Budde, Rebecca Qualification of Children's Rights Experts Phd 28.9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Legal Discourse on Child Trafficking: the Re/Production of Inequalities and Persistence of Child Criminalization

The London School of Economics and Political Science American Legal Discourse on Child Trafficking: The Re/production of Inequalities and Persistence of Child Criminalization Pantea Javidan A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, January 2017 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,751 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help: I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Reza Javidan, PhD, Sociology (1995). 2 Abstract The criminalization of children commercially-sexually exploited through prostitution persists despite trafficking laws recognizing this as one of the worst forms of exploitation committed against the most vulnerable social group. This thesis examines the re/production of inequalities in American legal discourse on child trafficking, and why child criminalization persists in this context. -

Infant Nation: Childhood Innocence and the Politics of Race in Contemporary American Fiction De

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Infant Nation: Childhood Innocence and the Politics of Race in Contemporary American Fiction Debra T. Werrlein, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertation directed by: Professor Linda Kauffman Department of English In fant Nation considers literary representations of childhood as sites where anxieties about race, class and gender inequalities converge. Popular and canonical representations of American childhood often revere it as a condition that precedes history, lack s knowledge, and thus, avoids accountability. I argue that invocations of this depoliticized ideal mask systems of privilege, particularly relating to white middle - class masculinity. My study highlights literature published between 1970 and 1999, a perio d marked by growing concern regarding boundaries of race and nation. With special attention to postcolonial and critical race theories, I argue that the authors here portray the United States as a nation infantilized by its desire to reclaim a mythically innocent past. In untidy formulations of nation that mirror their disjointed narrative styles, the novels interfere with the operation of nostalgia in American memory. They revise the ideal of innocent childhood to model a form of citizenship deeply engaged in acts of historical recuperation. I respond to theories of postmodern literature and cultural studies that emphasize the central role memory plays in shaping our future, presenting an analysis I feel is especially urgent at a time when neo -conservat ive policy -makers subscribe to a Trent Lott -style nostalgia for a mythically innocent pre - Civil Rights era. Chapter One examines Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters (1990). I argue that Hagedorn cedes authentic history to the corrosive powers of assimilationis m and consumerism, invoking multiple stories of history’s loss instead. -

Pre-Verbal Trauma, Dissociation and the Healing Process Dorothy Dreier Scotten Lesley University

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Educational Studies Dissertations Graduate School of Education (GSOE) 2003 Pre-Verbal Trauma, Dissociation and the Healing Process Dorothy Dreier Scotten Lesley University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations Part of the Education Commons, Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Commons, and the Trauma Commons Recommended Citation Scotten, Dorothy Dreier, "Pre-Verbal Trauma, Dissociation and the Healing Process" (2003). Educational Studies Dissertations. 87. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations/87 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Education (GSOE) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lesley University, Sherrill Library http://www.archive.org/details/preverbaltraumadOOdoro LUDCKE LIBRARY Lesley University 30 Mellen Street Cambridge. IWA 02138-2790 FOR REFERENCE Do Not Take From This Room PRE-VERBAL TRAUMA, DISSOCIATION AND THE HEALING PROCESS A DISSERTATION submitted by DOROTHY DREIER SCOTTEN In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lesley University November 1,2002 fn lovlmg memory of Smnt Ajath Singh, I aedlemte tbis Journey of disoovery , AKNOWLEDGEMENTS How truly blessed I feel with the loving presence of all my family, friends, colleagues, and participants who have supported this work from beginning to end. I formally acknowledge: my beloved mentor, Dr. Lisa Wolfe, whose gracious support love, and patience sustained me; Dr. Vivien Marcow-Speiser, my former committee chair who gave this research life; Dr. -

The Adultification of Immigrant Children

ARTICLES THE ADULTIFICATION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN LAILA HLASS* There is evidence . that the child receives the worst of both worlds [in juvenile court]: that he gets neither the protections accorded to adults nor the solicitous care and regenerative treatment postulated for children. ÐJustice Fortas1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................... 200 I. CONSTRUCTIONS OF CHILDHOOD UNDER IMMIGRATION LAW . 205 A. Infantilization of Migrant Children . 207 B. Adulti®cation of Migrant Children . 209 C. Exceptionalism: Unaccompanied Minors . 217 II. EVISCERATION OF UNACCOMPANIED MINOR EXCEPTIONALISM . 222 A. Anti-Immigrant Child Public Discourse . 222 B. Weaponization of Immigration Agencies . 228 1. Apprehension and Detention System . 229 * Professor of Practice, Tulane University Law School. For helpful insights and conversations at var- ious stages of this project, thanks to Amna Akbar, Sabrineh Ardalan, Sameer Ashar, Jason Cade, Gabriel Chin, Rose Cuison Villazor, Adam Feibelman, Kate Evans, Eve Hanan, CeÂsar CuauhteÂmoc GarcõÂa HernaÂndez, Lindsay M. Harris, Hiroshi Motomura, Jayesh Rathod, Shalini Ray, Andrew I. Schoenholtz, Philip G. Schrag, Bijal Shah, Sarah Sherman-Stokes, and Mae Quinn. This paper bene®ted from presenta- tions at the Immigration Law Scholars Conference, the American Constitution Society Junior Scholars Public Law Workshop, the LatCrit Biennial Conference, NYU Clinical Law Review Writers' Workshop, and the UCLA Emerging Immigration Scholars Conference. © 2020, Laila Hlass. 1. Kent v. U.S., 383 U.S. 541, 556 (1966). 199 200 GEORGETOWN IMMIGRATION LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 34:199 2. Removal and Adjudication System . 239 III. EVOLUTION AND DERIVED PRINCIPLES FROM JUVENILE JUSTICE . 246 A. More Rights, Not Fewer ......................... 247 B. The Super-Predator Myth ........................ 251 C. Towards a More Inclusive Childhood . -

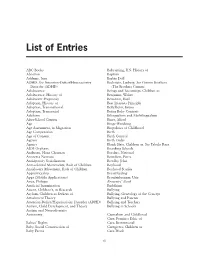

List of Entries & Readers Guide

List of Entries ABC Books Babysitting, U.S. History of Abortion Baptism Addams, Jane Barbie Doll ADHD. See Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Bechstein, Ludwig. See Grimm Brothers Disorder (ADHD) (The Brothers Grimm) Adolescence Beings and Becomings, Children as Adolescence, History of Benjamin, Walter Adolescent Pregnancy Bernstein, Basil Adoption, History of Best Interests Principle Adoption, Transnational Bettelheim, Bruno Adoption, Transracial Better Baby Contests Adultism Bilingualism and Multilingualism After-School Centers Binet, Alfred Age Binge-Watching Age Assessment, in Migration Biopolitics of Childhood Age Compression Birth Age of Consent Birth Control Ageism Birth Order Agency Blank Slate, Children as. See Tabula Rasa AIDS Orphans Boarding Schools Andersen, Hans Christian Borders, National Anorexia Nervosa Bourdieu, Pierre Anticipatory Socialization Bowlby, John Anti-colonial Movements, Role of Children Boyhood Antislavery Movement, Role of Children Boyhood Studies Apprenticeship Breastfeeding Apps (Mobile Applications) Bronfenbrenner, Urie Ariès, Philippe Brownies’ Book Artificial Insemination Buddhism Assent, Children’s, in Research Bullying Asylum, Children as Seekers of Bullying, Genealogy of the Concept Attachment Theory Bullying and Parents Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Bullying and Teachers Autism, Child Development, and Theory Bullying in Schools Autism and Neurodiversity Autonomy Capitalism and Childhood Care, Feminist Ethic of Babies’ Rights Care, Institutional Baby, Social Construction of Caregivers, -

Piaget, Disney Eo Eduentretenimento

ISSN: 1984-1655 PIAGET, DISNEY E O EDUENTRETENIMENTO: POR UMA PSICOLOGIA TRANSPESSOAL DAS ORGANIZAÇÕES Tristan Guillermo Torriani1 Resumo A Psicologia Transpessoal das Organizações preocupa-se com o desenvolvi- mento de indivíduos que podem crescer em equilíbrio físico, emocional, intelec- tual e espiritual ao longo de sua vida. Ela compartilha muitas posições de Pi- aget sobre equilíbrio dinâmico, sobre adaptação através da assimilação e aco- modação, sobre autonomia e sobre a necessidade de respeitar o estágio de de- senvolvimento da criança. Também compartilha o interesse de Disney pela lite- ratura infantil e folclore como um caminho para a autodescoberta. Usando teses propostas por R. Steiner, M. P. Hall e os teóricos do Eneagrama, a teoria piage- tiana e as suas distinções técnicas são assimiladas para analisar o fenômeno da influência global da Disney. É dada especial atenção às questões do adultocen- trismo, do etnocentrismo e da apropriação, substituição e banalização comercial multiculturalista das tradições ancestrais. Apesar das melhores intenções de Walt, o eduentretenimento se mostra como uma espada de dois gumes com po- tencial para fazer mais mal do que bem se os cidadãos forem marginalizados a ponto de não serem mais livres para criticar, boicotar ou de resistir ao conteúdo que lhes for imposto pelos grandes conglomerados midiáticos. Palavras Chave: Walt Disney; Jean Piaget; Rudolf Steiner; Organização; Taois- mo. 1 Assistant Professor, State University of Campinas (Universidade Estadual de Campinas - UNICAMP), School of Applied Sciences (Faculdade de Ciências Aplicadas - FCA), Limeira Campus. Email: tris- [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6186-3836 41 Volume 13 Número 1 – Jan-Jul/2021 www.marilia.unesp.br/scheme ISSN: 1984-1655 PIAGET, DISNEY AND EDUTAINMENT: TOWARDS A TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOLOGY OF ORGANIZATIONS Abstract Transpersonal Psychology of Organizations is concerned with the development of individuals who can grow in physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual balance throughout their lifespans. -

Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21St Century

Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century By Samuel Bañales A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Charles L. Briggs, chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Fall 2012 Copyright © by Samuel Bañales 2012 ABSTRACT Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century by Samuel Bañales Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California at Berkeley Professor Charles L. Briggs, chair By focusing on the politics of age and (de)colonization, this dissertation underscores how the oppression of young people of color is systemic and central to society. Drawing upon decolonial thought, including U.S. Third World women of color, modernity/coloniality, decolonial feminisms, and decolonizing anthropology scholarship, this dissertation is grounded in the activism of youth of color in California at the turn of the 21st century across race, class, gender, sexuality, and age politics. I base my research on two interrelated, sequential youth movements that I argue were decolonizing: the various walkouts organized by Chican@ youth during the 1990s and the subsequent multi-ethnic "No on 21" movement (also known as the "youth movement") in 2000. Through an interdisciplinary activist ethnography, which includes speaking to and conducting interviews with many participants and organizers of these movements, participating in local youth activism in various capacities, and evaluating hundreds of articles—from mainstream media to "alternative" sources, like activist blogs, leftist presses, and high school newspapers—I contend that the youth of color activism that is examined here worked towards ontological, epistemological, and institutional decolonization. -

The Adultification of Black Girls

Center on Race, Law & Justice Diversity and Inclusion Speaker Series From the Classroom to the Courtroom: The Adultification of Black Girls Thalia González Senior Visiting Scholar, Center on Poverty and Inequality, Georgetown University Law Center CLE MATERIALS Tuesday, March 13, 2018 4 – 5:30 p.m., Program Fordham Law School Hill Faculty Conference Room (7-119) 150 W 62nd St New York, NY 10023 Table of Contents CLE Materials Blind Discretion Girls of Color & Delinquency Girlhood Interrupted Realizing Restorative Justice: Legal Rules and Standards for School Discipline Reform Restorative Practices: Righting the Wrongs of Exclusionary School Discipline The School to Prison Pipeline’s Legal Architecture: Lessons From the Spring Valley Incident and its Aftermath Lenhardt, Robin 3/5/2018 For Educational Use Only BLIND DISCRETION: GIRLS OF COLOR & DELINQUENCY..., 59 UCLA L. Rev. 1502 59 UCLA L. Rev. 1502 UCLA Law Review August, 2012 Symposium Overpoliced and Underprotected: Women, Race, and Criminalization II. Crime, Punishment, and the Management of Racial Marginality Jyoti Nanda Copyright (c) 2012 Regents of the University of California; Jyoti Nanda BLIND DISCRETION: GIRLS OF COLOR & DELINQUENCY IN THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM Abstract The juvenile justice system was designed to empower its decisionmakers with a wide grant of discretion in hopes of better addressing youth in a more individualistic and holistic, and therefore more effective, manner. Unfortunately for girls of color in the system, this discretionary charter given to police, probation officers, and especially judges has operated without sufficiently acknowledging and addressing their unique position. Indeed, the dearth of adequate gender/ race intersectional analysis in the research and the stark absence of significant system tools directed at the specific characteristics of and circumstances faced by girls of color have tracked alarming trends such as the rising number of girls in the system and the relatively harsher punishment they receive compared to boys for similar offenses. -

Youth Volunteering in Australia: an Evidence Review Associate Professor Lucas Walsh and Dr Rosalyn Black

Youth volunteering in Australia: An evidence review Associate Professor Lucas Walsh and Dr Rosalyn Black A What Works for Kids Evidence Review Youth volunteering in Australia: An evidence review. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth © ARACY 2015 The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) owns copyright of all material in this report. You may reproduce this material in unaltered form only (acknowledging the source) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Commercial use of material in this report is prohibited. Except as permitted above you must not copy, adapt, publish, distribute or commercialise any material contained in this publication without ARACY’s permission. ISBN: 978-1-76028-313-1 Disclaimer This report has been prepared for the National Youth Affairs Research Scheme (NYARS) and is intended to provide background research and other information as a basis for discussion. The views expressed in the report are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government, State and Territory Governments or the Education Council. NYARS was established in 1985 as a cooperative funding arrangement between federal, state and territory governments to facilitate nationally based research into current social, political and economic factors affecting young people. NYARS operates under the auspices of the Education Council (formerly Standing Council on School Education and Early Childhood). Suggested citation Walsh, L., & Black, R. (2015). Youth volunteering -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Once Upon a Sibyl's Tongue: Conjuring Fairy Tale [Hi]stories for Power and Pleasure Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1bq4g956 Author Luce, Christina Elizabeth Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ONCE UPON A SIBYL’S TONGUE: CONJURING FAIRY TALE [HI]STORIES FOR POWER AND PLEASURE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in LITERATURE by Christina Luce June 2013 The Thesis of Christina Luce is approved: _______________________________ Professor Wlad Godzich, Chair _______________________________ Professor Loisa Nygaard _______________________________ Professor Murray Baumgarten _______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Christina E. Luce 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Zipes: To Subvert or Not to Subvert 15 III. Warner: Metamorphic Matters 56 IV. Relativity and Humanism Beyond the Academy: Reading Warner Against Zipes’ Grain 112 V. Conclusion 129 Bibliography 138 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Cinderella, Arthur Rackham, 1919. Sur La Lune Fairy Tales. <http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/illustrations/cinderella/ rackhamcindy2.html>. The Brothers Grimm: Lily Collins in Mirror Mirror and Kristen Stewart in Snow White and the Huntsman, Relativity Media and Universal Pictures, 2012. The Examiner. <http://www.examiner.com/article/lily-collins-speaks-up-on- kristen-stewart-s-snow-white-and-the-huntsman>. Cinderella, George Cruikshank, 1854. San Diego State University Blogspot. <http://sdsuchildlit.blogspot.com/2013/04/cinderella-in-pictures-through- ages.html>. Barbe-Bleue, Gustave Doré, 1862. -

Understanding Ageing in Contemporary Poland: Social And

Understanding Ageing in Contemporary Poland: Social and Cultural Perspectives Online access: http://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/publication/54526 Understanding Ageing in Contemporary Poland: Social and Cultural Perspectives eds Stella Grotowska, Iwona Taranowicz Wrocław 2014 Projekt współfinansowany z budżetu Województwa Dolnośląskiego The project was co-financed from the funds of the Self-Government of Lower Silesia Peer review: prof. dr hab. Maria Libiszowska-Żółtkowska © Copyright by Authors Cover design: Patryk Bochenek Typesetting: Marta Uruska, Tomasz Kalota - eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-63322-24-3 Publishing House Instytut Socjologii Uniwersytet Wrocławski ul. Koszarowa 3 bud. 20 51-149 Wrocław tel. +48 71 375 50 97 www.socjologia.uni.wroc.pl CONTENTS Introduction ..............................................................................................................9 WHAT IS OLD AGE NO W ADAYS AND HO W DO W E SPEAK ABOUT IT ? ............................11 Iwona Taranowicz Deconstructing old age? On the evolution of social concepts of the late stage of life ........................................................................................................................13 Stella Grotowska Old age – roleless role or time of freedom ..............................................................25 Anna Gomóła Problems with starość (age). On natural and scientific categories ..........................37 Iwona Burkacka Are there any attractive names for elderly people in Polish? ..................................47 PRIVA C Y -

Beyond the Tower: Concepts and Models for Service-Learning in Philosophy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 449 737 HE 033 737 AUTHOR Lisman, C. David, Ed.; Harvey, Irene E., Ed. TITLE Beyond the Tower: Concepts and Models for Service-Learning in Philosophy. AAHE's Series on Service-Learning in the Disciplines. INSTITUTION American Association for Higher Education, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-1-56377-016-4 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 231p.; For other documents in this series, see HE 033 726-743. Initial funding for this series was supplied by Campus Compact. AVAILABLE FROM American Association for Higher Education, One Dupont Circle, Suite 360, Washington, DC 20036-1110 ($28.50). Tel: 202-293-6440; Fax: 202-293-0073; E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: www.aahe.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Art; College Students; Community Services; Critical Thinking; Democracy; Ethics; Feminism; Higher Education; Intellectual Disciplines; *Philosophy; Postmodernism; Poverty; School Community Programs; *Service Learning; Social Cognition; Student Participation; Student Volunteers; Teaching Methods; Theory Practice Relationship; Thinking Skills IDENTIFIERS Dewey (John); Horton (Myles); Pragmatism; Praxis; Socrates ABSTRACT This volume is part of a series of 18 monographs service learning and the academic disciplines. This collection focuses on the use of service learning as an approach to teaching and learning in philosophy. After a Foreword by David A. Hoekema and an Introduction by C. David Lisman, chapters in Part 1,"Service-Learning as a Mode of Philosophical Inquiry," focus on the epistemological and philosophical aspects of service-learning as a pedagogy; titles include: "Knowledge, Foundations, and Discourse: Philosophical Support for Service-Learning" (Goodwin Liu); "Feminism, Postmodernism, and Service-Learning" (Irene E.