's university Vicky J. Filion AUTEUR DETATHISET/ AUTHOR OF THESIS" M_.Sc. (Biology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Biology TAMTE"TCOLirDpARTEMENT~^ACUITY, S*CHOdi~DEWRTMENT" A Novel Phytochemical and Ecological Study of the Nunavik Medicinal Plant Rhodiola rosea L. TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS _____„„____Dr._ J. Arnason A. Cuerrier EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS Dr. C. Charest Dr. J. Kerr Dr. N. Cappuccino _Garjr\V^SJatCT_ Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales I Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies A Novel Phytochemical and Ecological Study of the Nunavik Medicinal Plant Rhodiola rosea L. Vicky J. Filion Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the M.Sc. degree in the Ottawa-Carleton Institute of Biology These soumise a la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales Universite d'Ottawa en vue de l'obtention de la maitrise es sciences Institut de biologie d'Ottawa-Carleton © Vicky J. Filion, Ottawa, Canada, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50879-4 -

Rhodiola Rosea: a Phytomedicinal Overview By

Rhodiola rosea: A Phytomedicinal Overview by Richard P. Brown, M.D., Patricia L. Gerbarg, M.D., and Zakir Ramazanov, Ph.D., D.S. Rhodiola rosea L., also known as "golden root" or "roseroot" belongs to the plant family Crassulaceae.1 R. rosea grows primarily in dry sandy ground at high altitudes in the arctic areas of Europe and Asia.2 The plant reaches a height of 12 to 30 inches (70cm) and produces yellow blossoms. It is a perennial with a thick rhizome, fragrant when cut. The Greek physician, Dioscorides, first recorded medicinal applications of rodia riza in 77 C.E. in De Materia Medica.3 Linnaeus renamed it Rhodiola rosea, referring to the rose-like attar (fragrance) of the fresh cut rootstock.4 For centuries, R. rosea has been used in the traditional medicine of Russia, Scandinavia, and other countries. Between 1725 and 1960, various medicinal applications of R. rosea appeared in the scientific literature of Sweden, Norway, France, Germany, the Soviet Union, and Iceland.2,4-12 Since 1960, more than 180 pharmacological, phytochemical, and clinical studies have been published. Although R. rosea has been extensively studied as an adaptogen with various health-promoting effects, its properties remain largely unknown in the West. In part this may be due to the fact that the bulk of research has been published in Slavic and Scandinavian languages. This review provides an introduction to some of the traditional uses of R. rosea, its phytochemistry, scientific studies exploring its diverse physiological effects, and its current and future medical applications. Rhodiola rosea in Traditional Medicine Traditional folk medicine used R. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

Integrative Approaches to Management of Depression & Anxiety

INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE APPROACH TO DEPRESSION & ANXIETY GREG SHUMER, M.D., M.H.S.A CLINICAL ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY MEDICINE JUNE 20, 2018 OUTLINE • Case Presentations • Background • Review of Standard Treatments • Herbs & Supplements • Other Modalities • Back to the Cases DISCLOSURES • No financial or other disclosures to make CASE 1: SL • Treatments: • CBT & Mindfulness-based yoga program in 2014 • HPI: 41yo healthy female presenting for • Started on Zoloft 50 mg and it helped, but has since consultation regarding anxiety, panic attacks, PTSD, discontinued and fatigue • Xanax as needed, uses rarely • History of physical abuse from brother (8-11yo) and Currently sees a therapist weekly sexual / emotional abuse from ex-boyfriend (25- • 35yo) • Now in a new relationship and symptoms worsening, would like to know other options • Developed symptoms of weekly panic attacks, PTSD, and anxiety in 2013 • Also with worsening tension / aches and pains in shoulders and neck, would like recommendations • PHQ-9 10, GAD-7 12 CASE 2: JN • 46yo female w/ history of migraines, insomnia, and depression previously on Celexa (discontinued 1 year ago) presents for worsening depression & anxiety • ROS: • Reports baseline “anxiety & irritability.” Celexa • Frequent nighttime awakenings; cannot fall back to helped, but felt sluggish & worse in some ways – sleep flat affect, less productive at work • Hot flashes intermittently and worsening • Symptoms gradually worsening since d/c Celexa • PHQ9: 4 • Snapping at kids and husband for small things, like • GAD7: 18 wrapping presents too slowly • Tried CBT, did not like it / not helpful • No current exercise. Diet is OK CASE 3: MR • 23yo male with worsening depression, lack of energy, over-sleeping • Low self-esteem, has difficulty leaving home. -

Identifying Abiotic and Biotic Factors Associated with Leedy's Roseroot

Identifying Abiotic and Biotic Factors Associated with Leedy’s Roseroot (Rhodiola integrifolia subsp. leedyi (Rosend. & J.W. Moore) Kartesz) at Glenora Cliffs, Glenora, New York by Kali Z. Mattingly Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfwm/article-supplement/432994/pdf/10_3996022018-jfwm-010_s12 by guest on 01 October 2021 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York May 2016 Approved: Department of Environmental and Forest Biology _________________________________ ________________________________ Donald J. Leopold, Department Chair Douglas Morrison, Chair & Major Professor Examining Committee ________________________________ S. Scott Shannon, Dean The Graduate School ProQuest Number: 10130756 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfwm/article-supplement/432994/pdf/10_3996022018-jfwm-010_s12 by guest on 01 October 2021 The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10130756 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several people have been fundamental in the completion of this thesis. I thank my major professor, Don Leopold, for the opportunity to join his lab and for his guidance over the past two years. -

00044821 Prodoc 00052843

UNDP Project Document Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan United Nations Development Programme Global Environment Facility PIMS 2898 Atlas Award 00044821 Atlas Project No: 00052843 Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in the Kazakhstani Sector of the Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Brief description The goal of the project is to help secure the globally significant biodiversity values of the Kazakhstan. The project’s objective is to enhance the sustainability and conservation effectiveness of Kazakhstan’s national PA system by demonstrating sustainable and replicable approaches to conservation management in the protected areas in the Kazakhstani sector of Altai-Sayan ecoregion.The project will produce five outcomes: the protected area network will be expanded and PA management effectiveness will be enhanced; awareness of and support for biodiversity conservation and PAs will be increased among all stakeholders; the enabling environment for strengthening the national protected area system will be enhanced; community involvement in biodiversity conservation will be increased and opportunities for sustainable alternative livelihoods within PAs and buffer zones will be facilitated; and networking and collaboration among protected areas will be improved, and the best practices and lessons learned will be disseminated and replicated in other locations within the national protected area system. 1 Table of Contents SECTION I: ELABORATION OF THE NARRATIVE .......................................................................... 5 PART -

Medicinal Herbs with Anti-Depressant Effects

J Herbmed Pharmacol. 2020; 9(4): 309-317. http://www.herbmedpharmacol.com doi: 10.34172/jhp.2020.39 Journal of Herbmed Pharmacology Medicinal herbs with anti-depressant effects Mahbubeh Setorki* ID Department of Biology, Izeh Branch, Islamic Azad University, Izeh, Iran A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article Type: Depression is a life-threatening chronic illness which affects people worldwide. Drugs used to Review treat this disease have multiple side effects and may cause drug-drug or drug-food interactions. Additionally, only 30% of patients respond adequately to the existing drugs and the remaining Article History: do not achieve complete recovery. Thus, finding effective treatments that have adequate Received: 10 November 2018 efficacy, fewer side effects and lower cost seem to be necessary. The purpose of this study was Accepted: 24 January 2019 to review animal and double-blind clinical studies on the anti-depressant effects of medicinal herbs. In this study, validated scientific articles indexed in PubMed, SID, Web of Science and Keywords: Scopus databases were reviewed. A database search was performed using the following terms: Depression clinical trials, depression, major depressive disorder, essential oil, extract and medicinal plant. Clinical trials Positive effects of a number of herbs and their active compounds such as St John’s-wort, saffron, Medicinal plants turmeric, ginkgo, chamomile, valerian, Lavender, Echium amoenum and Rhodiola rosea L. in Herbal medicines improvement of symptoms of mild, moderate or major depression have been shown in clinical trials. The above plants show antidepressant effects and have fewer side effects than synthetic drugs. -

Index Seminum Et Sporarum Perm, 2013

INDEX SEMINUM ET SPORARUM QUAE HORTUS BOTANICUS UNIVERSITATIS BIARMIENSIS PRO MUTUA COMMUTATIONE OFFERT СПИСОК СЕМЯН И СПОР , предлагаемых для обмена Ботаническим садом имени проф . А.Г. Генкеля Пермского государственного национального исследовательского университета Пермь , Россия Biarmiae 2013 Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education «Perm State University», Botanic Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ Дорогие друзья ботанических садов , Дорогие коллеги ! Ботанический сад Пермского государственного национального исследовательского университета был создан в 1922 г. по инициативе и под руководством проф . А.Г. Генкеля . Здесь работали известные ученые – ботаники Д.А. Сабинин , В.И. Баранов , Е.А. Павский , внесшие своими исследованиями большой вклад в развитие биологических наук на Урале . В настоящее время Ботанический сад имени профессора А.Г. Генкеля входит в состав регионального Совета ботанических садов Урала и Поволжья , имеет статус научного учреждения и особо охраняемой природной территории . Основными научными направлениями работы являются : интродукция и акклиматизация растений , выведение и отбор новых форм и сортов , наиболее стойких и продуктивных в местных условиях . Ботанический сад расположен на двух участках общей площадью 2,7 га . Коллекции включают около 4000 видов , форм и сортов древесных , кустарниковых и травянистых растений , произрастающих в открытом и закрытом грунте . Из оранжерейных растений полнее всего представлены