What Did Carl Rogers Say on the Topic of Therapist Self-Disclosure? a Comprehensive Review of His Recorded Clinical Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty in Counseling Psychology & Community Services Tamba-Kuii

Faculty in Counseling Psychology & Community Services Tamba-Kuii Bailey, Ph.D. (Georgia State University), Assistant Professor. Co-Coordinator of the on-campus Master’s Program. Training: Ethics and laws; clinical supervision; diagnosis, psychopathology and treatment; and counseling methods. Research: Internalized racial oppression; racial oppression and mental health functioning; Black psychology; and multicultural psychology. Clinical: Interpersonal theory; psychodynamic therapy; multicultural and feminist counseling; and person- centered therapy. Email: [email protected]. Currently accepting Ph.D. and MA students. Emily Brinck, Ph.D. (University of Wisconsin, Madison), Director & Assistant Professor of Rehabilitation and Human Services. Training: Foundations of Rehabilitation Counseling, Assessments; counseling theories and techniques; career development; multicultural issues; medical and psychosocial aspects of disabilities. Research: Interagency Collaboration between schools, vocational rehabilitation, and businesses; WIOA; Transition age youth with disabilities; Vocational Rehabilitation; Supervision; psychiatric disabilities. Clinical: Mental Health counseling in the criminal justice system; client-centered approaches for to help individuals with disabilities obtain psychological, social, and vocational functioning. Email: [email protected]. Currently accepting MA students and may accept Ph.D. students. Klaus E. Cavalhieri, Ph.D. (Southern Illinois University, Carbondale), Assistant Professor. Training: Multicultural -

M.A. in Counseling Psychology with Emphasis in Marriage and Family Therapy, Professional Clinical Counseling, and Depth Psychology

M.A. IN COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY WITH EMPHASIS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY THERAPY, PROFESSIONAL CLINICAL COUNSELING, AND DEPTH PSYCHOLOGY PACIFICA GRADUATE INSTITUTE | 249 LAMBERT ROAD, CARPINTERIA, CALIFORNIA 93013 | PACIFICA.EDU M.A. IN COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY WITH EMPHASIS IN MARRIAGE AND FAMILY THERAPY, PROFESSIONAL CLINICAL COUNSELING, AND DEPTH PSYCHOLOGY The M.A. Counseling Psychology Program with Emphasis in Marriage and Family Therapy, Professional Clinical Counseling, and Depth Psychology is dedicated to offering students unique and evidence-based comprehensive training in the art of marriage, family, and individual psychotherapy and professional clinical counseling with an appreciation for the systemic and immeasurable dimensions of the psyche. Depth psychology invites a curiosity about the psyche and respect for the diversity and resiliency of the human experience. Transdisciplinary courses in literature, mythology, religion, and culture deepen students’ abilities to link collective systems and archetypal themes to sociopolitical issues in the lives of individuals, families, and communities. As preparation for professional licensure in Marriage and Family Therapy (LMFT) and Professional Clinical Counseling (LPCC), a rigorous two-and-a-half year academic program emphasizes theoretical understanding and experiential training in clinical skills, inclusive of a supervised practicum traineeship experience. Research studies and thesis writing prepare students to explore and contribute to the tradition of scholarship within the depth psychological tradition to further Pacifica’s dedication to thoughtful and soulful practice. At its core, the Counseling Psychology Program honors the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists distinctive call to the service 2018 Outstanding School of the individual and collective or Agency Award psyche. presented to MATTHEW BENNETT, Founded on a deep relational PSY.D. -

Clinical Versus Counseling Psychology: What's the Diff? by John C

Clinical Versus Counseling Psychology: What's the Diff? by John C. Norcross - University of Scranton, Fields of Psychology Graduate School The majority of psychology students applying to graduate school are interested in clinical work, and approximately half of all graduate degrees in psychology are awarded in the subfields of clinical and counseling psychology (Mayne, Norcross, & Sayette, 2000). But deciding on a health care specialization in psychology gets complicated. The urgent question facing each student--and the question frequently posed to academic advisors--is "What are the differences between clinical psychology and counseling psychology?" Or, as I am asked in graduate school workshops, "What's the diff?" This article seeks to summarize the considerable similarities and salient differences between these two psychology subfields on the basis of several recent research studies. The results can facilitate your informed choice in the application process, enhance matching between the specialization and your interests, and sharpen the respective identities of psychology training programs. Considerable Similarities The distinctions between clinical psychology and counseling psychology have steadily faded in recent years, leading many to recommend a merger of the two. Graduates of doctoral- level clinical and counseling psychology programs are generally eligible for the same professional benefits, such as psychology licensure, independent practice, and insurance reimbursement. The American Psychological Association (APA) ceased distinguishing -

Person-Centred Therapy Vs. Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy

PERSON-CENTRED THERAPY VS. RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY The purpose of this paper is to present a brief comparison of the approach to psychotherapy of Carl Rogers and Albert Ellis. I have selected Albert Ellis for comparative purposes since he was one of the other therapists participating with Rogers in the film “Three Approaches to Psycotherapy” , made in 1964, centering on interviews with the client “Gloria”. Person-Centered Therapy Rogers first formulated the essentials of Person-Centered Therapy (PCT), an approach to helping individuals and groups in conflict, in 1940. At the time it was a revolutionary hypothesis that a self-directed growth process would follow the provision and reception of a particular kind of relationship characterized by genuineness, non-judgmental caring, and empathy. Its most fundamental and pervasive concept is trust. The foundation of Rogers’ approach is a human being’s actualizing tendency towards the realization of his or her full potential; which he described as a formative tendency observable in the movement toward 134greater order, complexity and interrelatedness. The person-centered approach is built on trust that individuals and groups can set their own goals and monitor their own progress towards them. It assumes that the clients can be trusted to select their own therapist, choose the frequency and length of their therapy, talk or be silent, decide what needs to be explored, achieve their own insights, and be the architects of own lives. Moreover, groups can be trusted to develop processes right for them and to resolve conflicts in the group. In Person-Centered Therapy, the therapist provides continuous and constant empathy for the client's perceptions, meanings and feelings. -

Nondirective Counseling

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 140 Nondirective Counseling Effects of Short Training and Individual Characteristics of Clients BY ERIK RAUTALINKO ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2004 ! "#$ % & % % ' ( ) * *( + , -( !( . &( -%% % ) & / . % . ( 0 ( ! ( 12 ( ( /3 45$$!51 "15! & * & 6 % ( / % % . + & 7 & % % & & ( ) * %* * % & & ( ) % %% % & & 8 * %% % ( ) 7 5 9' /5///: ( / ' / * +% & 9+;< , % &: , % % & & ( ) & +; , * % &( ) * * %% ( / ' // & * % % +; & % & ( 0 & , 7 % * & & % =& % =& * ( / ' /// * & 7 +; 5 7 * =& * %% , & ( +; & * 5 7 =&6 & * , & ( / & %% , & 8 % % , % & , & ( & % & 5 7 & , & ! " #! $% &''(! ! )*(&+' ! > -, + , ! / 25?!4 /3 45$$!51 "15! # ### 5!$$ 9 #@@ (,(@ A B # ### 5!$$: LIST OF PAPERS Paper I: Rautalinko, E., & Lisper, H.-O. (2004). Effects of training reflective listening in a corporate setting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 281-299. Paper II: Rautalinko, E., Lisper, H.-O., & Ekehammar, B. (2004). Training reflective listening -

Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship

Éisteach Volume 14 l Issue 2 l Summer 2014 Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship by Ian Woods Abstract This article gives a brief biographical sketch of Carl Rogers (1902-1987) and Martin Buber (1878-1965) and summarises their respective views on relationship before outlining the public dialogue in which they engaged in 1957. The outline concentrates on the part of the dialogue dealing with the therapist-client relationship and indicates some of the essential points of the exchanges between the two men, drawing out their differing perspectives. As well as commenting also on Brian Thorne’s view of the dialogue, the author’s own views are indicated both on the content of the dialogue and its implications for practice. The two men. assumption of power in 1933. He 1937 was published in English as “I arl Rogers and Martin Buber met had by then become the leading and Thou”. Cin public dialogue on 18 April interpreter of Hasidism and Jewish Following an enforced departure 1957 in the University of Michigan, mysticism and had begun what from Germany in 1938 (the same U.S.A. There was an age difference became a lifetime’s large literary year as Freud’s move to England), of 24 years between them, Buber output including more than sixty Buber became professor at the being 79 and Rogers 55 at the volumes on religious, philosophical Hebrew University of Jerusalem until time. The difference in background and related subjects. In 1923 he his retirement in 1951. During the between the two men was even more published “Ich und Du” which in early years of the State of Israel, he considerable. -

Winds of Change for Client-Centered Counseling

WINDS OF CHANGE FOR CLIENT-CENTERED COUNSELING C. H. PATTERSON Humanistic Education and Development, 1993, 31, 130-133. In Understanding Psychotherapy: Fifty Years of Client-Centered Theory and Practice. PCCS Books, 2000. The winds of change they are ablowing. Client-centered counseling should be growing. The winds of change are blowing on client-centered counseling (among others, Cain, 1986, 1989a, 1989b, 1989c, 1990; Combs, 1988; Sachse, 1989; Sebastian, 1989). In the 3 years following the death of Carl Rogers, many were expressing dissatisfaction with ''traditional'' or "pure'' client-centered counseling and were engaged in trying to supplement it, extend it, and modify it. The basic complaint seems to be that the counselor conditions specified by Rogers (1957) are not sufficient. Tausch, at the International Conference on Client-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapy in Belgium in 1988, is quoted by Cain (1989c) as stating that client-centered therapy, in its pure form, is not effective for some clients and insufficient for others. Cain (1989c) commented on Gendlin's (1988) plenary address at the Belgium conference, noting that "some consider Gendlin's work a creative extension of client-centered therapy, while others contend that experiential therapy is simply incompatible with the theory and practice of client-centered therapy" (pp. 5-6). Brodley (1988) belongs to the latter group, judging from her paper at the same conference "Client-Centered and Experiential-Two Different Therapies.'' Cain (1989c) reported that Gendlin said he -

1 Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral Interventions to Positively Impact

1 Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral Interventions to Positively Impact Academic Achievement in Middle School Students Brett Zyromski Southern Illinois University Carbondale Arline Edwards Joseph North Carolina State University Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral 2 Abstract Empirical research suggests a correlation between Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) interventions and increased academic achievement of students in middle schools. An argument was presented for utilizing CBT intervention within the delivery system of comprehensive school counseling programs in middle schools; specifically in individual counseling, small group counseling, and classroom guidance lessons. Practical examples and resources were provided to assist school counselors in implementing CBT interventions to help students control cognitive thought processes and positively impact academic achievement. Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral 3 Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral Interventions to Positively Impact Academic Achievement in Middle School Students A professional school counselors’ role is to remove barriers to students’ success; enhancing students’ learning environments and supporting students’ academic achievement (American School Counseling Association, 2005). The American School Counseling Association (ASCA) (2005) recommends school counselors implement a comprehensive school counseling program that “leads to increased student(s) achievement” (p. 11) and “supports the school’s academic mission” (p. 15) by calling attention “to situations within the schools that defeat, -

In Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy

Master of Science (MS) in Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy Deree – The American College of Greece has a long and honored tradition in psychology since 1966, being the first school in Greece to award a BA in Psychology. Since 2005 our graduate program in applied psychology has been training ethical, competitive and well educated professionals who find their own distinctive place within the profession of counseling psychology and other related disciplines in the area of mental health. The School of Graduate and Professional Education is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges through its Commission on Institutions of Higher Education. Master of Science (MS) in Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy Overview In the first year, the program aims to provide the student with core theoretical and research knowledge in areas relating to Counseling psychology is a branch of applied professional counseling psychology. In the second year, students enroll psychology concerned with the integration of different in skill-based courses from different theoretical orientations, psychological theories and research traditions within the are assigned to supervised practicum(s) (700 hours) and process of therapy. complete the research thesis. The MS in Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy Curriculum balances theoretical perspectives with the application of techniques and approaches, aiming to train students who wish to work with a variety of client/patient groups Required Courses in various settings. The program prepares participants to Year 1 conduct assessment, prevention, and interventions for Principles of Counseling & Personal Development psychological difficulties, and to serve the profession by Testing & Assessment offering high-quality services based on theory, high ethical Biological Basis of Behavior integrity, and empirically validated practices. -

Personal Construct Psychology

WHAT WE EXPECT WHAT WE GET WHAT WE GET How did we get to this…and how do we recover? NEW AND IMPROVED THEORY? OR….. SAME OLE’ THING…WITH A NEW LOOK. Ecclesiastes 1:9 Structure of Sanctuary “Given the evidence that treatments are about equally effective, that treatments WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT delivered in clinical settings are PSYCHOTHERAPY? AND WHAT IS THERE LEFT TO DEBATE? effective (and as effective as that BRUCE E. WAMPOLD, PH.D., provided in clinical trials), that ABPPZAC E. IMEL, PH.D. 2018 the manner in which treatments are provided are much more important than which treatment is provided, mandating particular treatments seems illogical.” “THE DEVELOPMENT OF A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP IS THE MOST ACCURATE INDICATOR OF A POSITIVE OUTCOME.” - J. ERIC GENTRY CARL ROGERS • January 1902-February 1987 • Person Centered Therapy • Unconditional Positive Regard + Congruence = Person Centered Treatment “I am not perfect…but I am enough.” PAUL D. MACLEAN • May 1913-December 2007 • Triune Brain • Three Distinct Brain Segments: Protoreptilian Paleomammalian Neomammalian “An interest in the brain requires no justification other than a curiosity to know why we are here, what we are doing here, and where we are going.” THE TRIUNE BRAIN Reptilian Brain Limbic Brain Neocortex ERIK ERIKSON • June 1902-May 1994 • Stages of Development • Development happens in stages with spectrum type “virutes” “Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive.” STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT • Traumatic Reenactment regresses an -

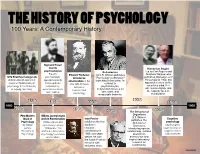

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

Department of Psychology & Counseling

Department of Psychology & Counseling 1 ABA503 Experimental Analysis of Behavior (3 Credits) DEPARTMENT OF This course introduces the experimental analysis of behavior, a natural science approach to the study of environment-behavior relations and PSYCHOLOGY & COUNSELING the foundation for applied behavior analysis. Topics discussed include respondent and operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement, Georgian Court University offers a Doctor of Psychology degree program stimulus control, choice, correspondence relations, verbal behavior and in School Psychology; Master of Arts degree programs in Clinical Mental the experimental procedures used to study them. Health Counseling, School Psychology, and Applied Behavior Analysis; a Prerequisite(s): Admission to the ABA or School Psychology graduate Certificate of Advanced Graduate Study in School Psychology, and a GCU programs or permission of the program director. Professional Counselor Certificate. Qualified candidates interested in any ABA504 Philosophy of Behaviorism (3 Credits) of these programs must submit all requirements for review (see individual This course introduces students to radical behaviorism as the programs for specific requirements). Admission to any of the programs philosophical foundation of behavior analysis and the implications of is contingent on the outcome of an interview with the program faculty. that philosophy for research and practice. Topics addressed will include Candidates will be notified in writing as to their status. a radical behavioral perspective of complex topics related to human learning including the mind, thinking, creativity, problem solving, and Programs cultural practices. • Applied Behavior Analysis, M.A. (http://catalog.georgian.edu/ Prerequisite(s): B- or better in ABA503. graduate/school-arts-sciences/psychology-counseling/applied- ABA505 Generalization & Training (3 Credits) behavior-analysis-ma/) An advanced seminar in Applied Behavior Analysis that will focus • Psychology, B.A./Applied Behavior Analysis, M.A.