Contesting Modernity in Sayyid Qutb and Ali Shariati's Islamic Revival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Politics

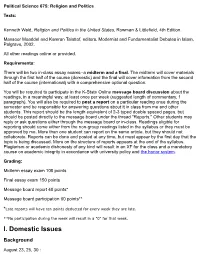

Political Science 675: Religion and Politics Texts: Kenneth Wald, Religion and Politics in the United States, Rowman & Littlefield, 4th Edition. Mansoor Moaddel and Kamran Talattof, editors, Modernist and Fundamentalist Debates in Islam, Palgrave, 2002. All other readings online or provided. Requirements: There will be two in-class essay exams--a midterm and a final. The midterm will cover materials through the first half of the course (domestic) and the final will cover information from the second half of the course (international) with a comprehensive optional question. You will be required to participate in the K-State Online message board discussion about the readings, in a meaningful way, at least once per week (suggested length of commentary, 1 paragraph). You will also be required to post a report on a particular reading once during the semester and be responsible for answering questions about it in class from me and other students. This report should be the length equivalent of 2-3 typed double spaced pages, but should be posted directly to the message board under the thread "Reports." Other students may reply or ask questions either through the message board or in-class. Readings eligible for reporting should come either from the non-group readings listed in the syllabus or they must be approved by me. More than one student can report on the same article, but they should not collaborate. Reports can be done and posted at any time, but must appear by the first day that the topic is being discussed. More on the structure of reports appears at the end of the syllabus. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Sayyid Qutb: an Historical and Contextual Analysis of Jihadist Theory Joseph D

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 4-7-2008 Sayyid Qutb: An Historical and Contextual Analysis of Jihadist Theory Joseph D. Bozek Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Bozek, Joseph D., "Sayyid Qutb: An Historical and Contextual Analysis of Jihadist Theory" (2008). Masters Theses. 672. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/672 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sayyid Qutb: An Historical and Contextual Analysis of Jihadist Theory By Joseph D. Bozek School of Criminal Justice Grand Valley State University Sayyid Qutb: An Historical and Contextual Analysis of Jihadist Theory By Joseph D. Bozek August 7, 2008 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master’s of Science in Criminal Justice in the School of Criminal Justice of Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids, Ml Thesis Committee Dr. Jonathan White (Chair) Dr. William Crawley Dr. Frank Hughes Acknowledgements To the faculty and staff of Grand Valley State University’s School of Criminal Justice to whom I am truly grateful for all of the support and guidance both inside and outside of the classroom. I hope I can one day impact someone’s life in the same way you have impacted mine. 11 Abstract The purpose of this research is to provide a comprehensive analysis of a salient jihadist philosopher by the name of Sayyid Qutb. -

The Battle Between Secularism and Islam in Algeria's Quest for Democracy

Pluralism Betrayed: The Battle Between Secularism and Islam in Algeria's Quest for Democracy Peter A. Samuelsont I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 309 f1. BACKGROUND TO THE ELECTIONS AND THE COUP ................................ 311 A. Algeria's Economic Crisis ......................................... 311 B. Algeria's FirstMultiparty Elections in 1990 for Local Offices ................ 313 C. The FIS Victory in the 1991 ParliamentaryElections ...................... 314 D. The Coup dt& tat ................................................ 318 E. Western Response to the Coup ...................................... 322 III. EVALUATING THE LEGITIMACY OF THE COUP ................................ 325 A. Problems Presented by Pluralism .................................... 326 B. Balancing Majority Rights Against Minority Rights ........................ 327 C. The Role of Religion in Society ...................................... 329 D. Islamic Jurisprudence ............................................ 336 1. Islamic Views of Democracy and Pluralism ......................... 337 2. Islam and Human Rights ...................................... 339 IV. PROBABLE ACTIONS OF AN FIS PARLIAMENTARY MAJORITY ........................ 340 A. The FIS Agenda ................................................ 342 1. Trends Within the FIS ........................................ 342 2. The Process of Democracy: The Allocation of Power .................. 345 a. Indicationsof DemocraticPotential .......................... 346 -

American Muslims: a New Islamic Discourse on Religious Freedom

AMERICAN MUSLIMS: A NEW ISLAMIC DISCOURSE ON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By John C. R. Musselman, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 13, 2010 AMERICAN MUSLIMS: A NEW ISLAMIC DISCOURSE ON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM John C. R. Musselman, B.A. Mentor: Chris Seiple, Ph.D. ABSTRACT In 1998, the U.S. government made the promotion of religious freedom official policy. This policy has often been met with skepticism and hostility from foreign governments and publics. In the Muslim-majority world, it is commonly seen as an attempt to discredit traditional cultural norms and/or Islamic law, as covert support for American missionary activity, and/or as cultural imperialism. American Muslims could play a key role in changing this perception. To date, the American Muslim community has not become deeply invested in the movement for international religious freedom, but their notable absence has not been treated in any substantial length. This thesis draws on the disciplines of public policy, political science, anthropology, and religious studies to explore this absence, in the process attempting to clarify how the immigrant Muslim American community understands religious freedom. It reviews the exegetical study of Islamic sources in relation to human rights and democracy by three leading American Muslim intellectuals—Abdulaziz Sachedina, M.A. Muqtedar Khan, and Khaled Abou El Fadl—and positions their ideas within the dual contexts of the movement for international religious freedom movement and the domestic political incorporation of the Muslim American community. -

Not for Distribution

6 The decline of the legitimate monopoly of violence and the return of non-state warriors Cihan Tuğal Introduction For the last few decades, political sociology has focused on state-making. We are therefore quite ill equipped to understand the recent rise of non-state violence throughout the world. Even if states still seem to perform more violence than non- state actors, the latter’s actions have come to significantly transform relationships between citizens and states. Existing frameworks predispose scholars to treat non-state violence too as an instrument of state-building. However, we need to consider whether non-state violence serves other purposes as well. This chapter will first point out how the post-9/11 world problematises one of sociology’s major assumptions (the state’s monopolisation of legitimate violence). It will then trace the social prehistory of non-state political violence to highlight continui- ties with today’s intensifying religious violence. It will finally emphasise that the seemingly inevitable rise of non-state violence is inextricably tangled with the emergence of the subcontracting state. Neo-liberalisation aggravates the practico- ethical difficulties secular revolutionaries and religious radicals face (which I call ‘the Fanonite dilemma’ and ‘the Qutbi dilemma’). The monopolisation of violence: social implications War-making, military apparatuses and international military rivalry figure prominently in today’s political sociology. This came about as a reaction to the sociology and political science of the postwar era: for quite different rea- sons, both tended to ignore the influence of militaries and violence on domestic social structure. Political science unduly focused on the former and sociology on the latter, whereas (according to the new political sociology) international violence and domestic social structure are tightly linked (Mann 1986; Skocpol 1979; Tilly 1992). -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

Revolution in Bad Times

asef bayat REVOLUTION IN BAD TIMES ack in 2011, the Arab uprisings were celebrated as world- changing events that would re-define the spirit of our political times. The astonishing spread of these mass uprisings, fol- lowed soon after by the Occupy protests, left observers in Blittle doubt that they were witnessing an unprecedented phenomenon— ‘something totally new’, ‘open-ended’, a ‘movement without a name’; revolutions that heralded a novel path to emancipation. According to Alain Badiou, Tahrir Square and all the activities which took place there—fighting, barricading, camping, debating, cooking and caring for the wounded—constituted the ‘communism of movement’; posited as an alternative to the conventional liberal-democratic or authoritar- ian state, this was a universal concept that heralded a new way of doing politics—a true revolution. For Slavoj Žižek, only these ‘totally new’ political happenings, without hegemonic organizations, charismatic leaderships or party apparatuses, could create what he called the ‘magic of Tahrir’. For Hardt and Negri, the Arab Spring, Europe’s indignado protests and Occupy Wall Street expressed the longing of the multitude for a ‘real democracy’, a different kind of polity that might supplant the hopeless liberal variety worn threadbare by corporate capitalism. These movements, in sum, represented the ‘new global revolutions’.1 ‘New’, certainly; but what does this ‘newness’ tell us about the nature of these political upheavals? What value does it attribute to them? In fact, just as these confident appraisals were being circulated in the us and Europe, the Arab protagonists themselves were anguishing about the fate of their ‘revolutions’, lamenting the dangers of conservative restora- tion or hijacking by free-riders. -

Islamic Movements Syllabus

Islamic Movements Tugrul Keskin Portland State University 1. Course Overview This course will review and analyze the increasing trend of Islamic movements (IM) and Islamic parties (IP) around the world in the global age of capitalism and the contemporary Muslim world. In the course, we focus on IM and IP and their relationship with global capitalism, democracy, free speech, human rights, inequality, colonialism/imperialism, modernity, secularism and governance. All of these concepts are directly related with the conditions of modernity which have been created by the free market economy; therefore, I perceive Political Islam (IM and IP) as a product of modern conditions, such as urbanization, the emergence of a manufacture-based economy, the increased availability of higher education, women’s participation in education and the workforce, and the elimination of traditional social values. The conditions of modernity created the concept of democracy in the modern world. Christianity and Judaism have consequently been struggling to redefine themselves under the new rules and regulations – not revelations - for over 200 years; whereas in Muslim Societies, the conditions of modernity challenge Islam and Muslims. Therefore, Muslims will be forced to decide between the expression and practice of Din/Religion and the material world in their daily life. There is therefore an ongoing struggle between the observance of God and the pursuit of material conditions. Although Political Islam could be seen as a direct reaction to modern politics, Islam is actually an inherently political religion that rules and regulates every aspect of a believer’s daily life, much in the same way as economic conditions do. -

Qu™B Al-Din Al-Shirazi Iii 15

STUDIES ON QU™B AL-DIN AL-SHIRAZI III 15 QU™B AL-DIN AL-SHIRAZI (D. 710/1311) AS A TEACHER: AN ANALYSIS OF HIS IJAZAT (STUDIES ON QU™B AL-DIN AL-SHIRAZI III)1 BY REZA POURJAVADY & SABINE SCHMIDTKE Qu†b al-Din al-Shirazi, who had reached the peak of his scholarly career at the turn of the 8th/14th century, was in close contact with most of the leading scholars of his time throughout his life, be it as teachers, colleagues, associates or students. In the introduction to his commentary on Ibn Sina’s (d. 428/1037) Qanun, he included some details about his childhood and early education, particularly in the field of medicine.2 In his Durrat al-taj, he relates that he was initiated into Sufism by his father, Δiyaˆ al-Din Mas¨ud b. al-MuÒliÌ al-Kaziruni, who invested him with the “habit of benediction” (khirqat al-tabarruk) at the age of ten, and that he received the “habit of aspiration” (khirqat al-irada) at the age of thirty from MuÌyi al-Din AÌmad b. ¨Ali b. Abi l-Ma¨ali.3 During 1 This article is part of a series of studies devoted to Qu†b al-Din al-Shirazi. “Studies on Qu†b al-Din al-Shirazi I” was published in Journal Asiatique 292 (2004), pp. 309-328 (“Qu†b al-Din al-Shirazi’s (d. 710/1311) Durrat al-taj and Its Sources”); “Studies on Qu†b al-Din al-Shirazi II” was published in Studia Iranica 36 (2007), pp. -

Practical Sufism an Akbarian Foundation for a Liberal Theology of Difference

0≤°£¥©£°¨ 3µ¶©≥≠ !Æ !´¢°≤©°Æ &صƧ°¥©ØÆ ¶Ø≤ ° ,©¢•≤°¨ 4®•Ø¨Øßπ ض $©¶¶•≤•Æ£• by Vincent Cornell Among the criticisms leveled at the Sufi tradition by its modern Muslim opponents, two stand out as most prominent. The first is that Sufism does not represent authentic Islam. This is allegedly because its teachings do not come directly from the Qur'an, the Prophet Muhammad, and the first generations of Muslims ( al-Salaf al-Salih ). According to this "Salafi" argument, Sufism is a Trojan horse for unwarranted innovations that owe their origins to non-Muslim civilizations such as Greece, Persia, and India. The Salafi polemic began early in the history of Sufism, and is often associated with the anti-Sufi arguments of Hanbali scholars, such as Ibn al-Jawzi (d.1201) in Talbis Iblis or Ibn Taymiyya (d.1328) in his critiques of Ibn 'Arabi.[ 1] It was given a new lease on life in the twentieth century by the modernist reformer Muhammad Rashid Rida (d.1935), who edited Ibn Taymiyya's works and influenced later Salafi ideologues such as Hasan al-Banna (d.1949), the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood.[ 2] Although Banna saw some value in what he called "pure" Sufism, he condemned the Sufi tradition as a whole for incorporating foreign ideas, such as "the sciences of philosophy and logic and the heritage and thought of ancient nations". As a result, he asserted, "Wide gaps were opened for every atheist, apostate, and corrupter of opinion and faith to enter by the door in the name of Sufism."[ 3] In the generation after Banna's death, Salafi modernism, represented by the Muslim Brotherhood and allied groups such as Pakistan's Jamaat-i Islam, contracted a marriage of convenience with Salafi traditionalism, represented by the Wahhabi sect of Saudi Arabia. -

A Study on Sayyid Qutb a Dissertation Submitted To

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO READING A RADICAL THINKER: A STUDY ON SAYYID QUTB A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY LAITH S. SAUD CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2017 Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. iii Chapter One: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Biography ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter Review .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter Two: Reading Qutb Theologically; Toward a Method for Reading an Islamist ............................................................................................................................................................................ 10 The Current State of Inquiries on Qutb: The Fundamentalist par excellence ............................. 11 Theology, Epistemology, and Logic: Toward a Methodology .............................................................. 17 What is Qutb’s General Cosmology? .............................................................................................................