HR.Orders.5P 503-566

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Movements: 1968, 1981 and 1997 the Impact Of

Student Movements: 1968, 1981 and 1997 The impact of students in mobilizing society to chant for the Republic of Kosovo Atdhe Hetemi Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of East European Languages and Cultures Supervisor Prof. dr. Rozita Dimova Department of East European Languages and Cultures Dean Prof. dr. Gita Deneckere Rector Prof. dr. Rik Van de Walle October 2019 i English Summary This dissertation examines the motives and central visions of three student demonstrations, each taking place within different historical and political contexts and each organized by a different generation of Kosovo Albanian students. The years 1968, 1981 and 1997 witnessed a proliferation of student mobilizations as collective responses demanding more national rights for Albanians in Kosovo. I argue that the students' main vision in all three movements was the political independence of Kosovo. Given the complexity of the students' goal, my analysis focuses on the influence and reactions of domestic and foreign powers vis-à-vis the University of Prishtina (hereafter UP), the students and their movements. Fueled by their desire for freedom from Serbian hegemony, the students played a central role in "preserving" and passing from one generation to the next the vision of "Republic" status for Kosovo. Kosova Republikë or the Republic of Kosovo (hereafter RK) status was a demand of all three student demonstrations, but the students' impact on state creation has generally been underestimated by politicians and public figures. Thus, the primary purpose of this study is to unearth the various and hitherto unknown or hidden roles of higher education – then the UP – and its students in shaping Kosovo's recent history. -

Haradinaj Et Al. Indictment

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA CASE NO: IT-04-84-I THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST RAMUSH HARADINAJ IDRIZ BALAJ LAHI BRAHIMAJ INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, pursuant to her authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, charges: Ramush Haradinaj Idriz Balaj Lahi Brahimaj with CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY and VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OR CUSTOMS OF WAR, as set forth below: THE ACCUSED 1. Ramush Haradinaj, also known as "Smajl", was born on 3 July 1968 in Glodjane/ Gllogjan* in the municipality of Decani/Deçan in the province of Kosovo. 2. At all times relevant to this indictment, Ramush Haradinaj was a commander in the Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës (UÇK), otherwise known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). In this position, Ramush Haradinaj had overall command of the KLA forces in one of the KLA operational zones, called Dukagjin, in the western part of Kosovo bordering upon Albania and Montenegro. He was one of the most senior KLA leaders in Kosovo. 3. The Dukagjin Operational Zone encompassed the municipalities of Pec/Pejë, Decani/Deçan, Dakovica/Gjakovë, and part of the municipalities of Istok/Istog and Klina/Klinë. As such, the villages of Glodjane/Gllogjan, Dasinovac/Dashinoc, Dolac/Dollc, Ratis/Ratishë, Dubrava/Dubravë, Grabanica/Grabanicë, Locane/Lloçan, Babaloc/Baballoq, Rznic/Irzniq, Pozar/Pozhare, Zabelj/Zhabel, Zahac/Zahaq, Zdrelo/Zhdrellë, Gramocelj/Gramaqel, Dujak/ Dujakë, Piskote/Piskotë, Pljancor/ Plançar, Nepolje/Nepolë, Kosuric/Kosuriq, Lodja/Loxhë, Barane/Baran, the Lake Radonjic/Radoniq area and Jablanica/Jabllanicë were under his command and control. -

The Mujahedin in Nagorno-Karabakh: a Case Study in the Evolution of Global Jihad

The Mujahedin in Nagorno-Karabakh: A Case Study in the Evolution of Global Jihad Michael Taarnby 9/5/2008 WP 20/2008 The Mujahedin in Nagorno-Karabakh: A Case Study in the Evolution of Global Jihad Michael Taarnby Summary The current volume of publications dealing with Islamist militancy and terrorism defies belief in terms of its contents. The topic of this paper is a modest attempt to direct more attention and interest towards the much overlooked sub-field of historical research within Jihadi studies. Introduction The current volume of publications dealing with Islamist militancy and terrorism defies belief in terms of its contents. This can be perceived as part of a frantic effort to catch up for the lack of attention devoted to this phenomenon during the 1980s and 1990s, when this field of research field was considerably underdeveloped. The present level of research activity is struggling to keep pace with developments. Thus, it is primarily preoccupied with attempting to describe what is actually happening in the world right now and possibly to explain future developments. This is certainly a worthwhile effort, but the topic of this paper is a modest attempt to direct more attention and interest towards the much overlooked sub-field of historical research within Jihadi studies. The global Jihad has a long history, and everyone interested in this topic will be quite familiar with the significance of Afghanistan in fomenting ideological support for it and for bringing disparate militant groups together through its infamous training camps during the 1990s. However, many more events have been neglected by the research community to the point where most scholars and analysts are left with an incomplete picture, that is most often based on the successes of the Jihadi groups. -

Molim Da Svedok Sada Pročita Svečanu Izjavu. SVEDOK JOVIĆ

UTORAK,UTORAK, 18. NOVEMBAR 18. NOVEMBAR 2003. 2003. / SVEDOK / SVEDOK BORISAV B-1524 JOVIĆ (pauza) SUDIJA MEJ: Molim da svedok sada pročita svečanu izjavu. SVEDOK JOVIĆ: Svečano izjavljujem da ću govoriti istinu, celu istinu i ništa osim istine. SUDIJA MEJ: Izvolite sedite. GLAVNO ISPITIVANJE: TUŽILAC NAJS TUŽILAC NAJS – PITANJE: Hoćete li da nam kažete svoje ime i prezime, molim vas? SVEDOK JOVIĆ – ODGOVOR: Borisav Jović. TUŽILAC NAJS – PITANJE: Gospodine Joviću, ja ću sada da prepričam kakvi su bili vaši kontakti sa Tužilaštvom da biste identifikovali materijal na kojem smo radili. Prvo, u smislu konteksta, vi ste se rodili oktobra 1928. godine i bili ste na raznim funkcijama u vladi tokom vaše karijere. Uglavnom ste se bavili socijalnim i ekonomskim razvojem, bili ste ambasador u Italiji (Italy) krajem sedamdesetih godina. Da li ste 1989. godine bili izabrani kao srpski predstavnik u Predsedištvo SFRJ, da li ste bili potpredsednik tog Predsedni- štva od 5. maja 1989. godine do 15. maja 1990. godine. Da li ste bili pred- sednik od 15. maja 1990. do 15. maja 1991. godine? Da li ste posle toga bili predsednik Socijalističke partije Srbije od 24. maja 1991. godine do oktobra 1992. godine kada ste preuzeli funkciju od optuženog koji je tada sišao sa te funkcije i kad se on vratio kao vođa partije da li ste vi onda postali potpred- sednik stranke i ostali na toj funkciji do novembra 1995. godine? SVEDOK JOVIĆ – ODGOVOR: Da, tačno je to. TUŽILAC NAJS – PITANJE: Dakle, imajući to na umu, da li je tačno da ste vi napisali dve knjige od kojih se jedna zove ‘’Poslednji dani SFRJ’’, to je dnev- nik, a druga se zove ‘’Knjiga o Miloševiću’’? Da li ste takođe imali razgovor kao osumnjičeni sa Tužilaštvom u septembru 2002. -

Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, and FUTURE by Andrew Watkins

PEACEWORKS Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, AND FUTURE By Andrew Watkins NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 Making Peace Possible NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines the phenomenon of insurgent fragmentation within Afghanistan’s Tali- ban and implications for the Afghan peace process. This study, which the author undertook PEACE PROCESSES as an independent researcher supported by the Asia Center at the US Institute of Peace, is based on a survey of the academic literature on insurgency, civil war, and negotiated peace, as well as on interviews the author conducted in Afghanistan in 2019 and 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Andrew Watkins has worked in more than ten provinces of Afghanistan, most recently as a political affairs officer with the United Nations. He has also worked as an indepen- dent researcher, a conflict analyst and adviser to the humanitarian community, and a liaison based with Afghan security forces. Cover photo: A soldier walks among a group of alleged Taliban fighters at a National Directorate of Security facility in Faizabad in September 2019. The status of prisoners will be a critical issue in future negotiations with the Taliban. (Photo by Jim Huylebroek/New York Times) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Kosovo Killers. Part 1 by Aleksander Kots, Dmitry Stepshin, Kosmopolskaya Gazeta

May 14, 2008 Kosovo killers. Part 1 By Aleksander Kots, Dmitry Stepshin, Kosmopolskaya Gazeta http://www.kp.ru/daily/24096.5/324917/ After Kosovo declared independence, Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) Carla Del Ponte raucously quit her position at The Hague. She slammed the door so loudly behind her that the ceiling plaster cracked at parliaments across the European Union. After her exile to Argentina as Switzerland's ambassador, Ponte said the new Kosovo was run by butchers who made a fortune trafficking organs extracted from kidnapped Serbs. In her book titled, "The Hunt: Me and the War Criminals," Ponte describes how a black organ market formed during the Kosovo War. Meanwhile, she says, the European Union played dumb paying no attention to the crimes. KP journalists went to Kosovo to learn more about the crimes. Iron Carla's revelation Hardly a day goes by without fragments of Ponte's book hitting Belgrade newspapers. Here is a commonly quoted section that details the horrors of Kosovo organ trafficking: "According to the journalists' sources, who were only identified as Kosovo Albanians, some of the younger and fitter prisoners were visited by doctors and were never hit. They were transferred to other detention camps in Burrel and the neighboring area, one of which was a barracks behind a yellow house 20 km behind the town. "One room inside this yellow house, the journalists said, was kitted out as a makeshift operating theater, and it was here that surgeons transplanted the organs of prisoners. These organs, according to the sources, were then sent to Rinas airport, Tirana, to be sent to surgical clinics abroad to be transplanted to paying patients. -

An Overview of the Development of Mitrovica Through the Years This Publication Has Been Supported by the Think Tank Fund of Open Society Foundations

An overview of the development of Mitrovica through the years This publication has been supported by the Think Tank Fund of Open Society Foundations. Prepared by: Eggert Hardten 2 AN OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF MITROVICA THROUGH THE YEARS CONTENTS Abbreviations .............................................................................................................4 Foreword .....................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................7 2. The Historical Dimension – Three Faces of Mitrovica .......................................8 2.1. War ...............................................................................................................8 2.2 Trade ............................................................................................................9 2.3. Industry .......................................................................................................10 2.4. Summary .....................................................................................................12 3. The Demographic Dimension ................................................................................14 3.1. Growth and Decline .....................................................................................14 3.2. Arrival and Departure .................................................................................16 3.3. National vs. Local -

Annex 4: Mechanisms in Europe

ANNEX 4: MECHANISMS IN EUROPE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Conflict Background and Political Context The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) emerged from World War II as a communist country under the rule of President Josip Broz Tito. The new state brought Serbs, Croats, Bosnian Muslims, Albanians, Macedonians, Montenegrins, and Slovenes into a federation of six separate republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia) and two autonomous provinces of Serbia (Kosovo and Vojvodina). Ten years after Tito’s death in 1980, the country was in economic crisis and the mechanisms he had designed to both repress and balance ethnic demands in the SFRY were under severe strain. Slobodan Milošević had harnessed the power of nationalism to consolidate his power as president of Serbia. The League of Communists of Yugoslavia dissolved in January 1990, and the first multiparty elections were held in all Yugoslav republics, carrying nationalist parties to power in Bosnia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Macedonia.1763 Meanwhile, Milošević and his political allies asserted control in Kosovo, Vojvodina, and Montenegro, giving Serbia’s president de facto control over four of the eight votes in the federal state’s collective presidency. This and the consolidation of Serbian control over the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA) heightened fears and played into ascendant nationalist feelings in other parts of the country. Declarations of independence by Croatia and Slovenia on June 25, 1991, brought matters to a head. Largely homogenous Slovenia succeeded in defending itself through a 10-day conflict that year against the Serb-dominated federal army, but Milošević was more determined to contest the independence of republics with sizeable ethnic Serb populations. -

Introduction

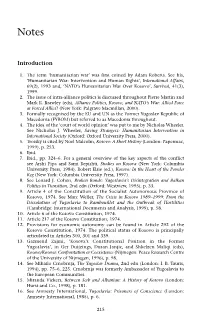

Notes Introduction 1. The term ‘humanitarian war’ was first coined by Adam Roberts. See his, ‘Humanitarian War: Intervention and Human Rights’, International Affairs, 69(2), 1993 and, ‘NATO’s Humanitarian War Over Kosovo’, Survival, 41(3), 1999. 2. The issue of intra-alliance politics is discussed throughout Pierre Martin and Mark R. Brawley (eds), Alliance Politics, Kosovo, and NATO’s War: Allied Force or Forced Allies? (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000). 3. Formally recognised by the EU and UN as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) but referred to as Macedonia throughout. 4. The idea of the ‘court of world opinion’ was put to me by Nicholas Wheeler. See Nicholas J. Wheeler, Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). 5. Trotsky is cited by Noel Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History (London: Papermac, 1999), p. 253. 6. Ibid. 7. Ibid., pp. 324–6. For a general overview of the key aspects of the conflict see Arshi Pipa and Sami Repishti, Studies on Kosova (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), Robert Elsie (ed.), Kosovo: In the Heart of the Powder Keg (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997). 8. See Lenard J. Cohen, Broken Bonds: Yugoslavia’s Disintegration and Balkan Politics in Transition, 2nd edn (Oxford: Westview, 1995), p. 33. 9. Article 4 of the Constitution of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, 1974. See Marc Weller, The Crisis in Kosovo 1989–1999: From the Dissolution of Yugoslavia to Rambouillet and the Outbreak of Hostilities (Cambridge: International Documents and Analysis, 1999), p. 58. 10. Article 6 of the Kosovo Constitution, 1974. -

Fate of the Missing Albanians in Kosovo

Humanitarian Law Center Research, Dokumentation and Memory Fate of the Missing Albanians in Kosovo The report was composed on the basis of the statements given by witnesses and family members of the missing persons, data and observations of the Humanitarian Law Center (HLC) Monitors who regularly followed the exhumation and autopsies of the bodies found in the mass graves in Serbia, as well as data on bodies that were identified and handed over, received from the families or Belgrade War Crimes Chamber Investigative Judge who signs the Record on Identified Mortal Remains Hand Over. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) information, missing persons’ family members [Albanians, Serbs, Montenegrins, Bosniacs, Roma, Egyptians, and Ashkalis] reported to this organization disappearance of 5,950 persons in relation to the armed conflicts in Kosovo. Meanwhile, the fate of 3,462 persons has been revealed and there were 2,488 persons left on the List of the Missing Persons prepared by ICRC by 15 November 2005. According to the HLC’s information, there are 1,785 missing Albanians, 538 Serbs, and 165 persons of other nationalities. Until 15 November 2005, the Republic of Serbia handed over 615 identified Albanian bodies and 14 mortuary bags with unidentified mortal remains to the UNMIK Office for Missing Persons and Forensics [OMPF] and three bodies to the US authorities since those bodies found in the mass graves in Serbia belonged to the US citizens. Serbian Ministry of Interiors [MUP] formed the concealed mass graves in Serbia in order to conceal traces of war crimes committed in Kosovo. -

Curriculum Vitae – Karim Khan LLB (Hons) (Lond), AKC (Lond), Fsiarb, Fciarb, Dip

Curriculum vitae – Karim Khan LLB (Hons) (Lond), AKC (Lond), FSIArb, FCIArb, Dip. Int.Arb. (CIArb) Barrister-at-Law What the Directories say: “A “superb lawyer” and “frighteningly clever master strategist,” who has represented clients in international courts across the world. As a prosecutor for the ICTY and ICTR, he has vast experience of handling complex matters such as crimes against humanity, war crimes and contempt of court disputes.”; “His ability to address and sum up the most complicated legal analysis in concise yet powerful words has become legendary.”; “A very highly rated advocate who is a real force to be reckoned with. He fights his cases hard but honourably”; “Has superior knowledge of international law and is a world-class advocate and drafter. He has the ability to cut to the heart of a legal issue and identify possible solutions with precision and speed. Karim manages large teams without any drop-off in the high level of service provided, and is a fierce advocate.” Chambers and Partners Legal Directory (extracts, 2016-2020) “He ensures he has a very deep knowledge of not just the facts of an incident but of all aspects of a case, which in this field involves politics, culture and society.” Legal 500 (2021) “Leading Silk”, Ranked Tier 1, “International crime & Extradition KARIM AHMAD KHAN QC is currently serving as Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, having been appointed by the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, as the first Special Adviser and Head of the Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Da’esh /ISIL crimes (UNITAD) pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2379 (2017).