Trust in Self-Driving Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Transportation in China and the United States Yuming Ge, Xiaoman Liu, Libo Tang, and Darrell M

DECEMBER 2017 Smart transportation in China and the United States Yuming Ge, Xiaoman Liu, Libo Tang, and Darrell M. West INTRODUCTION It is no surprise that countries are suffering traffic problems as their rural and suburban populations move to cities and population density increases around urban areas. As cities grow in density, we have seen vehicular congestion, poor urban planning, and insufficient highway designs. The unfortunate downsides of these trends are the loss of lives due to accidents, time and money spent commuting, and lost productivity and economic growth for the system as a whole. All these developments are problematic because transportation accounts for six to 12 percent of Gross Domestic Product in many developed countries.1 The cost of traffic congestion alone is estimated to be greater than $200 billion in four Western countries: France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States.2 But the good news is that recent advancements in computing, network speed, and communications sensors make it possible to improve transportation infrastructure, traffic management, and vehicular operations. Through better infrastructure, ubiquitous connectivity, 5G (fifth generation) networks, Yuming Ge, Xiaoman Liu, and dynamic traffic signals, remote sensors, vehicle-sharing services, and autonomous vehicles, it is Libo Tang are researchers at the possible to increase automotive safety, efficiency, and operations. Connected vehicles are moving China Academy beyond crash notification and lane changing guidance to offer a variety of services related to main- of Information and Communication tenance, operations, and entertainment. 5G networks will enable a shift in cellular technology from Technology (CAICT). supporting fixed services to communication and data exchange that is machine-based. -

Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: Implications for Policy and Practice in City and Transportation Planning

Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: Implications for Policy and Practice in City and Transportation Planning by Charles Ng supervised by Laura Taylor A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada December 8, 2017 Acknowledgments This paper could not have been completed without the help and support of the caring individuals that I am thankful to have in my life. I would like to thank and acknowledge my mother, Maria, and my sister, Ka Lang for providing me with love and support; my advisor, Peter Timmerman, and my supervisor, Laura Taylor, for providing me with academic and non-academic support; and my invaluable friends that I have made in the MES program for their encouragement, support and relief. i Foreword My Area of Concentration for my Plan of Study is sustainable transportation planning for growth management. Connected and Autonomous Vehicles will change the urban landscape, the roles of governments and present new challenges to planners. This paper has allowed me to view transportation planning through the lens of emerging technologies and how this affects cities in the short and long term. There are many sustainability and growth management implications with Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. For example, automated vehicles can foster decentralization because it easily enables travel however, if utilized correctly, automated vehicles can also compliment local transit systems to support intensification. This is especially important in Ontario (Canada’s first province to allow testing of autonomous vehicles on public roads) as it directly relates to the goals and policies related to sprawl and sustainability as outlined in Ontario’s four provincial land use plans: The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH), The Greenbelt Plan, The Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan and the Niagara Escarpment Plan. -

2016 WP Transformation of the Workplace Through Robotics, AI And

The Transformation of the Workplace Through Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and Automation: Employment and Labor Law Issues, Solutions, and the Legislative and Regulatory Response January 2016 AUTHORS Garry Mathiason Michael Lotito Robert Wolff Natalie Pierce Kerry Notestine Greg Brown John Cerilli Eugene Ryu Joon Hwang Phil Gordon Ilyse Schuman Miranda Mossavar Paul Kennedy Paul Weiner Sarah Ross Theodora Lee William Hays Weissman Jeff Seidle IMPORTANT NOTICE This publication is not a do-it-yourself guide to resolving employment disputes or handling employment litigation. Nonetheless, employers involved in ongoing disputes and litigation will find the information extremely useful in understanding the issues raised and their legal context. This report is not a substitute for experienced legal counsel and does not provide legal advice or attempt to address the numerous factual issues that inevitably arise in any employment-related dispute. Copyright ©2016 Littler Mendelson, P.C. All material contained within this publication is protected by copyright law and may not be reproduced without the express written consent of Littler Mendelson. Table of Contents SECTION / TOPIC PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Legal Challenges Arising from Robotics, Artificial Intelligence 1 and Automation B. A Note on the Important Concepts Addressed in This Report 2 II. ROBOTICS, AUTOMATION, AND THE NEW WORKPLACE LANDSCAPE (CATEGORY ONE) 3 A. Job Dislocation and Job Creation 4 1. WARN Act 4 2. Severence 4 3. Retraining 5 B. Labor Unions and Collective Bargaining 5 1. Protected Concerted Activity 5 2. Collective Bargaining 6 C. Tax Implications 7 D. Anti-Discrimination 8 1. Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA) 8 2. -

Recent Developments in the Automation of Cars

International Journal of Technical Research and Applications e-ISSN: 2320-8163, www.ijtra.com Volume 5, Issue 1 (Jan-Feb, 2017), PP. 95-100 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE AUTOMATION OF CARS- A REVIEW 1Mrudul Amritphale, 2Abhishek Mahesh, 3Ashwini Motiwale, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Acropolis Institute of Technology and Research Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India [email protected] Abstract— Vehicular automation can be defined as the use of assistance systems (ADAS) are engineered to eliminate the technology in a vehicle in such a way that it can assist the driver physical as well as the psychological after-effects of a in the best possible way by reducing his/her mental stresses. The collision by eliminating the possibilities of causing the present world is accepting the rapid changes in the technology collision. In the 21st century, various automobile companies and trying to apply it in the real world. Hence, the automobile are focusing on applying the newly advanced intelligent industry is keenly interested in improvising with the dynamic features of a vehicle by using the new technology. Modern day systems in their cars, in order to assist the drivers while cars such as Mercedes Benz S-class, BMW 7 series etc. are driving as well as to safeguard the passengers travelling in the equipped with such automated systems. Vehicles at present are cars, systems such as adaptive cruise control, advanced semi-automated: fully automated vehicles are under development automatic collision notification, intelligent parking assistant and testing and will take time to be available commercially. system, automatic parking, precrash system, traffic sign Passengers comfort and wellbeing, increased safety and increased recognition, distance control assist, dead man’s switch, anti- highway capacity are among the most important initiatives lock braking system(ABS) and many more. -

Accelerating the Transition to Zevs in Shared and Autonomous Fleets

Accelerating the transition to ZEVs in shared and autonomous fleets December 4, 2018 Table of contents Executive summary 5 1 Introduction 8 2 Background 10 Electromobility 10 Shared passenger mobility models 11 Shared electric passenger fleets 11 Vehicular automation 12 Barriers to adoption 13 3 Review of implications for low-carbon transportation 15 ZEVs 15 Shared 16 Autonomous 18 ZEV + shared 19 ZEV + autonomous 20 Shared + autonomous 20 ZEV + shared + autonomous 20 4 Electromobility in shared mobility fleets 22 Vehicle type 22 Profiles of users and riders of shared use mobility 22 Profiles of users and riders of shared use ZEVs & opportunities for acceleration 23 Challenges 23 Reasons for adopting BEVs in shared mobility 25 Logistics, operations of BEVs within shared use mobility 26 Trip distance 26 Daily vehicle kilometers traveled and parking time 27 BEV range and charging needs 28 5 Practicality and business case for BEVs in shared use mobility 30 Cost of ownership and BEV value proposition in car sharing 30 Cost of ownership and BEV value proposition in ride hailing 31 6 Shared electromobility deployment conclusions 35 Key success factors 35 Lessons learned 35 Policies that support electromobility in shared use fleets 36 Concluding remarks 38 Appendices A. Growth of shared mobility services 40 B. List of ZEV shared mobility services 41 C. Impacts of ride hailing 44 D. Example of BEV car sharing education tools 45 E. Uber ZEV-related communications 46 F. BEV in ride hailing payback, Montréal and London 48 Accelerating the Transition to ZEVs in Shared and Autonomous Fleets 2 List of figures and tables List of figures Figure 1. -

2014 Automated Vehicles Symposium Proceedings

2014 Automated Vehicles Symposium Proceedings 2014 Automated Vehicle Symposium – Synopsis of Proceedings DISCLAIMER The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the speakers and contributors to the Automated Vehicle Symposium and not necessarily those of the United States Department of Transportation. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade names manufacturers’ names or specific products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. 2014 Automated Vehicles Symposium Proceedings—Final December 2014 Publication Number: FHWA-JPO-14-176 Prepared by: Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, MA 02142 Prepared for: Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology 1200 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20590 2 Acknowledgments The 2014 Automated Vehicles Symposium (AVS 2014) was produced through a partnership between the Association of Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) and Transportation Research Board (TRB), and is indebted to its many volunteer contributors and speakers who developed the symposium content, produced sessions, and contributed to the development of these proceedings. AVS 2014 also benefitted from the direct financial contributions of its commercial benefactors, and the institutional support of the many companies and agencies that supported the time, travel, and participation for their staff. The organizing committee gratefully acknowledges the United States Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office (ITS JPO) for the level of its support to AVS 2014 and for these proceedings. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Digital Business für Verkehr und Mobilität Ist die Zukunft autonom und digital? Hrsg.: Johann Höller, Tanja Illetits-Motta, Stefan Küll, Ursula Niederländer, Martin Stabauer 2020 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Ein (digitales) Buch über den Verkehr 2 Trust in Self-Driving Technology 3 Fahrerlose U-Bahnen: 30 Jahre Vorsprung im Öffentlichen Verkehr 4 Augmented Reality (AR) in PKWs 5 Sharing Economy – Vom Produkt zum Service am Beispiel Verkehrsmobilität 6 Personalisierte Mobilität 7 Connected Cars – Profiteure, Risiken und Geschäftsfelder 8 Blockchain und ihre Anwendungen in der Mobilität 9 Urbahne Seilbahnen 10 Potentiale des E-Scooter Sharing-System 11 Last Mile EIN (DIGITALES) BUCH ÜBER DEN VERKEHR? Johann Höller Teil 1 von Digital Business für Verkehr und Mobilität Ist die Zukunft autonom und digital? Institut für Digital Business 2020 Digital Business für Verkehr und Mobilität Ist die Zukunft autonom und digital? Herausgeber: Johann Höller; Tanja Illetits-Motta; Stefan Küll; Ursula Niederländer; Martin Stabauer ISBN: 978-3-9504630-4-0 (eBook) 2020 Johannes Kepler Universität Institut für Digital Business A-4040 Linz, Altenberger Straße 69 https://www.idb.edu/ Detailliertere bibliographische Daten, weitere Beiträge, sowie alternative Formate finden Sie unter https://www.idb.edu/publications/ Bildquelle Titelbild: https://pixabay.com/photos/ebook-tablet-touch-screen-read- 3106983/ Dieser Beitrag unterliegt den Bestimmungen der Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung- Keine Bearbeitung 4.0 International-Lizenz. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ -

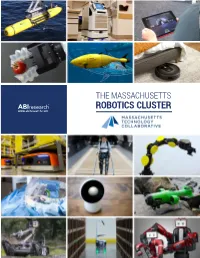

Robotics Cluster the Massachusetts Robotics Cluster

THE MASSACHUSETTS ROBOTICS CLUSTER www.abiresearch.com THE MASSACHUSETTS ROBOTICS CLUSTER Dan Kara Research Director, Robotics ABI Research Phil Solis Research Director ABI Research Photo Credits: Amazon Robotics: www.amazonrobotics.com, Aquabotix Technology: www.aquabotix.com, Bluefin Robotics: www.bluefinrobotics.com, Boston Engineering: www.boston-engineering.com, Corindus Vascular Robotics: www.corindus.com, Endeavor Robotics: www.endeavorrobotics.com, iRobot: www.irobot.com, Jibo: www.jibo.com, Locus Robotics: www.locusrobotics.com, Neurala: www.neurala.com, Rethink Robotics: www.rethinkrobotics.com, ReWalk Robotics: www.rewalk.com, Robai: www.robai.com, Softrobotics: www.softroboticsinc.com, Vecna Technologies: www.vecna.com I www.abiresearch.com THE MASSACHUSETTS ROBOTICS CLUSTER TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CONTRIBUTORS ....................................................................................................1 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................2 3. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................7 3.1. INNOVATION ECONOMY ...............................................................................................7 3.2. STRATEGIC APPROACH ...................................................................................................7 4. ROBOTS AND ROBOTICS TECHNOLOGIES ......................................................9 4.1. AUTONOMY ....................................................................................................................9 -

Low-Speed Automated Vehicles (Lsavs) in Public Transportation (2021)

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/26056 SHARE Low-Speed Automated Vehicles (LSAVs) in Public Transportation (2021) DETAILS 124 pages | 8.5 x 11 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-26210-1 | DOI 10.17226/26056 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Kelley Coyner, Shane Blackmer, John Good, Mobilitye3, LLC and Paul Lewis, Alice Grossman, Eno Center for Transportation; Transit Cooperative Research Program; Transportation Research Board; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and FIND RELATED TITLES Medicine SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021. Low-Speed Automated Vehicles (LSAVs) in Public Transportation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26056. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Low-Speed Automated Vehicles (LSAVs) in Public Transportation TRANSIT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM TCRP RESEARCH REPORT 220 Low-Speed Automated Vehicles (LSAVs) in Public Transportation Kelley Coyner Shane Blackmer John Good MOBILITYE3, LLC Arlington, VA Paul Lewis Alice Grossman ENO CENTER FOR TRANSPORTATION Washington, DC Subject Areas Public Transportation • Passenger Transportation • Planning and Forecasting Research sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration in cooperation with the Transit Development Corporation 2021 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Social and Economic Impacts of Autonomous Shuttles for Collective Transport: an In- Depth Benchmark Study Fabio Antonialli, Danielle Attias

Social and economic impacts of Autonomous Shuttles for Collective Transport: an in- depth benchmark study Fabio Antonialli, Danielle Attias To cite this version: Fabio Antonialli, Danielle Attias. Social and economic impacts of Autonomous Shuttles for Collective Transport: an in- depth benchmark study. Paper Development Workshop – RBGN, May 2019, Madrid, Spain. hal-02489808v2 HAL Id: hal-02489808 https://hal-centralesupelec.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02489808v2 Submitted on 18 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Social and economic impacts of Autonomous Shuttles for Collective Transport: an in- depth benchmark study Fabio Antonialli & Danielle Attias1 Abstract: Most of current managerial studies on Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) focus on future social and economic impacts of privately-owned AVs. In contrast, the present study aimed on carrying out an in-depth benchmark on successful experimentations with Autonomous Shuttles for Collective Transport (ASCTs), identifying the most relevant social and economic findings as well as understanding how such results may contribute to future projects and trials. The research was designed as an in-depth qualitative benchmark of exploratory and descriptive nature on three selected European projects with ASCTs: CityMobil2, GATEway, SHOJOA. -

Self Driving Car: Artificial Intelligence Approach

2012 Jurnal TICOM Vol.1 No.1 September Self Driving Car: Artificial Intelligence Approach Ronal Chandra*1, Nazori Agani*2, Yoga Prihastomo*3 *Postgraduate Program, Master of Computer Science, University of Budi Luhur Jl. Raya Ciledug, Jakarta 12260 Indonesia [email protected], 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] Abstract - Artificial Intelligence also known as (AI) is the capability of a machine to function as if the machine has the capability to think like a human. In automotive industry, AI plays an important role in developing vehicle technology. Vehicular automation involves the use of mechatronics and in particular, AI to assist in the control of the vehicle, thereby relieving responsibilities from the driver or making a responsibility more manageable. Autonomous vehicles sense the world with such techniques as laser, radar, lidar, Global Positioning System (GPS) and computer vision. In this paper, there are several methodologies of AI techniques such as: fuzzy logic, neural network and swam intelligence which often used by autonomous car. On the other hand, self driving cars are not in widespread use, but their introduction could produce several direct advantages: fewer crashes, reduce oil consumption and air pollution, elimination of redundant passengers, etc. So that, in future where everyone can use a car and change the way we use our highways. Key Words - artificial intelligence, self driving, vehicular automation, fuzzy logic, neural network, swam intelligence. I. INTRODUCTION optimally support the driver in his monitoring and decision making process, efficient human-machine AI brings a new paradigm in the automotive world. interfaces play an important part. -

Autonomous Vehicles: a Perspective of Past and Future Trends

International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research IJETSR www.ijetsr.com ISSN 2394 – 3386 Volume 4, Issue 10 October 2017 Autonomous VEHICLEs: A Perspective of Past and Future Trends Aditya Bhat, B.E Mechanical (Pursuing) MIT College Of Engineering, Kothrud, Pune ABSTRACT: This paper provides an overview of the advancement in the automobile technology in the recent years for the society. We have come a long way from development of the manual zero automation vehicles to developing vehicles with smart systems. With technological advancement, automotive manufacturers are investing in development of smart cars, driverless processes, pre-collision technologies that deliver fuel-efficient and safe mobility solutions. Companies such as Ford, Mercedes and Tesla are front runners to build autonomous vehicles for a drastically changing consumer world The main cause of most vehicular accidents today is driver error. Alcohol, drugs, speeding, aggressive driving,inexperience, slow reaction time and ignoring road conditions are the major factors. Hence it has become a necessity to use artificial intelligence to avoid accidents, have safer and smarter modes of transport and there will be no loss of life and property.With the rise of technological giants like TESLA and GOOGLE, the research in the field of intelligent cars has increased multifold in the past decade. We have now been able to produce cars which use intelligent systems that control the vehicle and the driver monitors the vehicle operation. With further advancement in ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE it will be possible to manufacture a fully autonomous driverless smart car which can be used under all road and environmental conditions.