New Migration Realities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framing Through Names and Titles in German

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4924–4932 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Doctor Who? Framing Through Names and Titles in German Esther van den Berg∗z, Katharina Korfhagey, Josef Ruppenhofer∗z, Michael Wiegand∗ and Katja Markert∗y ∗Leibniz ScienceCampus, Heidelberg/Mannheim, Germany yInstitute of Computational Linguistics, Heidelberg University, Germany zInstitute for German Language, Mannheim, Germany fvdberg|korfhage|[email protected] fruppenhofer|[email protected] Abstract Entity framing is the selection of aspects of an entity to promote a particular viewpoint towards that entity. We investigate entity framing of political figures through the use of names and titles in German online discourse, enhancing current research in entity framing through titling and naming that concentrates on English only. We collect tweets that mention prominent German politicians and annotate them for stance. We find that the formality of naming in these tweets correlates positively with their stance. This confirms sociolinguistic observations that naming and titling can have a status-indicating function and suggests that this function is dominant in German tweets mentioning political figures. We also find that this status-indicating function is much weaker in tweets from users that are politically left-leaning than in tweets by right-leaning users. This is in line with observations from moral psychology that left-leaning and right-leaning users assign different importance to maintaining social hierarchies. Keywords: framing, naming, Twitter, German, stance, sentiment, social media 1. Introduction An interesting language to contrast with English in terms of naming and titling is German. -

Migrants & City-Making

MIGRANTS & CITY-MAKING This page intentionally left blank MIGRANTS & CITY-MAKING Dispossession, Displacement, and Urban Regeneration Ayşe Çağlar and Nina Glick Schiller Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Typeset in Minion and Trade Gothic type by BW&A Books, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Çaglar, Ayse, author. | Schiller, Nina Glick, author. Title: Migrants and city-making : multiscalar perspectives on dispossession / Ayse Çaglar and Nina Glick Schiller. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018004045 (print) | lccn 2018008084 (ebook) | isbn 9780822372011 (ebook) | isbn 9780822370444 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isbn 9780822370567 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh : Emigration and immigration—Social aspects. | Immigrants—Turkey—Mardin. | Immigrants— New Hampshire—Manchester. | Immigrants—Germany— Halle an der Saale. | City planning—Turkey—Mardin. | City planning—New Hampshire—Manchester. | City planning—Germany—Halle an der Saale. Classification: lcc jv6225 (ebook) | lcc jv6225 .S564 2018 (print) | ddc 305.9/06912091732—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004045 Cover art: Multimedia Center, Halle Saale. Photo: Alexander Schieberle, www.alexschieberle.de To our mothers and fathers, Sitare and Adnan Şimşek and Evelyn and Morris Barnett, who understood the importance of having daughters who -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 228. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 7. Mai 2021 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Änderungsantrag der Abgeordneten Christian Kühn (Tübingen), Daniela Wagner, Britta Haßelmann, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN zu der zweiten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Drs. 19/24838, 19/26023, 19/29396 und 19/29409 Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Mobilisierung von Bauland (Baulandmobilisierungsgesetz) Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 611 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 98 Ja-Stimmen: 114 Nein-Stimmen: 431 Enthaltungen: 66 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 07.05.2021 Beginn: 12:25 Ende: 12:57 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Dr. Michael von Abercron X Stephan Albani X Norbert Maria Altenkamp X Peter Altmaier X Philipp Amthor X Artur Auernhammer X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Melanie Bernstein X Christoph Bernstiel X Peter Beyer X Marc Biadacz X Steffen Bilger X Peter Bleser X Norbert Brackmann X Michael Brand (Fulda) X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Dr. Helge Braun X Silvia Breher X Sebastian Brehm X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Dr. Carsten Brodesser X Gitta Connemann X Astrid Damerow X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Thomas Erndl X Dr. Dr. h. c. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Enak Ferlemann X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Thorsten Frei X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Maika Friemann-Jennert X Michael Frieser X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. -

Uef-Spinelli Group

UEF-SPINELLI GROUP MANIFESTO 9 MAY 2021 At watershed moments in history, communities need to adapt their institutions to avoid sliding into irreversible decline, thus equipping themselves to govern new circumstances. After the end of the Cold War the European Union, with the creation of the monetary Union, took a first crucial step towards adapting its institutions; but it was unable to agree on a true fiscal and social policy for the Euro. Later, the Lisbon Treaty strengthened the legislative role of the European Parliament, but again failed to create a strong economic and political union in order to complete the Euro. Resulting from that, the EU was not equipped to react effectively to the first major challenges and crises of the XXI century: the financial crash of 2008, the migration flows of 2015- 2016, the rise of national populism, and the 2016 Brexit referendum. This failure also resulted in a strengthening of the role of national governments — as shown, for example, by the current excessive concentration of power within the European Council, whose actions are blocked by opposing national vetoes —, and in the EU’s chronic inability to develop a common foreign policy capable of promoting Europe’s common strategic interests. Now, however, the tune has changed. In the face of an unprecedented public health crisis and the corresponding collapse of its economies, Europe has reacted with unity and resolve, indicating the way forward for the future of European integration: it laid the foundations by starting with an unprecedented common vaccination strategy, for a “Europe of Health”, and unveiled a recovery plan which will be financed by shared borrowing and repaid by revenue from new EU taxes levied on the digital and financial giants and on polluting industries. -

Abgeordnete Bundestag Ergebnisse

Recherche vom 27. September 2013 Abgeordnete mit Migrationshintergrund im 18. Deutschen Bundestag Recherche wurde am 15. Oktober 2013 aktualisiert WWW.MEDIENDIENST-INTEGRATION.DE Bundestagskandidaten mit Migrationshintergrund VIELFALT IM DEUTSCHEN BUNDESTAG ERGEBNISSE für die 18. Wahlperiode Im neuen Bundestag finden sich 37 Parlamentarier mit eigener Migrationserfahrung oder mindestens einem Elternteil, das eingewandert ist. Im Verhältnis zu den insgesamt 631 Sitzen im Parlament stammen somit 5,9 Prozent der Abgeordneten aus Einwandererfamilien. In der gesamten Bevölkerung liegt ihr Anteil mehr als dreimal so hoch, bei rund 19 Prozent. In der vorigen Legislaturperiode saßen im Bundestag noch 21 Abgeordnete aus den verschiedenen Parteien, denen statistisch ein Migrationshintergrund zugesprochen werden konnte. Im Vergleich zu den 622 Abgeordneten lag ihr Anteil damals lediglich bei 3,4 Prozent. Die Anzahl der Parlamentarier mit familiären Bezügen in die Türkei ist von fünf auf elf gestiegen. Mit Cemile Giousouf ist erstmals auch in der CDU eine Abgeordnete mit türkischen Wurzeln im Bundestag vertreten, ebenso wie erstmals zwei afrodeutsche Politiker im Parlament sitzen (Karamba Diaby, SPD und Charles M. Huber, CDU). Gemessen an der Anzahl ihrer Sitze im Parlament verzeichnen die LInken mit 12,5 Prozent und die Grünen mit 11,1 Prozent den höchsten Anteil von Abgeordneten mit Migrationshintergrund. Die SPD ist mit 13 Parlamentariern in reellen Zahlen Spitzenreiter, liegt jedoch im Verhältnis zur Gesamtzahl ihrer Abgeordneten (193) mit 6,7 -

Daniela Kolbe Monika Lazar Jens Lehmann Sören Pellmann Mitglied Des Bundestages Mitglied Des Bundestages Mitglied Des Bundestages Mitglied Des Bundestages

Daniela Kolbe Monika Lazar Jens Lehmann Sören Pellmann Mitglied des Bundestages Mitglied des Bundestages Mitglied des Bundestages Mitglied des Bundestages Landesdirektion Sachsen Referat 32 Planfeststellung Altchemnitzer Straße 41 09120 Chemnitz Leipzig, 27.01.2021 Eingabe – Planfeststellungsverfahrens für das Vorhaben „Ausbau des Verkehrsflughafens Leipzig/Halle, Start- und Landebahn Süd mit Vorfeld“ 15. Änderung Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, seit vielen Jahren begleiten wir – ausgehend von der Petition Nr. 1-18-12-962-004760 und verschiedener Initiativen des Leipziger Stadtrates – Bürgerinnen und Bürger, die sich für eine starke Einschränkung der sogenannten „kurzen Südabkurvung“ einsetzen. Die im Rahmen der geplanten Änderung des Planfeststellungsverfahrens zum Ausbau des Flughafens Leipzig/Halle durch uns realisierten Gespräche und durchgeführte Korrespondenz u. a. mit dem sächsischen Wirtschaftsminister, Herrn Martin Dulig sowie dem Leiter der sächsischen Staatskanzlei, Herrn Oliver Schenk, signalisierten uns, dass es denkbar wäre, dass die Route „Kurze Südabkurvung“ mit den früher angedachten Beschränkungen von maximal 30 Tonnen tagsüber beflogen werden wird. Aus der Antragstellung im aktuellen geänderten Planfeststellungsverfahren ist neben anderen Flugrouten die „Kurze Südabkurvung“ enthalten, jedoch ohne der Empfehlung und den Vorgaben aus dem Ersten Planfeststellungsverfahren, die Flugroute „Kurze Südabkurvung“ auf Flugzeuge mit einem maximalen Abfluggewicht von 30 Tonnen und Flugzeiten tagsüber zu beschränken, zu folgen. Mit -

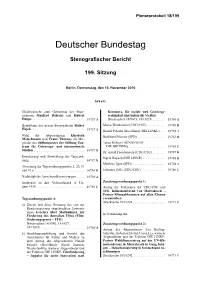

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Mitglieder Der SPD-Fraktion Im Deutschen Bundestag Sehr Geehrte

Mitglieder der SPD-Fraktion im Deutschen Bundestag Prof. Dr. Lars Castellucci, MdB, Platz der Republik 1, 11011 Berlin Bundeskanzlerin Frau Dr. Angela Merkel E-Mail Berlin, 11. September 2020 Sehr geehrte Frau Bundeskanzlerin, Prof. Dr. Lars Castellucci, MdB Platz der Republik 1 die Situation der Geflüchteten in Griechenland ist seit Monaten ka- 11011 Berlin tastrophal. Mit dem Brand im Lager Moria ist nun eine noch drama- Büro: Paul-Löbe-Haus Raum: 5.332 tischere humanitäre Katastrophe eingetreten. Es ist unsere gemein- Telefon: +49 30 227-73490 same europäische Verantwortung, endlich für menschenwürdige Fax: +49 30 227-76491 [email protected] Bedingungen an unseren Außengrenzen zu sorgen und nun vor al- lem schnell in der Not zu helfen. Wir begrüßen die Zusagen aus Prof. Dr. Lars Castellucci, MdB Deutschland für humanitäre Hilfe und die Entsendung des THW. Marktstraße 11 69168 Wiesloch Der Aufbau von provisorischen Unterbringungen vor Ort, ohne die Telefon: +49 6222-9399506 in Not lebenden Menschen aufs griechische Festland und in die EU [email protected] zu evakuieren, birgt jedoch die große Gefahr, dass sich erneut pre- käre Strukturen des Elends bilden. Vor allem aber die bisherigen Zusagen Deutschlands zur Aufnahme von Geflüchteten sind bestür- zend gering. Der Bundesinnenminister hat heute verkündet, dass Deutschland 150 Minderjährige aus Moria aufnehmen wird. Diese Größenord- nung ist der Lage nicht angemessen und beschämend. Länder und Kommunen haben bereits deutlich mehr Hilfe angeboten. Wir plä- dieren nachdrücklich dafür, dass Deutschland umgehend in der Größenordnung Geflüchtete aufnimmt, wie bereits Zusagen aus den Ländern vorliegen. Auch der Bundesminister für wirtschaftliche Zu- sammenarbeit hat sich für ein deutlich größeres Kontingent ausge- sprochen. -

Free PDF Download

DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATION D+ C ENTWICKLUNG UND ZUSAMMENARBEIT E +Z International Journal ISSN 2366-7257 D +CMONTHLY E-PAPER November 2017 ROHINGYA COOPERATION CLIMATE CHANGE Global silence Why India is How climate-smart in view of an important agriculture can genocidal action partner provide solutions Colonial legacy Title: Depiction of a slave ship: wood engraving from 1875. Photo: akg-images/Lineair D+C NOVEMBER 2017 In German in E+Z Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit. Both language versions FOCUS at www.DandC.eu Colonial legacy Monitor Consequences of the past Gates Foundation promotes Sustainable Development Goals with new report series | The division of Africa by European colonial ONE regards quality of aid in danger despite record ODA level | Cocoa industry powers had long-lasting consequences. They under pressure | Refugees increase water demand | Nowadays: Women’s issues in are manifested in today’s political systems, in Ugandan media | Imprint 4 economic dependencies and linguistic divi- sions. However, Africans themselves have to overcome the hurdles left by colonial rule, Debate says Jonathan Bashi, a law professor and con- sultant in the Democratic Republic of the Comments on the Rohingya’s exodus from Myanmar, Africa’s garment industry and the Congo. In West Africa, French troops help stabi- superiority of democracy over dictatorship plus a letter to the editor responding to a lise the region, explains Mohamed Gueye, a contribution by Ndongo Samba Sylla in our October e-Paper 10 Senegalese journalist. PAGES 24, 27 Compensation for former injustice Tribune HANS-JOCHEN LUHMANN At the beginning of the 20th century, German Relevant reading on the status of global climate policy beyond the Paris agreement 14 soldiers in the colony German South West Africa, which is today’s Namibia, committed a genocide. -

STIMMZETTEL Für Die Wahl Zum Deutschen Bundestag Im Wahlkreis 162 Chemnitz Am 24

STIMMZETTEL für die Wahl zum Deutschen Bundestag im Wahlkreis 162 Chemnitz am 24. September 2017 Sie haben 2 Stimmen hier 1 Stimme hier 1 Stimme für die Wahl für die Wahl einer/eines Wahlkreisabgeordneten einer Landesliste (Partei) - maßgebende Stimme für die Verteilung der Sitze insgesamt auf die einzelnen Parteien - Erststimme Zweitstimme 1 Heinrich, Frank Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands 1 Theologe CDU Dr. Thomas de Maizière, Arnold Vaatz, Chemnitz Christlich Demokratische Katharina Landgraf, Yvonne Magwas, Carsten Körber CDU Union Deutschlands 2 Leutert, Michael Gerhard DIE LINKE 2 Diplom-Soziologe DIE LINKE Katja Kipping, Dr. André Hahn, Caren Chemnitz Nicole Lay, Michael Gerhard Leutert, Sabine Zimmermann DIE LINKE DIE LINKE 3 Müller, Detlef Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands 3 Lokomotivführer SPD Daniela Kolbe, Thomas Edmund Jurk, Chemnitz Sozialdemokratische Partei Susann Rüthrich, Detlef Müller, Dr. Simone Raatz SPD Deutschlands 4 Köhler, Nico Alternative für Deutschland 4 selbstständig AfD Dr. Frauke Petry, Jens Maier, Siegbert Chemnitz Droese, Detlev Spangenberg, Tino Chrupalla AfD Alternative für Deutschland 5 Roden, Meike BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 5 Masterstudentin Psychologie GRÜNE Monika Lazar, Stephan Kühn, Meike Chemnitz BÜNDNIS 90/ Roden, Wolfgang Wetzel, Ines Kummer GRÜNE DIE GRÜNEN Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands 6 NPD Jens Baur, Arne Wolfgang Schimmer, Ines Schreiber, Jürgen Gansel, Dr. Johannes Müller 7 Müller-Rosentritt, Frank Freie Demokratische Partei 7 Diplom-Betriebswirt FDP Torsten Herbst, -

Kopfbögen Büro Bosbach

Wer sitzt eigentlich im Bundestag? Die Abgeordneten des 18. Deutschen Bun- destages Bei formaler Betrachtung ist die Lage folgende: Auf Grundlage einer personalisierten Verhältniswahl werden in 299 Wahlkreisen – von Wahlkreis 001 Flensburg-Schleswig, über meinen Wahlkreis 100, den Rheinisch-Bergischen Kreis, bis zum Wahlkreis 299 Homburg/Saar – die Mitglieder des Bundestages in allgemeiner, unmittelbarer, freier, gleicher und geheimer Wahl gewählt. Unter Berücksichtigung der 33 Überhang- und Ausgleichsmandaten gibt es im Bundestag derzeit 631 Abgeordnete – 230 Frauen und 401 Männer. Die Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages (kurz: MdB) repräsentieren Deutschland aber nicht nur in regionaler, sondern auch in kultureller und gesellschaftlicher Hinsicht. So gibt es viele Abgeordnete mit eigener Migrationserfahrung oder mindestens einem Elternteil, der eingewandert ist. Erstmals seit dieser Legislaturperiode sitzen zwei af- rodeutsche Politiker im Parlament: Dr. Karamba Diaby (SPD) und Charles M. Huber (CDU) – den meisten von Ihnen bekannt durch die TV-Krimi-Serie „Der Alte“. Ein Drittel der Abgeordneten sind 2013 neu ins Parlament gewählt worden. Weniger als ein Vier- tel vertreten ihren Wahlkreis oder die jeweilige Landesliste bereits ein zweites Mal. Für den Kollegen Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU) ist es nun sogar schon die 12. Wahlperi- ode – viele Jahre politischer Erfahrungen, die vor allem auch für die neueren Abgeord- neten eine besondere Hilfestellung bieten können. Derzeitiger Alterspräsident ist seit 2009 Dr. Heinz Riesenhuber (CDU). Traditionsgemäß hält er zu Beginn der neuen Wahlperiode die erste programmatische Rede. Demgegenüber tragen den Titel „jüngs- ter MdB“ Mahmut Özdemir (SPD) und Johannes Steiniger (CDU). Beide sind Jahrgang 1987 und damit mit erst 26 Jahren in den Bundestag eingezogen. Und auch die Berufe der Abgeordneten ergeben ein vielfältiges Bild: Neben Lehrern, Polizisten, Verwal- tungsmitarbeitern, Juristen, Volkswirten und Medizinern sind auch Unternehmer, Handwerker, Land- und Forstwirte, Auszubildende sowie Hausfrauen bzw. -

The Committees of the German Bundestag 2 3 Month in and Month Out, the German Bundestag Adopts New Laws Or Amends Existing Legislation

The Committees of the German Bundestag 2 3 Month in and month out, the German Bundestag adopts new laws or amends existing legislation. The Bundestag sets up permanent committees in every electoral term to assist it in accomplishing this task. In these committees, the Members concentrate on a specialised area of policy. They discuss the items referred to them by the ple- nary and draw up recommen- dations for decisions that serve as the basis for the ple- nary’s decision. The permanent committees of the German Bundestag – at the heart of Parliament’s work The Bundestag is largely free to decide how many commit- tees it establishes, a choice which depends on the priori- ties it wants to set in its par- liamentary work. There are 24 committees in the 19th electoral term. They essen- tially mirror the Federal Government’s distribution of ministerial portfolios, corre- sponding to the fields for which the ministries are The Committee on Labour and responsible. This facilitates Social Affairs and the Com- parliamentary scrutiny of the mittee on Internal Affairs and Federal Government’s work, Community have 46 members another of the Bundestag’s each, making them among the central functions. largest committees. Only the That said, in establishing com- Committee on Economic mittees, the Bundestag also Affairs and Energy has more sets political priorities of its members: 49. The Committee own. For example, the com- for the Scrutiny of Elections, mittees responsible for sport, Immunity and the Rules of tourism, or human rights and Procedure is the smallest humanitarian aid do not have committee, with 14 members.