Background & Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E

AUA2020 Annual Meeting OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E. Washington Convention Center | Washington, DC HOTEL NAME RATES HOTEL NAME RATES Marriott Marquis Washington, D.C. 3 Night Min. $355 Kimpton George Hotel* $359 Renaissance Washington DC Dwntwn Hotel 3 Night Min. $343 Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington DC* $379 Beacon Hotel and Corporate Quarters* $289 Kimpton Hotel Palomar Washington DC* $349 Cambria Suites Washington, D.C. Convention Center $319 Liaison Capitol Hill* $259 Canopy by Hilton Washington DC Embassy Row $369 Mandarin Oriental, Washington DC* $349 Canopy by Hilton Washington D.C. The Wharf* $279 Mason & Rook Hotel * $349 Capital Hilton* $343 Morrison - Clark Historic Hotel $349 Comfort Inn Convention - Resident Designated Hotel* $221 Moxy Washington, DC Downtown $309 Conrad Washington DC 3 Night Min $389 Park Hyatt Washington* $317 Courtyard Washington Downtown Convention Center $335 Phoenix Park Hotel* $324 Donovan Hotel* $349 Pod DC* $259 Eaton Hotel Washington DC* $359 Residence Inn Washington Capitol Hill/Navy Yard* $279 Embassy Suites by Hilton Washington DC Convention $348 Residence Inn Washington Downtown/Convention $345 Fairfield Inn & Suites Washington, DC/Downtown* $319 Residence Inn Downtown Resident Designated* $289 Fairmont Washington, DC* $319 Sofitel Lafayette Square Washington DC* $369 Grand Hyatt Washington 3 Night Min $355 The Darcy Washington DC* $296 Hamilton Hotel $319 The Embassy Row Hotel* $269 Hampton Inn Washington DC Convention 3 Night Min $319 The Fairfax at Embassy Row* $279 Henley Park Hotel 3 Night Min $349 The Madison, a Hilton Hotel* $339 Hilton Garden Inn Washington DC Downtown* $299 The Mayflower Hotel, Autograph Collection* $343 Hilton Garden Inn Washington/Georgetown* $299 The Melrose Hotel, Washington D.C.* $299 Hilton Washington DC National Mall* $315 The Ritz-Carlton Washington DC* $359 Holiday Inn Washington, DC - Capitol* $289 The St. -

National China Garden Foundation

MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT AMONG THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICER, THE NATIONAL CAPITAL PLANNING COMMISSION, AND THE NATIONAL CHINA GARDEN FOUNDATION REGARDING THE NATIONAL CHINA GARDEN AT THE U.S. NATIONAL ARBORETUM, WASHINGTON, D.C. This Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) is made as of this 18th day of November 2016, by and among the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the District of Columbia State Historic Preservation Officer (DCSHPO), the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), and the National China Garden Foundation (NCGF), (referred to collectively herein as the “Parties” or “Signatories” or individually as a “Party” or “Signatory”) pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), 16 U.S.C. §470f and its implementing regulations 36 CFR Part 800, and Section 110 of the NHPA, 16 U.S.C. § 470h-2. WHEREAS, the United States National Arboretum (USNA) is a research and education institution, public garden and living museum, whose mission is to enhance the economic, environmental, and aesthetic value of landscape plants through long-term, multidisciplinary research, conservation of genetic resources, and interpretative gardens and educational exhibits. Established in 1927, and opened to the public in 1959, the USNA is the only federally-funded arboretum in the United States and is open to the public free of charge; and, WHEREAS, the USNA, located at 3501 New York Avenue, NE, is owned by the United States government and under the administrative jurisdiction of the USDA’s ARS and occupies approximately 446 acres in Northeast Washington, DC and bound by Bladensburg Road on the west, New York Avenue on the north, and M Street on the south. -

Washington D.C

Calvin College Off Campus Programs Semester in Washington D.C. Important Numbers and Information Cell phone number for Professor Koopman: 616/328-4693 Address for Professor Koopman: 114 11th St., SE; Unit A Washington D.C. 20003 Washington Intern Housing Network (WIHN): 202/608-6276 Greystone House Address: 1243 New Jersey Avenue, N.W. Washington DC 20001 Maintenance emergency in House: 202/579-9446 (leave a message if no one picks up) Non-emergency in building (repairs, etc.): email notification to [email protected] Wifi access—information posted at the house inside the front door Quiet Hours: 9:00 pm to 7:00 am daily Internship Supervisor at your workplace: Name: _________________________________ Phone Number: __________________________ Ellen Hekman at Calvin College: 616/526-6565 Others: _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ CALVIN COLLEGE SEMESTER IN WASHINGTON DC Spring 2018 Introduction 1 Course Information Prerequisites 1 General Internships 1 Social Work Program 2 Preparation Clothing 2 Climate 4 Medical Issues 4 Semester Schedule 4 Housing Information Washington Intern Housing Network (WIHN) 4 WIHN Rules and Policies 6 Food and Meals 9 Travel Travel to Washington DC 10 Directions to Greystone House 10 Travel within Washington DC 12 Professor’s Housing and Contact Information 13 The City of Washington DC Directions and Maps 13 Visitor Information 13 Neighborhoods 13 Leaving the City 14 Cultural Information Group Outings 15 Cultural Opportunities and Site-seeing 15 Safety 17 Churches 18 Behavior and Health 21 Visitors 22 Attitude and Inclusiveness 22 communicate issues, problems and feelings. Furthermore, the entire group is responsible INTRODUCTION for each other during the semester. -

H/Benning Historic Architectural Survey

H Street/Benning Road Streetcar Project Historic Architectural Survey Prepared for: District Department of Transportation Prepared by: Jeanne Barnes HDR Engineering, Inc. 2600 Park Tower Drive Suite 100 Vienna, VA 22180 FINAL SUBMITTAL April 2013 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Project Background ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.1. Overhead Catenary System ................................................................................................... 2 1.1.2. Car Barn Training Center ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3. Traction Power Sub‐Stations ................................................................................................. 5 1.1.4. Interim Western Destination ................................................................................................ 6 1.2. Regulatory Context ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.1. DC Inventory of Historic Sites ............................................................................................... 7 1.2.2. National Register cof Histori Places ...................................................................................... 8 1.3. District of Columbia Preservation Process ................................................................................... -

7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Building in the Aftermath N AUGUST 29, HURRICANE KATRINA dialogue that can inform the processes by made landfall along the Gulf Coast of which professionals of all stripes will work Othe United States, and literally changed in unison to repair, restore, and, where the shape of our country. The change was not necessary, rebuild the communities and just geographical, but also economic, social, landscapes that have suffered unfathomable and emotional. As weeks have passed since destruction. the storm struck, and yet another fearsome I am sure that I speak for my hurricane, Rita, wreaked further damage colleagues in these cooperating agencies and on the same region, Americans have begun organizations when I say that we believe to come to terms with the human tragedy, good design and planning can not only lead and are now contemplating the daunting the affected region down the road to recov- question of what these events mean for the ery, but also help prevent—or at least miti- Chase W. Rynd future of communities both within the gate—similar catastrophes in the future. affected area and elsewhere. We hope to summon that legendary In the wake of the terrorist American ingenuity to overcome the physi- attacks on New York and Washington cal, political, and other hurdles that may in 2001, the National Building Museum stand in the way of meaningful recovery. initiated a series of public education pro- It seems self-evident to us that grams collectively titled Building in the the fundamental culture and urban char- Aftermath, conceived to help building and acter of New Orleans, one of the world’s design professionals, as well as the general great cities, must be preserved, revitalized, public, sort out the implications of those and protected. -

Dc Homeowners' Property Taxes Remain Lowest in The

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org February 27, 2009 DC HOMEOWNERS’ PROPERTY TAXES REMAIN LOWEST IN THE REGION By Katie Kerstetter This week, District homeowners will receive their assessments for 2010 and their property tax bills for 2009. The new assessments are expected to decline modestly, after increasing significantly over the past several years. The new assessments won’t impact homeowners’ tax bills until next year, because this year’s bills are based on last year’s assessments. Yet even though 2009’s tax bills are based on a period when average assessments were rising, this analysis shows that property tax bills have decreased or risen only moderately for many homeowners in recent years. DC homeowners continue to enjoy the lowest average property tax bills in the region, largely due to property tax relief policies implemented in recent years. These policies include a Homestead Deduction1 increase from $30,000 to $67,500; a 10 percent cap on annual increases in taxable assessments; and an 11-cent property tax rate cut. The District also adopted a “calculated rate” provision that decreases the tax rate if property tax collections reach a certain target. As a result of these measures, most DC homeowners have seen their tax bills fall — or increase only modestly — over the past four years. In 2008, DC homeowners paid lower property taxes on average than homeowners in surrounding counties. Among homes with an average sales price of $500,000, DC homeowners paid an average tax of $2,725, compared to $3,504 in Montgomery County, $4,752 in PG County, and over $4,400 in Arlington and Fairfax counties. -

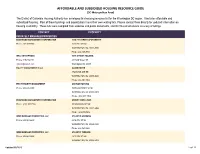

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

Shuttle Services at Metro Facilities August 2011

Shuttle Services at Metro Facilities August 2011 Shuttle Services at Metro Facilities Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Office of Bus Planning August 2011 Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Office of Bus Planning Jim Hamre, Director of Bus Planning Krys Ochia, Branch Manager 600 5th Street NW Washington, DC 20001 Parsons Brinckerhoff Brian Laverty, AICP, Project Manager Nicholas Schmidt, Task Manager 1401 K Street NW, Suite 701 Washington, DC 20005 Contents Executive Summary ES-1 Existing Conditions ES-1 Policies and Procedures ES-2 Future Demand ES-3 Recommendations ES-4 Introduction 1 Study Process 3 Coordination 3 On-Site Observations 3 Operating Issues 3 Future Demand 4 Permitting and Enforcement 4 Existing Conditions 7 Key Observations 8 Operating Issues 9 Policies and Procedures 17 Permitting 17 Enforcement 19 Future Demand 25 Methodology 25 Results 28 Recommendations 33 Facility Design 34 Demand Management 37 Permitting 39 Enforcement 42 Contents | i Figures Figure ES-1: Future Shuttle Demand Estimate ES-4 Figure 1: Location of Peer U.S. Transit Agencies 4 Figure 2: Study Stations 7 Figure 3: Vehicles in Tight Turning Areas May Block Bus Bay Entrances (New Carrollton Station) 11 Figure 4: Long Kiss & Ride Queue (New Carrollton Station) 11 Figure 5: Pedestrian Shortcut (Southern Avenue Station) 11 Figure 6: Shuttle Blocking Kiss & Ride Travel Lane (King Street Station) 12 Figure 7: Shuttle Blocking Bus Stop (Anacostia Station) 13 Figure 8: Typical Signs Prohibiting Non-Authorized Access to Station Bus Bays -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Housing in the Nation's Capital

Housing in the Nation’s2005 Capital Foreword . 2 About the Authors. 4 Acknowledgments. 4 Executive Summary . 5 Introduction. 12 Chapter 1 City Revitalization and Regional Context . 15 Chapter 2 Contrasts Across the District’s Neighborhoods . 20 Chapter 3 Homeownership Out of Reach. 29 Chapter 4 Narrowing Rental Options. 35 Chapter 5 Closing the Gap . 43 Endnotes . 53 References . 56 Appendices . 57 Prepared for the Fannie Mae Foundation by the Urban Institute Margery Austin Turner G. Thomas Kingsley Kathryn L. S. Pettit Jessica Cigna Michael Eiseman HOUSING IN THE NATION’S CAPITAL 2005 Foreword Last year’s Housing in the Nation’s Capital These trends provide cause for celebration. adopted a regional perspective to illuminate the The District stands at the center of what is housing affordability challenges confronting arguably the nation’s strongest regional econ- Washington, D.C. The report showed that the omy, and the city’s housing market is sizzling. region’s strong but geographically unbalanced But these facts mask a much more somber growth is fueling sprawl, degrading the envi- reality, one of mounting hardship and declining ronment, and — most ominously — straining opportunity for many District families. Home the capacity of working families to find homes price escalation is squeezing families — espe- they can afford. The report provided a portrait cially minority and working families — out of of a region under stress, struggling against the city’s housing market. Between 2000 and forces with the potential to do real harm to 2003, the share of minority home buyers in the the quality of life throughout the Washington District fell from 43 percent to 37 percent. -

Directions to the University of Maryland

DIRECTIONS TO THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND TRAVEL BY AUTOMOBILE From Baltimore and Points North From Annapolis and Points East • Take I-95 South to Washington, D.C.'s Capital • Take U.S. 50 to Washington, D.C.'s Capital Beltway (I-495). Beltway (I-495). • Take Exit 27 and then Follow signs to Exit 25 (U.S. • Go North on I-95/I-495 toward Baltimore. 1 South toward College Park). • Take Exit 25 (U.S. 1 South toward College • Proceed approximately two miles south on U.S. Park). Route 1. • Proceed approximately two miles south on • Turn right onto Campus Drive. U.S. Route 1. • Turn right onto Campus Drive. From Virginia and Points South • Take I-95 North to Washington, D.C.'s Capital From Washington, D.C. (Northwest/Southwest) Beltway (I-495). • Take 16th St. North which becomes • Continue North on I-95/I-495 toward Baltimore. Georgia Ave. North at Maryland/D.C. line. • Take Exit 25 (U.S. 1 South toward College • Go East on I-495 toward Baltimore. Park).Proceed approximately two miles south on • Take Exit 25 (U.S. 1 South toward College U.S. Route 1. Park). • Turn right onto Campus Drive. • Proceed approximately two miles south on U.S. Route 1. From Virginia and Points West • Turn right onto Campus Drive. • Take I-66 East or I-270 South to Washington, D.C.'s Capital Beltway (I-495). From Washington, D.C. (Northeast/Southeast) • Go East on I-495 toward Baltimore/Silver Spring. • Take Rhode Island Ave. (U.S. 1 North) • Take Exit 25 (U.S.