The Human Being: J.L. Moreno's Vision in Psychodrama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Person-Centred Therapy Vs. Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy

PERSON-CENTRED THERAPY VS. RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY The purpose of this paper is to present a brief comparison of the approach to psychotherapy of Carl Rogers and Albert Ellis. I have selected Albert Ellis for comparative purposes since he was one of the other therapists participating with Rogers in the film “Three Approaches to Psycotherapy” , made in 1964, centering on interviews with the client “Gloria”. Person-Centered Therapy Rogers first formulated the essentials of Person-Centered Therapy (PCT), an approach to helping individuals and groups in conflict, in 1940. At the time it was a revolutionary hypothesis that a self-directed growth process would follow the provision and reception of a particular kind of relationship characterized by genuineness, non-judgmental caring, and empathy. Its most fundamental and pervasive concept is trust. The foundation of Rogers’ approach is a human being’s actualizing tendency towards the realization of his or her full potential; which he described as a formative tendency observable in the movement toward 134greater order, complexity and interrelatedness. The person-centered approach is built on trust that individuals and groups can set their own goals and monitor their own progress towards them. It assumes that the clients can be trusted to select their own therapist, choose the frequency and length of their therapy, talk or be silent, decide what needs to be explored, achieve their own insights, and be the architects of own lives. Moreover, groups can be trusted to develop processes right for them and to resolve conflicts in the group. In Person-Centered Therapy, the therapist provides continuous and constant empathy for the client's perceptions, meanings and feelings. -

Nondirective Counseling

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 140 Nondirective Counseling Effects of Short Training and Individual Characteristics of Clients BY ERIK RAUTALINKO ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2004 ! "#$ % & % % ' ( ) * *( + , -( !( . &( -%% % ) & / . % . ( 0 ( ! ( 12 ( ( /3 45$$!51 "15! & * & 6 % ( / % % . + & 7 & % % & & ( ) * %* * % & & ( ) % %% % & & 8 * %% % ( ) 7 5 9' /5///: ( / ' / * +% & 9+;< , % &: , % % & & ( ) & +; , * % &( ) * * %% ( / ' // & * % % +; & % & ( 0 & , 7 % * & & % =& % =& * ( / ' /// * & 7 +; 5 7 * =& * %% , & ( +; & * 5 7 =&6 & * , & ( / & %% , & 8 % % , % & , & ( & % & 5 7 & , & ! " #! $% &''(! ! )*(&+' ! > -, + , ! / 25?!4 /3 45$$!51 "15! # ### 5!$$ 9 #@@ (,(@ A B # ### 5!$$: LIST OF PAPERS Paper I: Rautalinko, E., & Lisper, H.-O. (2004). Effects of training reflective listening in a corporate setting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 281-299. Paper II: Rautalinko, E., Lisper, H.-O., & Ekehammar, B. (2004). Training reflective listening -

Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship

Éisteach Volume 14 l Issue 2 l Summer 2014 Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship by Ian Woods Abstract This article gives a brief biographical sketch of Carl Rogers (1902-1987) and Martin Buber (1878-1965) and summarises their respective views on relationship before outlining the public dialogue in which they engaged in 1957. The outline concentrates on the part of the dialogue dealing with the therapist-client relationship and indicates some of the essential points of the exchanges between the two men, drawing out their differing perspectives. As well as commenting also on Brian Thorne’s view of the dialogue, the author’s own views are indicated both on the content of the dialogue and its implications for practice. The two men. assumption of power in 1933. He 1937 was published in English as “I arl Rogers and Martin Buber met had by then become the leading and Thou”. Cin public dialogue on 18 April interpreter of Hasidism and Jewish Following an enforced departure 1957 in the University of Michigan, mysticism and had begun what from Germany in 1938 (the same U.S.A. There was an age difference became a lifetime’s large literary year as Freud’s move to England), of 24 years between them, Buber output including more than sixty Buber became professor at the being 79 and Rogers 55 at the volumes on religious, philosophical Hebrew University of Jerusalem until time. The difference in background and related subjects. In 1923 he his retirement in 1951. During the between the two men was even more published “Ich und Du” which in early years of the State of Israel, he considerable. -

Winds of Change for Client-Centered Counseling

WINDS OF CHANGE FOR CLIENT-CENTERED COUNSELING C. H. PATTERSON Humanistic Education and Development, 1993, 31, 130-133. In Understanding Psychotherapy: Fifty Years of Client-Centered Theory and Practice. PCCS Books, 2000. The winds of change they are ablowing. Client-centered counseling should be growing. The winds of change are blowing on client-centered counseling (among others, Cain, 1986, 1989a, 1989b, 1989c, 1990; Combs, 1988; Sachse, 1989; Sebastian, 1989). In the 3 years following the death of Carl Rogers, many were expressing dissatisfaction with ''traditional'' or "pure'' client-centered counseling and were engaged in trying to supplement it, extend it, and modify it. The basic complaint seems to be that the counselor conditions specified by Rogers (1957) are not sufficient. Tausch, at the International Conference on Client-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapy in Belgium in 1988, is quoted by Cain (1989c) as stating that client-centered therapy, in its pure form, is not effective for some clients and insufficient for others. Cain (1989c) commented on Gendlin's (1988) plenary address at the Belgium conference, noting that "some consider Gendlin's work a creative extension of client-centered therapy, while others contend that experiential therapy is simply incompatible with the theory and practice of client-centered therapy" (pp. 5-6). Brodley (1988) belongs to the latter group, judging from her paper at the same conference "Client-Centered and Experiential-Two Different Therapies.'' Cain (1989c) reported that Gendlin said he -

Personal Construct Psychology

WHAT WE EXPECT WHAT WE GET WHAT WE GET How did we get to this…and how do we recover? NEW AND IMPROVED THEORY? OR….. SAME OLE’ THING…WITH A NEW LOOK. Ecclesiastes 1:9 Structure of Sanctuary “Given the evidence that treatments are about equally effective, that treatments WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT delivered in clinical settings are PSYCHOTHERAPY? AND WHAT IS THERE LEFT TO DEBATE? effective (and as effective as that BRUCE E. WAMPOLD, PH.D., provided in clinical trials), that ABPPZAC E. IMEL, PH.D. 2018 the manner in which treatments are provided are much more important than which treatment is provided, mandating particular treatments seems illogical.” “THE DEVELOPMENT OF A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP IS THE MOST ACCURATE INDICATOR OF A POSITIVE OUTCOME.” - J. ERIC GENTRY CARL ROGERS • January 1902-February 1987 • Person Centered Therapy • Unconditional Positive Regard + Congruence = Person Centered Treatment “I am not perfect…but I am enough.” PAUL D. MACLEAN • May 1913-December 2007 • Triune Brain • Three Distinct Brain Segments: Protoreptilian Paleomammalian Neomammalian “An interest in the brain requires no justification other than a curiosity to know why we are here, what we are doing here, and where we are going.” THE TRIUNE BRAIN Reptilian Brain Limbic Brain Neocortex ERIK ERIKSON • June 1902-May 1994 • Stages of Development • Development happens in stages with spectrum type “virutes” “Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive.” STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT • Traumatic Reenactment regresses an -

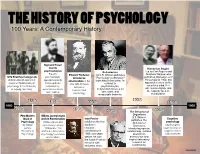

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

Healthy Personality

HEALTHY PERSONALITY Presented by CONTINUING PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATION 7.2 CONTACT HOURS “I wanted to prove that human beings are capable of something grander than war and prejudice and hatred.” Abraham Maslow, Psychology Today, 1968, 2, p.55. Course Objective Learning Objectives The purpose of this course is to provide an Upon completion, the participant will understand understanding of the concept of healthy personality. the nature, motivation, and characteristics of the Seven theorists offer their views on the subject, healthy personality. Seven influential including: Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, Erich psychotherapists-theorists examine the concept Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung, Viktor of healthy personality allowing the reader to Frankl, and Fritz Perls. integrate these principles into his or her own life. Accreditation Faculty Provider approved by the California Board of Neil Eddington, Ph.D. Registered Nursing, Provider # CEP 14008, for Richard Shuman, MFT 7.2 Contact Hours. In accordance with the California Code of Regulations, Section 2540.2(b) for licensed vocational nurses and 2592.2(b) for psychiatric technicians, this course is accepted by the Board of Vocational Nursing and Psychiatric Technicians for 7.2 contact hours of continuing education credit. Mission Statement Continuing Psychology Education provides the highest quality continuing education designed to fulfill the professional needs and interests of nurses. Resources are offered to improve professional competency, maintain knowledge of the latest advancements, and meet continuing education requirements mandated by the profession. Copyright © 2006 Continuing Psychology Education 1 Continuing Psychology Education P.O. Box 9659 San Diego, CA 92169 FAX: (858) 272-5809 phone: 1 800 281-5068 www.texcpe.com HEALTHY PERSONALITY INTRODUCTION personality offered by Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, Erich Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung, Viktor Frankl, and Fritz The study of healthy personality was ignored for a long time Perls. -

Major Schools of Thought in Psychology

Major Schools of Thought in Psychology When psychology was first established as a science separate from biology and philosophy, the debate over how to describe and explain the human mind and behavior began. The first school of thought, structuralism, was advocated by the founder of the first psychology lab, Wilhelm Wundt . Almost immediately, other theories began to emerge and vie for dominance in psychology. The following are some of the major schools of thought that have influenced our knowledge and understanding of psychology: Structuralism vs. Functionalism: Structuralism was the first school of psychology, and focused on breaking down mental processes into the most basic components. Major structuralist thinkers include Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener. Functionalism formed as a reaction to the theories of the structuralist school of thought and was heavily influenced by the work of William James . Major functionalist thinkers included John Dewey and Harvey Carr. Behaviorism: Behaviorism became the dominant school of thought during the 1950s. Based upon the work of thinkers such as John B. Watson , Ivan Pavlov , and B. F. Skinner , behaviorism holds that all behavior can be explained by environmental causes, rather than by internal forces. Behaviorism is focused on observable behavior . Theories of learning including classical conditioning and operant conditioning were the focus of a great deal of research. Psychoanalysis : Sigmund Freud was the found of psychodynamic approach. This school of thought emphasizes the influence of the unconscious mind on behavior. Freud believed that the human mind was composed of three elements: the id , the ego , and the superego. Other major psychodynamic thinkers include Anna Freud, Carl Jung, and Erik Erikson. -

Carl R. Rogers Collection, 1902-1990

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n977 No online items Guide to the Carl R. Rogers Collection, 1902-1990 Project archivist: David C. Gartrell; student assistants: Krnee Deemark, Joyce Jiang, Mike Steiner; machine-readable finding aid created by David C. Gartrell Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Carl R. Rogers HPA Mss 32 1 Collection, 1902-1990 Guide to the Carl R. Rogers Collection, 1902-1990 Collection number: HPA Mss 32 Department of Special Collections Donald C. Davidson Library Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Contact Information: Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html Project Archivist: David C. Gartrell Student Assistants: Krnee Deemark, Joyce Jiang, Mike Steiner Date Completed: Last revised: 20 December 1999 Encoded by: David C. Gartrell © 1999 the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Carl R. Rogers Collection, Date (inclusive): 1902-1990 Collection number: HPA Mss 32 Creator: Rogers, Carl R. Center for the Studies of the Person Forms part of: The Humanistic Psychology Archives Extent: 52 manuscript boxes, two oversize boxes, approximately 350 audiovisual items; approximately 35 linear feet Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara. -

An Existential Criterion of Normal and Abnormal Personality in the Works of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers Sergey A

Psychology in Russia: State of the Art Russian Lomonosov Psychological Moscow State Volume 9, Issue 2, 2016 Society University Personality psychology An existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality in the works of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers Sergey A. Kapustin Psychology Faculty, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] This article is the third in a series of four articles scheduled for publication in this jour- nal. In the first article (Kapustin, 2015a) I proposed a description of a new so-called ex- istential criterion of normal and abnormal personality that is implicitly present in the works of Erich Fromm. According to this criterion, normal and abnormal personalities are determined, first, by special features of the content of their position regarding exis- tential dichotomies that are natural to human beings and, second, by particular aspects of the formation of this position. Such dichotomies, entitatively existent in all human life, are inherent, two-alternative contradictions. The position of a normal personality in its content orients a person toward a contradictious predetermination of life in the form of existential dichotomies and necessitates a search for compromise in resolving these dichotomies. This position is created on a rational basis with the person’s ac- tive participation. The position of an abnormal personality in its content subjectively denies a contradictious predetermination of life in the form of existential dichotomies and orients a person toward a consistent, noncompetitive, and, as a consequence, one- sided way of life that doesn’t include self-determination. This position is imposed by other people on an irrational basis. -

Rediscovering Rogers's Self Theory and Personality

Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology Nik Ahmad, Mustafa Tekke Vol. 4, No. 3, 2015 Rediscovering Rogers’s Self Theory and Personality Nik Ahmad Hisham Ismail Institute of Education, International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) Phone No: +603 6196 4000 [email protected] Mustafa Tekke (Corresponding author) Turkey Institute of Education, International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) Phone No: +60188730772 [email protected] Abstract This study examined the self theory of Carl Rogers in depth. There are some important concepts illuminated well, considering one’s personality development. Its main focus was positive regard, self-worth and actualizing tendency, proposed by Rogers. To explain them in brief, positive regard was studied through self-image, ideal self and congruence. Self- worth is described as conditional and unconditional to cope with challenges in life, tolerate failures and sadness at times. Actualizing tendency was expounded into fully functioning or self-actualizing. These all concepts indicated that having a tendency on human behavior and concentrating on the capacity of individuals to think intentionally and soundly, to control their biological urges, are significantly main elements to evaluate one’s self. Therefore, in the humanistic perspective, individuals have the opportunity and will to change their states of mind and behavior. This study might be a guide to some certain aspect of self related studies for other researchers to benefit accordingly and also to develop a new scale related to self using Rogers’s theory. Keywords: Rogers, personality, self, positive regard, actualizing tendency Introduction developed on actualizing tendency (Schultz & Schultz, 2013). The paper presents the theory of Carl Roger`s self. -

Major Philosophical Implications of Carl Rogers' Theory of Personality

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1964 Major Philosophical Implications of Carl Rogers' Theory of Personality Daniel Artley Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Artley, Daniel, "Major Philosophical Implications of Carl Rogers' Theory of Personality" (1964). Master's Theses. 1869. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 1964 Daniel Artley MAJOR PHILOSOPHICAL IMPLICATIONS 0' OARL ROGERS· THEORY OF PERSONALITY b7 Daniel w. Artle,.. S.J. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts 1n Ph11osopbT septJember 1964 CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ., . • • 1 A. Justitication tor and Purpose of This Thesis •• 1 1. Justifioation • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 1 a) Rogers has tormulated a theory ot per sonality that is the subject ot much attention todq. ............". 1 b) He recognizes the need tor a psycholo- glst to have a proper philosophy. • • • •• 1 (1) ae has explicitly tried to tormu- late the basic philosophioal toun- dation of his theory ot personality_ • 1 (2) He believes philosophy is important for all psyohologists. ••• _ • • •• 2 2. Purpose is to present the major philosoph ioal implications that underlie Rogers' theor,y ot personality and the major oriti oism to whioh this philosophy has been subjected. " • • • • • " • • • • • • • • • • _ B.