Divination in the Works of the Shishuo (A New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Dahai Dahai Beile About 1626

Dahai Dahai beile about 1626. Dudu took part in several translations in 1630 he was given a minor heredi campaigns of the T'ien-ts'ung period (1627~36) tary rank, being the first of the non-military and also participated in the civil administration. officials ever to be so honored. In the following In 1636 he was made a prince of the third degree year he was given the title, baksi, or "teacher". with the designation, An-p'ing :t(2Ji .ft:fb. Dahai systematized the Manchu written Dudu's eldest son, Durhu tf:fiJij (1615~1655), language, classifying the words according to was also a prince of the third degree. A descend Mongol practice under twelve types of opening ant of Durhu, named Kuang-yu J't~ (T.fa.J[, syllables C+---*UJt shih-er tzu-t'ou). These d. 1900), was posthumously given the rank of a types were differentiated according as they prince of the fourth degree after he committed ended in a simple vowel, a diphthong in i (ai, suicide in 1900 when Peking fell to the Allies. ui, etc.), a diphthong in o (ao, eo etc.), or in A grandson of Dudu, named Sunu [q. v.], was one of the nine consonants, r, n, ng, k, s, t, b, l, converted to the Catholic faith. and m. In 1632, with the encouragement of Abahai [q. v.], he made some improvements in [1/222/1a; 2/3/12b; Ch'ing T'ai-tsu Wu-huang-ti the Manchu writing which had been borrowed shih-lu (see under Nurhaci); *~.:E-*~*-1 from the Mongol in 1599. -

Bibliographie

Bibliographie 1. Das Schrifttum von Wu Leichuan WU LEI-CH’UAN bzw. WU CHEN-CH’UN (WU ZHENCHUN), Pseudonym HUAI XIN Die englischen Titel in Klammern stammen aus den Originalausgaben, wo sich oft (aber nicht immer) ein chinesisches und ein englisches Inhaltsverzeichnis findet. Die Numerierung und Paginierung von SM, ZL und ZLYSM ist in den Originalausgaben, die dem Verfasser nur in Kopien vorlagen, nicht konsistent und oft nur schwer les- bar. Die Beiträge sind chronologisch geordnet. 1918 „Shu xin“ , in: Zhonghua jidujiaohui nianjian 5 (1918), S. 217-221. 1920 „Lizhi yu jidujiao“ (Confucian Rites and Christianity), in: SM 1 (1920), No. 2, S. 1-6. 1920 „Wo duiyu jidujiaohui de ganxiang“ (Problems of the Christian Church in China. A Statement of Religious Experience), in: SM 1 (1920), No. 4, S. 1-4. 1920 „Wo yong hefa du shengjing? Wo weihe du shengjing?“ , in: SM 1 (1920), No. 6, S. 1. 1920 „Wo suo xinyang de Yesu Jidu“ , in: SM 1 (1920), No. 9 und 10. 1921 „What the Chinese Are Thinking about Christianity“. Transl. by T.C. Chao, in: CR (February 1921), S. 97-102. 1923 „Jidujiao jing yu rujiao jing“ , in: SM 3 (1923), No. 6, S. 1- 6. Abgedruckt in Zhang Xiping und Zhuo Xinping (Hrsg.) 1999, S. 459-465. 1923 „Wo geren de zongjiao jingyan“ (My Personal Religious Experience), in: SM 3 (1923), No. 7-8, S. 1-3. 1923 „Lun Zhongguo jidujiaohui de qiantu“ , in: ZL 10. Juni 1923, No. 11. Abgedruckt in Zhang Xiping und Zhuo Xinping (Hrsg.) 1999, S. 333-336. 1923 „Jidutu jiuguo“ , in: ZL 1 (1923), No. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Ziran: Authenticity Or Authority?

religions Article Ziran: Authenticity or Authority? Misha Tadd Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 5 Jianguo Inner St., Dongcheng District, Beijing 100022, China; [email protected] Received: 26 December 2018; Accepted: 14 March 2019; Published: 18 March 2019 Abstract: This essay explores the core Daoist concept of ziran (commonly translated as spontaneity, naturalness, or self-so) and its relationship to authenticity and authority. Modern scholarship has often followed the interpretation of Guo Xiang (d. 312) in taking ziran as spontaneous individual authenticity completely unreliant on any external authority. This form of Daoism emphasizes natural transformations and egalitarian society. Here, the author draws on Heshanggong’s Commentary on the Daodejing to reveal a drastically dissimilar ziran conception based on the authority of the transcendent Way. The logic of this contrasting view of classical Daoism results not only in a vision of hierarchical society, but one where the ultimate state of human ziran becomes immortality. Expanding our sense of the Daodejing, this cosmology of authority helps unearths greater continuity of the text with Daoism’s later religious forms. Keywords: Heshanggong; Guo Xiang; ziran; authenticity; authority; transcendence; hierarchy; immortality 1. Introduction Ziran stands as one of the key pillars of Daoist philosophy, and, following the immensely influential theory of Guo Xiang (d. 312), has, in modern times, mostly been viewed as the spontaneous and natural “authenticity” -

Tao Yuanming's Perspectives on Life As Reflected in His Poems on History

Journal of chinese humanities 6 (2020) 235–258 brill.com/joch Tao Yuanming’s Perspectives on Life as Reflected in His Poems on History Zhang Yue 張月 Associate Professor of Department of Chinese Language and Literature, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, China [email protected] Abstract Studies on Tao Yuanming have often focused on his personality, reclusive life, and pas- toral poetry. However, Tao’s extant oeuvre includes a large number of poems on history. This article aims to complement current scholarship by exploring his viewpoints on life through a close reading of his poems on history. His poems on history are a key to Tao’s perspectives with regard to the factors that decide a successful political career, the best way to cope with difficulties and frustrations, and the situations in which literati should withdraw from public life. Examining his positions reveals the connec- tions between these different aspects. These poems express Tao’s perspectives on life, as informed by his historical predecessors and philosophical beliefs, and as developed through his own life experience and efforts at poetic composition. Keywords Tao Yuanming – poems on history – perspectives on life Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 [ca. 365–427], a native of Xunyang 潯陽 (contem- porary Jiujiang 九江, Jiangxi), is one of the best-known and most-studied Chinese poets from before the Tang [618–907]. His extant corpus, comprising 125 poems and 12 prose works, is one of the few complete collections to survive from early medieval China, largely thanks to Xiao Tong 蕭統 [501–531], a prince of the Liang dynasty [502–557], who collected Tao’s works, wrote a preface, and © ZHANG YUE, 2021 | doi:10.1163/23521341-12340102 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

DT-S PDM LN199-91 Chinese China Trends of Qigong Research At

Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 DEf:'-ENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY WASHINGTON. O. C. 20301 TRANSLA TION REQUESTER TRANSLATOR'S INITIALS TRANSLATION NUMBER F.NCLlS) TO I R NO. DT-S PDM LN199-91 LANGUAGE GEOGRAPHIC AREA (11 dlflerent t,om place ot publl chinese China ENGLISH TITLE OF TRANSLATION AGE NOS. TRANSLATED FROM ORIG DOC. Trends of Qigong Research at Home the paat ten years 22 pages FOREIGN TITLE OF TRANSLATION SG6A AUTHOR IS) FOREIGN TITLE OF DOCUMENT (Complete only if dif{erent Irom title 01 translation) Bejing TImmunity Research Center. Beijing PUBLISHER DATE AND PLACE OF PUBLICATION COMMENTS TRANSLATION DIA FORM Almr-AM ease 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 Trends of Qigong Research at Home and Abroad in the Past Ten Years Beijing Immunity Research Center, Beijing. Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 LN199-91 Trends of Qigong Research at Home and Abroad in the Past Ten Years Development of Qi9:on!l-.!.~,:!g"!~~".J:llHt~~p~,s.t ten years from 1_~.29 to 1988 ha§__ ~~~__ :t::l_l}p'!,~9..edented l.n Ql.gong history. -

This Entire Document

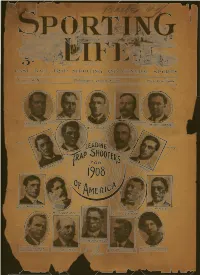

BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS Volume 50, No. 17. Philadelphia, January 4, 1908. Price, Five Cents. __/ ^^-p^BS^^ / 5CMPOWCRS i GFOMMAXWELL ANTJAAY 4, I9O8J for illegally conducting a saloon in this catcher Cliff Blank/fenship, of the Washing city. "Breit" was taken into custody on ton Club, up for a like period. This is food December 23 by the sheriff. He was re enough for thought! and ball men are frank leased immediately on his own recognizance, to admit that there will be trouble ahead but will have to stand trial. Breitenstein if the Pacific Coast League directors are has been conducting a thirst emporium not up and doing. Some months ago it was here since the Southern League season reported that the (putlaw league was gradu NEW YORK STATE LEAGUE©S closed. He was warned two or three times ally growing. It looks now as though the by friends that he was placing himself in a time is fast arriving when the National NEXT MEET, precarious position by not heeding the Commission will Have to take a most de laws of the state, but refused to be warned. cisive stand or else the -Coast League will His arrest followed. He realizes now that be forced to abandon organized ball and go he is in bad and said today that if he got back to outlawry. The Disposition of the A* J* G* out of this scrajpe he would certainly lead The National Commission Unani the simple life in the future. He is going to play ball in New Orleans again next sea THE XRI-STATE LEAGUE Franchise the Important Matter son, but hasn©t signed his contract as yet. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Chapter 5 Tang and the First Turkish Empire: From Appeasement to Conquest After the siege at Yanmen, Sui was on the verge of total collapse. A series of internal rebellions quickly turned into a turbulent civil war pit ting members of the ruling class against each other, and with different parts of the country under the control of local Sui generals sometimes facing rebel leaders, all of them soon contending for the greatest of all Chinese political prizes, the chance to replace a dynasty which had evi dently lost the Mandate. Those nearest the northern frontier naturally sought the support of the Eastern Turks, just as Turkish leaders had sought Chinese eissistance in their own power struggles.^ Freed of interference from a strong Chinese power, both the East ern and Western Turkish qaghanates soon recovered their positions of dominance in their respective regions. The Eastern qaghanate under Shibi Qaghan expanded to bring into its sphere of influence the Khitan and Shi- wei in the east and the Tuyuhun and Gaochang in the west. The Western Turks again expandedall the way to Persia, incorporating the Tiele and the various oasis states in the Western Regions, which one after another be came their subjects, paying regular taxes to the Western Turks. After an initial period of appeasement, Tang succeeded in conquer ing the Eastern Turks in 630 and the Western Turks in 659. This chapter examines the reasons for Tang’s military success, and how Tang tried to bring the Turks under Chinese administration so as to build a genuinely universal empire. -

Medical History Hare-Lip Surgery in the History Of

Medical History http://journals.cambridge.org/MDH Additional services for Medical History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine Kan-Wen Ma Medical History / Volume 44 / Issue 04 / October 2000, pp 489 - 512 DOI: 10.1017/S0025727300067090, Published online: 16 November 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0025727300067090 How to cite this article: Kan-Wen Ma (2000). Hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine. Medical History, 44, pp 489-512 doi:10.1017/S0025727300067090 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MDH, IP address: 144.82.107.82 on 08 Nov 2013 Medical History, 2000, 44: 489-512 Hare-Lip Surgery in the History of Traditional Chinese Medicine KAN-WEN MA* There have been a few articles published in Chinese and English on hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine. They are brief and some of them are inaccurate, although two recent English articles on this subject have presented an adequate picture on some aspects.' This article offers unreported information and evidence of both congenital and traumatic hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine and also clarifies and corrects some of the facts and mistakes that have appeared in works previously published either in Chinese or English. Descriptions of Hare-Lip and its Treatment in Non-Medical Literature The earliest record of hare-lip in ancient China with an imaginary explanation for its cause is found in jtk Huainan Zi, a book attributed to Liu An (179-122 BC).