Cummins Site: a Late Palaeo-Indian (Plano) Site at Thunder Bay, Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calgary Montreal Thunder Bay Halifax Saskatoon

working together to create a national movement to strengthen “We all have a blueprint for life…and YOUTHSCAPE IS SUPPORTED BY youth engagement and build resilient communities. if we were just to show each other THE J. W. MCCONNELL FAMILY FOUNDATION AS PART OF A our plans…then maybe the bigger plan embracing bold visions for change! YOUTH ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY can start to change…to adapt to all TO FOSTER INNOVATIVE CHANGE YouthScape is based on the idea that young people can make important our needs…but we must first come AND BUILD RESILIENT contributions to building resilient communities and systems that are inclusive, together…this is the first step.” COMMUNITIES AT BOTH THE adaptable and healthy. Our society does not always support and recognize these LOCAL AND NATIONAL LEVEL. GABRIELLE FELIX & TALA TOOTOOSIS contributions, especially when youth are ‘diverse’, excluded and marginalized YOUTHSCAPE COORDINATORS THE INITIATIVE IS COORDINATED SASKATOON culturally or economically. By encouraging young people to develop their talents, BY THE INTERNATIONAL learn new skills and to become engaged in our communities, INSTITUTE FOR CHILD RIGHTS we can support positive change and make our communities AND DEVELOPMENT (IICRD), community : Thunder Bay, Ontario Thunder Bay stronger. YouthScape is an exciting Canada-wide initiative to AN ORGANIZATION THAT convening organization : United Way Thunder Bay : www.unitedway-tbay.on.ca engage all young people in creating change. building on collective strengths – SUPPORTS CROSS-COMMUNITY LEARNING AND RESEARCH, In this first phase, five YouthScape communities across Canada generating positive change INCREASES LOCAL CAPACITY AND have been selected to develop exciting new projects to create . -

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

www.thunderbay.noaa.gov (989) 356-8805 Alpena, MI49707 500 WestFletcherStreet Heritage Center Great LakesMaritime Contact Information N T ATIONAL ATIONAL HUNDER 83°30'W 83°15'W 83°00'W New Presque Isle Lighthouse Park M North Bay ARINE Wreck 82°45'W Old Presque Isle Lighthouse Park B S ANCTUARY North Albany Point Cornelia B. AY Windiate Albany • Types ofVesselsLostatThunderBay South Albany Point Sail Powered • • • Scows Ships, Brigs, Schooners Barks Lake Esau Grand Norman Island Wreck Point Presque Isle Lotus Lake Typo Lake of the Florida • Woods Steam Powered Brown • • Island Sidewheelers Propellers John J. Grand Audubon LAKE Lake iver R ll e B HURON Whiskey False Presque Isle Point • Other • • Unpowered Combustion Motor Powered 45°15'N 45°15'N Bell Czar Bolton Point Besser State Besser Bell Natural Area Wreck Defiance (by quantityoflossforallwrecks) Cargoes LostatThunderBay • • • • Iron ore Grain Coal Lumber products Ferron Point Mackinaw State Forest Dump Scow Rockport • • • • 23 Middle Island Sinkhole Fish Salt Package freight Stone Long Portsmouth Lake Middle Island Middle Island Lighthouse Middle Lake • • • Copper ore Passengers Steel Monaghan Point New Orleans 220 Long Lake Creek Morris D.M. Wilson Bay William A. Young South Ninemile Point Explore theThunderBayNationalMarineSanctuary Fall Creek Salvage Barge &Bathymetry Topography Lincoln Bay Nordmeer Contours inmeters Grass Lake Mackinaw State Forest Huron Bay 0 Maid of the Mist Roberts Cove N Stoneycroft Point or we gi an El Cajon Bay Ogarita t 23 Cre Fourmile Mackinaw State -

Fast Forward Thunder

Community Report 2001-2003 Mayor Lynn Peterson, Co-Chair Ray Riley, Co-Chair As the new Co-Chair of Fast Fast Forward is the community’s Inside: Forward, it is my privilege to intro- vision for the future and it is the voice duce this report to the community of the citizens of Thunder Bay. It was created through a public consultation Quality of Life 2 and to acknowledge the work of the former co-chair, Ken Boshcoff, dur- initiative in the late ‘90s and the out- ing the years it chronicles. We are come was a planning framework com- Our Community Partners 2 pleased to know we can count on plete with strategic directions, goals Ken’s continued support. and objectives. The role of the Fast Forward partner- Celebrating our As I said in my inaugural address to Successes 3 City Council last month, the building ship and steering committee is: blocks are in place like never before • to bring together community groups for a concrete action plan to benefit sharing common interests. Direction Thunder Bay 4 our community. We have: • to share information with and among • Fast Forward, the community devel- various interest groups. opment plan, which has been endorsed by more than 70 community • to report annually to the citizens on organizations. It provides us with a vision and a general blueprint. the community’s progress in achieving Fast Forward’s goals and objec- • the priorities honed by community leaders at the September tives, a sort of "How are we doing?" Economic Summit. • to fine-tune and adjust the planning framework to stay abreast of • an expanding community pride that comes from a series of remarkable the community’s changing needs. -

The Lake Superior Aquatic Invasive Species Guide Prepared By: Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters March 2014

The Lake Superior Aquatic Invasive Species Guide Prepared by: Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters March 2014 Acknowledgements: This guide was made possible and is relevant in Canada and the United States thanks to the Lake Superior Binational Program, and the Great Lakes Panel on Aquatic Nuisance Species. Funding and initial technical review for this guide was provided by the Government of Canada, through Environment Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, respectively. Oversight and technical reviews were provided by the Province of Ontario, through the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and the Great Lakes Panel on Aquatic Nuisance Species. The University of Minnesota Sea Grant Program provided oversight, review, and through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative helped provide funding for the first print run. This guide was patterned after The Lake Champlain Basin Aquatic Invasive Species Guide, developed by the Lake Champlain Basin Program Aquatic Nuisance Species Subcommittee - Spread Prevention Workgroup. We sincerely thank them for allowing us to use their guide. Suggested Citation: Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters. 2014. The Lake Superior Aquatic Invasive Species Guide. Prepared in collaboration with the Lake Superior Binational Program and the Great Lakes Panel on Aquatic Nuisance Species. Available at www.Invadingspecies.com. Cover photo of Round Goby by David Copplestone-OFAH Lake Superior Watershed Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................page 2 Guide to Aquatic Invasive Fishes -

Facilities Approved to Export Pelletized Screenings NOTICE This List Changes Frequently

Facilities Approved to Export Pelletized Screenings NOTICE This list changes frequently. Contact the Seed Examination Facility (SEF) for possible updates to the list. [email protected] Phone: 301-313-9332 [email protected] Phone: 301-313-9329 The following facilities are approved to export pelletized screenings to the U.S. using Export Certificate Under CFIA Directive D-11-04. 1. Alliance Grain Terminal 1155 Stewart St. Vancouver, BC V6A 4H4, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-01 2. Cargill North Vancouver Terminal 801 Low Level Road North Vancouver, BC V7L 4J5, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-02 3. Cascadia Terminal 3333 New Brighton Road Vancouver, BC V5K 5J7, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-03 4. Pacific Terminal 1803 Stewart Street Vancouver, BC V5L 5G1, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-04 5. Rowland Seeds Inc. 421 1st Avenue South Vauxhall, AB T0K 2K0, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-06 6. Superior Elevator 140 Darrel Ave. Thunder Bay, ON P7B 6T8, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-07 02/2021 1 7. Viterra Inc. 609 Maureen Street Thunder Bay, ON P7B 6T2, Canada CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-05 8. G3 Terminal Vancouver 95 Brooksbank Avenue North Vancouver, BC V7J2B9 CFIA Facility Approval Number: CFIA-GSP-08 2 02/2021 Export Certificate Under CFIA Directive D-11-04 Export Certificate Under CFIA Directive D-11-04 Shipment Identification Number ______________ Facility Name Facility Address CFIA Facility Approval Number CFIA - GSP - ** Bin Number This certificate attests thatat the gragrainin screening ppellets in this consignment are not intendedntendednded to be used for planting, and; 1) Meet the processingrocessingcessing rerequirquirementuiremements as outlined in the compliancence agreemenagreementt betweebetween the above facility and the CFIAA ass per Directive D-1D-11-04. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Starting a Business Guide

Starting a Business Guide 2 Starting a Business Guide Prepared by: Tourism & Economic Development’s Thunder Bay & District Entrepreneur Centre P.O. Box 800, 111 Syndicate Avenue South Victoriaville Civic Centre, 2nd Floor Thunder Bay, Ontario P7C 5K4 Contact: Lucas Jewitt Development Officer Entrepreneur Centre Telephone: (807) 625-3972 Toll Free: 1-800-668-9360 Fax: (807) 623-3962 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ThunderBay.ca 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Are you an Entrepreneur? Introduction 4 Finding a Business Idea Chapter One 5 The Feasibility Analysis Chapter Two 7 The Business Plan Chapter Three 11 Financing Chapter Four 15 Legal/Regulatory Information Chapter Five 28 City/Municipal Policies and Regulations 28 Provincial Policies and Regulations 34 Federal Policies and Regulations 45 Other Administrative Questions 46 Agency and Organizational Contacts to Assist with Your Start-up Chapter Six 50 Local Agencies and Organizations (Thunder Bay) 50 Provincial Agencies and Organizations 57 Federal/National Agencies and Organizations 57 Quick Reference Telephone List for Thunder Bay 61 Quick Reference Telephone List for Unorganized Townships 62 Organizational and Informational Websites 63 4 INTRODUCTION: ARE YOU AN ENTREPRENEUR? Starting a business can be very rewarding, but also time- consuming and labour-intensive. Before you start researching, obtaining sources of funding, finding a location and completing all of the other tasks necessary to open a business, you’ll probably want to know if you possess the typical characteristics of successful entrepreneurs. Of course, there are many variables in determining entrepreneurial success, but knowing that you fit the profile is an important first step (as well as a confidence booster!) in getting your business off the ground. -

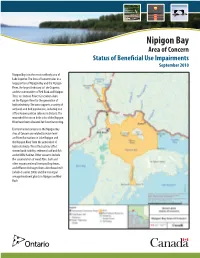

Nipigon Bay Area of Concern Status of Beneficial Use Impairments September 2010

Nipigon Bay Area of Concern Status of Beneficial Use Impairments September 2010 Nipigon Bay is in the most northerly area of Lake Superior. The Area of Concern takes in a large portion of Nipigon Bay and the Nipigon River, the largest tributary to Lake Superior, and the communities of Red Rock and Nipigon. There are Ontario Power Generation dams on the Nipigon River for the generation of hydroelectricity. The area supports a variety of wetlands and bird populations, including one of four known pelican colonies in Ontario. The watershed forests on both sides of the Nipigon River have been allocated for forest harvesting. Environmental concerns in the Nipigon Bay Area of Concern are related to water level and flow fluctuations in Lake Nipigon and the Nipigon River from the generation of hydroelectricity. These fluctuations affect stream bank stability, sediment load and fish and wildlife habitat. Other concerns include the accumulation of wood fibre, bark and other organic material from past log drives, and effluent discharges from a linerboard mill (which closed in 2006) and the municipal sewage treatment plants in Nipigon and Red Rock. PARTNERSHIPS IN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Nipigon Bay was designated an Area of Concern in 1987 under the Canada–United States Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Areas of Concern are sites on the Great Lakes system where environmental quality is significantly degraded and beneficial uses are impaired. Currently, there are 9 such designated areas on the Canadian side of the Great Lakes, 25 in the United States, and 5 that are shared by both countries. In each Area of Concern, government, community and industry partners are undertaking a coordinated effort to restore environmental quality and beneficial uses through a remedial action plan. -

More Than Just a Lake! TOPIC Great Lake Drainage Basins AUDIENCE Grades 1-6; 10-30 Students

More Than Just a Lake! TOPIC Great Lake drainage basins AUDIENCE Grades 1-6; 10-30 students SETTING By creating a map of the rivers flowing into your Great Lake, Large, open indoor space is learn how rivers form a watershed. required GOAL To understand the concept of a drainage basin or watershed, and how that concept relates to the BACKGROUND around the lake as gravity pulls water local Great Lake watershed. All lakes and rivers have a set area to the lowest point. Water draining of land that water drains into them to the lowest common point is the OBJECTIVES • Students will understand the from, called the “watershed” or simplest definition of a watershed. defining role that rivers have “drainage basin.” Drainage basins are in watershed activity important environmentally because 2. Introduction to the model • Students will be able to state whether they live inside or whatever happens within the basin of watershed outside the drainage basin of the lake can happen to the lake itself. Students gather around the “shore” their Great Lake Toxic substances spilled or placed of the lake. Explain that the blue • Older students will be able to identify the river drainage on the land or in watershed rivers yarn represents rivers. With younger basin in which they live can end up in the lake. See the Great students, demonstrate how one river Lakes Watershed Fact Sheets for ad- might look on the map as it flows MATERIALS ditional information about your local into your Great Lake. • Large floor map of your Great Lake (or an outline on the watershed. -

N Shore L. Superior: Geology, Scenery

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Petition to List US Populations of Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser Fulvescens)

Petition to List U.S. Populations of Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) as Endangered or Threatened under the Endangered Species Act May 14, 2018 NOTICE OF PETITION Submitted to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on May 14, 2018: Gary Frazer, USFWS Assistant Director, [email protected] Charles Traxler, Assistant Regional Director, Region 3, [email protected] Georgia Parham, Endangered Species, Region 3, [email protected] Mike Oetker, Deputy Regional Director, Region 4, [email protected] Allan Brown, Assistant Regional Director, Region 4, [email protected] Wendi Weber, Regional Director, Region 5, [email protected] Deborah Rocque, Deputy Regional Director, Region 5, [email protected] Noreen Walsh, Regional Director, Region 6, [email protected] Matt Hogan, Deputy Regional Director, Region 6, [email protected] Petitioner Center for Biological Diversity formally requests that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”) list the lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in the United States as a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544. Alternatively, the Center requests that the USFWS define and list distinct population segments of lake sturgeon in the U.S. as threatened or endangered. Lake sturgeon populations in Minnesota, Lake Superior, Missouri River, Ohio River, Arkansas-White River and lower Mississippi River may warrant endangered status. Lake sturgeon populations in Lake Michigan and the upper Mississippi River basin may warrant threatened status. Lake sturgeon in the central and eastern Great Lakes (Lake Huron, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River basin) seem to be part of a larger population that is more widespread. -

Rivers at Risk: the Status of Environmental Flows in Canada

Rivers at Risk: The Status of Environmental Flows in Canada Prepared by: Becky Swainson, MA Research Consultant Prepared for: WWF-Canada Freshwater Program Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the river advocates and professionals from across Canada who lent their time and insights to this assessment. Also, special thanks to Brian Richter, Oliver Brandes, Tim Morris, David Schindler, Tom Le Quesne and Allan Locke for their thoughtful reviews. i Rivers at Risk Acronyms BC British Columbia CBM Coalbed methane CEMA Cumulative Effects Management Association COSEWIC Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada CRI Canadian Rivers Institute DFO Fisheries and Oceans Canada EBF Ecosystem base flow IBA Important Bird Area IFN Instream flow needs IJC International Joint Commission IPP Independent Power Producer GRCA Grand River Conservation Authority LWR Low Water Response MOE Ministry of Environment (Ontario) MNR Ministry of Natural Resources (Ontario) MRBB Mackenzie River Basin Board MW Megawatt NB New Brunswick NGO Non-governmental organization NWT Northwest Territories P2FC Phase 2 Framework Committee PTTW Permit to Take Water QC Quebec RAP Remedial Action Plan SSRB South Saskatchewan River Basin UNESCO United Nations Environmental, Scientific and Cultural Organization US United States WCO Water Conservation Objectives ii Rivers at Risk Contents Rivers at Risk: The Status of Environmental Flows in Canada CONTENTS Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................