Unified Transport Authorities and Centralised Ticketing Systems Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Report 03/2014 February 2014 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Contents Summary 5 Introduction 6 Preface 6 Key definitions 6 The incident 7 Summary of the incident 7 Context 7 Events preceding the incident 9 Events following the incident 11 Consequences of the incident 11 The investigation 12 Sources of evidence 12 Key facts and analysis -

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Oyster Conditions of Use on National Rail Services

Conditions of Use on National Rail services 1 October 2015 until further notice 1. Introduction 1.1. These conditions of use (“Conditions of Use”) set out your rights and obligations when using an Oyster card to travel on National Rail services. They apply in addition to the conditions set out in the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, which you can view and download from the National Rail website nationalrail.co.uk/nrcoc. Where these Conditions of Use differ from the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, these Conditions of Use take precedence when you are using your Oyster card. 1.2 When travelling on National Rail services, you will also have to comply with the Railway Byelaws. You can a get free copy of these at most staffed National Rail stations, or download a copy from the Department for Transport website dft.gov.uk. 1.3 All Train Companies operating services into the London Fare Zones Area accept valid Travelcards issued on Oyster cards, except Heathrow Express and Southeastern High Speed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International. In addition, the following Train Companies accept pay as you go on Oyster cards for travel on their services within the London National Rail Pay As You Go Area. Abellio Greater Anglia Limited (trading as Greater Anglia) The Chiltern Railway Company Limited (trading as Chiltern Railways) First Greater Western Limited (trading as Great Western Railway) (including Heathrow Connect services between London Paddington and Hayes & Harlington) GoVia Thameslink Railway Limited (trading as Great Northern, as Southern and as Thameslink) London & Birmingham Railway Limited (trading as London Midland) London & South Eastern Railway Company (trading as Southeastern) (Special fares apply on Southeaster highspeed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International). -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

TTF Smartcard Ticketing on Public Transport 2010

Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) Position Paper Smartcard ticketing on public transport July 2010 Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) is a national, Member‐funded CEO forum, advocating the public policy interests of the 200 most prestigious corporations and institutions in the Australian tourism, transport, aviation & investment sectors. CONTENTS OVERVIEW 2 SMARTCARD TECHNOLOGY 3 ADVANTAGES OF SMARTCARD TICKETING 3 CHALLENGES FOR IMPLEMENTATION 6 SMARTCARD TICKETING IN AUSTRALIA 8 SMARTCARD TICKETING INTERNATIONALLY 10 INNOVATION IN SMARTCARD TECHNOLOGY 12 LOOKING AHEAD 14 CONCLUDING REMARKS 14 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: CAROLINE WILKIE NATIONAL MANAGER, AVIATION & TRANSPORT TOURISM & TRANSPORT FORUM (TTF) P | 02 9240 2000 E | [email protected] www.ttf.org.au In short: 1. Smartcard ticketing provides convenience for commuters and efficiency gains for transport service providers. 2. Smartcard systems have been introduced in Australian cities with varying degrees of success. 3. International experience suggests that successful implementation may take many years, and difficulties are commonplace. 4. Overall, the benefits of smartcard ticketing overwhelmingly outweigh the costs and challenges that may arise in implementation. Overview Smartcard technology is being implemented around the world as a substitute for cash transactions in various capacities. When applied to public transport fare collection, smartcards eliminate the need for commuters to queue for tickets and reduce the burden on transport providers to process fare transactions. In recent years, benefits such as decreased travel times and general convenience to commuters have driven a shift towards smartcard ticketing systems on public transport systems in Australia and around the world. As well as providing more efficient transport services to commuters, smartcard ticketing systems enable service providers and transit authorities to collect comprehensive data on the travel behaviour of commuters. -

Making Rail Accessible: Helping Older and Disabled Customers

TfL Rail Making rail accessible: Helping older and disabled customers May 2016 MAYOR OF LONDON Contents Our commitment to you page 3 Commitments page 5 Assistance for passengers page 6 Alternative accessible transport page 9 Passenger information page 10 Fares and tickets page 12 At the station page 16 On the train page 17 Making connections page 19 Accessible onward transport page 20 Disruption to facilities and services page 21 Contact us page 23 Station accessibility information page 24 Contact information back page 2 Our commitment to you TfL Rail is managed by Transport for London (TfL) and operated by MTR Crossrail. We operate rail services between Liverpool Street and Shenfield. At TfL Rail, we are committed to providing you with a safe, reliable and friendly service. We want to make sure that you can use our services safely and in comfort. 3 Our commitment to you (continued) We recognise that our passengers may have different requirements when they travel with us and we are committed to making your journey as easy as possible. This applies not only to wheelchair users, but also: • Passengers with visual or auditory impairment or learning disabilities • Passengers whose mobility is impaired through arthritis or other temporary or long term conditions • Older people • Passengers accompanying disabled children in pushchairs • Disabled passengers requiring assistance with luggage We welcome your feedback on the service we provide and any suggestions you may have for improvements. Our contact details are shown on the back page of this -

Innovation. Technology. Performance. for the URBAN RAIL COMMUNITY

Smart cities Tram-trains Ticketing Power Traction CBTC Train control Technology Mobility Telecommunications Innovation Innovation. Driverless Infrastructure Passenger Information Asset management FOR THE URBAN RAIL COMMUNITY Technology. Performance. www.terrapinn.com/railliveamericas Organized by Our Story Hall of Fame Revamped for the new year, RAIL Live! Americas 2019 is moving to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor as we build on the success of World MetroRail Congress Americas 2018, which continued our strong tradition of bringing together top leaders from the Americas’ most influential and innovative transit agencies. Andy Byford Jim Kenney 2018 leaders included Kevin Desmond, CEO of TransLink, Edward Reiskin, President Mayor Director of Transportation for the SFMTA, Jim Kenney, Mayor, City of Philadelphia New York City Transit City of Philadelphia Tom Gerend, Executive Director of KC Streetcar, Robert Puentes, President & CEO of the Eno Center for Transportation, Martin Buck, International Lead for Crossrail in London, and Lorenzo Aguilar Camelo, the General Director of Metrorrey in Monterrey, Mexico. KEY INDUSTRY DISCUSSIONS FOR 2019 WILL BE DIVIDED INTO FOUR Jascha Franklin-Hodge Bill Zebrowski Chief Information Officer BRAND NEW TRACKS: Chief Information Officer Department of Innovation & SEPTA • The Future of Mobility: Discussions around Mobility as a Service, Fare Collection, Technology, City of Boston Intermodality, Ridership, Passenger Information Systems, and First and Last Mile transport. • New Project Development: Examining Funding and Financing, Public-Private Partnerships, Procurement, Designing and Building New Metros, Light Rails, Commuter, and High-Speed Rail Lines. Meera Joshi Adam Giambrone NYC Taxi and Limousine Director, Brooklyn-Queens • Train Control: Covering ATC, CBTC, PTC, as well as the Full Spectrum of Commission Connector [Streetcars and LRT] Modernizing Signaling and Train Control Systems to Increase Safety and Capacity. -

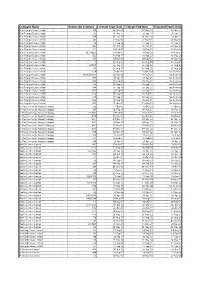

Operators Route Contracts

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

Report of the Delegation of the Panel on Transport on Its Duty Visit To

LC Paper No. CB(4)823/14-15 The Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region ___________________________________________ Delegation of the Panel on Transport Report on the duty visit to Singapore to study its experience in development and provision of public transport facilities and traffic control measures 23 to 26 September 2014 ___________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of the report 1 1.2 Background of the visit 1 1.3 Objectives of the visit 2 1.4 Membership of the delegation 3 1.5 Visit programme 3 2 Overview of the transport strategy in Singapore 2.1 Overview 4 2.2 Building up a quality public transport system 5 2.3 Maximizing road network efficiency capacity 6 2.4 Establishing a bike-friendly city 7 2.5 Enhancing accessibility to public transport 7 3 Visits and exchanges 3.1 Meeting with the Minister for Transport 8 3.2 Meeting with the representatives of the Land Transport 14 Authority 3.3 Meeting with the Chairman and Deputy Chairman of 23 the Government Parliamentary Committee for Transport 3.4 Meeting with the representatives of the SBS Transit and 29 visit to the North East Line's Operations Control Centre and the Sengkang Integrated Transport Hub 3.5 Meeting with the Director of the Hong Kong Economic 39 and Trade Office in Singapore 3.6 Visit to the Marina Bay Cruise Centre Singapore and its 43 connecting transport facilities 3.7 Visit to cycling facilities near Pasir Ris Town 47 4 Observations and conclusions 4.1 Observations 51 4.2 Conclusions 55 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 56 Acronyms and Abbreviations 57 Appendices I Visit programme 58 II List of the organizations and persons met by the delegation 59 References 61 CHAPTER 1 — INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of the report 1.1.1 A delegation of the Panel on Transport ("the Panel") of the Legislative Council visited Singapore from 23 to 26 September 2014 to study the country's experience in development and provision of public transport facilities and traffic control measures. -

Centro De Investigaciones Socioeconómicas

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE COAHUILA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIOECONÓMICAS TESIS TESIS 2020 EDUARDO GAMALIEL GARCÍA TERÁN “Convergencia en el largo plazo en el transporte público urbano de pasajeros” 1 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE COAHUILA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIOECONÓMICAS MAESTRIA EN ECONOMÍA REGIONAL MAESTRÍA EN ECONOMÍA REGIONAL TESIS “Convergencia en el largo plazo en el transporte público urbano de pasajeros” que se presenta como requisito parcial para obtener el grado de Maestro en Economía Regional EDUARDO GAMALIEL GARCÍA TERÁN Comité Evaluador: Director: Dr. Ignacio Cruz Rodríguez Codirectora: Dra. Miriam Valdés Ibarra Lectora: Dra. Alba Verónica Méndez Delgado Lector: Dr. David Casto Lugo Saltillo, Coahuila Junio de 2020 2 INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................... 5 CAPÍTULO 1. Elementos del transporte. ............................................................... 11 1.1 Movilidad ...................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Decisiones de modalidad del usuario ........................................................... 16 1.3 Función de Producción ................................................................................ 19 1.4 Competencia y cambio modal ...................................................................... 21 CAPÍTULO 2 Clasificación y operación del Transporte público ............................. 25 2.1 Clasificación del transporte: Público vs privado. ......................................... -

Rapport Financier Sncf Mobilités

31 DÉCEMBRE 2015 RAPPORT FINANCIER SNCF MOBILITÉS SNCF.COM RUBRIQUAGE O1 — RAPPORT D’ACTIVITÉ PAGE 04 O2 — COMPTES CONSOLIDÉS ANNUELS PAGE 26 O3 — RAPPORT SUR LE GOUVERNEMENT D’ENTREPRISE ET LE CONTRÔLE INTERNE DU GROUPE SNCF MOBILITÉS PAGE 111 02 — RAPPORT FINANCIER SNCF MOBILITÉS 2015 RUBRIQUAGE ATTESTATION DES RESPONSABLES DU RAPPORT FINANCIER LA PLAINE SAINT-DENIS, LE 12 FÉVRIER 2015 Nous attestons, à notre connaissance, que les comptes consolidés annuels sont établis conformément aux normes comptables applicables et donnent une image fidèle du patrimoine, de la situation financière et du résultat de la société et de l’ensemble des entreprises comprises dans la consolidation, et que le rapport d’activité annuel ci-joint présente un tableau fidèle de l’évolution des affaires, des résultats et de la situation financière de la société et de l’ensemble des entreprises comprises dans la consolidation ainsi qu’une description des principaux risques et incertitudes auxquels elles sont confrontées. GUILLAUME PEPY MATHIAS EMMERICH LE PRÉSIDENT LE DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DÉLÉGUÉ PERFORMANCE RAPPORT FINANCIER SNCF MOBILITÉS 2015— 03 RUBRIQUAGE O1 — RAPPORT ANNUEL D’AC TI VITÉ Normes IFRS. En millions d’euros 04 — RAPPORT FINANCIER SNCF MOBILITÉS 2015 RUBRIQUAGE LE GROUPE SNCF MOBILITÉS RÉSULTATS ET SITUATION GOUVERNEMENT EN 2015 06 FINANCIÈRE DU GROUPE 09 D’ENTREPRISE 25 1. Événements majeurs de l’exercice 06 4. Commentaire général 11. Le Conseil d’administration 25 2. Chiffres clés 08 sur les résultats du groupe 09 12. L’équipe dirigeante 25 3. Événements postérieurs 5. Activités et résultats des secteurs 12 à la clôture 08 6. Investissements nets et endettement net 18 7. -

Metrobus of 9 De Julio Avenue, PMI Argentina

PM World Journal Project Management Update from Argentina Vol.VI, Issue VI – June 2017 Cecilia Boggi www.pmworldjournal.net Regional Report Project Management update from Argentina By Cecilia Boggi, PMP International Correspondent Buenos Aires, Argentina A successful Argentine Project in public transportation has recently received an international award. It’s the Project of the "Metrobus of 9 de Julio Avenue" in the city of Buenos Aires, which was chosen as the "Greatest Achievement of World Transportation" by the International Transport Forum, as it constitutes "a good example of an effective framework of cooperation between diverse actors" of the sector. The International Transport Forum is an intergovernmental organization integrated with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which carries out its activities autonomously and the Argentine project was chosen from 57 projects from China, Germany, France, United Kingdom, India, Japan, Spain, Switzerland, United States, Korea, Canada, Mexico, Russia, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Denmark and Finland, among others. The Metrobus is a transportation system that combines traditional and articulated buses with exclusive lanes that reduce travel times and improves environmental quality. In the city of Buenos Aires, the first Metrobus was inaugurated in 2011 on Juan B. Justo Avenue, between Liniers and Palermo districts, and in 2013 the same system was implemented on 9 de Julio Avenue. When this project began, it generated many controversies because its construction modified the view of the mythical 9 de Julio Avenue, the widest in the world according to the “Porteños”- inhabitants of the city of Buenos Aires-, in the middle of which is the Obelisco, the largest emblem of the city of Buenos Aires.