Memories and Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intimations Surnames

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames H-K This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames H-K Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage HAASE / LEGRING 1858 Frederick Auguste Haase, chief steward SS Bremen, to Ottile Wilhelmina Louise Amelia Legring, daughter of Reverend Charles Legring, Bremen, at Greenock on 24th May 1858 by Reverend J. Nelson. (Greenock Advertiser 25.5.1858) Marriage HAASE / OHLMS 1894 William Ohlms, hairdresser, 7 West Blackhall Street, to Emma, 4th daughter of August Haase, Herrnhut, Saxony, at Glengarden, Greenock on 6th June 1894 .(Greenock Telegraph 7.6.1894) Death HACKETT 1904 Arthur Arthur Hackett, shipyard worker, husband of Mary Jane, died at Greenock Infirmary in June 1904. (Greenock Telegraph 13.6.1904) Death HACKING 1878 Samuel Samuel Craig, son of John Hacking, died at 9 Mill Street, Greenock on 9th January 1878. -

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

Cathode Rays 89 Cathode Rays

Cathode Rays 89 Cathode Rays Theodore Arabatzis C The detection of cathode rays was a by-product of the investigation of the discharge of electricity through rarefied gases. The latter phenomenon had been studied since the early eighteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century it was known that the passage of electricity through a partly evacuated tube produced a glow in the gas, whose color depended on its chemical composition and its pressure. Below a certain pressure the glow assumed a stratified pattern of bright and dark bands. During the second half of the nineteenth century the discharge of electricity through gases became a topic of intense exploratory experimentation, primarily in Germany [21]. In 1855 the German instrument maker Heinrich Geißler (1815– 1879) manufactured improved vacuum tubes, which made possible the isolation and investigation of cathode rays [23]. In 1857 Geissler’s tubes were employed by Julius Pl¨ucker (1801–1868) to study the influence of a magnet on the electrical dis- charge. He observed various complex and striking phenomena associated with the discharge. Among those phenomena were a “light which appears about the negative electrode” and a fluorescence in the glass of the tube ([9], pp. 122, 130). The understanding of those phenomena was advanced by Pl¨ucker’s student and collaborator, Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (1824–1914), who observed that “if any ob- ject is interposed in the space filled with glow-light [emanating from the negative electrode], it throws a sharp shadow on the fluorescent side” ([5], p. 117). This effect implied that the “rays” emanating from the cathode followed a straight path. -

Rutherford's Nuclear World: the Story of the Discovery of the Nuc

Rutherford's Nuclear World: The Story of the Discovery of the Nuc... http://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/rutherford/sections/atop-physic... HOME SECTIONS CREDITS EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT US rutherford's explore the atom learn more more history of learn about aip's nuclear world with rutherford about this site physics exhibits history programs Atop the Physics Wave ShareShareShareShareShareMore 9 RUTHERFORD BACK IN CAMBRIDGE, 1919–1937 Sections ← Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next → In 1962, John Cockcroft (1897–1967) reflected back on the “Miraculous Year” ( Annus mirabilis ) of 1932 in the Cavendish Laboratory: “One month it was the neutron, another month the transmutation of the light elements; in another the creation of radiation of matter in the form of pairs of positive and negative electrons was made visible to us by Professor Blackett's cloud chamber, with its tracks curled some to the left and some to the right by powerful magnetic fields.” Rutherford reigned over the Cavendish Lab from 1919 until his death in 1937. The Cavendish Lab in the 1920s and 30s is often cited as the beginning of modern “big science.” Dozens of researchers worked in teams on interrelated problems. Yet much of the work there used simple, inexpensive devices — the sort of thing Rutherford is famous for. And the lab had many competitors: in Paris, Berlin, and even in the U.S. Rutherford became Cavendish Professor and director of the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919, following the It is tempting to simplify a complicated story. Rutherford directed the Cavendish Lab footsteps of J.J. Thomson. Rutherford died in 1937, having led a first wave of discovery of the atom. -

The Royal Society Medals and Awards

The Royal Society Medals and Awards Table of contents Overview and timeline – Page 1 Eligibility – Page 2 Medals open for nominations – Page 8 Nomination process – Page 9 Guidance notes for submitting nominations – Page 10 Enquiries – Page 20 Overview The Royal Society has a broad range of medals including the Premier Awards, subject specific awards and medals celebrating the communication and promotion of science. All of these are awarded to recognise and celebrate excellence in science. The following document provides guidance on the timeline and eligibility criteria for the awards, the nomination process and our online nomination system Flexi-Grant. Timeline • Call for nominations opens 30 November 2020 • Call for nominations closes on 15 February 2021 • Royal Society contacts suggested referees from February to March if required. • Premier Awards, Physical and Biological Committees shortlist and seek independent referees from March to May • All other Committees score and recommend winners to the Premier Awards Committee by April • Premier Awards, Physical and Biological Committees score shortlisted nominations, review recommended winners from other Committees and recommend final winners of all awards by June • Council reviews and approves winners from Committees in July • Winners announced by August Eligibility Full details of eligibility can be found in the table. Nominees cannot be members of the Royal Society Council, Premier Awards Committee, or selection Committees overseeing the medal in question. More information about the selection committees for individual medals can be found in the table below. If the award is externally funded, nominees cannot be employed by the organisation funding the medal. Self-nominations are not accepted. -

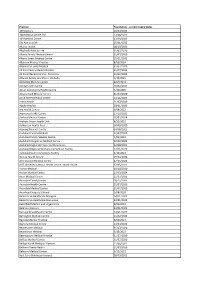

HPI Facility ID Foundation Certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date

HPI Facility ID Foundation certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date F2K013-C 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 F3M373-E Albahadly Medical Limited 31/07/2020 F3K590-C Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 F2G001-C Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F2R087-G Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 F3K709-B Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 F33087-C Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 F0K028-D Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 F35061-F Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 F2R068-C Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 F2M082-K Beerescourt Medical Practice 31/07/2020 F2M080-F Belfast Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F35020-C Bellomo Family Health 31/07/2020 F2P029-E Bester McKay Family Doctors Ltd 31/07/2020 F0T083-H Birkdale Family Doctors 31/07/2020 F2H027-D Bishopdale Medical Clinic 22/08/2020 F2Q009-D Bluff Community Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F3L990-B Botany Medical and Urgent Care 31/07/2020 F0L035-F Broadway Medical Centre Dunedin 31/07/2020 F2E049-K Bryndwr Medical Rooms 31/07/2020 F2Q011-B Burnside Medical Centre 3/03/2023 F2R082-H Casebrook Surgery 31/07/2020 F2F049-D Cashmere Health 31/07/2020 F2M056-J Cashmere Medical Practice 23/03/2023 F2G011-F Catlins Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0W020-K Centennial Health 31/07/2020 F2J008-E Central Family Health Care 28/11/2020 F2R022-A Central Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F1M048-D Central Medical Centre - New Plymouth 3/12/2022 F2M083-A Chartwell Health Ltd 19/01/2023 F39013-D City West Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0T019-K CityMed 2/12/2022 F2K010-H Clarence Medical Centre 26/12/2022 F0U074-A Clevedon -

Doctorat Honoris Causa

DOCTORAT HONORIS CAUSA Acord núm. 204/2007 del Consell de Govern, pel qual s’aprova la concessió del doctorat Honoris Causa al Professor Sir Michael Atiyah. Document aprovat per la Comissió Permanent del dia 3/12/2007. Document aprovat pel Consell de Govern del dia 17/12/2007. DOCUMENT CG 14/12 2007 Secretaria General Desembre de 2007 PROPOSTA D’ACORD DEL CONSELL DE GOVERN PER A CONCEDIR EL DOCTORAT HONORIS CAUSA PER LA UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE CATALUNYA, AL PROFESSOR SIR MICHAEL ATIYAH ANTECEDENTS: 1. El professor Sir Michael Atiyah ha estat guardonat, entre d’altres distincions, amb la Medalla Fields (1966), atorgada per la Unió Matemàtica Internacional, i el Premi Abel (2004), atorgat per l’Acadèmia de Ciències de Noruega, ambdues reconegudes com un Premi Nobel de les Matemàtiques. També ha estat un dels impulsors més decisius de la Societat Matemàtica Europea. 2. En relació amb Catalunya i Barcelona, i més concretament, amb la UPC, el professor Sir Michael Atiyah ha estat president del Comitè Científic del 3r Congrés Europeu de Matemàtiques celebrat a Barcelona l’any 2000. 3. El prestigi internacional del professor Sir Michael Atiyah el fa un candidat idoni com a primer doctor honoris causa per la UPC en un àrea en la qual la nostra Universitat compta amb una comunitat nombrosa i amb un gran prestigi i reconeixement internacionals. 4. El rector ha rebut una proposta formal per a investir el professor Sir Michael Atiyah com a doctor honoris causa per la Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, signada pel degà de la Facultat de Matemàtiques i Estadística, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada I, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada II, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada III, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada IV, i el director del departament d’Estadística i Investigació Operativa. -

Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997) by Alan Hayward NCUACS catalogue no. 95/8/00 R.V. Jones 1 NCUACS 95/8/00 Title: Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997), physicist Compiled by: Alan Hayward Description level: Fonds Date of material: 1928-1998 Extent of material: 230 boxes, ca 5000 items Deposited in: Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge CB3 0DS Reference code: GB 0014 2000 National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, University of Bath. NCUACS catalogue no. 95/8/00 R.V. Jones 2 NCUACS 95/8/00 The work of the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, and the production of this catalogue, are made possible by the support of the Research Support Libraries Programme. R.V. Jones 3 NCUACS 95/8/00 NOT ALL THE MATERIAL IN THIS COLLECTION MAY YET BE AVAILABLE FOR CONSULTATION. ENQUIRIES SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IN THE FIRST INSTANCE TO: THE KEEPER OF THE ARCHIVES CHURCHILL ARCHIVES CENTRE CHURCHILL COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE R.V. Jones 4 NCUACS 95/8/00 LIST OF CONTENTS Items Page GENERAL INTRODUCTION 6 SECTION A BIOGRAPHICAL A.1 - A.302 12 SECTION B SECOND WORLD WAR B.1 - B.613 36 SECTION C UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN C.1 - C.282 95 SECTION D RESEARCH TOPICS AND SCIENCE INTERESTS D.1 - D.456 127 SECTION E DEFENCE AND INTELLIGENCE E.1 - E.256 180 SECTION F SCIENCE-RELATED INTERESTS F.1 - F.275 203 SECTION G VISITS AND CONFERENCES G.1 - G.448 238 SECTION H SOCIETIES AND ORGANISATIONS H.1 - H.922 284 SECTION J PUBLICATIONS J.1 - J.824 383 SECTION K LECTURES, SPEECHES AND BROADCASTS K.1 - K.495 450 SECTION L CORRESPONDENCE L.1 - L.140 495 R.V. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

CHIST1 Joseph Barcroft.Pmd

Anales de la Facultad de MedicinaJoseph Barcroft y la expedición anglo-americana a los Andes Peruanos ISSN 1025 - 5583 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Págs. 159-173 Historia Joseph Barcroft y la expedición anglo-americana a los Andes Peruanos (1921-1922) Oscar G. Pamo 1,2 Resumen Joseph Barcroft (1872-1947), fisiólogo británico de Cambridge, vino al Perú hacia fines de 1921 liderando la expedición angloamericana para estudiar las características fisiológicas que permiten a los humanos aclimatarse a la vida en las grandes alturas. Arribaron a Cerro de Pasco, realizando diversas mediciones y a diferentes altitudes, en ellos, en el personal norteamericano de la mina y en algunos nativos. Esta experiencia, publicada dos años más tarde, generaría en el doctor Carlos Monge Medrano (1884-1970) y otros investigadores nacionales el interés de conocer la biología y la patología del hombre andino, en 1927. Palabras clave Historia de la medicina, Perú; altitud; ecosistema andino; Barcroft, Joseph. Joseph Barcroft and the Anglo-American lideró la expedición angloamericana que a fines de 1921 expedition to the Peruvian Andes (1921-1922) vino a los Andes peruanos a estudiar la fisiología Abstract respiratoria del humano sometido a baja presión Joseph Barcroft (1872-1947), British Cambridge atmosférica. Sus conclusiones, que publicó dos años physiologist, came to Peru at the end of 1921 leading the después, dieron lugar a una respuesta del Dr. Carlos Monge Anglo-American expedition in order to study the Medrano en 1927. De allí en adelante, se realizó numerosas physiological characteristics that let human beings investigaciones para estudiar la salud y la enfermedad del acclimatize to live at high altitude environments. -

571 Write Up.Pdf

This paper comprises a brief history of the origins and early development of radar meteorology. Therefore, it will cover the time period from a few years before World War II through about the 1970s. The earliest developments of radar meteorology occurred in England, the United States, and Canada. Among these three nations, however, most of the first discoveries and developments were made in England. With the exception of a few minor details, it is there where the story begins. Even as early as 1900, Nicola Tesla wrote of the potential for using waves of a frequency from the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum to detect distant objects. Then, on 11 December 1924, E. V. Appleton and M.A.F. Barnett, two Englishmen, used a radio technique to determine the height of the ionosphere using continuous wave (CW) radio energy. This was the first recorded measurement of the height of the ionosphere using such a method, and it got Appleton a Nobel Prize. However, it was Merle A. Tuve and Gregory Breit (the former of Johns Hopkins University, the latter of the Carnegie Institution), both Americans, who six months later – in July 1925 – did the same thing using pulsed radio energy. This was a simpler and more direct way of doing it. As the 1930s rolled on, the British sensed that the next world war was coming. They also knew they would be forced to defend themselves against the German onslaught. Knowing they would be outmanned and outgunned, they began to search for solutions of a technological variety. This is where Robert Alexander Watson Watt – a Scottish physicist and then superintendent of the Radio Department at the National Physical Laboratory in England – came into the story. -

Foundation- Current Expiry Dates.Xlsx

Practice Foundation ‐ current expiry dates 109 Doctors 10/03/2023 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 169 Medical Centre 13/09/2023 5th Ave on 10th 25/01/2022 Akaroa Health 18/10/2021 Albahadly Medical Ltd 31/07/2020 Albany Family Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Albany Street Medical Centre 15/01/2021 Alberton Medical Practice 8/02/2024 Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 All Care Family Medical Centre 21/07/2023 All Care Medical Centre ‐ Ponsonby 31/07/2023 Alliance Family Healthcare‐Otahuhu 5/10/2021 Amberley Medical Centre 8/02/2024 Amity Health Centre 10/02/2021 Amuri Community Health Centre 4/10/2020 Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Anne Street Medical Centre 24/11/2023 Aotea Health 31/07/2020 Apollo Medical 28/01/2023 Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 Aramoho Health Centre 17/10/2021 Archers Medical Centre 20/02/2024 Arohata Prison Health Unit 6/12/2022 Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 Aspiring Medical Centre 24/08/2021 Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 Auckland Regional Prison Health Services 22/08/2023 Auckland Regional Womens Corrections Facility 17/11/2023 Auckland South Corrections Facility 5/10/2021 Aurora Health Centre 19/04/2022 AUT Student Medical Centre 27/05/2022 AUT Wellesley Campus Health Centre ‐ North Shore 27/05/2022 Avalon Medical 18/10/2020 Avalon Medical Centre 25/03/2024 Avon Medical Centre 11/07/2021 Avondale Family Doctor 18/12/2023 Avondale Health Centre 31/07/2020 Avondale Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020