Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party - Introduction

(Updated on January 12, 2005) Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party - Introduction More than a decade after the fall of the former Soviet Union and Eastern European communist regimes, the international communist movement has been spurned worldwide. The demise of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is only a matter of time. Nevertheless, before its complete collapse, the CCP is trying to tie its fate to the Chinese nation, with its 5000 years of civilization. This is a disaster for the Chinese people. The Chinese people must now face the impending questions of how to view the CCP, how to evolve China into a society without the CCP, and how to pass The Epoch Times is now publishing a special editori al series, on the Chinese heritage. The Epoch Times is “Nine Commentaries on the Chinese Communist Party.” now publishing a special editorial series, “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party.” Before the lid is laid on the coffin of the CCP, we wish to pass a final judgment on it and on the international communist movement, which has been a scourge to humanity for over a century. Throughout its 80-plus years, everything the CCP has touched has been marred with lies, wars, famine, tyranny, massacre and terror. Traditional faiths and principles have been violently destroyed. Original ethical concepts and social structures have been disintegrated by force. Empathy, love and harmony among people have been twisted into struggle and hatred. Veneration and appreciation of the heaven and earth have been replaced by an arrogant desire to “fight with heaven and earth.” The result has been a total collapse of social, moral and ecological systems, and a profound crisis for the Chinese people, and indeed for humanity. -

Sun Yatsen Seeking a Newer China (Library of World Biography Series) 1St Edition Download Free

SUN YATSEN SEEKING A NEWER CHINA (LIBRARY OF WORLD BIOGRAPHY SERIES) 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David B Gordon | 9780321333063 | | | | | Sun Yat-sen The political institutions of modern China. The — Sino-Japanese War was a disastrous defeat for the Qing government, feeding into calls for reform. Although Charles Soong had been a personal friend of Sun's, he was enraged when Sun announced his intention to marry Ching-ling because while Sun was a Christian he kept two wives, Lu Muzhen and Kaoru Otsuki ; Soong viewed Sun's actions as running directly against their shared religion. Stanford University Press. His conversion to Christianity was Sun Yatsen Seeking a Newer China (Library of World Biography Series) 1st edition to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement. Although he was a baptized Christian, he was first buried at a Buddhist shrine near Beijing called the Temple of Azure Clouds. Retrieved 7 May Part of the speech was made into the National Anthem of the Republic of China. He soon went to exile in Japan for safety but returned to found a revolutionary government Sun Yatsen Seeking a Newer China (Library of World Biography Series) 1st edition the South as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. This full collaboration was called the First United Front. First United Front. In the midst of the chaos, Sun Yat-sen married his third wife, Soong Ching-ling m. ANU publishing. Myers Ramon Hawley. San Francisco District Office. Premier of the Kuomintang of China — Sun Yat-sen remains unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for having a high reputation both in mainland China and in Taiwan. -

Images of Power

IMAGES OF POWER: CHINESE YUAN and MING DYNASTIES: FOCUS (Chinese Decorative Arts and the Forbidden City) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy.org/huma nities/art-asia/imperial-china/yuan- dynasty/v/david-vases ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy.org/huma nities/art-asia/imperial-china/yuan- dynasty/a/chinese-porcelain- production-and-export TITLE or DESIGNATION: The David Vases CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Chinese Yuan Dynasty DATE: 1351 C.E. MEDIUM: white porcelain with cobalt-blue underglaze ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy.org/ partner-content/asian-art- museum/aam- China/v/forbidden-city ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/43 9 TITLE or DESIGNATION: Forbidden City CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Chinese Ming Dynasty DATE: 15th century C.E. and later LOCATION: Beijing, China TITLE or DESIGNATION: Guan Yu Captures General Pang De Artist: Shang Xi CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Mughal Dynasty DATE: c. 1430 C.E. MEDIUM: hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk IMAGES OF POWER: CHINESE YUAN and MING DYNASTIES: SELECTED TEXT (Chinese Decorative Arts and the Forbidden City) The emperors of the Yuan dynasty were Mongols, descendants of Ghenghis Khan (1162-1227), the “Universal Leader” as his name translates. Ghenghis had conquered part of northern China in 1215, having already united the various nomadic tribes of the steppe land. He divided his empire into four kingdoms, each ruled and expanded by a son and his wife. Ghenghis' grandson, Kublai Khan (reigned 1260-94), was ruler of the eastern Great Khanate. He completed the conquest of China by defeating the Southern Song in 1279. -

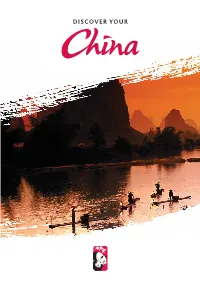

Discover Your 2 Welcome

DISCOVER YOUR 2 WELCOME Welcome to China Holidays We were immensely proud to be a Queen’s Award winner. We are an independently owned and managed company, founded in 1997, specialising in providing beset value travel arrangements to China only. Therefore we can offer you a highly personalised service with my colleagues in London and Beijing working hard to ensure you have an unforgettable, high quality and value-for-money holiday. It is because of our dedication to providing this that we have managed to prosper in one of the most competitive industries in the world. For thousands of years China has been the mysterious Middle Kingdom, the fabled land Welcome to my homeland and between heaven and earth, steeped in legends, the land of my ancestors. I almost enthralling travellers and explorers who undertook the most gruelling journeys to discover for envy those of you who have not themselves this exotic civilisation. Nowadays, yet been to China as the surprises travelling is easier but the allure of China remains and pleasures of my country are the same. We at China Holidays have the in-depth understanding, knowledge and passion needed still yours to discover, whilst for to create some of the best journeys by bringing those of you who have already been, together authentic cultural experiences and there are still so many more riches imaginative itineraries, combined with superb service and financial security. to savour – the rural charms of the minority villages in the west, sacred On the following pages you will find details of our new and exciting range of China Holidays, ranging mountains inhabited by dragons and from classic itineraries to in-depth regional journeys gods, nomadic life on the grasslands and themed holidays, which mix the ever-popular of Tibet and Inner Mongolia, along sights with the unusual. -

Early German Research in Ancient Chinese Architecture (1900–1930)

Eduard Kögel: Early German Research in Ancient Chinese Architecture (1900–1930). 1 Berliner Chinahefte/Chinese History and Society 2011, Nr.39, p.81–91. Early German Research in Ancient Chinese Architecture (1900–1930) Architectural history in China Architecture was seen as a handicraft in China until the early 20th century. This craft was documented in building manuals and passed down from generation to generation of carpenter families (Chiu Che Bing 2008). Traditional Chinese scholars were engaged in all aspects of art, but only marginally in architecture. Western-based architectural education was introduced into China during the 1920s, and only afterwards was architectural history established as an academic field of study (Xing 2002).1 Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt writes: “In truth, architectural history in China in the first decades of the twentieth century was perceived as a primarily literary endeavour, interesting because of the challenge of making one’s way through difficult texts, not because the actual structures were inherently inspiring.”2 Today the history of architecture is an integral part of architecture education, but faculties of art history that focus on architectural history are still very rare (Shatzman Steinhardt 2002). Foreign scholars first started conducting scientific research on ancient Chinese architecture in the early 20th century, before Chinese historians started to concentrate on the topic. In the following paper, I will focus on the status of knowledge in Germany concerning Chinese architecture up to the early 1930s, when the Beijing-based Society for Research in Chinese Architecture (Zhonggo Yingzao Xueshe) discovered new insights by studying ancient buildings on site. The most important German scholar in the first phase of the 20th Century was Ernst Boerschmann (1873–1949), but besides him various architects and art historians also contributed to the discourse in the West with publications almost always written in German. -

Tailor-Made China | Japan| Far East South Korea | Taiwan |Mongolia | Central Asia Tailor-Made Holidays by Transindus

Tailor-made China | Japan Far| South Korea | Taiwan East | Mongolia | Central Asia TRANSINDUS.COM Tailor-made holidays by TransIndus Welcome to TransIndus t seems barely a week goes by without some programme a single vegetable on sale. Nor the goosebumps I felt when about the Far East dominating the airwaves these days. I came across a traditional Japanese wedding party at a IMichael Wood’s dazzling overview of Chinese history, live park in Tokyo – the silk kimono and white face of the bride coverage of the New Year celebrations from Harbin and Hong glowing against a futuristic backdrop of skyscrapers. The Kong, and a fabulous series from the BBC on China’s wildlife other-worldy atmosphere of a Taoist mountain shrine; the have all served to remind us how diverse this part of the world fabulous intricacy of a mosaic-encrusted Timurid dome rising is, and what great potential it holds for travellers. Which is from the midst of a Silk Road city; and the elegant simplicity why we at TransIndus felt it high time we join the fray and of a wooden farmstead in the hills of South Korea. In Europe, bring our brochure for the region up to date, showcasing some such treasures would be vestiges of a dimly remembered of the new and exciting destinations that have opened up past. But in the East, they’re part of living traditions – with since we published our last one. astonishingly ancient roots. To which end, we’ve spent the past few months setting down Sharing such discoveries and translating them into enjoyable accounts of the places we’ve found most compelling in our holidays for our guests are among the most enriching own recent travels, and searching for photographs to do them aspects of our job. -

China Delight

Friendly Planet Travel China Delight China OVERVIEW Introduction These days, it's quite jarring to walk around parts of old Beijing. Although old grannies can still be seen pushing cabbages in rickety wooden carts amidst huddles of men playing chess, it's not uncommon to see them all suddenly scurry to the side to make way for a brand-new BMW luxury sedan squeezing through the narrow hutong (a traditional Beijing alleyway). The same could be said of the longtang-style alleys of Sichuan or a bustling marketplace in Sichuan. Modern China is a land of paradox, and it's becoming increasingly so in this era of unprecedented socioeconomic change. Relentless change—seen so clearly in projects like the Yangtze River dam and the relocation of thousands of people—has been an elemental part of China's modern character. Violent revolutions in the 20th century, burgeoning population growth (China is now the world's most populous country by far) and economic prosperity (brought about by a recent openness to the outside world) have almost made that change inevitable. China's cities are being transformed—Beijing and Shanghai are probably the most dynamic cities in the world right now. And the country's political position in the world is rising: The 2008 Olympics were awarded to Beijing, despite widespread concern about how the government treats its people. China has always been one of the most attractive travel destinations in the world, partly because so much history exists alongside the new, partly because it is still so unknown to outsiders. The country and its people remain a mystery. -

Beijing Travel Eguide

Travel eGuides ® the world at your fingertips … Beijing, China Beijing eGuide.com Introduction Beijing, the capital of China is a vibrant, modern city with a strong culture and heritage. Beijing provides much for the visitor to experience and enjoy. For the traveller, Beijing is a welcoming city offering a wide variety options. Combining the heritage of an ancient history with the excitement of a rapidly growing metropolis, Beijing has something for every mood or interest. Fans of culture can enjoy a performance of the classic Beijing Opera, a Kung Fu show, Beijing acrobatics, or a night at one of the city's many theatres or cinemas. Those looking for nightlife will enjoy the already large and constantly growing list of Beijing restaurants and bars. From the Forbidden City to the Great Wall, Tiananmen Square to the bird's nest Olympic Stadium, there is an endless list of things to see in and around Beijing. In fact, there is so much to do that it is easy for the traveller to become overwhelmed. Fortunately, there are many opportunities to relax. Whether you sit in one of the many parks or temples, spend the afternoon over a pot of tea or indulge in a famous Beijing massage, there are just as many was to do nothing in Beijing as there are activities. Some of the main attractions are Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden City, the Great Wall, Beihai Park, the Summer Palace, the Temple of Heaven, Fragrant Hill, the Peking Man, the Big Bell Temple, the Ming Tombs, the Lugou Bridge and the Grand View Garden. -

32.LAGERWEY, John. “Introduction,” Modern Chinese Religion I Song

Introduction John Lagerwey These volumes, like those that preceded them on early Chinese religion and those that will follow in part two of the present project, are focused on a period of paradigm shift. The basic hypothesis is that, between 960 when the Song and 1368 when the Ming was founded, something radically new emerged that, by becoming state orthodoxy, determined what was to come. The consensus has long been that that something new is Daoxue 道學 or neo-Confucianism, concerning which there is no reason to contest Yu Ying-shih’s characterization: From a historical point of view, the emergence of the Tao-hsüeh commu- nity in Sung China may be most fruitfully seen as a result of seculariza- tion. There is much evidence suggesting that the Tao-hsüeh community was, in important ways, modeled on the Ch’an monastic community. The Neo-Confucian academy, from structure to spirit, bears a remarkable family resemblance to the Ch’an monastery. But the difference is sub- stantial and important. Gradually, quietly, but irreversibly, Chinese soci- ety was taking a this-worldly turn with Ch’an masters being replaced by Confucian teachers as spiritual leaders.1 But the emergence of this orthodoxy needs at the very least to be contextual- ized, for if Chan 禪 influences Daoxue, it is also in competition with Tiantai 天台, and Buddhism and Daoism continue both to borrow from and to com- pete with each other. Under the influence of both esoteric Buddhism 密宗 and Daoist Neidan 內丹 (symbolic alchemy), Tiantai Buddhism and Zhengyi 正一 (Orthodox Unity) Daoism produce vast ritual syntheses that not only trans- form the relationship between them and medium-based popular religion but continue to define their respective ritual traditions right down to the present. -

Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party - Introduction

(Updated on January 12, 2005) Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party - Introduction More than a decade after the fall of the former Soviet Union and Eastern European communist regimes, the international communist movement has been spurned worldwide. The demise of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is only a matter of time. Nevertheless, before its complete collapse, the CCP is trying to tie its fate to the Chinese nation, with its 5000 years of civilization. This is a disaster for the Chinese people. The Chinese people must now face the impending questions of how to view the CCP, how to evolve China into a society without the CCP, and how to pass The Epoch Times is now publishing a special editorial series, on the Chinese heritage. The Epoch Times is “Nine Commentaries on the Chinese Communist Party.” now publishing a special editorial series, “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party.” Before the lid is laid on the coffin of the CCP, we wish to pass a final judgment on it and on the international communist movement, which has been a scourge to humanity for over a century. Throughout its 80-plus years, everything the CCP has touched has been marred with lies, wars, famine, tyranny, massacre and terror. Traditional faiths and principles have been violently destroyed. Original ethical concepts and social structures have been disintegrated by force. Empathy, love and harmony among people have been twisted into struggle and hatred. Veneration and appreciation of the heaven and earth have been replaced by an arrogant desire to “fight with heaven and earth.” The result has been a total collapse of social, moral and ecological systems, and a profound crisis for the Chinese people, and indeed for humanity. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Plates 9 Introduction 25 Sources and research 34 Preparation and research concept 38 The education of Ernst Boerschmann and his early work for the military 38 Heinrich Hildebrand and the documentation of the Temple of Enlightenment (1891–1897) 43 Joseph Dahlmann and religion in the Far East 47 Boerschmann’s memorandum about research in Chinese architecture (1905) 49 Karl Bachem and the German Reichstag 50 The Temple of Azure Clouds 52 Fritz Jobst at Jietai Temple (1905) 65 Franz Baltzer and Japanese architecture 68 Architecture and the religious culture of the Chinese 72 Field trips in China (1906–1909) 74 On the way to China (1906) 74 First winter in Beijing (1906–1907) 75 Trip to the Eastern Qing Tombs (March–April 1907) 86 Trip to Chengde (May–June 1907) 91 Beijing and the Western Hills (June–August 1907) 102 From the Western Qing Tombs to Mount Wutai (August–September 1907) 115 From Shanxi to Shandong Province (September–December 1907) 128 Trip to Zhejiang (December 1907–Spring 1908) 157 Mount Putuo (January 1908) 174 Jiangsu Province (Spring 1908) 187 The great trip to the West: Taiyuan, Shanxi Province (April–May 1908) 196 From Pingyao to Mengcheng, Shanxi Province (May 1908) 207 Feng Shui pillars and towers for Kui Xing in Shanxi Province 223 From sacred Mount Hua to Xi’an, Shaanxi Province (June 1908) 228 From Fengxian to Mianxian, Shaanxi Province (July 1908) 241 From Guangyuan to Chengdu, Sichuan Province (July–August 1908) 247 From Dujiangyan to sacred Mount Emei and Leshan, Sichuan