Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goethe, the Japanese National Identity Through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989

Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik pen Jahrgang LI – Heft 1 | Peter Lang, Bern | S. 57–100 Goethe, the Japanese National Identity through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989 By Stefan Keppler-Tasaki and Seiko Tasaki, Tokyo Dedicated to A . Charles Muller on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Tokyo This is a study of the alleged “singular reception career”1 that Goethe experi- enced in Japan from 1889 to 1989, i. e., from the first translation of theMi gnon song to the last issues of the Neo Faust manga series . In its path, we will high- light six areas of discourse which concern the most prominent historical figures resp. figurations involved here: (1) the distinct academic schools of thought aligned with the topic “Goethe in Japan” since Kimura Kinji 木村謹治, (2) the tentative Japanification of Goethe by Thomas Mann and Gottfried Benn, (3) the recognition of the (un-)German classical writer in the circle of the Japanese national author Mori Ōgai 森鴎外, as well as Goethe’s rich resonances in (4) Japanese suicide ideals since the early days of Wertherism (Ueruteru-zumu ウェル テルヅム), (5) the Zen Buddhist theories of Nishida Kitarō 西田幾多郎 and D . T . Suzuki 鈴木大拙, and lastly (6) works of popular culture by Kurosawa Akira 黒澤明 and Tezuka Osamu 手塚治虫 . Critical appraisal of these source materials supports the thesis that the polite violence and interesting deceits of the discursive history of “Goethe, the Japanese” can mostly be traced back, other than to a form of speech in German-Japanese cultural diplomacy, to internal questions of Japanese national identity . -

Samuel Ramey

welcome to LOS i\Ilgeles upera http://www.losangelesopera.comlproduction/index.asp?... •• PURCHASE TICKETS • 2003/2004 SEASON LA AMNATION DE FAD T La damnation de Faust The damnation of Faust / Hector Berlioz Nicholas and In French with English Supertitles Ticket Information Alexandra Lucia di Samuel Ramey, Synopsis Lammermoor r-----------.., Program Notes Denyce Graves and Photo Gallery Orfeo ed Euridice Paul Groves star in a spectacular new Recital: production by Achim Ask an Expert Hei-Kyung Hong Forward to a Freyer with Kent Friend Recital: Cecilia Nagano conducting. Bartoli Generously Madama Europe's master Underwritten by: Butterfly theatre artist Achim Freyer matches his New production Die Frau ohne made possible by a Schatten painterly visual imagery with Hector generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Recital: Dmitri Berlioz's vivid musical imagination in the premiere of Hvorostovsky Milan Panic this new production featuring a cast of more than Le nozze di 100 singers and dancers. The legend of Faust, which Figaro tells the story of the man who sold his soul to the II trovatol'"e Devil, has captivated great imaginations for centuries. Marlowe, Goethe, Gounod, Schumann, Liszt, Mahler and Stravinsky all found inspiration in SEASON G!J1]) the Faust tale, which continues to reverberate in SPONSOR Audt today's modern world. Originally conceived as an oratoriO, Hector Berlioz's dramatic La damnation de Faust is now a mainstay of opera houses around the world. Haunting melodies and startling orchestrations flood the score and illustrate the beWitching tale of Faust's desperate struggle for power, riches, youth and, ultimately, redemption. PRODUCTION DATES: Wednesday September 10, 20036:30 p.m. -

Early Faust Literature and Skepticism in the Reformation

Dustin Lovett 20 Polemical Magic: Early Faust Literature and Skepticism in the Reformation Dustin Lovett (University of California, Santa Barbara) Richard Popkin’s epochal work on the history of skepticism in the Early Modern period1 identifies the seminal gesture of the Reformation, Luther’s rejection of the Catholic church’s entire framework of authority at the Diet of Worms, as the opening of a “Pandora’s Box” that sparked a skeptical crisis, or “crise pyrrhonienne,” which soon engulfed the Western world (5). Popkin’s narrow understanding of the term skepticism and his emphasis on the role of the printed Latin translations of Sextus Empiricus’s work in the 1560s in the birth of modern science have become controversial, but whether one adopts Popkin’s view of an acute crisis in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries or takes a longer and broader view of skepticism,2 the Reformation marks a moment of profound transformation in the history of European thought. As Stuart Clark notes, the temptation “to think of the [Early Modern] period as one of radical epistemological instability” does not exist without reason (1997, 257). In rejecting the authority of the pope and church councils, which had previously arbitrated the nature of truth, in favor of “what conscience is compelled to believe on reading Scripture” (Popkin 3) Luther was redefining the criteria for religious orthodoxy. For centuries, the Catholic church alone had defined the nature of and means of achieving theological principles such as grace or repentance. The spiritual confusion that resulted from Luther’s repudiation of numerous Catholic doctrines finds its reflection in many literary works of the time but perhaps nowhere more potently than in the legend of Faust, which emerged and developed in the early Reformation era into a vehicle for Luther’s radical skepticism toward Catholic doctrines ranging from intercession and repentance to the saints’ cults and miracles. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Artxsr, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. Page(s) were microfilmed as received. 131,172 This reproduction is the best copy available UMI FRANK WEDEKIND’S FANTASY WORLD: A THEATER OF SEXUALITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Bv Stephanie E. -

Eroe Byroniano E Confronto Tra Manfred E Faust

EROE BYRONIANO E CONFRONTO TRA MANFRED E FAUST Introduzione all’autore: George Gordon Byron è considerato da molti critici il poeta indiscusso della corrente romantica. Il suo spirito libero e ribelle, che condivide con il suo amico Shelley, la sua passione per l’occulto, che lo rendono un possibile esponente della scuola satanica dei poeti, il suo evidente approccio con la corrente gotica e con tutto ciò che si può definire sublime, lo rendono sicuramente l’esempio vivente della definizione “bello e dannato”. La sua deformità fisica e il suo amore impossibile per la moglie di suo cugino fanno di lui un uomo dalla complessa e misteriosa personalità. E’ infatti risaputo che la sua vita fu piena di scandali, a causa della sua natura passionale e cinica. Il suo stile è chiaro ed egli è molto attento alle forme, tuttavia dalle sue opere ne esce anche una vena satirica, il cui scopo è rendere pubblico il suo disprezzo per le regole della società, che rendono la sua scrittura un’apoteosi di sfaccettature per niente scontate che rispecchiano il suo carattere. Eroe Byroniano: Tutti i protagonisti delle opere di Byron vengono definiti “eroi byroniani” per la loro evidente somiglianza con l’autore; in alcuni casi non sarebbe sbagliato parlare anche di autobiografia. L’elemento che accomuna tutti i protagonisti è il tema della ribellione: gli eroi del racconto scappano da un passato oscuro, pieno di costrizioni e disagi di diversi tipi, che li portano inevitabilmente sulla via della perdizione. Il loro fascino attira le persone che li circondano, ma il disprezzo che provano per il mondo supera ogni tentativo di creare un legame con gli altri personaggi. -

La Forza Del Destino

LA FORZA DEL DESTINO versione del 1869 Melodramma in quattro atti. testi di Francesco Maria Piave Antonio Ghislanzoni musiche di Giuseppe Verdi Prima esecuzione: 27 febbraio 1869, Milano. www.librettidopera.it 1 / 55 Informazioni La forza del destino Cara lettrice, caro lettore, il sito internet www.librettidopera.it è dedicato ai libretti d©opera in lingua italiana. Non c©è un intento filologico, troppo complesso per essere trattato con le mie risorse: vi è invece un intento divulgativo, la volontà di far conoscere i vari aspetti di una parte della nostra cultura. Motivazioni per scrivere note di ringraziamento non mancano. Contributi e suggerimenti sono giunti da ogni dove, vien da dire «dagli Appennini alle Ande». Tutto questo aiuto mi ha dato e mi sta dando entusiasmo per continuare a migliorare e ampliare gli orizzonti di quest©impresa. Ringrazio quindi: chi mi ha dato consigli su grafica e impostazione del sito, chi ha svolto le operazioni di aggiornamento sul portale, tutti coloro che mettono a disposizione testi e materiali che riguardano la lirica, chi ha donato tempo, chi mi ha prestato hardware, chi mette a disposizione software di qualità a prezzi più che contenuti. Infine ringrazio la mia famiglia, per il tempo rubatole e dedicato a questa attività. I titoli vengono scelti in base a una serie di criteri: disponibilità del materiale, data della prima rappresentazione, autori di testi e musiche, importanza del testo nella storia della lirica, difficoltà di reperimento. A questo punto viene ampliata la varietà del materiale, e la sua affidabilità, tramite acquisti, ricerche in biblioteca, su internet, donazione di materiali da parte di appassionati. -

Premiere LA FORZA DEL DESTINO (THE FORCE OF

Premiere LA FORZA DEL DESTINO (THE FORCE OF DESTINY) Opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave based on the play Don Àlvaro o La fuerza del sino (1835) by Ángel de Saaverda Sung in Italian with German and English surtitles Conductor: Jader Bignamini / Gaetano Soliman (May 2019) Director: Tobias Kratzer Set and Costume Designer: Rainer Sellmaier Video: Manuel Braun Lighting Designer: Joachim Klein Chorus Master: Tilman Michael Dramaturge: Konrad Kuhn Marchese di Calatrava / Padre Guardiano: Franz Josef Selig / Andreas Bauer Kanabas (May 2019) Donna Leonora: Michelle Bradley Don Carlo di Vargas: Christopher Maltman / Evez Abdulla (May 2019) Don Alvaro: Hovhannes Ayvazyan / Arsen Soghomonyan (May 2019) Prezosilla: Tanja Ariane Baumgartner / Judita Nagyová (February 7th, 9th, 15th, May 2019) Frau Melitone: Craig Colclough amongst others Oper Frankfurt's Chorus and Extras; Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester With generous support from the DZ Bank and the Frankfurt Patronatsverein – Sektion Oper The World Premiere of the 1st edition of La forza del destino (The Force of Destiny) by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) took place on November 10th 1862, a year later than planned, at the Bolshoi Theatre in St. Petersburg. The libretto for this four act opera, based on the play Don Álvaro o La fuerza del sino (1835) by Ángel de Saavedra, was written by Francesco Maria Piave. Apart from two concert performances at the Alte Oper in 2005, this is the first New Production in Frankfurt since 1974, now in the rarely performed unabridged Petersburg edition. Leonora, Marchese di Calatrava's daughter, loves the mestizo Don Alvaro, against her father's will. -

Investigating Italy's Past Through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and Tv

INVESTIGATING ITALY’S PAST THROUGH HISTORICAL CRIME FICTION, FILMS, AND TV SERIES Murder in the Age of Chaos B P ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES AND ITALIAN ITALIAN Italian and Italian American Studies Series Editor Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Hempstead , New York, USA Aims of the Series This series brings the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of spe- cialists, general readers, and students. Featuring works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices, it has been a longstanding force in shaping the evolving fi elds of Italian and Italian American Studies by re-emphasizing their connection to one another. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14835 Barbara Pezzotti Investigating Italy’s Past through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and TV Series Murder in the Age of Chaos Barbara Pezzotti Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand Italian and Italian American Studies ISBN 978-1-137-60310-4 ISBN 978-1-349-94908-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-349-94908-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948747 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

High-Fidelity-1980-1

S1.50 NOVEMBER 1980 HIGH FIDELIT HIGH-TECH RECORDS Are they worth them ey? Double - blindtests reveal the truth I e cg 111. AUDIO AT HOME N oon? How good? ^ .c 40' ooi'9 --- -1 o.ISTENING REPORTS Vssexy cassette deck y's "robot" turntable F...rs top -value receiver 11 it 01 0839E IF ALL $200TURNTABLES HAVE THE SAME SPECS, HOWCOME THE PL -400 SOUNDS BETTER? Il MEN -WPC IWO AL 4 MilmiiiiM . 1111111.1111111.11.1.111111111101 .TE Alzr 'T % 'I iv'.,.r I 1 1 IPATING 0 et.N\ qZ, r3lczbrowecont (= NS 4.0 VI, A _,.. joimma, 7 0,0 ;a! 11.111,, " "'".11"1"' The best for both worlds The culmination of 30 years of Audio Engineer- A fresh new breakthrough in cartridge de- ing leadership-the new Stereohedron velopment designed specifically as an answer for the low impedance moving coil cartridge- XSV/5000 XLZ/7500S One of the most dramatic developments of car- tridge performance was the introduction of the The advantages of the XLZ/7500S are that it offers - ,. Pickering XSV /3000. It offered the con- characteristics exceeding even the best of moving 'lila coil cartridges. Features such as an openness of sound and extremely fast risetime, less than 10µ, to provide a new crispness in sound reproduction. At the same tine, the XLZ/7500S provides these features without any of the disadvantages of ringing, undesirable spurious harmonics which are often characterizations of moving coil pickups. The above advantages provide a new sound experience while utilizing the proven advantages of the Stereohedron stylus, a samarium sumer a first 'generation of cartridges, combining 1.\\_ both high tracking ability and superb frequency response. -

01-11-2019 Aida Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI aida conductor Opera in four acts Nicola Luisotti Libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni production Sonja Frisell Friday, January 11, 2019 PM set designer 7:30–11:10 Gianni Quaranta costume designer Dada Saligeri lighting designer Gil Wechsler choreographer Alexei Ratmansky The production of Aida was made revival stage director Stephen Pickover possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Donald D. Harrington The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Viking Cruises general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,171st Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S aida conductor Nicola Luisotti in order of vocal appearance r amfis a priestess Vitalij Kowaljow Leah Hawkins** r adamès amonasro Yonghoon Lee Roberto Frontali amneris Dolora Zajick solo dancers Min-Tzu Li aida Brian Gephart Kristin Lewis the king Soloman Howard a messenger Arseny Yakovlev** Friday, January 11, 2019, 7:30–11:10PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Aida Musical Preparation Gareth Morrell, Howard Watkins*, Joshua Greene, and Bryan Wagorn* Assistant Stage Directors Jonathon Loy and J. Knighten Smit Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Joshua Greene Met Titles Christopher Bergen Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Headdresses by Rodney Gordon Studios and Miles-Laity, Ltd. Animals supervised by All-Tame Animals, Inc. This performance is made possible in part by public * Graduate of the funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. -

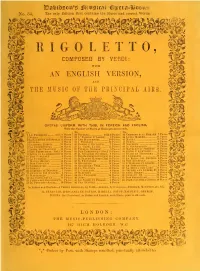

Rigoletto, Composes by Verdi: with an English Version, and the Music of the Principal Airs

No. 34. The only Edition that contains the Music and correct Words. RIGOLETTO, COMPOSES BY VERDI: WITH AN ENGLISH VERSION, AND THE MUSIC OF THE PRINCIPAL AIRS IjIBfipf l^g UNIFORM WITH THIS, IN FOREICN AND ENCLISH, With the Number of Pieces of Music printed in each. No. No. 1 Le Peophete with 9 Pieces 22 Fidklio with 5 Pieces 43 Crispino e la Comare 7 2 Noema 1- Pieces 23 L' Elisiee d'Amore 9 Pieces 44 Luisa Miller 14 3 IlBaebierediSivigliaH Pieces 24 Les Huguenots 10 Pieces 45 Marta 10 4 Otello 8 Pieces 25 I Puritani io Pieces 46 Zampa 8 5 Lucrezia Borgia 15 Pieces 20 Romeo e Giulietta 7 Pines 47 Macbeth 12 La Cekebbntola 10 Pieces 27 La Gazza Ladra 11 Pieces 48 II Giuramento 15 7 Linda di Chamouni ...10 Pieces 2S PiPEi.io (German) 5 Pieces 40 Matrimonio Segreto 10 8 Lek Fbeischtjtz (Hal.) 10 Pieces 2» Der FREiscnuiz (Ger.) lo Pieces 50 Orfeo e Eurydice 8 9 LUCIA DI LamMEEMOOR 10 Pieces so II Seraglio (German)... 7 Pieces > 51 Ballo in Maschera ...12 10 Don Pasquale 6 Pieces 31 Die Zaubeeflote (Ger) 10 Pieces ! 52 I Lombardi 14 11 La Favorita 8 Pieces 32 II Flauto Magico (Ita) 10 Pieces 63 La Forza del Destino 9 12 Medea (Mayer) 10 Pieces 33 II Trovatore 16 Pieces 64 Don Bucefalo 4 18 ]>cm Giovanni 11 Pieces 34, KlGOLETTO 10 Pieces 55 L'Italiana in Algeri... 8 | 50 Precauzioni 8 1 1 Semiramide 10 Pieces 35 Guglielmo Teli. 6 Pieces Le là Kunani 10 Pieces 30 La Traviata 12 Pieces 57 La Donna del Lago ...li Pieces I 8 Pieces 58 Orphee aux Enfees, Fr 9 l'ieres 16 Koiikkto II Diavolo ..