From Freedom to Bondage: the Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

African Traditional Plant Knowledge in the Circum-Caribbean Region

Journal of Ethnobiology 23(2): 167-185 Fall/Winter 2003 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL PLANT KNOWLEDGE IN THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN REGION JUDITH A. CARNEY Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 ABSTRACT.—The African diaspora to the Americas was one of plants as well as people. European slavers provisioned their human cargoes with African and other Old World useful plants, which enabled their enslaved work force and free ma- roons to establish them in their gardens. Africans were additionally familiar with many Asian plants from earlier crop exchanges with the Indian subcontinent. Their efforts established these plants in the contemporary Caribbean plant corpus. The recognition of pantropical genera of value for food, medicine, and in the practice of syncretic religions also appears to have played an important role in survival, as they share similar uses among black populations in the Caribbean as well as tropical Africa. This paper, which focuses on the plants of the Old World tropics that became established with slavery in the Caribbean, seeks to illuminate the botanical legacy of Africans in the circum-Caribbean region. Key words: African diaspora, Caribbean, ethnobotany, slaves, plant introductions. RESUME.—La diaspora africaine aux Ameriques ne s'est pas limitee aux person- nes, elle a egalement affecte les plantes. Les traiteurs d'esclaves ajoutaient a leur cargaison humaine des plantes exploitables dAfrique et du vieux monde pour les faire cultiver dans leurs jardins par les esclaves ou les marrons libres. En outre les Africains connaissaient beaucoup de plantes dAsie grace a de precedents echanges de cultures avec le sous-continent indien. -

Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean

Integrated Country Strategy Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean FOR PUBLIC RELEASE FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Table of Contents 1. Chief of Mission Priorities ................................................................................................................ 2 2. Mission Strategic Framework .......................................................................................................... 3 3. Mission Goals and Objectives .......................................................................................................... 5 4. Management Objectives ................................................................................................................ 11 FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Approved: August 15, 2018 1 FOR PUBLIC RELEASE 1. Chief of Mission Priorities Our Mission is accredited bilaterally to seven Eastern Caribbean (EC) island nations (Antigua and Barbuda; Barbados; Dominica; Grenada; St. Kitts and Nevis; St. Lucia; and St. Vincent and the Grenadines) and to the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). All are English- speaking parliamentary democracies with stable political systems. All of the countries are also Small Island Developing States. The U.S. has close ties with these governments. They presently suffer from inherently weak economies, dependent on tourism, serious challenges from transnational crime, and a constant threat from natural disasters. For these reasons, our engagement focuses on these strategic challenges: Safety, Security, and Accountability for American Citizens and Interests Energy -

A Deductive Thematic Analysis of Jamaican Maroons

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sinclair-Maragh, Gaunette; Simpson, Shaniel Bernard Article — Published Version Heritage tourism and ethnic identity: A deductive thematic analysis of Jamaican Maroons Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing Suggested Citation: Sinclair-Maragh, Gaunette; Simpson, Shaniel Bernard (2021) : Heritage tourism and ethnic identity: A deductive thematic analysis of Jamaican Maroons, Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, ISSN 2529-1947, International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki, Vol. 7, Iss. 1, pp. 64-75, http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4521331 , https://www.jthsm.gr/?page_id=5317 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/230516 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, Vol. -

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

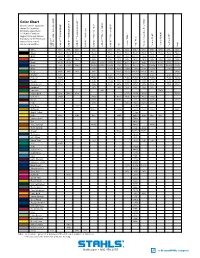

Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® Equivalent Shown

™ ™ II ® Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® equivalent shown. Due to printing limitations, colors shown 5807 Reflective ® ® ™ ® ® and Pantone numbers ® ™ suggested may vary from ac- ECONOPRINT GORILLA GRIP Fashion-REFLECT Reflective Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP ® ® ® ® ® ® ® tual colors. For the truest color ® representation, request Scotchlite our material swatches. ™ CAD-CUT 3M CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT Felt Perma-TWILL Poly-TWILL Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP Vinyl Pressure Sensitive Poly-TWILL Sensitive Pressure CAD-CUT White White White White White White White White White* White White White White White Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black* Black Black Black Black Black Gold 1235C 136C 137C 137C 123U 715C 1375C* 715C 137C 137C 116U Red 200C 200C 703C 186C 186C 201C 201C 201C* 201C 186C 186C 186C 200C Royal 295M 294M 7686C 2747C 7686C 280C 294C 294C* 294C 7686C 2758C 7686C 654C Navy 296C 2965C 7546C 5395M 5255C 5395M 276C 532C 532C* 532C 5395M 5255C 5395M 5395C Cool Gray Warm Gray Gray 7U 7539C 7539C 415U 7538C 7538C* 7538C 7539C 7539C 2C Kelly 3415C 341C 340C 349C 7733C 7733C 7733C* 7733C 349C 3415C Orange 179C 1595U 172C 172C 7597C 7597C 7597C* 7597C 172C 172C 173C Maroon 7645C 7645C 7645C Black 5C 7645C 7645C* 7645C 7645C 7645C 7449C Purple 2766C 7671C 7671C 669C 7680C 7680C* 7680C 7671C 7671C 2758U Dark Green 553C 553C 553C 447C 567C 567C* 567C 553C 553C 553C Cardinal 201C 188C 195C 195C* 195C 201C Emerald 348 7727C Vegas Gold 616C 7502U 872C 4515C 4515C 4515C 7553U Columbia 7682C 7682C 7459U 7462U 7462U* 7462U 7682C Brown Black 4C 4675C 412C 412C Black 4C 412U Pink 203C 5025C 5025C 5025C 203C Mid Blue 2747U 2945U Old Gold 1395C 7511C 7557C 7557C 1395C 126C Bright Yellow P 4-8C Maize 109C 130C 115U 7408C 7406C* 7406C 115U 137C Canyon Gold 7569C Tan 465U Texas Orange 7586C 7586C 7586C Tenn. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

Deborah Gochfield

DEBORAH JEAN GOCHFELD National Center for Natural Products Research P.O. Box 1848, University of Mississippi University, MS 38677-1848 Phone (662) 915-6769; Home (662) 281-0313 Fax: (662) 915-7062; Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. Zoology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii. Dec. 1997. Dissertation title: Mechanisms of coexistence between corals and coral-feeding butterflyfishes: territoriality, foraging behavior, and prey defense. B.A. Biology, Phi Beta Kappa, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York. May 1988. RESEARCH EXPERIENCE: Senior Scientist, National Center for Natural Products Research, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. July 2006-present. Diseases of coral reef organisms. Chemical ecology of marine invertebrates. Phenotypic plasticity in chemical defenses of corals and sponges, particularly as they relate to pathogens and predators. Use of chemical ecology to direct drug discovery efforts from marine resources of Caribbean and Indo-Pacific reefs. Visiting Scientist, Caribbean Coral Reef Ecosystem Program, Smithsonian Marine Science Network. 2008-present. Prevalence and virulence of sponge diseases in the Caribbean. Visiting Scientist, Caribbean Marine Research Center, Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas. 2000-present. Chemical ecology, physiology and microbiology of corals and sponges as related to disease and other environmental stressors. Behavioral ecology of sponge- and coral-feeding fishes. Pheromones as signals for sex change in a marine goby. Antimicrobial and antipredator natural products from cave and reef sponges. Research Scientist, National Center for Natural Products Research and Ocean Biotechnology Center and Repository of the National Institute of Undersea Science and Technology, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. Sept. 2001-June 2006. Chemical ecology of marine invertebrates. Phenotypic plasticity in chemical defenses of corals, particularly as they relate to coral pathogens and predators. -

Partnership Fact Sheet

PARTNERSHIP FACT SHEET PORTMORE, JAMAICA + TOWNSVILLE, AUSTRALIA LOCATED IN THE ATLANTIC HURRICANE BELT, Portmore, Jamaica is extremely susceptible to hurricanes that RESULTS can cause severe flooding and widespread infrastructure damage. Portmore is a low-lying area on the southern coast of Jamaica. 1 Originally a predominantly agricultural area, the city transformed into a large residential community in the 1950s and became home Based off of a collective social learning for thousands of residents who worked in Kingston. Since then, workshop model from Townsville, the the population of Portmore has grown extremely rapidly, leading partnership hosted a workshop for 46 key it to become the largest residential area in the Caribbean. stakeholders from local government, civil society, and the national government in One of the greatest climate related risks to Portmore is the Portmore to prioritize climate actions that will potential impacts from tropical storms, storm surges and sea feed into Portmore’s Climate Action Plan. level rise. The coastal location of the city also renders it highly susceptible to incremental changes in sea levels and the potential 2 for inundation that will only worsen with future seal level rise. Portmore adopted climate education initiatives from Townsville that will work with students Recognizing that the city’s flood risk is increasing with the threat from elementary to high school on the of climate change, Portmore applied to be part of the CityLinks creation of sensors to monitor indoor energy partnership in the hopes of receiving technical assistance to better consumption and indoor temperatures. plan for future climate impacts. 3 After seeing the impacts white roofs had PARTNERING ON SHARED CLIMATE CHALLENGES in Townsville, Portmore is considering the Although, the distance between Townsville and Portmore design of municipal pilot projects that would couldn’t be greater, local government structure and shared encourage white roofs. -

"Free Negroes" - the Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 12-16-2015 "Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670 Patrick John Nichols Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Nichols, Patrick John, ""Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/100 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FREE NEGROES” – THE DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY ENGLISH JAMAICA AND THE BIRTH OF JAMAICAN MAROON CONSCIOUSNESS, 1655-1670 by PATRICK JOHN NICHOLS Under the Direction of Harcourt Fuller, PhD ABSTRACT The English conquest of Jamaica in 1655 was a turning point in the history of Atlantic World colonialism. Conquest displaced the Spanish colony and its subjects, some of who fled into the mountainous interior of Jamaica and assumed lives in isolation. This project reconstructs the historical experiences of the “negro” populations of Spanish and English Jamaica, which included its “free black”, “mulattoes”, indigenous peoples, and others, and examines how English cosmopolitanism and distinct interactions laid the groundwork for and informed the syncretic identities and communities that emerged decades later. Upon the framework of English conquest within the West Indies, I explore the experiences of one such settlement alongside the early English colony of Jamaica to understand how a formal relationship materialized between the entities and how its course inflected the distinct socio-political identity and emergent political agency embodied by the Jamaican Maroons. -

WHAT IS a FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, and PRODUCING LANDSCAPES in ST ELIZABETH, JAMAICA by Gary R. Schnakenberg a DISSERTATION

WHAT IS A FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, AND PRODUCING LANDSCAPES IN ST ELIZABETH, JAMAICA By Gary R. Schnakenberg A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Geography – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT WHAT IS A FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, AND PRODUCING LANDSCAPES IN ST. ELIZABETH, JAMAICA By Gary R. Schnakenberg This dissertation research examined the operation of discourses associated with contemporary globalization in producing the agricultural landscape of an area of rural Jamaica. Subject to European colonial domination from the time of Columbus until the 1960s and then as a small island state in an unevenly globalizing world, Jamaica has long been subject to operations of unequal power relationships. Its history as a sugar colony based upon chattel slavery shaped aspects of the society that emerged, and left imprints on the ethnic makeup of the population, orientation of its economy, and beliefs, values, and attitudes of Jamaican people. Many of these are smallholder agriculturalists, a livelihood strategy common in former colonial places. Often ideas, notions, and practices about how farms and farming ‘ought-to-be’ in such places results from the operations and workings of discourse. As advanced by Foucault, ‘discourse’ refers to meanings and knowledge circulated among people and results in practices that in turn produce and re-produce those meanings and knowledge. Discourses define what is right, correct, can be known, and produce ‘the world as it is.’ They also have material effects, in that what it means ‘to farm’ results in a landscape that emerges from those meanings. In Jamaica, meanings of ‘farms’ and ‘farming’ have been shaped by discursive elements of contemporary globalization such as modernity, competition, and individualism. -

The Muslim Maroons and the Bucra Massa in Jamaica

AS-SALAAMU-ALAIKUM: THE MUSLIM MAROONS AND THE BUCRA MASSA IN JAMAICA ©Sultana Afroz Introduction As eight centuries of glorious Muslim rule folded in Andalusia Spain in 1492, Islam unfolded itself in the West Indian islands with the Andalusian Muslim mariners who piloted Columbus discovery entourage through the rough waters of the Atlantic into the Caribbean. Schooled in Atlantic navigation to discover and to dominate the sea routes for centuries, the mission for the Muslim mariners was to find the eternal peace of Islam as they left al-Andalus/Muslim Spain in a state of ‘empty husks’ and a land synonym for intellectual and moral desolation in the hands of Christendom Spain. The Islamic faith made its advent into Jamaica in1494 as these Muslim mariners on their second voyage with Columbus set their feet on the peaceful West Indian island adorned with wooded mountains, waterfalls, sandy beaches and blue seas. The seed of Islam sown by the Mu’minun (the Believers of the Islamic faith) from al-Andalus gradually propagated through the enslaved African Muslims from West Africa brought to serve the plantation system in Jamaica. Their struggle or resistance (jihad) against the slave system often in the form of flight or run away (hijra) from the plantations led many of them to form their own community (ummah), known as Maroon communities, a feature then common in the New World plantation economy.1 Isolationism and lack of Islamic learning made Islam oblivion in the Maroon societies, while the enslaved African Muslims on the plantations saw their faith being eclipsed and subdued by the slave institution, the metropolitan powers and the various Christian churches with their draconian laws.