Lasallian Identity According to the Brothers' Formulas of Profession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule and Foundational Documents

Rule and Foundational Documents Frontispiece: facsimile reproduction of a page—chapter 22, “Rules Concern- ing the Good Order and Management of the Institute”—from the Rule of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the 1718 manuscript preserved in the Rome archives of the Institute. Photo E. Rousset (Jean-Baptiste de La Salle; Icono- graphie, Boulogne: Limet, 1979, plate 52). Rule and Foundational Documents John Baptist de La Salle Translated and edited by Augustine Loes, FSC, and Ronald Isetti Lasallian Publications Christian Brothers Conference Landover, Maryland Lasallian Publications Sponsored by the Regional Conference of Christian Brothers of the United States and Toronto Editorial Board Luke Salm, FSC, Chairman Paul Grass, FSC, Executive Director Daniel Burke, FSC William Mann, FSC Miguel Campos, FSC Donald C. Mouton, FSC Ronald Isetti Joseph Schmidt, FSC Augustine Loes, FSC From the French manuscripts, Pratique du Règlement journalier, Règles communes des Frères des Écoles chrétiennes, Règle du Frère Directeur d’une Maison de l’Institut d’après les manuscrits de 1705, 1713, 1718, et l’édition princeps de 1726 (Cahiers lasalliens 25; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1966); Mémoire sur l’Habit (Cahiers lasalliens 11, 349–54; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1962); Règles que je me suis imposées (Cahiers lasalliens 10, 114–16; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1979). Rule and Foundational Documents is volume 7 of Lasallian Sources: The Complete Works of John Baptist de La Salle Copyright © 2002 by Christian Brothers Conference All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2002101169 ISBN 0-944808-25-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-944808-26-3 (paper) Cover: Portrait of M. -

Profession Class of 2020 Survey

January 2021 Women and Men Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2020 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2020 A Report to the Secretariat of Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations United States Conference of Catholic Bishops January 2021 Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Thomas P. Gaunt, SJ, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6 Institutes Reporting Perpetual Professions .................................................................................... 7 Age of Professed ............................................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to the United States ................................................................. 9 Race and Ethnic Background......................................................................................................... 10 Family Background ....................................................................................................................... -

SECULAR CONSECRATION: Section Two - Chapter One

SECULAR CONSECRATION: Section Two - Chapter One We now come to the heart of what membership in a secular Institute entails, what distinguishes it from other associations of the faithful. It is the full profession of the evangelical councils of celibate chastity, poverty and obedience. Secular institutes are parallel to Religious institutes such as Jesuits and Franciscans in that both profess the evangelical counsels and are recognized by the Church. Other associations may live in the “spirit” of the counsels such as “Third Orders” (often now called “secular orders”) which often creates confusion between them and secular institutes but there are key differences. Third orders do not profess vows and do not commit themselves to lives of celibate chastity. It is the commitment to perpetual celibate chastity that distinguishes Religious or Secular Institutes from of groupings of Christians. Secular and Religious Institutes make vows or similar promises that are morally binding. They place themselves under the Superiors of these Institutes who have real authority over their members that are morally binding. The Code on Canon Law dealing with secular Institutes state that the profession of the counsels in a secular Institute may be made by vow, oath or another recognized expression of consecration. All members of secular institutes must make a binding profession by vow or oath to celibate chastity and make vows or binding promises of poverty and obedience. While not trying to appear excessively juridical it is important to understand that profession in a secular institute entails a full, total and complete consecration of self no less than in vowed Religious life. -

For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 5, No

Sauvage, Michel. “For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 5, no. 2 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2014). © Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association Michel Sauvage, FSC, S.T.D.1 I have been asked to introduce this formation session on Lasallian association. To do that, I must first recall what association meant at the beginning of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. As a foreword to this talk, I would make three points on the parameters of my proposal with regard to the aim of these two days. For you, who are heads of establishments and responsible for educational institutions under a Lasallian trusteeship, this aim is to live out association better today. So, my first point is that I will stick to the meaning of the word association and the realities that it had in the founding experience of John Baptist de La Salle and his first Brothers. I will thus at least go some way to addressing the sub-titles given in the program: History, Origins, Characteristics. It is not possible, however, even to sketch out a development that would relate to another subtitle: “Experiences ‘in the course of history.’” Since I have not studied this question, I am not even certain of fully understanding what it means. -

Life and Works of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux

J&t. itfetnatto. LIFE AND WORKS OF SAINT BERNARD, ABBOT OF CLA1RVAUX. EDITED BY DOM. JOHN MABILLON, Presbyter and Monk of the Benedictine Congregation of S. Maur. Translated and Edited with Additional Notes, BY SAMUEL J. EALES, M.A., D.C.L., Sometime Principal of S. Boniface College, Warminster. SECOND EDITION. VOL. I. LONDON: BURNS & OATES LIMITED. NEW YORK, CINCINNATI & CHICAGO: BENZIGER BROTHERS. EMMANUBi A $ t fo je s : SOUTH COUNTIES PRESS LIMITED. .NOV 20 1350 CONTENTS. I. PREFACE TO ENGLISH EDITION II. GENERAL PREFACE... ... i III. BERNARDINE CHRONOLOGY ... 76 IV. LIST WITH DATES OF S. BERNARD S LETTERS... gi V. LETTERS No. I. TO No. CXLV ... ... 107 PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION. THERE are so many things to be said respecting the career and the writings of S. Bernard of Clairvaux, and so high are view of his the praises which must, on any just character, be considered his due, that an eloquence not less than his own would be needed to give adequate expression to them. and able labourer He was an untiring transcendently ; and that in many fields. In all his manifold activities are manifest an intellect vigorous and splendid, and a character which never magnetic attractiveness of personal failed to influence and win over others to his views. His entire disinterestedness, his remarkable industry, the soul- have been subduing eloquence which seems to equally effective in France and in Italy, over the sturdy burghers of and above of Liege and the turbulent population Milan, the all the wonderful piety and saintliness which formed these noblest and the most engaging of his gifts qualities, and the actions which came out of them, rendered him the ornament, as he was more than any other man, the have drawn him the leader, of his own time, and upon admiration of succeeding ages. -

Travels in America: Aelred Carlyle, His American “Allies,” and Anglican Benedictine Monasticism Rene Kollar Saint Vincent Archabbey, Latrobe, Pennsylvania

Travels in America: Aelred Carlyle, His American “Allies,” and Anglican Benedictine Monasticism Rene Kollar Saint Vincent Archabbey, Latrobe, Pennsylvania N FEBRUARY 1913, Abbot Aelred Carlyle and a majority of the Benedictine monks of Caldey Island, South Wales, renounced the Anglican Church and converted to I Roman Catholicism.1 For years, the Caldey Island monastery had been a show piece of Anglo-Catholicism and a testimony to the catholic heritage of the Anglican Church, but when Charles Gore, the Bishop of Oxford, tried to regularize their status within Anglicanism by forcing Carlyle and the monks to agree to a series of demands which would radically alter their High Church liturgy and devotions, the monks voted to join the Church of Rome. The demands of the Great War, however, strained the fragile finances of the island monastery, and during the spring of 1918, Abbot Carlyle traveled to America to solicit funds for his monastery. “And it was indeed sheer necessity that took me away from the quiet shores of Caldey,” he told the readers of Pax, the community’s magazine, but “Caldey has suffered grievously through the war.”2 Abbot Carlyle saw a possible solution to his problems. “In our need we turned to our Catholic Allies in the United States, and my duty seemed obvious that I should accept the invitation I had received to go to New York to plead in person the cause of Caldey there.” Carlyle had not forgotten lessons from the past. During his years as an Anglican monk, the American connection proved to be an important asset in the realization of his monastic dreams. -

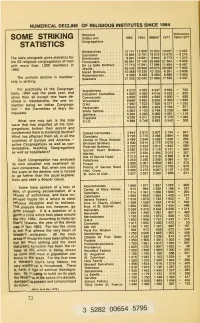

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Superiors General 1952-1988 Brothers Josaphat 1952-1964 Iii

BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 I II SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 III BROTHERS OF THE SACRED HEART SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 Br. Bernard Couvillion, S.C. ROME 2015 IV SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 V INTRODUCTION With great joy I present to all the partners in our mission – brothers, laypeople, and others – the history of our Superiors Gen- eral during the period from 1952 to 1988: Brothers Josaphat (Joseph Vanier), Jules (Gaston Ledoux), Maurice Ratté and Jean- Charles Daigneault. This history is meant as a remembrance, a grateful recognition, and an encouragement. In the first place, it is meant as a remem- brance, profoundly rooted in our spirit and in our heart, full of es- teem toward each one of them. We remember them especially for their human and spiritual greatness and their closeness to God. We recall their remarkable service of authority in the animation of their brothers and in the revitalization of the prophetic mission of our In- stitute on behalf of young people, particularly those most in need. Calling to mind the lives and the works of our brothers, we thank the God of all goodness for the magnificent gifts which he placed in each of them. In doing so, we recognize the evangelical wisdom of our protagonists, who throughout their life knew how to multiply the talents they had received. Our brothers experienced the joy of feeling loved by God. He wanted them to know the depth of his divine love toward all hu- manity and toward each one of them personally. -

Identity and Mission of the Religious Brother in the Church

CONGREGATION FOR INSTITUTES OF CONSECRATED LIFE AND SOCIETIES OF APOSTOLIC LIFE IDENTITY AND MISSION OF THE RELIGIOUS BROTHER IN THE CHURCH "And you are all brothers" (Mt 23:8) Vatican, October 4th, 2015 Feast of Saint Francis of Assisi 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Brother 2. To whom is this document addressed? 3. A framework for our reflection 4. Outline of this Document 1. RELIGIOUS BROTHERS IN THE CHURCH-COMMUNION "I have chosen you as a covenant of the people" (Is 42:6) 5. Putting a face on the covenant 6. In communion with the People of God 7. A living memorial for the Church’s awareness 8. Rediscovering the common treasure 9. A renewed project 10. Developing the common treasure 11. Brother: a Christian experience from the beginning 2. THE IDENTITY OF RELIGIOUS BROTHER: A mystery of communion for mission 12. Memory of the love of Christ: "The same thing you must do ..." (Jn 13:14-15) I. THE MYSTERY: BROTHERHOOD, THE GIFT WE RECEIVE 13. Witness and mediator: "We believe in the love of God" 14. Consecrated by the Spirit 15. Public commitment: making the face of Jesus-brother visible today 16. Exercise of the baptismal priesthood 17. Like all his brothers in all things 18. Profession: a unique consecration, expressed in different vows 19. An incarnated and unifying spirituality 20. A spirituality of the Word in order to live the Mystery "at home" with Mary II. COMMUNION: BROTHERHOOD, THE GIFT WE SHARE 21. From the gift we receive to the gift we share: "That they be one so that the world may believe" (Jn 17:21) 22. -

A New Consecration?

62 A NEW CONSECRATION? By ALFRED DE BONHOME ~HE LEADING document of Vatican Council II on the nature I! of the Church brought into prominence an aspect of their state of life with which most religious were entirely ~ unfamiliar: that their profession of the evangelical counsels was integral to the consecration common to all Christians-- sacramental baptism. In fact, before Lumen Gentium had been promulgated, Pope Paul VI had declared: So it is that the profession of the evangelical vows is added to the consecration which is proper to the baptized. One may call it a special kind of consecration which is the fulfilment of baptism, in that, by means of this consecration, Christ's faithful commit themselves wholly to God to such an extent that their dedication puts their entire lives at his disposal. 1 The question thus arises whether this consecration of those who make profession of the evangelical counsels is something new, in addition to their baptismal consecration. 2 One of the key-texts of the dogmatic Constitution on the Church reads as follows: Through vows or other sacred bonds which of their nature are similar to those vows, certain of Christ's faithful take on the obligations of the three evangelical counsels, and are wholly given over to God, their supreme love, as his slaves. In this way they are taken into God's service, for his glory, by a new and speciaI title. Indeed, they are already dead to sin and consecrated to God through baptism . (but) they are more intimately consecrated to his worship. -

The Constitution and the Statutes

The Constitution and the Statutes of the Swiss-American Benedictine Congregation Established by the General Chapter Changes Approved by CIVC – September 21, 2005 and summer 2008 Contents Preface Section I: Of the Nature and Purpose of the Congregation C 1-5 Section II: Norms for the Individual Monasteries A. Of the Organs of Government of the Monastery C 6-8; S 1-5 1. Of the Chapter C 9-10; S 6-10 2. Of the Abbot C 11-20; S 11-26 3. Of the Council C 21-23; S 27-29 4. Of Delegated Authority C 24-25; S 30-31 B. Of Order in the Community S 32-33 C. Of Claustral and Secular Oblates S 34-35 D. Of Novitiate and Profession, and of the Juniors C 26; S 36 1. Of the Novitiate C 27-31; S 37-41 2. Of Profession and the Temporarily Professed C 32-38; S 42-43 3. Of the Effects and Consequences of the Vows a. Stability, and Fidelity to the Monastic Way of Life C 39-42 b. Obedience C 43 c. Consecrated Celibacy C44 d. Poverty and the Sharing of Goods C 45-46; S 44-46 E. Of the Component Elements of Monastic Life 1. Of Common Prayer and the Common Life C 47-49; S 47-48 2. Of Private Prayer and Monastic Asceticism C 50-52; S 49 3. Of Work and Study C 53-54; S 50 4. Of Penalties and Appeals C 55-57; S 51-52 5. Of Financial Administration S 53-56 6. -

Poverty, Chastity, and Obedience

Poverty, Chastity, and Obedience The Big Three Poverty. Chastity. Obedience. There they are: the “big three.” According to canon law, every member of a religious order must profess publicly these three vows (canon 654). My congregation, the De La Salle Christian Brothers, requires its members to profess two vows special to the order: to associate for service of poor people through education, and to ensure stability in the institute. The first special vow calls the brothers to associate and to strive constantly to make their schools and educational works accessible to those who are poor. This is the work not of a single brother but of a community of brothers and Lasallians who together make this happen. This vow challenges all Lasallians to serve economically disadvantaged people in all schools, including those that enroll students from the middle and upper classes. The vow of stability reminds the brothers to be faithful to their worldwide institute and to its members and traditions. Stability is a fitting response to the faithfulness of God, who guides the global institute to serve as a stable force in the life of hundreds of thousands of young people. Other congregations may also have particular vows, but the bottom line for nuns and monks, sisters and brothers, and priests who are members of a religious order (i.e., Jesuits or Dominicans) is the three fundamental vows. Fundamental is a good word to describe them, because the vows touch almost every meaningful aspect of life. How is a vow different from a promise? The difference is similar to how discerning differs from deciding.