Piaget, Disney Eo Eduentretenimento

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budde, Rebecca Qualification of Children's Rights Experts Phd 28.9

__________________________________________________ Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie der Freien Universität Berlin Department of Education and Psychology _______________________________________________________ “Qualification of Children’s Rights Experts in Academia- a Qualitative Impact Assessment“ Dissertation to attain the Academic Degree of Dr. phil Presented by Diplom-Kulturwissenschaftlerin Rebecca Budde Date of defence: 26th April 2018 __________________________________________________ First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Uwe Gellert Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Manfred Liebel ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Gemeinsame Promotionsordnung zum Dr. phil. / Ph.D. der Freien Universität Berlin vom 2. Dezember 2008 (FU-Mitteilungen 60/2008) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my mentor, Prof. Dr. Manfred Liebel, with whom I have been working in the framework of the European Network of Masters in Children’s Rights and subsequently in the M.A. Childhood Studies and Chil- dren’s Rights over the past ten years. He has been a major source of inspiration, with his seemingly endless ideas and thoughts about how children can come by their rights and how we, as researchers, can contribute to this. The members of the European Network of Masters in Children’s Rights/ Chil- dren’s Rights European Academic Network have an incredibly important role, without us having come together this dissertation would have never been written- thank you. Of course, I thank the graduates and students of the MACR who have given me their time to answer the many questions I have asked about their experience in the programme, the data base on which this study is based. I would also like to thank my colleagues, Dr. Urszula Markowska-Manista, with her rich experience as researcher and publisher in the field of children’s rights. -

The Situation of Violence of Girls and Adolescents in Guatemala”

Alternative Report on the Convention on the Rights of the Child “THE SITUATION OF VIOLENCE OF GIRLS AND ADOLESCENTS IN GUATEMALA” 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Asociación Red de Jóvenes para la Incidencia Política –INCIDEJOVEN- (The Youth Network for Political Advocacy), as a member of Red Latinoamericana y Caribeña de Jóvenes por los Derechos Sexuales (The Latin American and Caribbean Youth Network for Sexual Rights)–RedLAC-, in association with Asociación Guatemalteca de Humanistas Seculares, ONG (The Guatemalan Association of Secular Humanists), who work for the promotion and defense of sexual and reproductive rights of adolescents and young people and for the respect of the secularity of the State in Guatemala, present the following report in the framework of the 77th period of meetings of the Committee on the Rights of the Child in order to demonstrate the conditions of violence in which the girls and adolescent women of Guatemala live in. This report seeks to analyse the various manifestations of this violence, and the lack of an efficient response by the State to address structural problems, which have led to tragedies, such as the events of the children's home; Hogar Virgen de la Asunción. Moreover, it will emphasize the existing link between the violence and forced pregnancies and forced maternities and the lack of access to Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE). 2. Girls and adolescent women in Guatemala are constantly facing violence, in its various manifestations: physical, sexual, psychological, economic, structural and symbolic violence -

National Analysis on Violence Against LGBTI+ Children

National analysis on violence against LGBTI+ children SPAIN Authors Jose Antonio Langarita (coord.), Núria Sadurní, and Pilar Albertín (Universitat de Girona) Joan Pujol, Marisela Montenegro, and Beatriz San Román (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Project information Project Title: Diversity and childhood. Changing social attitudes towards gender diversity in children across Europe Project number: 856680 Involved countries: Belgium, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain December 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. This project was funded by European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (2014-2020). The content of this website represents the views of the authors only and is their sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains. Contents Introduction: Research Design and Sample…………………………………………………………………………4 1. Legal and political context regarding LGBTI+ rights…………………………………………………………7 1.1. Timeline of LGBTI+ rights in Spain .......................................................................................... 10 1.2. Relevant statistical data about the LGBTI+ situation in your country .................................... 11 2. DaC Areas of Intervention: schools, health, family, public spaces and media………………..13 2. 1. Education .............................................................................................................................. -

Any Honest Conversation About Youth Must Address the Challenges That

Any honest conversation about youth must address the challenges that young people and adult allies face when they work to engage children and youth throughout our communities. By their very existence, youth programs are made to respond to these challenges; ignoring them is not being honest about the purpose of youth programs. Racism, sexism, classism, homophobia… the list of challenges facing young people is enormous. However, one of the core challenges is a common experience that all people face early in their lives. That challenge is discrimination against children and youth. Discrimination occurs anytime one thing is chosen before something else. That is often a good thing – otherwise, why wouldn’t we all steal our food instead of growing it or buying it? We all discriminate everyday. However, discrimination often excludes people because of false bias or prejudice. Discrimination against children and youth is caused by the bias adults have for other adults that causes them to discriminate against young people. Bias for adults is called adultism. When something is based on adultism, it is called adultcentrism.While adultism is sometimes appropriate, adultcentrism is often inappropriate. Compulsory education can force students to disengage from the love of learning. Youth development programs can force youth to disconnect from adults. Almost every activity that is for young people is decided upon, developed, assessed and redeveloped without young people. That is adultcentrism. Language, programs, teaching styles, and all relationships between young people and adults are adultcentric. The most “youth-friendly” adults are often adultist, assuming that youth need them – which, while it may be true, is still centered on adult perspectives. -

American Legal Discourse on Child Trafficking: the Re/Production of Inequalities and Persistence of Child Criminalization

The London School of Economics and Political Science American Legal Discourse on Child Trafficking: The Re/production of Inequalities and Persistence of Child Criminalization Pantea Javidan A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, January 2017 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,751 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help: I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Reza Javidan, PhD, Sociology (1995). 2 Abstract The criminalization of children commercially-sexually exploited through prostitution persists despite trafficking laws recognizing this as one of the worst forms of exploitation committed against the most vulnerable social group. This thesis examines the re/production of inequalities in American legal discourse on child trafficking, and why child criminalization persists in this context. -

Summit Poster Notes.Docx

SUMMIT POSTER NOTES ROLES Facilitator Manage process and time Participants Participate Fully Tabletop Dialogue Recorder Time Keeper Reporter Norms Take good care of yourself Reduce distractions Listen well (inner wisdom and others) Seek to understand Manage your “airtime” Manage your volume Come together efficiently Others? Expect and acknowledge personal discomfort Watch assumptions Participate and have fun Additional Norms Speak your own truth Honor confidentiality of personal stories Pause and make room for silence Respect and acknowledge others Agree to disagree DISTRIBUTION OF OSD RESOURCES ● School districting/neighborhoods ● Busing ● PTA ● School size o Efficiency, growth, capacity small programs ● Partnership o Contact Food Services! ● Focus on “our kids” community wide ● Data-driven not and number driven LGBTQ + ● Rights and Resources ● Queer staff required for a diverse staff ● Need gay sex education and safety and health education for trans youth ● Fictionalization and fetishization of LGBTQ+ ● Training for teachers on pronouns ● Teaching queer history ● Discipline students using derogatory names ● Legality of discrimination by educators? ● Identification of sexual and gender identities ● Mental health benefits of gender neutral bathrooms ● Locker rooms and the uncomfortability of changing in front of other students ● Harassment of “dead naming” students ● How to defend students being harassed ● Romanticizing straight children ● Demonization of queer youth Summit Notes from Katrina Telnack, Reeves Middle School Mental Health in Schools ● ALL students meet with counselor once a week, or every set amount of time( preferably 2 weeks, if necessary, a month) Make sure it is ALL students, to reduce the stigma around ‘going to the counselor’, and so they can check in and talk to someone. -

Infant Nation: Childhood Innocence and the Politics of Race in Contemporary American Fiction De

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Infant Nation: Childhood Innocence and the Politics of Race in Contemporary American Fiction Debra T. Werrlein, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertation directed by: Professor Linda Kauffman Department of English In fant Nation considers literary representations of childhood as sites where anxieties about race, class and gender inequalities converge. Popular and canonical representations of American childhood often revere it as a condition that precedes history, lack s knowledge, and thus, avoids accountability. I argue that invocations of this depoliticized ideal mask systems of privilege, particularly relating to white middle - class masculinity. My study highlights literature published between 1970 and 1999, a perio d marked by growing concern regarding boundaries of race and nation. With special attention to postcolonial and critical race theories, I argue that the authors here portray the United States as a nation infantilized by its desire to reclaim a mythically innocent past. In untidy formulations of nation that mirror their disjointed narrative styles, the novels interfere with the operation of nostalgia in American memory. They revise the ideal of innocent childhood to model a form of citizenship deeply engaged in acts of historical recuperation. I respond to theories of postmodern literature and cultural studies that emphasize the central role memory plays in shaping our future, presenting an analysis I feel is especially urgent at a time when neo -conservat ive policy -makers subscribe to a Trent Lott -style nostalgia for a mythically innocent pre - Civil Rights era. Chapter One examines Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters (1990). I argue that Hagedorn cedes authentic history to the corrosive powers of assimilationis m and consumerism, invoking multiple stories of history’s loss instead. -

Pre-Verbal Trauma, Dissociation and the Healing Process Dorothy Dreier Scotten Lesley University

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Educational Studies Dissertations Graduate School of Education (GSOE) 2003 Pre-Verbal Trauma, Dissociation and the Healing Process Dorothy Dreier Scotten Lesley University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations Part of the Education Commons, Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Commons, and the Trauma Commons Recommended Citation Scotten, Dorothy Dreier, "Pre-Verbal Trauma, Dissociation and the Healing Process" (2003). Educational Studies Dissertations. 87. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations/87 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Education (GSOE) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lesley University, Sherrill Library http://www.archive.org/details/preverbaltraumadOOdoro LUDCKE LIBRARY Lesley University 30 Mellen Street Cambridge. IWA 02138-2790 FOR REFERENCE Do Not Take From This Room PRE-VERBAL TRAUMA, DISSOCIATION AND THE HEALING PROCESS A DISSERTATION submitted by DOROTHY DREIER SCOTTEN In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lesley University November 1,2002 fn lovlmg memory of Smnt Ajath Singh, I aedlemte tbis Journey of disoovery , AKNOWLEDGEMENTS How truly blessed I feel with the loving presence of all my family, friends, colleagues, and participants who have supported this work from beginning to end. I formally acknowledge: my beloved mentor, Dr. Lisa Wolfe, whose gracious support love, and patience sustained me; Dr. Vivien Marcow-Speiser, my former committee chair who gave this research life; Dr. -

The Adultification of Immigrant Children

ARTICLES THE ADULTIFICATION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN LAILA HLASS* There is evidence . that the child receives the worst of both worlds [in juvenile court]: that he gets neither the protections accorded to adults nor the solicitous care and regenerative treatment postulated for children. ÐJustice Fortas1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................... 200 I. CONSTRUCTIONS OF CHILDHOOD UNDER IMMIGRATION LAW . 205 A. Infantilization of Migrant Children . 207 B. Adulti®cation of Migrant Children . 209 C. Exceptionalism: Unaccompanied Minors . 217 II. EVISCERATION OF UNACCOMPANIED MINOR EXCEPTIONALISM . 222 A. Anti-Immigrant Child Public Discourse . 222 B. Weaponization of Immigration Agencies . 228 1. Apprehension and Detention System . 229 * Professor of Practice, Tulane University Law School. For helpful insights and conversations at var- ious stages of this project, thanks to Amna Akbar, Sabrineh Ardalan, Sameer Ashar, Jason Cade, Gabriel Chin, Rose Cuison Villazor, Adam Feibelman, Kate Evans, Eve Hanan, CeÂsar CuauhteÂmoc GarcõÂa HernaÂndez, Lindsay M. Harris, Hiroshi Motomura, Jayesh Rathod, Shalini Ray, Andrew I. Schoenholtz, Philip G. Schrag, Bijal Shah, Sarah Sherman-Stokes, and Mae Quinn. This paper bene®ted from presenta- tions at the Immigration Law Scholars Conference, the American Constitution Society Junior Scholars Public Law Workshop, the LatCrit Biennial Conference, NYU Clinical Law Review Writers' Workshop, and the UCLA Emerging Immigration Scholars Conference. © 2020, Laila Hlass. 1. Kent v. U.S., 383 U.S. 541, 556 (1966). 199 200 GEORGETOWN IMMIGRATION LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 34:199 2. Removal and Adjudication System . 239 III. EVOLUTION AND DERIVED PRINCIPLES FROM JUVENILE JUSTICE . 246 A. More Rights, Not Fewer ......................... 247 B. The Super-Predator Myth ........................ 251 C. Towards a More Inclusive Childhood . -

Homeplaces and Spaces: Black and Brown Feminists and Girlhood Geographies of Agency

HOMEPLACES AND SPACES: BLACK AND BROWN FEMINISTS AND GIRLHOOD GEOGRAPHIES OF AGENCY Elizabeth Gale Greenlee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Laura Halperin María DeGuzmán James W. Coleman Daniel Anderson Minrose Gwin Jennifer Ho © 2019 Elizabeth Gale Greenlee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Elizabeth Gale Greenlee: Homeplaces and Spaces: Black and Brown Feminists and Girlhood Geographies of Agency (Under the direction of Laura Halperin and María DeGuzmán) During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, noted Chicana feminists such Gloria Anzaldúa and Pat Mora, as well as Black feminists like Octavia Butler and bell hooks frequently turned to children’s literature or youth-centric literature as a means to confront social injustice in American society. My dissertation considers this literary investment in Black and Brown girlhoods by examining feminist-authored children’s picture books, middle-grade and youth- centric literary novels featuring girl protagonists. Specifically, I examine how Black, Chicana and Mexican American feminist writers consistently render girlhood in relation to geography. Not limiting my investigation to geopolitical bodies, I pay particular attention to everyday spatial terrains such as the girls’ homes, schools, community centers, and playgrounds. These seemingly ordinary spaces of girlhood merge public and private and constitute key sites for nation building. They also provide fertile ground for the development of Black and Brown girl spatial citizenship: girl-centered, critical vantage points from which readers may view operations of power and privilege. -

Conceptualization and Measurement of Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: a Two-Study Mixed Methods Investigation

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses October 2018 Conceptualization and Measurement of Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: A Two-Study Mixed Methods Investigation Shereen El Mallah University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Community Psychology Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, Developmental Psychology Commons, Education Commons, Multicultural Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation El Mallah, Shereen, "Conceptualization and Measurement of Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: A Two-Study Mixed Methods Investigation" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1336. https://doi.org/10.7275/12766147 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1336 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONCEPTUALIZATION AND MEASUREMENT OF ADOLESCENT PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR: A TWO-STUDY MIXED METHODS INVESTIGATION A Dissertation Presented by SHEREEN EL MALLAH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2018 Developmental Psychology © Copyright by Shereen El Mallah 2018 All -

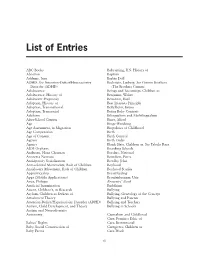

List of Entries & Readers Guide

List of Entries ABC Books Babysitting, U.S. History of Abortion Baptism Addams, Jane Barbie Doll ADHD. See Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Bechstein, Ludwig. See Grimm Brothers Disorder (ADHD) (The Brothers Grimm) Adolescence Beings and Becomings, Children as Adolescence, History of Benjamin, Walter Adolescent Pregnancy Bernstein, Basil Adoption, History of Best Interests Principle Adoption, Transnational Bettelheim, Bruno Adoption, Transracial Better Baby Contests Adultism Bilingualism and Multilingualism After-School Centers Binet, Alfred Age Binge-Watching Age Assessment, in Migration Biopolitics of Childhood Age Compression Birth Age of Consent Birth Control Ageism Birth Order Agency Blank Slate, Children as. See Tabula Rasa AIDS Orphans Boarding Schools Andersen, Hans Christian Borders, National Anorexia Nervosa Bourdieu, Pierre Anticipatory Socialization Bowlby, John Anti-colonial Movements, Role of Children Boyhood Antislavery Movement, Role of Children Boyhood Studies Apprenticeship Breastfeeding Apps (Mobile Applications) Bronfenbrenner, Urie Ariès, Philippe Brownies’ Book Artificial Insemination Buddhism Assent, Children’s, in Research Bullying Asylum, Children as Seekers of Bullying, Genealogy of the Concept Attachment Theory Bullying and Parents Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Bullying and Teachers Autism, Child Development, and Theory Bullying in Schools Autism and Neurodiversity Autonomy Capitalism and Childhood Care, Feminist Ethic of Babies’ Rights Care, Institutional Baby, Social Construction of Caregivers,