Support from Self-Determination Theory and Positive Psychology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Person-Centred Therapy Vs. Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy

PERSON-CENTRED THERAPY VS. RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY The purpose of this paper is to present a brief comparison of the approach to psychotherapy of Carl Rogers and Albert Ellis. I have selected Albert Ellis for comparative purposes since he was one of the other therapists participating with Rogers in the film “Three Approaches to Psycotherapy” , made in 1964, centering on interviews with the client “Gloria”. Person-Centered Therapy Rogers first formulated the essentials of Person-Centered Therapy (PCT), an approach to helping individuals and groups in conflict, in 1940. At the time it was a revolutionary hypothesis that a self-directed growth process would follow the provision and reception of a particular kind of relationship characterized by genuineness, non-judgmental caring, and empathy. Its most fundamental and pervasive concept is trust. The foundation of Rogers’ approach is a human being’s actualizing tendency towards the realization of his or her full potential; which he described as a formative tendency observable in the movement toward 134greater order, complexity and interrelatedness. The person-centered approach is built on trust that individuals and groups can set their own goals and monitor their own progress towards them. It assumes that the clients can be trusted to select their own therapist, choose the frequency and length of their therapy, talk or be silent, decide what needs to be explored, achieve their own insights, and be the architects of own lives. Moreover, groups can be trusted to develop processes right for them and to resolve conflicts in the group. In Person-Centered Therapy, the therapist provides continuous and constant empathy for the client's perceptions, meanings and feelings. -

The Concept of Organism, a Historical and Conceptual Critique

Do organisms have an ontological status? Charles T. Wolfe Unit for History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney [email protected] forthcoming in History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 32:2-3 (2010) Abstract The category of „organism‟ has an ambiguous status: is it scientific or is it philosophical? Or, if one looks at it from within the relatively recent field or sub-field of philosophy of biology, is it a central, or at least legitimate category therein, or should it be dispensed with? In any case, it has long served as a kind of scientific “bolstering” for a philosophical train of argument which seeks to refute the “mechanistic” or “reductionist” trend, which has been perceived as dominant since the 17th century, whether in the case of Stahlian animism, Leibnizian monadology, the neo-vitalism of Hans Driesch, or, lastly, of the “phenomenology of organic life” in the 20th century, with authors such as Kurt Goldstein, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Georges Canguilhem. In this paper I try to reconstruct some of the main interpretive „stages‟ or „layers‟ of the concept of organism in order to critically evaluate it. How might „organism‟ be a useful concept if one rules out the excesses of „organismic‟ biology and metaphysics? Varieties of instrumentalism and what I call the „projective‟ concept of organism are appealing, but perhaps ultimately unsatisfying. 1. What is an organism? There have been a variety of answers to this question, not just in the sense of different definitions (an organism is a biological individual; it is a living being, or at least the difference between a living organism and a dead organism is somehow significant in a way that does not seem to make sense for other sorts of entities, like lamps and chairs; it is a self-organizing, metabolic system; etc.) but more tendentiously, in the 1 sense that philosophers, scientists, „natural philosophers‟ and others have both asserted and denied the existence of organisms. -

Nondirective Counseling

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 140 Nondirective Counseling Effects of Short Training and Individual Characteristics of Clients BY ERIK RAUTALINKO ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2004 ! "#$ % & % % ' ( ) * *( + , -( !( . &( -%% % ) & / . % . ( 0 ( ! ( 12 ( ( /3 45$$!51 "15! & * & 6 % ( / % % . + & 7 & % % & & ( ) * %* * % & & ( ) % %% % & & 8 * %% % ( ) 7 5 9' /5///: ( / ' / * +% & 9+;< , % &: , % % & & ( ) & +; , * % &( ) * * %% ( / ' // & * % % +; & % & ( 0 & , 7 % * & & % =& % =& * ( / ' /// * & 7 +; 5 7 * =& * %% , & ( +; & * 5 7 =&6 & * , & ( / & %% , & 8 % % , % & , & ( & % & 5 7 & , & ! " #! $% &''(! ! )*(&+' ! > -, + , ! / 25?!4 /3 45$$!51 "15! # ### 5!$$ 9 #@@ (,(@ A B # ### 5!$$: LIST OF PAPERS Paper I: Rautalinko, E., & Lisper, H.-O. (2004). Effects of training reflective listening in a corporate setting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 281-299. Paper II: Rautalinko, E., Lisper, H.-O., & Ekehammar, B. (2004). Training reflective listening -

Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship

Éisteach Volume 14 l Issue 2 l Summer 2014 Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship by Ian Woods Abstract This article gives a brief biographical sketch of Carl Rogers (1902-1987) and Martin Buber (1878-1965) and summarises their respective views on relationship before outlining the public dialogue in which they engaged in 1957. The outline concentrates on the part of the dialogue dealing with the therapist-client relationship and indicates some of the essential points of the exchanges between the two men, drawing out their differing perspectives. As well as commenting also on Brian Thorne’s view of the dialogue, the author’s own views are indicated both on the content of the dialogue and its implications for practice. The two men. assumption of power in 1933. He 1937 was published in English as “I arl Rogers and Martin Buber met had by then become the leading and Thou”. Cin public dialogue on 18 April interpreter of Hasidism and Jewish Following an enforced departure 1957 in the University of Michigan, mysticism and had begun what from Germany in 1938 (the same U.S.A. There was an age difference became a lifetime’s large literary year as Freud’s move to England), of 24 years between them, Buber output including more than sixty Buber became professor at the being 79 and Rogers 55 at the volumes on religious, philosophical Hebrew University of Jerusalem until time. The difference in background and related subjects. In 1923 he his retirement in 1951. During the between the two men was even more published “Ich und Du” which in early years of the State of Israel, he considerable. -

Winds of Change for Client-Centered Counseling

WINDS OF CHANGE FOR CLIENT-CENTERED COUNSELING C. H. PATTERSON Humanistic Education and Development, 1993, 31, 130-133. In Understanding Psychotherapy: Fifty Years of Client-Centered Theory and Practice. PCCS Books, 2000. The winds of change they are ablowing. Client-centered counseling should be growing. The winds of change are blowing on client-centered counseling (among others, Cain, 1986, 1989a, 1989b, 1989c, 1990; Combs, 1988; Sachse, 1989; Sebastian, 1989). In the 3 years following the death of Carl Rogers, many were expressing dissatisfaction with ''traditional'' or "pure'' client-centered counseling and were engaged in trying to supplement it, extend it, and modify it. The basic complaint seems to be that the counselor conditions specified by Rogers (1957) are not sufficient. Tausch, at the International Conference on Client-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapy in Belgium in 1988, is quoted by Cain (1989c) as stating that client-centered therapy, in its pure form, is not effective for some clients and insufficient for others. Cain (1989c) commented on Gendlin's (1988) plenary address at the Belgium conference, noting that "some consider Gendlin's work a creative extension of client-centered therapy, while others contend that experiential therapy is simply incompatible with the theory and practice of client-centered therapy" (pp. 5-6). Brodley (1988) belongs to the latter group, judging from her paper at the same conference "Client-Centered and Experiential-Two Different Therapies.'' Cain (1989c) reported that Gendlin said he -

Personal Construct Psychology

WHAT WE EXPECT WHAT WE GET WHAT WE GET How did we get to this…and how do we recover? NEW AND IMPROVED THEORY? OR….. SAME OLE’ THING…WITH A NEW LOOK. Ecclesiastes 1:9 Structure of Sanctuary “Given the evidence that treatments are about equally effective, that treatments WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT delivered in clinical settings are PSYCHOTHERAPY? AND WHAT IS THERE LEFT TO DEBATE? effective (and as effective as that BRUCE E. WAMPOLD, PH.D., provided in clinical trials), that ABPPZAC E. IMEL, PH.D. 2018 the manner in which treatments are provided are much more important than which treatment is provided, mandating particular treatments seems illogical.” “THE DEVELOPMENT OF A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP IS THE MOST ACCURATE INDICATOR OF A POSITIVE OUTCOME.” - J. ERIC GENTRY CARL ROGERS • January 1902-February 1987 • Person Centered Therapy • Unconditional Positive Regard + Congruence = Person Centered Treatment “I am not perfect…but I am enough.” PAUL D. MACLEAN • May 1913-December 2007 • Triune Brain • Three Distinct Brain Segments: Protoreptilian Paleomammalian Neomammalian “An interest in the brain requires no justification other than a curiosity to know why we are here, what we are doing here, and where we are going.” THE TRIUNE BRAIN Reptilian Brain Limbic Brain Neocortex ERIK ERIKSON • June 1902-May 1994 • Stages of Development • Development happens in stages with spectrum type “virutes” “Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive.” STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT • Traumatic Reenactment regresses an -

Introducing Person-Centred Counselling 1 Introducing Person-Centred 1 Counselling

Introducing person-centred counselling 1 Introducing person-centred 1 counselling This book is about the Person-Centred Approach (PCA) to counselling. It is for counsellors, therapists, and clinical psychologists either practising or in training, and for people who use counselling skills as part of their work, but who do not want to be full-time counsellors — nurses, teachers, social workers, personnel managers, and community workers, for example. It is based on the work of Carl Rogers (1902–1987), one of the leading counselling psychologists of the twentieth century, who was responsible for some of the most original research work ever undertaken into the factors that facilitate personal and social change (see, for example, Rogers, 1957a, 1959). Throughout a career that spanned more than fifty years as a writer, researcher, and practitioner, Rogers developed and refined an approach to counselling that is widely recognised as one of the most creative and effective ways of helping people in need. Although this book is focused on person-centred counselling, I see it as useful for people exploring a range of different approaches before committing themselves to one in particular, and a valuable resource for counselling trainers, whether person-centred or not. It offers ideas and perspectives, perhaps even inspiration occasionally, and makes reference to some of the literature, both classical and recent. I have tried to be careful about giving the sources for the material in this book, and I am indebted to the many authors I have referred to in writing it. The hundreds, perhaps thousands of hours spent discussing the person-centred approach to counselling with students and others, talking with practitioners and being with clients, have contributed to the content of this book. -

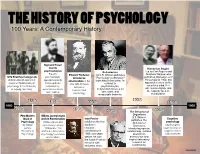

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

The Balance of Personality

The Balance of Personality The Balance of Personality CHRIS ALLEN PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY The Balance of Personality by Chris Allen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The Balance of Personality Copyright © by Chris Allen is licensed under an Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, except where otherwise noted. Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements x Front Cover Photo: x Special Thanks to: x Open Educational Resources xi Introduction 1 1. Personality Traits 3 Introduction 3 Facets of Traits (Subtraits) 7 Other Traits Beyond the Five-Factor Model 8 The Person-Situation Debate and Alternatives to the Trait Perspective 10 2. Personality Stability 17 Introduction 18 Defining Different Kinds of Personality Stability 19 The How and Why of Personality Stability and Change: Different Kinds of Interplay Between Individuals 22 and Their Environments Conclusion 25 3. Personality Assessment 30 Introduction 30 Objective Tests 31 Basic Types of Objective Tests 32 Other Ways of Classifying Objective Tests 35 Projective and Implicit Tests 36 Behavioral and Performance Measures 38 Conclusion 39 Vocabulary 39 4. Sigmund Freud, Karen Horney, Nancy Chodorow: Viewpoints on Psychodynamic Theory 43 Introduction 43 Core Assumptions of the Psychodynamic Perspective 45 The Evolution of Psychodynamic Theory 46 Nancy Chodorow’s Psychoanalytic Feminism and the Role of Mothering 55 Quiz 60 5. Carl Jung 63 Carl Jung: Analytic Psychology 63 6. Humanistic and Existential Theory: Frankl, Rogers, and Maslow 78 HUMANISTIC AND EXISTENTIAL THEORY: VIKTOR FRANKL, CARL ROGERS, AND ABRAHAM 78 MASLOW Carl Rogers, Humanistic Psychotherapy 85 Vocabulary and Concepts 94 7. -

The Human Being: J.L. Moreno's Vision in Psychodrama

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY, VOL. 8, NO. 1, MARCH 2003, pp. 31 – 36 The human being: J.L. Moreno’s vision in psychodrama NORBERT APTER Institut ODeF, 65, rue de Lausanne, CH – 1202, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract Integrating two different psychotherapeutic approaches is more and more frequent among psychologists. Psychodrama is often chosen as one. In order to be coherent and efficient, serious attention must be paid to verifying the compatibility of the two chosen approaches when integrating them (even partly), especially in terms of their vision of the human being. In order to facilitate this necessary verification, Norbert Apter reviews here Moreno’s psychodrama vision of the human being: a relational being, the spontaneity and creativity of which form the pillars enabling him to actualize his interactions and the interiorized roles on which he relies. Introduction Many psychologists throughout the world rely on psychodrama and its tools. There are many non-psychodramatists who have chosen to integrate only certain aspects of the method into their own school of psychotherapy (psychoanalysis, Jungian analysis, Adlerian analysis, family therapy, cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy, etc . .). (Blatner & Blatner, 1988, p. 2) list some 13 major therapeutic currents in which professionals chose to include some elements of psychodrama as a tool. The technique of psychodrama according to a given vision of the human being1 was developed by the psychiatrist, Jacob Levy Moreno (1889 – 1974). However, visions of the human being underlying various implementations of psychodrama are diverse and varied. Many people use psychodrama based on an approach that differs from Moreno’s vision of the human being. -

The Organismic Psychology of Andras Angyal in Relation to Sri Aurobindo’S Philosophy of Integral Nondualism

The Organismic Psychology of Andras Angyal in Relation to Sri Aurobindo’s Philosophy of Integral Nondualism The Organismic Psychology of Andras Angyal in Relation to Sri Aurobindo’s Philosophy of Integral Nondualism RICHARD P. MARSH (Published in “The Integral Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo – A Commemorative Symposium Edited by Haridas Chaudhuri and Frederic Spiegelberg” by GEORGE ALLEN &UNWIN LTD.) - 1 - The Organismic Psychology of Andras Angyal in Relation to Sri Aurobindo’s Philosophy of Integral Nondualism COMPARATIVE studies of Eastern and Western psychological and religious concepts often make references to the works of Dr C. G. Jung, the founder of analytical psychology. This is altogether proper. Dr Jung, as is well known, has undertaken various forms of psychological research with an inevitable appeal to students of Asian thought. He has, in addition, communicated the results of his research with a sensitivity and a resourcefulness which have added to their appeal. Similarly, the achievement of Sri Aurobindo in creating the philosophy of integral nondualism, a remarkable blend of original thought with much that is first rate and enduring in both the Eastern and the Western traditions, has led to cross comparisons from the other side. In reading Aurobindo, one constantly experiences the shock of recognition. It is as though in Aurobindo one had rediscovered the West, or as if one had come across a new Dr Jung with a startling new vocabulary and a curiously vivid and massive style. So much of Jung is there, although cut to the pattern of a different idiom: the phenomenon of introversion, the concept of the collective unconscious, the relationship of ego to self, even in a sense the classification into psychological types-these and more are in Aurobindo, inviting comparison. -

Xerox University Microfilms -300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 77-2344

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.