Should Animals Have a Right to Work? Promises and Pitfalls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foucault and Animals

Foucault and Animals Edited by Matthew Chrulew, Curtin University Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel, The University of Sydney LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Foreword vii List of Contributors viii Editors’ Introduction: Foucault and Animals 1 Matthew Chrulew and Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel PART 1 Discourse and Madness 1 Terminal Truths: Foucault’s Animals and the Mask of the Beast 19 Joseph Pugliese 2 Chinese Dogs and French Scapegoats: An Essay in Zoonomastics 37 Claire Huot 3 Violence and Animality: An Investigation of Absolute Freedom in Foucault’s History of Madness 59 Leonard Lawlor 4 The Order of Things: The Human Sciences are the Event of Animality 87 Saïd Chebili (Translated by Matthew Chrulew and Jefffrey Bussolini) PART 2 Power and Discipline 5 “Taming the Wild Profusion of Existing Things”? A Study of Foucault, Power, and Human/Animal Relationships 107 Clare Palmer 6 Dressage: Training the Equine Body 132 Natalie Corinne Hansen For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV vi CONTENTS 7 Foucault’s Menagerie: Cock Fighting, Bear Baiting, and the Genealogy of Human-Animal Power 161 Alex Mackintosh PART 3 Science and Biopolitics 8 The Birth of the Laboratory Animal: Biopolitics, Animal Experimentation, and Animal Wellbeing 193 Robert G. W. Kirk 9 Animals as Biopolitical Subjects 222 Matthew Chrulew 10 Biopower, Heterogeneous Biosocial Collectivities and Domestic Livestock Breeding 239 Lewis Holloway and Carol Morris PART 4 Government and Ethics 11 Apum Ordines: Of Bees and Government 263 Craig McFarlane 12 Animal Friendship as a Way of Life: Sexuality, Petting and Interspecies Companionship 286 Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel 13 Foucault and the Ethics of Eating 317 Chloë Taylor Afterword 339 Paul Patton Index 345 For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV CHAPTER 8 The Birth of the Laboratory Animal: Biopolitics, Animal Experimentation, and Animal Wellbeing Robert G. -

It's a (Two-)Culture Thing: the Laterial Shift to Liberation

Animal Issues, Vol 4, No. 1, 2000 It's a (Two-)Culture Thing: The Lateral Shift to Liberation Barry Kew rom an acute and, some will argue, a harsh, a harsh, fantastic or even tactically naive F naive perspective, this article examines examines animal liberation, vegetarianism vegetarianism and veganism in relation to a bloodless culture ideal. It suggests that the movement's repeated anomalies, denial of heritage, privileging of vegetarianism, and other concessions to bloody culture, restrict rather than liberate the full subversionary and revelatory potential of liberationist discourse, and with representation and strategy implications. ‘Only the profoundest cultural needs … initially caused adult man [sic] to continue to drink cow milk through life’.1 In The Social Construction of Nature, Klaus Eder develops a useful concept of two cultures - the bloody and the bloodless. He understands the ambivalence of modernity and the relationship to nature as resulting from the perpetuation of a precarious equilibrium between the ‘bloodless’ tradition from within Judaism and the ‘bloody’ tradition of ancient Greece. In Genesis, killing entered the world after the fall from grace and initiated a complex and hierarchically-patterned system of food taboos regulating distance between nature and culture. But, for Eder, it is in Israel that the reverse process also begins, in the taboo on killing. This ‘civilizing’ process replaces the prevalent ancient world practice of 1 Calvin. W. Schwabe, ‘Animals in the Ancient World’ in Aubrey Manning and James Serpell, (eds), Animals and Human Society: Changing Perspectives (Routledge, London, 1994), p.54. 1 Animal Issues, Vol 4, No. 1, 2000 human sacrifice by animal sacrifice, this by sacrifices of the field, and these by money paid to the sacrificial priests.2 Modern society retains only a very broken connection to the Jewish tradition of the bloodless sacrifice. -

Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(In)Ing the Other in the Digital Turn

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 8.1. | 2020 Ubiquitous Visuality Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.1957 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference Diane Leblond, “Ways of Seeing Animals”, InMedia [Online], 8.1. | 2020, Online since 15 December 2020, connection on 26 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.1957 This text was automatically generated on 26 January 2021. © InMedia Ways of Seeing Animals 1 Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Introduction. Looking at animals: when visual nature questions visual culture 1 A topos of Western philosophy indexes animals’ irreducible alienation from the human condition on their lack of speech. In ancient times, their inarticulate cries provided the necessary analogy to designate non-Greeks as other, the adjective “Barbarian” assimilating foreign languages to incomprehensible birdcalls.1 To this day, the exclusion of animals from the sphere of logos remains one of the crucial questions addressed by philosophy and linguistics.2 In the work of some contemporary critics, however, the tenets of this relation to the animal “other” seem to have undergone a change in focus. With renewed insistence that difference is inextricably bound up in a sense of proximity, such writings have described animals not simply as “other,” but as our speechless others. This approach seems to find particularly fruitful ground where theory proposes to explore ways of seeing as constitutive of the discursive structures that we inhabit. -

Critical Animal Studies: an Introduction by Dawne Mccance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto

The Goose Volume 13 | No. 1 Article 25 8-1-2014 Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Follow this and additional works at / Suivez-nous ainsi que d’autres travaux et œuvres: https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose Recommended Citation / Citation recommandée Collard, Rosemary-Claire. "Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance." The Goose, vol. 13 , no. 1 , article 25, 2014, https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose/vol13/iss1/25. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Goose by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cet article vous est accessible gratuitement et en libre accès grâce à Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Le texte a été approuvé pour faire partie intégrante de la revue The Goose par un rédacteur autorisé de Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Pour de plus amples informations, contactez [email protected]. Collard: Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Made, not born, machines this reduction is accomplished and what its implications are for animal life and Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction death. by DAWNE McCANCE After a short introduction in State U of New York P, 2013 $22.65 which McCance outlines the hierarchical Cartesian dualism (mind/body, Reviewed by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE human/animal) to which her book and COLLARD critical animal studies’ are opposed, McCance turns to what are, for CAS The field of critical animal scholars, familiar figures in a familiar studies (CAS) is thoroughly multi- place: Peter Singer and Tom Regan on disciplinary and, as Dawne McCance’s the factory farm. -

Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements

Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 5 2016 Free Tilly?: Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements Becky Boyle Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse Part of the Law Commons Publication Citation Becky Boyle, Free Tilly?: Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements, 4 Ind. J. L. & Soc. Equality 169 (2016). This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 4, Issue 2 FREE TILLY?: LEGAL PERSONHOOD FOR ANIMALS AND THE INTERSECTIONALITY OF THE CIVIL & ANIMAL RIGHTS MOVEMENTS BECKY BOYLE INTRODUCTION In February 2012, the District Court for the Southern District of California heard Tilikum v. Sea World, a landmark case for animal legal defense.1 The organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filed a suit as next friends2 of five orca whales demanding their freedom from the marine wildlife entertainment park known as SeaWorld.3 The plaintiffs—Tilikum, Katina, Corky, Kasatka, and Ulises—were wild born and captured to perform at SeaWorld’s Shamu Stadium.4 They sought declaratory and injunctive relief for being held by SeaWorld in violation of slavery and involuntary servitude provisions of the Thirteenth Amendment.5 It was the first court in U.S. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in Society, Culture and the Media

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in society, culture and the media List of readings Approved by the board of the Department of Communication and Media 2019-12-03 Introduction to the critical study of human-animal relations Adams, Carol J. (2009). Post-Meateating. In T. Tyler and M. Rossini (Eds.), Animal Encounters Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 47-72. Emel, Jody & Wolch, Jennifer (1998). Witnessing the Animal Moment. In J. Wolch & J. Emel (Eds.), Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature- Culture Borderlands. London & New York: Verso pp. 1-24 LeGuin, Ursula K. (1988). ’She Unnames them’, In Ursula K. LeGuin Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences. New York, N.Y.: New American Library. pp. 1-3 Nocella II, Anthony J., Sorenson, John, Socha, Kim & Matsuoka, Atsuko (2014). The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies: The Rise of Intersectional Animal Liberation. In A.J. Nocella II, J. Sorenson, K. Socha & A. Matsuoka (Eds.), Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation. New York: Peter Lang. pp. xix-xxxvi Salt, Henry S. (1914). Logic of the Larder. In H.S. Salt, The Humanities of Diet. Manchester: Sociey. 3 pp. Sanbonmatsu, John (2011). Introduction. In J. Sanbonmatsu (Ed.), Critical Theory and Animal Liberation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1-12 + 20-26 Stanescu, Vasile & Twine, Richard (2012). ‘Post-Animal Studies: The Future(s) of Critical Animal Studies’, Journal of Critical Animal Studies 10(2), pp. 4-19. Taylor, Sunara. (2014). ‘Animal Crips’, Journal for Critical Animal Studies. 12(2), pp. 95-117. /127 pages Social constructions, positions, and representations of animals Arluke, Arnold & Sanders, Clinton R. -

Centre for the Study of Social and Political

CENTRE FOR THE STUDY ABOUT OF SOCIAL AND The Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements was established in 1992, and since then has helped the University of Kent gain wider POLITICAL recognition as a leading institution in the study of social and political movements in the UK. The Centre has attracted research council, European Union, and charitable foundation funding, and MOVEMENTS collaborated with international partners on major funding projects. Former staff members and external associates include Professors Mario Diani, Frank Furedi, Dieter Rucht, and Clare Saunders. Spri ng 202 1 Today, the Centre continues to attract graduate students and international visitors, and facilitate the development of collaborative research. Dear colleagues, Recent and ongoing research undertaken by members includes studies of Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, veganism and animal rights. Things have been a bit quiet in the center this year as we’ve been teaching online and unable to meet in person. That said, social The Centre takes a methodologically pluralistic movements have not been phased by the pandemic. In the US, Black and interdisciplinary approach, embracing any Lives Matter protests trudge on, fueled by the recent conviction of topic relevant to the study of social and political th movements. If you have any inquiries about George Floyd’s murder on April 20 and the police killing of 16 year old Centre events or activities, or are interested in Ma'Khia Bryant in Ohio that same day. Meanwhile, the killing of Kent applying for our PhD programme, please contact resident Sarah Everard (also by a police officer) spurred considerable Dr Alexander Hensby or Dr Corey Wrenn. -

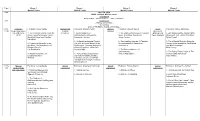

2010 Schedule Chart (8 1/2 X 14 In

Time Room 1. Room 2. Room 3. Room 4. Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center 9:00 April 10, 2010 SUNY Cortland, Moffett Center Registration Sarat Colling - Elizabeth Green – Ashley Mosgrove 9:30 Introduction Anthony J. Nocella, II Welcoming Andrew Fitz-Gibbon and Mechthild Nagel 10:00 – Academic Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animals and Facilitator: Ronald Pleban Species Facilitator: Doreen Nieves Social Facilitator: Ashley Mosgrove 11:20 Repression Book Cultural Inclusion Movement Talk (AK Press, 1. The Carceral Society: From the Practices 1 Animal Subjects in 1. The Politics of Inclusion: A Feminist Strategy and 1. DIY Media and the Animal Rights 2010) Prison Tower to the Ivory Tower Anthropological Perspective Space to Critique Speciesism Tactic Analysis Movement: Talk - Action = Nothing Mechthild Nagel and Caroline Alessandro Arrigoni Jenny Grubbs Dylan Powell Kaltefleiter 2. An American Imperial Project: 2. Transcending Species: A Feminist 2. The Influential Activist: Using the 2. Regimes of Normalcy in the The Role of Animal Bodies in the Re-examination of Oppression Science of Persuasion to Open Minds Academy: The Experiences of Smithsonian-Theodore Roosevelt Jeni Haines and Win Campaigns Disabled Faculty African Expedition, 1909-1910. Nick Cooney Liat Ben-Moshe Laura Shields 3. The Reasonableness of Sentimentality 3. The Role of Direct Action in The 3. Adelphi Recovers „The 3. Conservation perspectives: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon Animal Rights Movement Lengthening View International wildlife priorities, Carol Glasser Ali Zaidi individual animals, and wildlife management strategies in Kenya Stella Capoccia 11:30- Species Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animal Facilitator: Anastasia Yarbrough Animal Facilitator: Brittani Mannix Animal Facilitator: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon 1:00 Relationships Exploitation Exploitation Exploitation and Domination 1. -

Death-Free Dairy? the Ethics of Clean Milk

J Agric Environ Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9723-x ARTICLES Death-Free Dairy? The Ethics of Clean Milk Josh Milburn1 Accepted: 10 January 2018 Ó The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract The possibility of ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy produced without the need for cows—has been championed by several charities, companies, and individuals. One can ask how those critical of the contemporary dairy industry, including especially vegans and others sympathetic to animal rights, should respond to this prospect. In this paper, I explore three kinds of challenges that such people may have to clean milk: first, that producing clean milk fails to respect animals; second, that humans should not consume dairy products; and third, that the creation of clean milk would affirm human superiority over cows. None of these challenges, I argue, gives us reason to reject clean milk. I thus conclude that the prospect is one that animal activists should both welcome and embrace. Keywords Milk Á Food technology Á Biotechnology Á Animal rights Á Animal ethics Á Veganism Introduction A number of businesses, charities, and individuals are working to develop ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy products created by biotechnological means, without the need for cows. In this paper, I complement scientific work on this possibility by offering the first normative examination of clean dairy. After explaining why this question warrants consideration, I consider three kinds of objections that vegans and animal activists may have to clean milk. First, I explore questions about the use of animals in the production of clean milk, arguing that its production does not involve the violation of & Josh Milburn [email protected] http://josh-milburn.com 1 Department of Politics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK 123 J. -

Animal Ethics and the Political

This is a repository copy of Animal Ethics and the Political. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/103896/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Cochrane, A. orcid.org/0000-0002-3112-7210, Garner, R. and O'Sullivan, S. (2016) Animal Ethics and the Political. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy. ISSN 1369-8230 https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2016.1194583 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy on 09/06/2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/13698230.2016.1194583. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Alasdair Cochrane, Robert Garner and Siobhan O’Sullivan Animal Ethics and the Political (forthcoming in Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy) Some of the most important recent contributions to normative debates concerning our obligations to nonhuman animals appear to be somehow ‘political’.i Certainly, many of those contributions have come from those working in the field of political, rather than moral, philosophy. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations.