Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment in Tarsal Somatic Dysfunction: a Case Study Joshua Batt, DO Michael M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skeletal Foot Structure

Foot Skeletal Structure The disarticulated bones of the left foot, from above (The talus and calcaneus remain articulated) 1 Calcaneus 2 Talus 3 Navicular 4 Medial cuneiform 5 Intermediate cuneiform 6 Lateral cuneiform 7 Cuboid 8 First metatarsal 9 Second metatarsal 10 Third metatarsal 11 Fourth metatarsal 12 Fifth metatarsal 13 Proximal phalanx of great toe 14 Distal phalanx of great toe 15 Proximal phalanx of second toe 16 Middle phalanx of second toe 17 Distal phalanx of second toe Bones of the tarsus, the back part of the foot Talus Calcaneus Navicular bone Cuboid bone Medial, intermediate and lateral cuneiform bones Bones of the metatarsus, the forepart of the foot First to fifth metatarsal bones (numbered from the medial side) Bones of the toes or digits Phalanges -- a proximal and a distal phalanx for the great toe; proximal, middle and distal phalanges for the second to fifth toes Sesamoid bones Two always present in the tendons of flexor hallucis brevis Origin and meaning of some terms associated with the foot Tibia: Latin for a flute or pipe; the shin bone has a fanciful resemblance to this wind instrument. Fibula: Latin for a pin or skewer; the long thin bone of the leg. Adjective fibular or peroneal, which is from the Greek for pin. Tarsus: Greek for a wicker frame; the basic framework for the back of the foot. Metatarsus: Greek for beyond the tarsus; the forepart of the foot. Talus (astragalus): Latin (Greek) for one of a set of dice; viewed from above the main part of the talus has a rather square appearance. -

Fractures of the Anterior Process of the Calcaneum; a Review and Proposed Treatment Algorithm

Foot and Ankle Surgery 25 (2019) 258–263 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Foot and Ankle Surgery journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fas Review Fractures of the anterior process of the calcaneum; a review and proposed treatment algorithm a, b b b b Baljinder S. Dhinsa *, Ahmed Latif , Roland Walker , Ali Abbasian , Diane Back , b Sam Singh a William Harvey Hospital, Kennington Road, Willesborough, Ashford TN24 0LZ, United Kingdom b Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT, United Kingdom A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Background: There remains a lack of recognition of these fractures, which leads to a delay in diagnosis and Received 18 June 2017 appropriate management. Received in revised form 1 February 2018 Methods: A comprehensive literature search was performed. Following inclusion and exclusion criteria, Accepted 3 February 2018 23 studies were available for analysis. Results: Delay in diagnosis is common and has a negative impact on outcome. If an APC fracture is Keywords: suspected; anteroposterior, lateral and oblique plain radiographs should be requested. Further Fracture investigation with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is indicated if plain Calcaneum radiographs are inconclusive and patient remains symptomatic. Non-operative measures are usually Anterior process Avulsion adequate for most undisplaced fractures, however surgical intervention maybe required for large, intra- Compression articular fractures in the acute setting and for non-union. Calcaneocuboid Conclusions: A treatment algorithm is suggested that may help with the diagnosis and management of these injuries. -

Morphological and Biomechanical Implications of Cuboid Facet of the Navicular Bone in the Gait

Int. J. Morphol., 37(4):1397-1403, 2019. Morphological and Biomechanical Implications of Cuboid Facet of the Navicular Bone in the Gait Implicaciones Morfológicas y Biomecánicas de la Faceta Cuboídea del Navicular en la Marcha Eduardo Saldías1; Assumpció Malgosa1; Xavier Jordana1 & Albert Isidro2 SALDÍAS, E.; MALGOSA, A.; JORDANA, X. & ISIDRO, A. Morphological and biomechanical implications of cuboid facet of the navicular bone in the gait. Int. J. Morphol., 37(4):1397-1403, 2019. SUMMARY: The cuboid facet of the navicular bone is an irregular flat surface, present in non-human primates and some human ancestors. In modern humans, it is not always present and it is described as an “occasional finding”. To date, there is not enough data about its incidence in ancient and contemporary populations, nor a biomechanical explanation about its presence or absence. The aim of the study was to evaluate the presence of the cuboid facet in ancient and recent populations, its relationship with the dimensions of the midtarsal bones and its role in the biomechanics of the gait. 354 pairs of naviculars and other tarsal bones from historical and contemporary populations from Catalonia, Spain, have been studied. We used nine measurements applied to the talus, navicular, and cuboid to check its relationship with facet presence. To analyze biomechanical parameters of the facet, X-ray cinematography was used in living patients. The results showed that about 50 % of individuals developed this surface without differences about sex or series. We also observed larger sagittal lengths of the talar facet (LSAGTAL) in navicular bones with cuboid facet. No significant differences were found in the bones contact during any of the phases of the gait. -

Bones of the Upper and Lower Limb

Bones of the Upper and Lower limb Musculoskeletal block- Anatomy-lecture 1 Editing file Objectives Color guide : important in Red ✓ Classify the bones of the three regions of the lower Doctor note in Green limb (thigh, leg and foot). Extra information in Grey ✓ Memorize the main features of the – Bones of the thigh (femur & patella) – Bones of the leg (tibia & Fibula) – Bones of the foot (tarsals, metatarsals and phalanges) ✓ Recognize the side of the bone. Note: this lecture is based on female slides since Prof abuel makarem said only things that are mentioned in the female slides will come in the exam Note : All bones picture which are described in this lecture are bones on the right side of the body Before start :Please make yourself familiar with these terms to better understand the lecture Terms Meaning Example Ridge The long and narrow upper edge, angle, or crest The supracondylar ridges (in the distal part of of something (the humerus The trochlear notch (in the proximal part of the Notch An indentation, (incision) on an edge or surface (ulna A nodule or a small rounded projection on the Tubercles (Dorsal tubercle (in the distal part of the radius bone A hollow place (The Notch is not complete but the Subscapular fossa (in the concave part of the Fossa fossa is complete and both of them act as the lock (scapula (of the joint A large prominence on a bone usually serving for Deltoid tuberosity (in the humorous) and it Tuberosity the attachment of muscles or ligaments (is a connects the deltoid muscle (bigger projection than the Tubercle -

Multiplanar CT Analysis of Fifth Metatarsal Morphology

FAIXXX10.1177/1071100715623041Foot & Ankle InternationalDeSandis et al 623041research-article2015 Article Foot & Ankle International® 2016, Vol. 37(5) 528 –536 Multiplanar CT Analysis of Fifth Metatarsal © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Morphology: Implications for Operative DOI: 10.1177/1071100715623041 Management of Zone II Fractures fai.sagepub.com Bridget DeSandis, BA1, Conor Murphy, MD2, Andrew Rosenbaum, MD1, Matthew Levitsky, BA1, Quinn O’Malley1, Gabrielle Konin, MD1, and Mark Drakos, MD1 Abstract Background: Percutaneous internal fixation is currently the method of choice treating proximal zone II fifth metatarsal fractures. Complications have been reported due to poor screw placement and inadequate screw sizing. The purpose of this study was to define the morphology of the fifth metatarsal to help guide surgeons in selecting the appropriate screw size preoperatively. Methods: Multiplanar analysis of fifth metatarsal morphology was completed using computed tomographic (CT) scans from 241 patients. Specific parameters were analyzed and defined in anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views including metatarsal length, distance from the base to apex of curvature, apex medullary canal width, apex height, and fifth metatarsal angle. Results: The average metatarsal length in the AP view was 71.4 ± 6.1 mm and in the lateral view 70.4 ± 6.0 mm, with 95% of patients having lengths between 59.3 and 83.5 mm and 58.4 and 82.4 mm, respectively. The average canal width at the apex of curvature was 4.1 ± 0.9 mm in the AP view and 5.3 ± 1.1 mm in the lateral view, with 95% of patients having widths between 2.2 and 5.9 mm and 3.2 and 7.5 mm, respectively. -

Rethinking the Evolution of the Human Foot: Insights from Experimental Research Nicholas B

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174425. doi:10.1242/jeb.174425 REVIEW Rethinking the evolution of the human foot: insights from experimental research Nicholas B. Holowka* and Daniel E. Lieberman* ABSTRACT presumably owing to their lack of arches and mobile midfoot joints Adaptive explanations for modern human foot anatomy have long for enhanced prehensility in arboreal locomotion (see Glossary; fascinated evolutionary biologists because of the dramatic differences Fig. 1B) (DeSilva, 2010; Elftman and Manter, 1935a). Other studies between our feet and those of our closest living relatives, the great have documented how great apes use their long toes, opposable apes. Morphological features, including hallucal opposability, toe halluces and mobile ankles for grasping arboreal supports (DeSilva, length and the longitudinal arch, have traditionally been used to 2009; Holowka et al., 2017a; Morton, 1924). These observations dichotomize human and great ape feet as being adapted for bipedal underlie what has become a consensus model of human foot walking and arboreal locomotion, respectively. However, recent evolution: that selection for bipedal walking came at the expense of biomechanical models of human foot function and experimental arboreal locomotor capabilities, resulting in a dichotomy between investigations of great ape locomotion have undermined this simple human and great ape foot anatomy and function. According to this dichotomy. Here, we review this research, focusing on the way of thinking, anatomical features of the foot characteristic of biomechanics of foot strike, push-off and elastic energy storage in great apes are assumed to represent adaptations for arboreal the foot, and show that humans and great apes share some behavior, and those unique to humans are assumed to be related underappreciated, surprising similarities in foot function, such as to bipedal walking. -

Common Stress Fractures BRENT W

COVER ARTICLE PRACTICAL THERAPEUTICS Common Stress Fractures BRENT W. SANDERLIN, LCDR, MC, USNR, Naval Branch Medical Clinic, Fort Worth, Texas ROBERT F. RASPA, CAPT, MC, USN, Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Jacksonville, Florida Lower extremity stress fractures are common injuries most often associated with partic- ipation in sports involving running, jumping, or repetitive stress. The initial diagnosis can be made by identifying localized bone pain that increases with weight bearing or repet- itive use. Plain film radiographs are frequently unrevealing. Confirmation of a stress frac- ture is best made using triple phase nuclear medicine bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Prevention of stress fractures is most effectively accomplished by increasing the level of exercise slowly, adequately warming up and stretching before exercise, and using cushioned insoles and appropriate footwear. Treatment involves rest of the injured bone, followed by a gradual return to the sport once free of pain. Recent evidence sup- ports the use of air splinting to reduce pain and decrease the time until return to full par- ticipation or intensity of exercise. (Am Fam Physician 2003;68:1527-32. Copyright© 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians) tress fractures are among the involving repetitive use of the arms, such most common sports injuries as baseball or tennis. Stress fractures of and are frequently managed the ribs occur in sports such as rowing. by family physicians. A stress Upper extremity and rib stress fractures fracture should be suspected in are far less common than lower extremity Sany patient presenting with localized stress fractures.1 bone or periosteal pain, especially if he or she recently started an exercise program Etiology and Pathophysiology or increased the intensity of exercise. -

Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Iliotibial Band Pain Secondary to a Hypomobile Cuboid in a 24-Year-Old Female Tri-Athlete

INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY OF ORTHOPEDIC MEDICINE VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 WINTER 2015/2016 Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Iliotibial Band Pain Secondary to a Hypomobile Cuboid in a 24-Year-Old Female Tri-Athlete Femoroacetabular Impingement in the Adolescent Population: A Review Immediate Changes in Widespread Pressure Pain Sensitivity, Neck Pain, and Cervical Spine Range of Motion after Cervical or Thoracic Thrust Manipulation in Patients with Bilateral Chronic Mechanical Neck Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial IAOM-US CONNECTION DIRECTORY is published by John Hoops PT, COMT The International Managing Editor Academy of Orthopedic Medicine-US (IAOM-US) Valerie Phelps PT, ScD, OCS, FAAOMPT PO Box 65179 Chief Editor / Education Director Tucson, AZ 85728 (p) 866.426.6101 Tanya Smith PT, ScD, FAAOMPT (f) 866.698.4832 Senior Editor (e) [email protected] (w) www.iaom-us.com John Woolf MS, PT, ATC, COMT Business Director CONTACT (p) 866.426.6101 Sharon Fitzgerald (f) 866.698.4832 Executive Assistant (e) [email protected] (w) www.iaom-us.com Andrea Cameron All trademarks are the property Administrative Assistant/ of their respective owners. Marketing Liaison The IAOM-US CONNECTION VOLUME 4 CONNECTION Differential Diagnosis and Dear Colleagues: Treatment of Iliotibial Band Pain Secondary to a Hypomobile Cuboid We hope you’ve had a happy and healthy 2015 2 in a 24-Year-Old Female Tri-Athlete and are ready to set your sights on 2016. Our 2016 course schedule is set, though we’re always adding new course locations and topics. If you haven’t had a chance to see what’s coming to your neck of the woods, here’s a link to the schedule. -

Metric and Non Metric Characteristics of Human Forefoot: a Radiological Study in Egyptian Population

Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2019 February; 13(2): pages 46-54 DOI: 10.22587/ajbas.2019.13.2.6 Original paper AENSI Publications Journal home page: www.ajbasweb.com Metric and Non metric characteristics of human forefoot: A radiological study in Egyptian population Samah Mohammed, Mahmoud Abozaid and Fatma Elzahraa, Fouad Abd Elbaky Department of Anatomy, Faculty of medicine, Minia University, Minia, Egypt. Correspondence Author: Samah Mohammed, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of medicine, Minia University, Minia, Egypt. Received date: 1 January 2019, Accepted date: 15 January 2018, Online date: 28 February 2019 Copyright: © 2019 Samah Mohammed et al, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Human forefoot is composed of metatarsal bones and phalanges. Their morphology and dimensions are important for proper bipedal locomotor function. Structural defects affecting forefoot bones result in foot dysfunction. The aim of the present study is to describe the morphology of the bones of forefoot and to measure their lengths and widths. A digital radiographic study was conducted on right and left feet of 100 healthy individuals (50 males and 50 females) above 21 years old. Inspection of the forefoot bones using radiographs was done to describe general shapes of bones. The lengths and widths of metatarsal bone and phalanges were measured using Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. Mean and standard deviations were obtained for all measurements of each side of both sexes. -

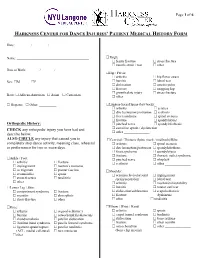

Harkness Center for Dance Injuries' Patient Medical History Form

Page 1 of 6 HARKNESS CENTER FOR DANCE INJURIES’ PATIENT MEDICAL HISTORY FORM Date: ________ / ________ / ________ Name: __________________________________________ Thigh: femur fracture stress fracture muscle strain / tear other_______________ Date of Birth: _______ / _______ / _______ Hip / Pelvis: arthritis hip flexor strain Sex: M F bursitis labral tear dislocation osteitis pubis fracture snapping hip growth plate injury stress fracture Race: African-American Asian Caucasian other _______________ Hispanic Other: __________ Lumbar-Sacral Spine (low back): arthritis sciatica disc herniation/protrusion scoliosis facet syndrome spinal stenosis fracture spondylolysis Orthopedic History: pinched nerve spondylolisthesis CHECK any orthopedic injury you have had and sacroiliac sprain / dysfunction other _______________ describe below. ALSO CIRCLE any injury that caused you to Cervical / Thoracic Spine (neck / mid back)/Ribs: completely stop dance activity, meaning class, rehearsal arthritis spinal stenosis or performance for two or more days. disc herniation/protrusion spondylolisthesis facet syndrome spondylolysis fracture thoracic outlet syndrome Ankle / Foot: pinched nerve whiplash arthritis fracture scoliosis other _______________ impingement morton’s neuroma os trigonum plantar fasciitis Shoulder: sesamoiditis sprain acromioclavicular joint impingement stress fracture tendinitis sprain/separation labral tear other________________ arthritis mechanical instability Lower Leg / Shin: -

A Morphometric and Morphological Study on Dry Adult Cuboid Bones

Review Article Clinician’s corner Images in Medicine Experimental Research Case Report Miscellaneous Letter to Editor DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2021/47259.14447 Original Article Postgraduate Education A Morphometric and Morphological Case Series Study on Dry Adult Cuboid Bones Research Protocol Anatomy Section Short Communication SREYA MOITRA ABSTRACT software, version 19. Students t-test was applied to find the Introduction: Precise biometric data of cuboid and difference between the mean values of the parameters. calcaneocuboid joint are not discussed very distinctly in the text Results: Mean medial length of cuboid was 33.41 mm, lateral books of Anatomy. A better knowledge of the joint surfaces of length was 19.73 mm, height was 26.17 mm, length index cuboid and biometric data would generate a three dimensional was 169.33, vertical and transverse diameters of calcaneal modeling of the calcaneocuboid joint and would help in the articular facet were 24.24 mm and 16.45 mm respectively, vertical and transverse diameters of metatarsal articular facet management of Cuboid Syndrome. were 21.32 mm and 13.85 mm respectively, depth of peroneal Aim: To study about morphological and morphometric analysis groove was 0.63mm. Concavo-convex facet with posteromedial in adult dry cuboid bone. projection and oval or reniform in shape (Type 1A) was the most Materials and Methods: This study was conducted in the common calcaneal articular facet and convex pattern was the Department of Anatomy of a Medical College using 60 dry most common metatarsal articular facet of cuboid. cuboid bones from museum. Each bone was observed for its Conclusion: Morphological characterisation of articular facet morphometric analysis as well as its pattern of calcaneal and of cuboid and its morphometric analysis help to understand the metatarsal articular facets. -

Clinical Anatomy of the Lower Extremity

Государственное бюджетное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «Иркутский государственный медицинский университет» Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации Department of Operative Surgery and Topographic Anatomy Clinical anatomy of the lower extremity Teaching aid Иркутск ИГМУ 2016 УДК [617.58 + 611.728](075.8) ББК 54.578.4я73. К 49 Recommended by faculty methodological council of medical department of SBEI HE ISMU The Ministry of Health of The Russian Federation as a training manual for independent work of foreign students from medical faculty, faculty of pediatrics, faculty of dentistry, protocol № 01.02.2016. Authors: G.I. Songolov - associate professor, Head of Department of Operative Surgery and Topographic Anatomy, PhD, MD SBEI HE ISMU The Ministry of Health of The Russian Federation. O. P.Galeeva - associate professor of Department of Operative Surgery and Topographic Anatomy, MD, PhD SBEI HE ISMU The Ministry of Health of The Russian Federation. A.A. Yudin - assistant of department of Operative Surgery and Topographic Anatomy SBEI HE ISMU The Ministry of Health of The Russian Federation. S. N. Redkov – assistant of department of Operative Surgery and Topographic Anatomy SBEI HE ISMU THE Ministry of Health of The Russian Federation. Reviewers: E.V. Gvildis - head of department of foreign languages with the course of the Latin and Russian as foreign languages of SBEI HE ISMU The Ministry of Health of The Russian Federation, PhD, L.V. Sorokina - associate Professor of Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation at ISMU, PhD, MD Songolov G.I K49 Clinical anatomy of lower extremity: teaching aid / Songolov G.I, Galeeva O.P, Redkov S.N, Yudin, A.A.; State budget educational institution of higher education of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation; "Irkutsk State Medical University" of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation Irkutsk ISMU, 2016, 45 p.