Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct-82.Pdf

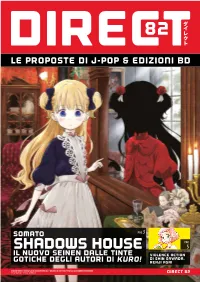

82 LE PROPOSTE DI J-POP & EDIZIONI BD SOMATO PAG 3 PAG SHADOWS HOUSE 5 il nuovo seinen dalle tinte violence action di Shin Sawada, gotiche degli autori di Kuro! Renji Asai SHADOW HOUSE © 2018 by Somato 2018/SHUEISHA Inc. | VIOLENCE ACTION ©2017 Renji ASAI, Shin SAWADA/SHOGAKUKAN. COPIA GRATUITA - VIETATA LA VENDITA DIRECT 82 DAISY JEALOUSY© 2020 Ogeretsu Tanaka/Libre Inc. 82 CHECKLIST! SPOTLIGHT ON DIRECT è una pubblicazione di Edizioni BD S.r.l. Viale Coni Zugna, 7 - 20144 - Milano tel +39 02 84800751 - fax +39 02 89545727 www.edizionibd.it www.j-pop.it Coordinamento Georgia Cocchi Pontalti Art Director Giovanni Marinovich Hanno collaborato Davide Bertaina, Jacopo Costa TITOLO ISBN PREZZO DATA DI USCITA Buranelli, Giorgio Cantù, Ilenia Cerillo, Francesco INDICATIVA Paolo Cusano, Matteo de Marzo, Andrea Ferrari, 86 - EIGHTY SIX 1 9788834906170 € 6,50 MAGGIO Valentina Ghidini, Fabio Graziano, Eleonora 86 - EIGHTY SIX 2 9788834906545 € 6,50 GIUGNO Moscarini, Lucia Palombi, Valentina Andrea Sala, Federico Salvan, Marco Schiavone, Fabrizio Sesana DAISY JEALOUSY 9788834906507 € 7,50 GIUGNO DANMACHI - SWORD ORATORIA 17 9788834906552 € 5,90 GIUGNO UFFICIO COMMERCIALE DEATH STRANDING 1 9788834915455 € 12,50 GIUGNO tel. +39 02 36530450 DEATH STRANDING BOX VOL. 1-2 9788834915448 € 25,00 GIUGNO [email protected] DUNGEON FOOD 9 9788834906569 € 6,90 GIUGNO [email protected] GOBLIN SLAYER 10 9788834906576 € 6,50 GIUGNO [email protected] GOLDEN KAMUI 23 9788834906583 € 6,90 GIUGNO DISTRIBUZIONE IN FUMETTERIE GUNDAM UNICORN 15 9788834906590 € 6,90 GIUGNO Manicomix Distribuzione HANAKO KUN 8 9788834906606 € 5,90 GIUGNO Via IV Novembre, 14 - 25010 - San Zeno Naviglio (BS) JUJIN OMEGAVERSE: REMNANT 2 9788834906682 € 6,90 GIUGNO www.manicomixdistribuzione.it KAKEGURUI 14 9788834906613 € 6,90 GIUGNO DISTRIBUZIONE IN LIBRERIE KASANE 7 9788834906620 € 6,90 GIUGNO A.L.I. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2015-2016 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 1, 2 and 3, 2016 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR EMANUEL AX, PIANO / , BOY SOLOIST / , SOPRANO / , BASS THE ALL UNIVERSITY CHOIR CHRISTINE HESTWOOD AND ROBERT PAGE, DIRECTORS / CHILDREN’S CHORUS / , DIRECTOR JOHANNES BRAHMS Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante IV. Allegretto grazioso Mr. Ax Intermission CARL ORFF “Fortuna imperatrix mundi” from Carmina Burana for Chorus and Orchestra LEONARD BERNSTEIN Chichester Psalms for Chorus, Boy Soloist and Orchestra I. Psalm 108, vs. 2 (Maestoso ma energico) — Psalm 100 (Allegro molto) II. Psalm 23 (Andante con moto, ma tranquillo) — Psalm 2, vs. 1-4 (Allegro feroce) — Meno come prima III. Prelude (Sostenuto molto) — Psalm 131 (Peacefully flowing) — Psalm 133, vs. 1 (Lento possibile) boy soloist GIUSEPPE VERDI Overture to La forza del destino GIUSEPPE VERDI “Te Deum” (No. 4) from Quattro Pezzi Sacri April 1-3, 2016, page 2 for Chorus and Orchestra soprano soloist ARRIGO BOITO Prologue to Mefistofele for Bass Solo, Chorus, Children’s Chorus and Orchestra bass soloist April 1-3, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA JOHANNES BRAHMS Born 7 May 1833 in Hamburg, Germany; died 3 April 1897 in Vienna, Austria Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 83 (1878, 1881) PREMIERE OF WORK: Budapest, 9 November 1881; Redoutensaal; Orchestra of the National Theater; Alexander Erkel, conductor; Johannes Brahms, soloist PSO PREMIERE: 15 January 1909; Carnegie Music Hall; Emil Paur, conductor and soloist APPROXIMATE DURATION: 50 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: woodwinds in pairs plus piccolo, four horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings In April 1878, Brahms journeyed to Goethe’s “land where the lemon trees bloom” with two friends, the Viennese surgeon Theodor Billroth and the composer Carl Goldmark. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Artxsr, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. Page(s) were microfilmed as received. 131,172 This reproduction is the best copy available UMI FRANK WEDEKIND’S FANTASY WORLD: A THEATER OF SEXUALITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Bv Stephanie E. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Manfred Lord Byron (1788–1824)

Manfred Lord Byron (1788–1824) Dramatis Personæ MANFRED CHAMOIS HUNTER ABBOT OF ST. MAURICE MANUEL HERMAN WITCH OF THE ALPS ARIMANES NEMESIS THE DESTINIES SPIRITS, ETC. The scene of the Drama is amongst the Higher Alps—partly in the Castle of Manfred, and partly in the Mountains. ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’ Act I Scene I MANFRED alone.—Scene, a Gothic Gallery. Time, Midnight. Manfred THE LAMP must be replenish’d, but even then It will not burn so long as I must watch. My slumbers—if I slumber—are not sleep, But a continuance of enduring thought, 5 Which then I can resist not: in my heart There is a vigil, and these eyes but close To look within; and yet I live, and bear The aspect and the form of breathing men. But grief should be the instructor of the wise; 10 Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth, The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life. Philosophy and science, and the springs Of wonder, and the wisdom of the world, 15 I have essay’d, and in my mind there is A power to make these subject to itself— But they avail not: I have done men good, And I have met with good even among men— But this avail’d not: I have had my foes, 20 And none have baffled, many fallen before me— But this avail’d not:—Good, or evil, life, Powers, passions, all I see in other beings, Have been to me as rain unto the sands, Since that all—nameless hour. -

"With His Blood He Wrote"

:LWK+LV%ORRG+H:URWH )XQFWLRQVRIWKH3DFW0RWLILQ)DXVWLDQ/LWHUDWXUH 2OH-RKDQ+ROJHUQHV Thesis for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD) at the University of Bergen 'DWHRIGHIHQFH0D\ © Copyright Ole Johan Holgernes The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Year: 2017 Title: “With his Blood he Wrote”. Functions of the Pact Motif in Faustian Literature. Author: Ole Johan Holgernes Print: AiT Bjerch AS / University of Bergen 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following for their respective roles in the creation of this doctoral dissertation: Professor Anders Kristian Strand, my supervisor, who has guided this study from its initial stages to final product with a combination of encouraging friendliness, uncompromising severity and dedicated thoroughness. Professor Emeritus Frank Baron from the University of Kansas, who encouraged me and engaged in inspiring discussion regarding his own extensive Faustbook research. Eve Rosenhaft and Helga Muellneritsch from the University of Liverpool, who have provided erudite insights on recent theories of materiality of writing, sign and indexicality. Doctor Julian Reidy from the Mann archives in Zürich, with apologies for my criticism of some of his work, for sharing his insights into the overall structure of Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, and for providing me with some sources that have been valuable to my work. Professor Erik Bjerck Hagen for help with updated Ibsen research, and for organizing the research group “History, Reception, Rhetoric”, which has provided a platform for presentations of works in progress. Professor Lars Sætre for his role in organizing the research school TBLR, for arranging a master class during the final phase of my work, and for friendly words of encouragement. -

Catalogo Catalogue 2019.Pdf

IN UN MONDO CHE CAMBIA, PUOI AMARE IL CINEMA FESTA DEL CINEMA DI ROMA DA UN’ALTRA PROSPETTIVA. 17-27 Ottobre 2019 PRODOTTO DA MAIN PARTNER Promosso da Partner Istituzionali Messaggio pubblicitario con finalità promozionale. WE LOVE CINEMA In collaborazione con BNL Main Partner della Festa del Cinema di Roma, dal 17 al 27 ottobre. Seguila da un altro punto di vista, su welovecinema.it e con la nostra app. by BNL - BNP PARIBAS welovecinema.it Sponsor Uffi ciali Auto Uffi ciale La banca per un mondo che cambia Partner Partner Tecnico Main Media Partner TV Uffi ciale Media Partner Sponsor FOOD PROMOTION & EVENTS MANAGEMENT Sponsor Tecnici PRODUZIONI E ALLESTIMENTI L'APP DELLA REGIONE LAZIO CON SCONTI E PROMOZIONI PER I GIOVANI DAI 14 AI 29 ANNI su cinema, eventi, libri, concerti, teatro, sport, turismo, pub e ristoranti SCARICA L’APP DAGLI STORE SCOPRI DI PIÙ NELLO SPAZIO DELLA REGIONE LAZIO ALLA FESTA AUDITORIUM PARCO DELLA MUSICA VIVILE STAGIONI DELLE ARTI CONCERTI FESTIVAL RASSEGNE VIALE PIETRO DE COUBERTIN • 00196 ROMA INFO: 06 8024 1281 • BIGLIETTERIA: 892 101 (SERVIZIO A PAGAMENTO) PROGRAMMAZIONE E BIGLIETTI SU AUDITORIUM.COM Siamo con il CINEMA ITALIANO ovunque voglia arrivare. cinecittaluce.it festadelcinema_165 X240 .indd 1 18/09/19 09:20 esecutivo-pagina-cinema.pdf 1 17/09/2019 09:47:37 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Lavoriamo ogni giorno per valorizzare il set più bello del mondo. Mazda CX-30 Cat FestaCinema 165x240.indd 1 01/10/19 10:13 SIAE_per_FestaCinemaRoma_2019_165x240.pdf 1 10/09/19 11:47 SOGNI IDEE ARTE EeMOZIONI 14A EDIZIONE | 14TH EDITION -

Product Guide

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE AFM AT YOUR FINGERTIPS – THE PDA CULTURE IS HAPPENING! THE FUTURE US NOW SOURCE - SELECT - DOWNLOAD©ONLY WHAT YOU NEED! WHEN YOU NEED IT! GET IT! SEND IT! FILE IT!© DO YOUR PART TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING In 1983 The Business of Film innovated the concept of The PRODUCT GUIDE. • In 1990 we innovated and introduced 10 days before the major2010 markets the Pre-Market PRODUCT GUIDE that synced to the first generation of PDA’s - Information On The Go. • 2010: The Internet has rapidly changed the way the film business is conducted worldwide. BUYERS are buying for multiple platforms and need an ever wider selection of Product. R-W-C-B to be launched at AFM 2010 is created and designed specifically for BUYERS & ACQUISITION Executives to Source that needed Product. • The AFM 2010 PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is published below by regions Europe – North America - Rest Of The World, (alphabetically by company). • The Unabridged Comprehensive PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH contains over 3000 titles from 190 countries available to download to your PDA/iPhone/iPad@ http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/Europe.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/NorthAmerica.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/RestWorld.doc The Business of Film Daily OnLine Editions AFM. To better access filmed entertainment product@AFM. This PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is divided into three territories: Europe- North Amerca and the Rest of the World Territory:EUROPEDiaries”), Ruta Gedmintas, Oliver -

Atti XXXI Convegno Giappone.Pdf

Associazione Italiana per gli Studi Giapponesi AISTUGIA ATTI DEL XXXI CONVEGNO DI STUDI SUL GIAPPONE Venezia, 20-22 settembre 2007 a cura di Rosa Caroli Presidente: Adriana Boscaro Segretario Generale: Corrado Molteni Consiglieri: Giorgio Amitrano Graziana Canova Rosa Caroli Teresa Ciapparoni Silvana De Maio Maria Chiara Migliore Revisori dei Conti: Simone Dalla Chiesa Franco Manni Emilia Scalise Probiviri: Carlo Filippini Gianfranco Fusco Aldo Tollini Sedi del Convegno: Auditorium Santa Margherita Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia Orientale, Palazzo Vendramin dei Carmini Gli Atti sono stati curati da Rosa Caroli, che desidera esprimere un caloroso ringraziamento ad Adriana Boscaro per i preziosi consigli, a Ikuko Sagiyama per la revisione dei testi in giapponese e a Valerio L. Alberizzi per la parte tecnica. Gli scritti impegnano solo la responsabilità degli autori. Copertina: Hideyoshi in Laguna © Andreina Parpajola Scritta giapponese del maestro calligrafo e professore dell’Università di Kanazawa: Miyashita Takaharu Sito web dell’Associazione: http://venus.unive.it/aistug Finito di stampare nel mese di aprile 2008 dalla Tipografia Cartotecnica Veneziana srl La realizzazione del XXXI Convegno AISTUGIA e la pubblicazione degli Atti relativi sono state rese possibili dal contributo di: Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia Orientale, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Regione del Veneto Toshiba International Foundation The Japan Foundation A questi enti dirigenti e soci dell’AISTUGIA esprimono la loro più viva gratitudine. Il XXXI Convegno AISTUGIA -

The Devil Himself

THE DEVIL HIMSELF: AN EXAMINATION OF REDEMPTION IN THE FAUST LEGENDS by KRISTEN S. RONEY (Under the Direction of Katharina M. Wilson) ABSTRACT Careful readers can see Faust everywhere; he continues to appear in film, in politics, and in various forms of popular culture. From Hrotsvit, to Spies, to Marlowe, Goethe, Mann, Mofolo and even Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, Faust is a fascinating subject because he is so human; the devil (in whatever form he takes— from poodle to bald androgyne) is representative of our desires—many of which we are fearful of expressing. He fascinates because he acts on the very desires we wish to repress and reveals the cultural milieu of desire in his damnation or redemption. It is from this angle that I propose to examine the Faust legends: redemption. Though this dissertation is, ideally, part of a much larger study on the redemption topoi in literature, Faust exemplifies the problems and definitions. Studied most often as a single text subject, say Goethe’s Faust or Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” redemption lacks significant research on its own grounds, despite it prevalence in literature, except where it is encoded within the discussion of the function of literature itself. I propose, instead, that Redemption has a four related, but separate, uses in literature and literary interpretation involving sacred, secular, political, and aesthetic redemptions. In order to elucidate the matter, I will use the Faust legends and the appearance of redemption within them. INDEX WORDS: Redemption, Faust, Rosemary’s Baby, Frankenstein, Manfred, Hrotsvit, Doctor Faustus, Mephisto, Aesthetics, Walter Benjamin, Penitential THE DEVIL HIMSELF: AN EXAMINATION OF REDEMPTION IN THE FAUST LEGENDS by KRISTEN S. -

Construction Law Update

THE MAGAZINE OF THE MASTER BUILDERS’ ASSOCIATION OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2019 CONSTRUCTION L AW UPDATE 19-09-06_PDP_Ad_BreakingGround.pdf 1 9/6/19 1:24 PM 11 Theaters 215 Restaurants 130 Retailers 300+ Free Events 47 Acres of Parks C M Y 1.9 Billion Invested(2009-2019) CM MY CY 5,270 Residents CMY K 1,700 Residential Units in Development 80,000 Business Professionals 2/3 City's Commercial This could be your Office Space finest moment. It’s everything you could ever want and everything you never knew you needed. From historic architecture and world-class amenities to unparalleled transit services and unrivaled views, it’s all right here in Downtown Pittsburgh. Elevate your business at dwntwnpgh.com Everything points you here. One business-critical issue can have a dramatic effect. TURNING OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS INTO RESULTS From project conception through financing to close out, Cohen & Grigsby’s Construction team represents clients at every stage of construction. Our team includes both experienced business counsel as well as trial lawyers who prepare and defend complex claims, litigate matters in a variety of venues, and defend our clients against regulatory enforcement and inspection citations. Our attorneys represent and advise construction managers, contractors, subcontractors, material and equipment suppliers, engineers, developers, owners, and financial institutions. Consult directly with senior partners. Profit from efficient representation. Experience a culture of performance. 412.297.4900 • www.cohenlaw.com C&G_Breaking Ground Ad_8.375x10.875_v4.indd 1 3/13/19 3:19 PM Quality. Excellence. Integrity. For 68 years, A. Martini & Co. has been providing construction management and general contracting expertise to meet your project needs. -

Art & Finance Report 2019

Art & Finance Report 2019 6th edition Se me Movió el Piso © Lina Sinisterra (2014) Collect on your Collection YOUR PARTNER IN ART FINANCING westendartbank.com RZ_WAB_Deloitte_print.indd 1 23.07.19 12:26 Power on your peace of mind D.KYC — Operational compliance delivered in managed services to the art and finance industry D.KYC (Deloitte Know Your Customer) is an integrated managed service that combines numerous KYC/AML/CTF* services, expertise, and workflow management. The service is supported by a multi-channel web-based platform and allows you to delegate the execution of predefined KYC/AML/CTF activities to Deloitte (Deloitte Solutions SàRL PSF, ISO27001 certified). www2.deloitte.com/lu/dkyc * KYC: Know Your Customer - AML/CTF: Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Empower your art activities Deloitte’s services within the Art & Finance ecosystem Deloitte Art & Finance assists financial institutions, art businesses, collectors and cultural stakeholders with their art-related activities. The Deloitte Art & Finance team has a passion for art and brings expertise in consulting, tax, audit and business intelligence to the global art market. www.deloitte-artandfinance.com © 2019 Deloitte Tax & Consulting dlawmember of the Deloitte Legal network The Art of Law DLaw – a law firm for the Art and Finance Industry At DLaw, a dedicated team of lawyers supports art collectors, dealers, auctioneers, museums, private banks and art investment funds at each stage of their project. www.dlaw.lu © 2019 dlaw Art & Finance Report 2019 | Table of contents Table of contents Foreword 14 Introduction 16 Methodology and limitations 17 External contributions 18 Deloitte CIS 21 Key report findings 2019 27 Priorities 31 The big picture: Art & Finance is an emerging industry 36 The role of Art & Finance within the cultural and creative sectors 40 Section 1.