12 Ict Policy Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efstathiou N.Pdf (1.773Mb)

Assessing the influence of radio advertising on consumer purchasing decisions ND Efstathiou orcid.org 0000-0002-1752-3807 Mini-dissertation accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Business Administration at the North-West University Supervisor: Prof CA Bisschoff Graduation: May 2019 Student number: 29788285 ABSTRACT Radio advertising is an advertising platform that has been used by brands, products and services since 1922. The influence of radio advertising on a consumer’s purchase decision is tough to determine, the research that is available on radio advertising, in general, is far less in comparison to other advertising research studies in the marketing of brands, products and services. This study aims to determine the impact of radio advertising on a consumer purchase decision. The majority of research studies rely on the effect of television and print advertising, and recently internet advertising has shown a higher engagement level for consumers to influence purchase decisions. The disruptive nature of internet advertising has had an influence on the revenue generation for traditional platforms such as radio, print and television. Radio advertising is a platform used mostly by local businesses on a local radio station in the business’s vicinity. Research in the marketing of brands, products and services have included radio advertising, including the singularity of a message of a radio advertisement message recall-analysis. Traditional media are used for branding, and to action a sales promotion to drive revenue generation and profitability. Advertising does have a material influence on consumers’ purchase decisions. The question in this study determines the influence radio would have on that decision. -

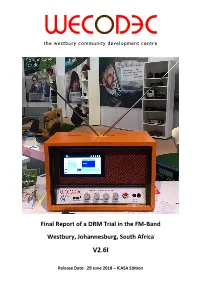

Final Report of a DRM Trial in the FM-Band

WWEECCOD ∃C the westbury community development centre Final Report of a DRM Trial in the FM‐Band Westbury, Johannnesburg, South Africa V2.6I Release Date: 29 June 2018 – ICASA Edition Document History Version Date Item changed/added 0.1 05 June 2017 Template prepared from license application, research, strategy and regulatory documentation 0.2 09 June 2017 Changed/added: Structure, objectives, timelines, systems, methodology 0.3 12 June 2017 Changed: Structure; Added: Results 0.4 13 June 2017 Added: Contributors, Copyright 0.5 22 June 2017 Added: Drive-by measurements, propagation Maps, and explanations 1.0 30 June 2017 Touch-ups 1.4 07 July 2017 About WECODEC and Project Partners, final touch-ups and release 2.0 15 April 2018 Added measurements in North Johannesburg/Gauteng 2.1 22 April 2018 Added Title Picture, added content, touch-ups 2.4 23 April 2018 Added Content in chapters Objectives, Reasons, Benefits, final touch-ups 2.5 15 May 2018 Touch-ups after review with project partners 2.6 29 June 2018 Foreword from the Chairperson/Changed Title Picture By Johannes von Weyssenhoff Project Partners: The Westbury Community The Westbury Youth The WECODEC Board Thembeka & Associates BluLemon, Edenvale, South Africa BBC World Service, London, UK Fraunhofer IIS, Erlangen, Germany STARWAVES, Switzerland The DRM Consortium Copyright All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and may be proprietary in nature. Please obtain written permission from the Technology and Knowledge Base Department of The Westbury Community Development Centre (WECODEC) via email: [email protected] prior to reproducing any part of this document, in whole or in part. -

BC-DX 280 31 Dec 1996 ANGUILLA New 6090 Khz Carib

BC-DX 280 31 Dec 1996 ________________________________________________________________________ ANGUILLA New 6090 kHz Caribbean Beacon 0610 //5935 (non Aguilla, via WWCR) Cr. Gene Scott talking about first night. Broadcasting only at nights with 80 kW while testing tx. They will announce day freq on Sun, Dec 29. Asking for reception reports. Recheck 0735 UTC and they were gone. (Hans Johnson-USA, Dec 28) Thanks to a tip from Hans Johnson and Cumbre DX, 6090 kHz Caribbean Beacon noted with an open carrier at 0340 UTC, audio started 0400 UTC sharp //WWCR-5035, and the first 10 minutes Scott was asking for telephone reports on the signal. Here on the NRD-535D, on the high 300-ft inverted-L it is +50dB/s9, the low 50-ft doublet (with the high skywave angle) it is +60dB/s9. Telephone reports started up coast to coast by 0413 UTC. Hardly difficult. (Tom Sundstrom-NJ, 29 Dec) 6090 kHz - 0410 UTC, rock mx, Dr. Scott talking about the new txer, saying at one point it was "just shy of" 75 kw, at another 80 kw, "100% modulation." Invited calls to their usual phone numbers, and ran down the calls they had been getting from listeners, mostly west coasters, TX, KS, etc, all of whom seemed to be having better reception than I was. Good strength, though I would have expected better; a hum on the signal; and a bad fqy in my area, with splatter in both directions from DW powerhouses on 6085 and 6100 until DW closes at 0600. Better, and dominant, thereafter, but nowhere near as good as the //WWCR-5935 signal. -

African Studies Abstracts Online: Number 25, 2009 Boin, M.; Polman, K.; Sommeling, C.M.; Doorn, M.C.A

African Studies Abstracts Online: number 25, 2009 Boin, M.; Polman, K.; Sommeling, C.M.; Doorn, M.C.A. van Citation Boin, M., Polman, K., Sommeling, C. M., & Doorn, M. C. A. van. (2009). African Studies Abstracts Online: number 25, 2009. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13427 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13427 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Number 25, 2009 AFRICAN STUDIES ABSTRACTS ONLINE Number 25, 2009 Contents Editorial policy............................................................................................................... iii Geographical index ....................................................................................................... 1 Subject index................................................................................................................. 3 Author index.................................................................................................................. 7 Periodicals abstracted in this issue............................................................................... 14 Abstracts ....................................................................................................................... 18 Abstracts produced by Michèle Boin, Katrien Polman, Tineke Sommeling, Marlene C.A. Van Doorn ii EDITORIAL POLICY African Studies Abstracts Online provides an overview of articles -

Interim Report of a DRM Mode E Trial in South Africa

WECOD ∃C the westbury community development centre IT 4455/00 Interim Report of a DRM Mode E Trial in South Africa V1.4 Release Date: 08 July 2017 Project Partners: Kofifi Media Group, Roodepoort, South Africa BluLemon, Edenvale, South Africa CR Electronics, Springs, South Africa Genssoft Technologies, Midrand, South Africa BBC World Service, London, UK Fraunhofer IIS, Erlangen, Germany WECODEC DRM Trial · Interim Report July 2017 Page 1 Document History Version Number Date Item changed/added 0.1 05 June 2017 Template prepared from license application, research, strategy and regulatory documentation 0.2 09 June 2017 Changed/added: Structure, objectives, timelines, systems, methodology 0.3 12 June 2017 Changed: Structure; Added: Results 0.4 13 June 2017 Added: Contributors, Copyright 0.5 22 June 2017 Added: Drive-by measurements, propagation Maps, and explanations 1.0 30 June 2017 Touch-ups 1.4 07 July 2017 About WECODEC and Project Partners, final touch-ups and release Copyright All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and may be proprietary in nature. Please obtain written permission from the Westbury Community Development Centre (WECODEC) via email: [email protected] prior to reproducing any part of this document, in whole or in part. WECODEC DRM Trial · Interim Report July 2017 Page 2 Contents 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 3: the Current State of the South African Communications Sector

Chapter 3: The Current State of the South African Communications Sector 3.1 Electronic Communications Sector 3.1.1 Legislative and policy environment The 1996 White Paper on Telecommunications envisioned a policy environment in which the telecommunications sector balances the provision of basic universal service to disadvantaged rural and urban communities with the delivery of high-level services capable of meeting the needs of a growing South African economy. The White Paper sought to, amongst other things, provide for a new market structure that orientates the sector towards accelerated development and universal service, as well as take into account technological and international trends. The market structure entailed a period of exclusivity for Telkom. After this exclusivity period, the White Paper envisaged an environment whereby various telecommunications market segments would be liberalised in a phased process, put into motion and overseen by the Regulator. This policy provision enabled the licensing of the Second National Operator in the fixed-line market, and three mobile operators. In terms of the ownership, investment and financing, the state retained a majority shareholding in Telkom and shareholding in Vodacom. The Altech Judgement in 2008 cleared the way for Value Added Network Service (VANS) licencees to self-provide their own telecommunications network, facilities and services. A Telecommunications Regulator called the South African Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (SATRA) and the Universal Service and Access Agency of South Africa (USAASA) were set up. SATRA was established to regulate telecommunications in the public interest and also manage the radio frequency spectrum with the exception of the broadcasting services frequency bands which were then administered by the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA). -

BC-DX 401 06 Jan 1999 AFGHANISTAN 7079V, Voice Of

BC-DX 401 06 Jan 1999 ________________________________________________________________________ AFGHANISTAN 7079v, Voice of Shariah, Kabul, 1300-1715 Jan 2, mostly relig progr in the month of fasting, currently hrd in Pa/Da with good quality sigs. Maybe the old tx given a clean up in the New Year. Ar at 1645 and En 1700. (Sarath Weerakoon-CLN 4S5SL UADX, via NU, Jan 2) ALGERIA 1550 National Radio of SADR, nx in Ar, many mentions of Sahara, Dec 1, 2220. (Sheigra Dxpedition to north west Sutherland, with Dave Kenny, Graham Powell, Tony Rodgers, in BDXC-UK, Communication, Jan) AUSTRALIA Latest sked from Radio Australia: 0000-0100 En 9660 12080 15240 17715 17750 17795 21740 0000-0100 Vn 15415 0100-0200 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 17715 17750 17795 21740 0100-0700 Grandstand* 9660 12080 15240 17715 17750 Sat 0200-0300 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17715 17750 21725 0200-0700 Grandstand* 9660 12080 15240 17715 17750 Sun 0300-0400 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17750 21725 0400-0500 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17715 17750 21725 0500-0600 En 9660 12080 15240 15510 17715 21725 0500-0600 Khmer 15415 17750 0600-0800 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17715 17750 21725 0800-0900 En 5995 9580 9710 12080 15415 15510 17750 21725 0900-1100 En 6080 9580 11880 17750 0900-1200 Tok Pisin 5995 6020 9710 12080 1100-1200 En 6080 9580 1100-1230 Ch 9500 11880 1200-1400 En 5995 6020 6080 9580 1230-1330 Vn 9500 11880 1330-1430 Vn 9500 11660 1400-1430 En 5995 9580 1430-1700 En 5995 9500 9580 11660 1700-1800 En 5995 9500 9580 11880 1800-2000 En 6080 7240 9500 9580 9660 11880 2000-2100 En 9500 9580 9660 11880 12080 2000-2100 Tok Pisin 6080 7240 Su-Th 2100-2130 En 7240 9500 9660 11880 12080 17715 21740 2130-0000 BI 11695 15415 2130-2200 En 7240 9660 11880 12080 17715 21740 2200-2300 Ch 15240 2200-2300 En 17715 17795 21740 2300-0000 En 9660 12080 17715 17795 21740 2300-0000 Khmer 15240 *Grandstand is a weekend sports progr. -

Appendix 08. Technology

APPENDIX EIGHT Understanding Technologies and Education Clusters Chapter three of this report focuses on understanding educational technologies and their educational applications. This could not have been possible, without establishing a clear understanding of the technologies themselves. In this appendix we briefly describe a range of technologies of relevance to this study: • terrestrial radio and television; • satellite bandwidth; • telecommunications; and • computer technologies. We then focus on education cluster environments specifically, describing each element of the cluster and its associated costs. Finally we consider the technology infrastructure in key educational networks - schools, Multi-purpose Community Centres and Libraries. This appendix has been used as source information to inform the technology options and to generate the costing models used. TERRESTRIAL BROADCASTING Terrestrial, as opposed to satellite broadcasting is a ground-based transmission network operation for radio and television. Analogue signals are transmitted from a central transmission station to a local transmitter, which then sends the signal to the receiving equipment, which can either be a radio or television. Each broadcaster has its own in-house transmitter, whose main func tion is to amplify the studio signal in order to make it accessible for broadcasting. This does not necessarily guarantee that the transmitted signal will reach every user, because terrestrial signal operates like a torch beam. If there is an obstacle betw een the beam and the object of focus (depending on the size and density of that obstacle), less light or no light at all will go through. Geographical features like hills and mountains are the most prevalent and obvious obstacles for the transmission of terrestrial broadcasting. -

Government Gazette

Government Gazette REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Vol. 447 Pretoria 30 September 2002 No. 23873 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-123-22 Prevention is the cure STAATSKOERANT, 30 SEPTEMBER 2002 No. 23873 3 GENERALNOTICE NOTICE 1825 OF 2002 INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITYOF SOUTH AFRICA (ICASA) e/ NOTICE OF PUBLICATION OF THE DISCUSSION PAPER ON THE REVIEW OF OWNERSHIP AND CONTROLOF BROADCASTING SERVICES AND EXISTING COMMERCIALSOUND BROADCASTING LICENCES The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa ("the Authority") hereby, in accordance with section28 of the Independent BroadcastingAuthority Act, as amended, 1993, publishes its Discussion Paper onthe Review of Ownership and Controlof Broadcasting Services and Existing Commercial Sound Broadcasting Licences Interested parties are invited to: (a) obtain from the Authority or from the Authority's website (m.icasa.orq.za) a copy of the Discussion Paper, and (b) submit written representations by post, or fax, or e-mail or delivered by hand to: Policy Research Development Department Independent Communications Authority of South Africa 164 Katherine Street, Pinmill Farm, Block D Sandton OR Private BagX1 0002 Sandton 21 46 OR Fax: (01 1) 448 241 4 or e-mail address: [email protected] [email protected]. Any interested person or organisation who submits written representations should indicate whether they require an opportunityto make oral presentation atthe hearings. The closing datefor the receipt of representations 06is DecemberOctober 2002, at 16h30. 27 September 2002 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Final Project Report English Pdf 65.44 KB

CEPF FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT I. BASIC DATA Organization Legal Name: University of Stellenbosch Project Title (as stated in the grant agreement): Karoo Veld: Ecology & Management Implementation Partners for this Project: Project Dates (as stated in the grant agreement): January 1, 2004 – July 31, 2006 Date of Report (month/year): October 2006 II. OPENING REMARKS Provide any opening remarks that may assist in the review of this report. SKEP, though the CEPF, made it possible to publish the book, “Karoo Veld: Ecology and Management” in English and in Afrikaans and at an affordable price to the custodians of the Karoo. An earlier, shorter, English language publication – written by Sue Milton and Richard Dean and published by the Agricultural Research Council – appeared in 1996, with the aim of placing the understanding of Karoo veld ecology and management, which had been gained from research and interactions with farmers, into a form that would be accessible and useful to them. This book was rapidly sold out. Ten years later it became clear that a new version was needed, and that it should be published in the two primary languages of the Karoo – English and Afrikaans. Collaboration began between Sue Milton, Richard Dean, Karen Esler and a range of other Karoo experts who willingly gave their time to contribute sections to the book. The project took about two years from start to finish, but in reality it reflects a culmination of at least a century of observation over 60 cumulative years of life and research in the Karoo for Esler, Milton & Dean. III. ACHIEVEMENT OF PROJECT PURPOSE Project Purpose: To ensure that Karoo stakeholders (including Commercial farmers; New farmers with greatest potential negative or positive effect; Game farmers; Researchers; Conservation managers; Extension officers) understand, use and stimulate replication of appropriate management techniques that are described in the book for habitats, vegetation, soils and animals of the semi-arid Karoo. -

The Whiteness of South African English Radio Drama

THE WHITENESS OF SOUTH AFRICAN ENGLISH RADIO DRAMA: A POSTCOLONIAL STUDY OF THE RISE, DECLINE AND DEMISE OF A DRAMATIC SUB-GENRE by MARGARET ELAINE LOGAN submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject THEORY OF LITERATURE at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF MARISA KEURIS NOVEMBER 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express her appreciation to the following for their contribution to the formulation, execution and presentation of this study: Prof. Marisa Keuris, Head of the Department of Afrikaans and Theory of Literature, UNISA, Pretoria, for her encouragement, guidance and support. Her interest in radio drama, expressed at an early stage in my studies at UNISA, has been a source of inspiration for me: Retha Roux of the SABC Sound Archives, Johannesburg, for the provision of invaluable information, and her unfailingly prompt response to my many queries: Former radio drama practitioners, friends and former colleagues, who completed my questionnaires or gave interviews, most notably Nigel Vermaas, Jack Mullen and Bev Peirce, whose valuable insights, opinions and recollections form such an important contribution to this work: Old Time Radio experts and archivists Frans Erasmus and Kevan Mardon, for their readiness to share their expertise, including recordings and magazine articles: Claire Welch, Technical Support Executive of the South African Advertising Foundation, for her helpful assistance, and the provision of radio audience statistics: My husband and children for their patience and encouragement. ii ABSTRACT An exposition of South African English radio drama tracing the historical, cultural and political issues which led to the demise of the art form in 1999, and its resurrection at ICASA’s insistence in 2006. -

THESIS J Praeg

The political promise of choreography in performance and/as research: First Physical Theatre Company’s manifesto and repertory, 1993-2015 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for PhD degree Rhodes University Juanita Praeg 682F2501 PhD (Full Thesis) Drama Department Supervisor: Professor Gary Gordon (Rhodes University) [email protected] [email protected] Co-Supervisor: Professor Ketu Katrak (University of California, Irvine) khkatrak@uci .edu Date of final submission: December 2019 ABSTRACT This study redefines the political in dance by drawing on the scholarly concept of the “choreopolitical” (André Lepecki) and extending it into analysing related concepts such as the “postdramatic” (Hans-Thies Lehmann), performance and/as research, among others from Performance Studies scholarship as well as from First Physical Theatre Company’s pioneering legacy of production, pedagogy and research in making Phyical Theatre performance. Following from the notion that performance is both a site and a method of study/knowing, the research invites a rethinking of the relationship between art (performance), epistemology and the political, in the sense that performance becomes a way, not of simply re-presenting the political but, as its own way of knowing, actively questioning the very categories on which the political is premised. The argument for Physical Theatre as having nascent potential to invoke what I call “the power of the small” is analysed as a choreopolitical method and community of practice that has a generative capacity to produce the “intimate revolts” (Julia Kristeva) or body of questions that can perform the imaginative curiosities/forms required to create provocative, subversive, ethical, reflexive and charged performance.