Superiors General 1952-1988 Brothers Josaphat 1952-1964 Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule and Foundational Documents

Rule and Foundational Documents Frontispiece: facsimile reproduction of a page—chapter 22, “Rules Concern- ing the Good Order and Management of the Institute”—from the Rule of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the 1718 manuscript preserved in the Rome archives of the Institute. Photo E. Rousset (Jean-Baptiste de La Salle; Icono- graphie, Boulogne: Limet, 1979, plate 52). Rule and Foundational Documents John Baptist de La Salle Translated and edited by Augustine Loes, FSC, and Ronald Isetti Lasallian Publications Christian Brothers Conference Landover, Maryland Lasallian Publications Sponsored by the Regional Conference of Christian Brothers of the United States and Toronto Editorial Board Luke Salm, FSC, Chairman Paul Grass, FSC, Executive Director Daniel Burke, FSC William Mann, FSC Miguel Campos, FSC Donald C. Mouton, FSC Ronald Isetti Joseph Schmidt, FSC Augustine Loes, FSC From the French manuscripts, Pratique du Règlement journalier, Règles communes des Frères des Écoles chrétiennes, Règle du Frère Directeur d’une Maison de l’Institut d’après les manuscrits de 1705, 1713, 1718, et l’édition princeps de 1726 (Cahiers lasalliens 25; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1966); Mémoire sur l’Habit (Cahiers lasalliens 11, 349–54; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1962); Règles que je me suis imposées (Cahiers lasalliens 10, 114–16; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1979). Rule and Foundational Documents is volume 7 of Lasallian Sources: The Complete Works of John Baptist de La Salle Copyright © 2002 by Christian Brothers Conference All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2002101169 ISBN 0-944808-25-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-944808-26-3 (paper) Cover: Portrait of M. -

Church Hears Completioh: Chapel Plahs Drawh Bishop Tief of Concordia, Kans., Resigns See

CHURCH HEARS COMPLETIOH: CHAPEL PLAHS DRAWH BISHOP TIEF OF CONCORDIA, KANS., RESIGNS SEE ............ ' ............................................ ....... I ■ i ' ' Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1938—Permission to Reproduce, Excepting on Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Isstue As Qallagher Memorial Chapel Will Appear $40,000 Sanctuary and SinKing Tower Will Honor Memory of Famous Reddy Gallagher, Sports Leader. DEN VER CATHOLIC ^ - ''' .Will Reside at St. REGISTER Priest Designs Edi Mary’s Hospital, The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We Have fice ; Memorial De Hartford, Conn. Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, and Seven Smaller Services. tails Listed GIVEN TITULAR VOL. XXXIII. No. 45. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, JUNE 30, 1938. $2 PER YEAR GALLAGHER GIFT CHARGE IN ASIA OF RARE BEAUTY New; St. Theresa^s Church at Frederick Concordia, Kans. — (Spe A new $5,500 church at cial)— Official acceptance of Frederick, Weld county, will the resignation of His Excel lency, the Most Rev. Francis be completed in three weeks J. Tief, as Bishop of Concor 'v ^ J .Ji r > s'" ^ "S'S ^ ^ i \ e ^ ■' --r- * and plans have been drawn dia, owing to continued ill for the Gallagher Memorial health for the past few chapel in Mt. Olivet ceme years, has just been received tery, the diocesan Chancery from the Holy See through office announced this week. the Apostolic Delegation. His Both buildings have unusual Excellency has been assigned to features. Construction of the the Titular See of Nisa. This see, $40,000 chapel should be com in Lycia, Southern Asia Minor, was pleted by fall. -

Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Papers and Journal Articles School of Theology 2007 Classified timelines of ernacularv liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy Russell Hardiman University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article Part of the Religion Commons This article was originally published as: Hardiman, R. (2007). Classified timelines of vernacular liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy. Pastoral Liturgy, 38 (1). This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classified Timelines of Vernacular Liturgy: Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy Russell Hardiman Subject area: 220402 Comparative Religious Studies Keywords: Vernacular Liturgy; Pastoral vision of the Second Vatican Council; Roman Policy of a single translation for each language; International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL); Translations of Latin Texts Abstract These timelines focus attention on the use of the vernacular in the Roman Rite, especially developed in the Renewal and Reform of the Second Vatican Council. The extensive timelines have been broken into ten stages, drawing attention to a number of periods and reasons in the history of those eras for the unique experience of vernacular liturgy and the issues connected with it in the Western Catholic Church of our time. The role and function of International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL) over its forty year existence still has a major impact on the way we worship in English. This article deals with the restructuring of ICEL which had been the centre of much controversy in recent years and now operates under different protocols. -

CATHOLICS in WORLD Milillber 400,000,000 Pirrim

CATHOLICS IN WORLD MilillBER 400,000,000 Th* Rcslitci B u th« lnteniatioii41 Ntw* Serrlee (Wlra and HaU), tht N. C. W. C. Ntwa SarTtca (Inclndlns ^ d ios and Cablta) Ita Oira Spaetal Sarrica, Ldman Sarviea of China. Intarcational nioatiatad Nawa. and N. C. W. C. Pictnra Saraica. Listening In Leftists in Spain Local .. Local Near Supreme Court Justice Fer Editioff Edition dinand Pecora of New York Continue sayst “If all the men and Attacks women who commit perjury Double Ranks in courts were sentenced to jail, we would have to build Religion more prisons than there are hotels and apartment houses in this town.” (The Rev. Dr. Joseph F. Thom- well-known authority on Spanish Of Protestants ing and John V. Hinkel went to history and culture. Mr, Hinkel, a An oath, says the Netc CatU' Spain to make a first-hand study graduate of the University of EGISTER (Name Registered in'the U. S. Patent Office) oUc Dictionary, since it con of the religious, social, and eco Notre Dame, is a New ICork news nomic aspects of the Spanish con paperman, and also has been a Islam Closest to .Rome in Total sists in calling upon the /.11- flict. Dr. Thoming is professor keen student of the Spanish situa VOL. XIV. No. 29 DENVER, COLO., SUNDAY, JULY 17, 1938 TWO CENTS knowing and all-truthful f^rod of social history at Mt. St. Mary’s tion.) to witness the truth of a state college, Emmitsburg, Md., and a (By Dr. J oseph F. Thorning and Adherents, Jesuit Monthly ment or the sincerity of a pur J ohn V. -

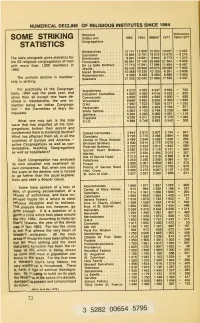

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

![1946-02-18 [P A-5]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9099/1946-02-18-p-a-5-849099.webp)

1946-02-18 [P A-5]

'• Catholic Party Wins Vardaman Denies Part 92 Seats in Belgium In Tampering With D. C. Housing Shortage Forces Entertainment Helps But Lacks Shoe Firm's Records War Wife to Sleep on Floor Wounded in Recovery, Majority The first days of married life in rocco and brought his wife to Wash- th« By Associated Pros last week. is a for a French war bride, ington He violinist. Feb. By Joseph Young Washington BRUSSELS, 18.—Final re- They are staying at the one-room, Tells Aides Commodore James K. Varda- Mrs. Walter J. Leckie, 19, are prov- sults of the Belgian election Sun- kitchenette apartment of his brother Bradley Gen. Omar N. veterans’ day gave the right-wing Catholic! man, Jr., nominated by President ing rugged. She and her husband and sister-in-law. Mr. and Mrs. Hu- Bradley, administrator, told party, pledged to return King Leo- are having to sleep on blankets on bert Leckle—and glad to get it. today special Truman to the Board of Gov- service directors from the 13 pold to his throne, 92 seats in the the floor of a one-room apartment Hubert Leckie knows the problem of branch offices of the Veterans’ Adminis- Chamber of Deputies, but left It ernors of the Federal Reserve at 211 Delaware avenue S.W., where apartment hunting in Washington, tration that could short a majority of the 202 mem- denied be- his brother lives. Adding to Mrs. for he sought a place about four anything they System, categorically do to boost the morale of sick vet- bers. Leckie’s troubles is the fact that months before he obtained his pres- fore a Senate Banking Subcom- erans would their Premier Achille Van Acker’s So- she speaks no English. -

Lasallian Identity According to the Brothers' Formulas of Profession

“T O PROCURE YOUR GLORY ” LASALLIAN IDENTITY ACCORDING TO THE BROTHERS ’ FORMULAS OF PROFESSION 1 MEL BULLETIN N. 54 - December 2019 Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools Secretariat for Association and Mission Editor: Br. Nestor Anaya, FSC [email protected] Editorial Coordinators: Mrs. Ilaria Iadeluca - Br. Alexánder González, FSC [email protected] Graphic Layout: Mr. Luigi Cerchi [email protected] Service of Communications and Technology Generalate, Rome, Italy 2 MEL BULLETINS 54 “T O PROCURE YOUR GLORY ” LASALLIAN IDENTITY ACCORDING TO THE BROTHERS ’ FORMULAS OF PROFESSION BROTHER JOSEAN VILLALABEITIA , FSC 3 INTRODUCTION 4 The Brothers of the Christian Schools, founded by Saint John Baptist de La Salle in 1679, have used different formulas throughout their history to affirm their religious profession. Although the basic structure of them all has faithfully respected the outline proposed by the Founder and the first Brothers in the foundation’s early years (1691-1694), it is no less true that the content included in this permanent context has varied substantially over the years. The most recent change was made, precisely, by the Institute’s penultimate General Chapter in the Spring of 2007. A profession formula is not just any text, at least among Lasallians. Since the beginning, all the essentials of Lasallian consecration, what De La Salle’s followers are and should be, are contained therein: God, other Lasallians (i.e., the community), the school, the poor, the radical nature of its presentation. It is therefore an essential part of our institutional heritage, on which it would be advisable to return more often than we usually do. -

Jean-Baptiste De La Salle from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Jean-Baptiste de La Salle From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Saint John Baptist de La Salle Official portrait of St. John Baptist de La Salle by Pierre Leger (date unknown) Priest and founder Born 30 April 1651 Reims, Champagne, Kingdom of France Died 7 April 1719 (aged 67) Saint-Yon, Normandy, Kingdom of France Honored in Roman Catholic Church Beatified February 19, 1888 Canonized May 24, 1900, by Pope Leo XIII Majorshrine Sanctuary of John Baptist de La Salle, Casa Generalizia, Rome, Italy Feast Church: April 7 May 15 (General Roman Calendar1904-1969, and Lasallian institutions) Attributes stretched right arm with finger pointing up, instructing two children standing near him, books Patronage Teachers of Youth, (May 15, 1950, Pius XII), Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, Lasallian educational institutions, educators, school principals, teachers John Baptist de La Salle (30 April 1651 – 7 April 1719) was a French priest, educational reformer, and founder of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. He is a saint of the Roman Catholic church and the patron saint of teachers. De La Salle dedicated much of his life to the education of poor children in France; in doing so, he started many lasting educational practices. He is considered the founder of the first Catholic schools. Contents [hide] 1 Life and work 2 Sisters of the Child Jesus 3 Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools 4 Veneration 5 Legacy 6 See also 7 References 8 Further reading 9 External links Life and work[edit] De La Salle was born to a wealthy family in Reims, France on April 30, 1651.[1] He was the eldest child of Louis de La Salle and Nicolle de Moet de Brouillet. -

Arundel to Zabi Brian Plumb

Arundel to Zabi A Biographical Dictionary of the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales (Deceased) 1623-2000 Brian Plumb The North West Catholic History Society exists to promote interest in the Catholic history of the region. It publishes a journal of research and occasional publications, and organises conferences. The annual subscription is £15 (cheques should be made payable to North West Catholic History Society) and should be sent to The Treasurer North West Catholic History Society 11 Tower Hill Ormskirk Lancashire L39 2EE The illustration on the front cover is a from a print in the author’s collection of a portrait of Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman at the age of about forty-eight years from a miniature after an oil painting at Oscott by J. R. Herbert. Arundel to Zabi A Biographical Dictionary of the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales (Deceased) 1623-2000 Brian Plumb North West Catholic History Society Wigan 2006 First edition 1987 Second, revised edition 2006 The North West Catholic History Society 11 Tower Hill, Ormskirk, Lancashire, L39 2EE. Copyright Brian Plumb The right of Brian Plumb to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Printed by Liverpool Hope University ‘Some of them left a name behind them so that their praises are still sung, while others have left no memory. But here is a list of generous men whose good works have not been forgotten.’ (Ecclesiasticus 44. 8-10) This work is dedicated to Teresa Miller (1905-1992), of Warrington, whose R.E. -

The Lasallian Tradition and Its Broad Possibilities.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 6, No

Schweigl, Paul. “The Lasallian Tradition and Its Broad Possibilities.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 6, no. 3 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2015). © Paul Schweigl. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. The Lasallian Tradition and Its Broad Possibilities Paul Schweigl, La Salle University, Philadelphia, PA, USA Introduction In 1990, the promulgation of apostolic constitution Ex Corde Ecclesiae by Pope John Paul II intensified discussion over the mission and identity of Catholic institutions of higher learning. Particularly in the United States, where a disproportionately large percentage of such institutions are located, the document and its subsequent implementation by the American bishops were watched with a combination of hopefulness and suspicion. On the one hand, Ex Corde’s assertions that “by its Catholic character, a University is made more capable of conducting an impartial search for truth…that is neither subordinated to nor conditioned by particular interests of any kind” seemed to dovetail nicely with the cherished American academic values of academic freedom and institutional autonomy.2 On the other hand, the document’s mention of the Canon Law requirement that “those who teach theological disciplines in any institute of higher studies have a mandate from the competent ecclesiastical authority”3 seemed a blatant grab for control of classroom content by the hierarchy. The legitimate concerns raised by Ex Corde were mitigated by the productive relationship- building that took place between bishops and university4 administrators in the wake of Ex Corde’s promulgation. -

Of Other Faiths Not Principle of Church in World Relations, Pope Says

/y, i-sÉi * Ai ^, <9 m Official Organ of thc Diocese of Pittsburgh-Founded in 1844 TWO DOLLARS PEE TEA* 110th Year-No. 41 PITTSBURGH, PA., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1953 SINGLE COf^ ITVE CENTS Palish Bishops9 Day of Prayer m .. Oath of Loyally V ' ffisfllsfe w. — For Persecuted Believed Forced Set for Sunday % Vatican City» Dec. a I—A report that the Bishops of Poland have taken a special oath of loyalty to In the Pittsburgh and the Communist regime ruling Po* Greensburg diccteses, and land has not been verified, and, if throughout the United States, true, can only mean that compul- 8 sion was used io exact such an the la|t Sunday of this year, oath, "L'Osservatore Romano," Dec. «7, will be observed a» Vatican City daily, said Saturday. a day ¿of prayer for the Bish- The Communist Warsaw radio had iops, priests and laity: who ar® broadcast the story of the taking victims of persecution.; of the oath on Friday. I' On that day, th^Sso / millioa "ii'Osservatore" said that "con- Catholics in this country are be- ¡1 ditions in Poland are themselves ing asked to Join in prayer that is enough to make us understand that f God will strengthen their perse- the gesture ascribed to the Bishops was not free, but the result of lone cuted brethren, and that light and moral, administrative and physical repentance may be given their per* S violence. The reports that the secutors. Polish Bishops have taken the oath Bishop John F. Dearth of Pitts- must be judged against the back- burgh and Bishop Hughl/L. -

Myanmar Catholic Church Found in Historical Records (1287-1900)

MYANMAR CATHOLIC CHURCH FOUND IN HISTORICAL RECORDS (1287-1900) The most ancient sign of Christianity in Myanmar can be found on the mural painting of Roman and Greek crosses inside Kyansittha cave in Bagan which had been established during the time of Bagan Dynasty (9-13 AD). Nestorians were among the Mongol soldiers who had marched into Bagan in 1287 AD. Basing on this mural it can be said that Christians had set foot on Myanmar soil ever since the end of 13th century. King Min Bin from Rakhine had employed Portuguese soldiers and erected Myuk U or Myo Haung fortress. There were Portuguese mercenary soldiers under the King Tabinshwehtee. They were being accompanied by some Jesuits for their spiritual assistance. Philip de Brito, a Portuguese, reached Rakhine in 1599 and served the King Minrazagyi. He had been delegated by the King to occupy Than Hlyin with guards. He did not fail to offer annual tribute to the Kings of Rakhine and Taungngu. He built a church at Than Hlyin for his conferrers and raised Catholicism. The priests were the Jesuits. In 1613, King Mahadamaraza conquered Than Hlyin, executed de Brito and deported the prisoners of war to Ava. The Catholic prisoners and their descendents were known as “Bayingyi”. In 1721, Fr. Sigis Mondo Calchi, a Barnabite together with Fr. Giuseppe Vittoni arrived from Italy and began their mission in Pegu and Ava. King Taninganwe of Ava, in 1723, invited Fr. S. Calchi to his imperial city, Ava. Fr. S. Calchi’s report, after the audience with the king, to his Superior General in Italy reads; 1 After giving permission to build churches and to preach the Word of God, His Majesty had helped us with donations to build the church.