Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Iliotibial Band Pain Secondary to a Hypomobile Cuboid in a 24-Year-Old Female Tri-Athlete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

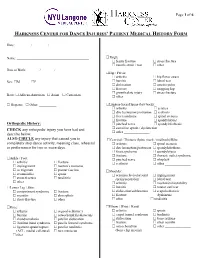

Harkness Center for Dance Injuries' Patient Medical History Form

Page 1 of 6 HARKNESS CENTER FOR DANCE INJURIES’ PATIENT MEDICAL HISTORY FORM Date: ________ / ________ / ________ Name: __________________________________________ Thigh: femur fracture stress fracture muscle strain / tear other_______________ Date of Birth: _______ / _______ / _______ Hip / Pelvis: arthritis hip flexor strain Sex: M F bursitis labral tear dislocation osteitis pubis fracture snapping hip growth plate injury stress fracture Race: African-American Asian Caucasian other _______________ Hispanic Other: __________ Lumbar-Sacral Spine (low back): arthritis sciatica disc herniation/protrusion scoliosis facet syndrome spinal stenosis fracture spondylolysis Orthopedic History: pinched nerve spondylolisthesis CHECK any orthopedic injury you have had and sacroiliac sprain / dysfunction other _______________ describe below. ALSO CIRCLE any injury that caused you to Cervical / Thoracic Spine (neck / mid back)/Ribs: completely stop dance activity, meaning class, rehearsal arthritis spinal stenosis or performance for two or more days. disc herniation/protrusion spondylolisthesis facet syndrome spondylolysis fracture thoracic outlet syndrome Ankle / Foot: pinched nerve whiplash arthritis fracture scoliosis other _______________ impingement morton’s neuroma os trigonum plantar fasciitis Shoulder: sesamoiditis sprain acromioclavicular joint impingement stress fracture tendinitis sprain/separation labral tear other________________ arthritis mechanical instability Lower Leg / Shin: -

Cuboid Syndrome in a College Basketball Player: a Case Report

CASE REVIEW Joseph J. Piccininni, Report Editor Cuboid Syndrome in a College Basketball Player: A Case Report Stephanie M. Mazerolle, PhD, ATC • University of Connecticut UBOID SYNDROME is a condition involv- Table 1. Clinical Presentation ing some degree of disruption of the of Cuboid Subluxation C normal structural congruity of the calca- • No edema or discoloration neo-cuboid (CC) joint.1-3 The condition is associated with several clinical terms for • Pain that may radiate to heel, mimicking heel spur midfoot pathology, including cuboid fault syndrome, pain dropped cuboid, subluxed cuboid, and lateral plantar • May or may not present with palpable defect in neuritis. The literature suggests that cuboid subluxation plantar fascia is associated with a lateral ankle sprain mechanism, • Point tenderness at calcaneo-cuboid joint and styloid occurring most often with a combination of inversion process of 5th metatarsal and plantar flexion.4 The inversion ankle sprain is the • Inability to “work through” the pain during the push- most common athletic injury, which accounts for 10- off phase of the gait cycle 15% of all sport participation time lost to injury.5 • Increased pain with stair climbing 1 Cuboid subluxations and dislocations are rare. The • Increased pain with side-to-side movements or majority of such cases reported in the literature have lateral movements involved long distance runners and ballet dancers.1,4 CC joint dysfunction following a traumatic episode usually results from a dislocation or subluxation injury, but lateral aspect of the foot. She reported having expe- foot pain and chronic instability of the lateral column rienced a traumatic episode three weeks earlier. -

Patient Medical History Form

Date of Visit: ________ / ________ / ________ ID # (R=Research) +MR# Patient Medical History Form Name: __________________________________________ Knee: arthritis osgood-schlatter’s Date of Birth: _______ / _______ / _______ Sex: M F bursitis osteochondritis dissecans Social Security ______-_____-________ chondromalacia patellar dislocation iliotibial band syndrome patella femoral syndrome Race: African-American Asian Caucasian ligament sprain/rupture patellar tendinitis Hispanic Other: __________ (ACL, medial collateral) torn meniscus other________________ Address:___________________________________________ ______________________________________________ Thigh: femur fracture stress fracture City: _________________ State: _______ ZIP: ________ muscle strain / tear other_______________ Primary Phone: _______ - ________ - __________ Hip / Pelvis: Email: ___________________________________________ arthritis hip flexor strain bursitis labral tear Emergency Contact Information: dislocation osteitis pubis Name: ___________________________________________ fracture snapping hip growth plate injury stress fracture Relation: ______________ Phone:_____________________ other _______________ Health Insurance Information: Lumbar-Sacral Spine (low back): Name of Insurance Co: _____________________________ arthritis sciatica Name of Policy Holder: _____________________________ disc herniation/protrusion scoliosis facet syndrome spinal stenosis Policy #: _________________ Group#: ________________ fracture spondylolsysis -

Management Strategies for Cuboid Syndrome

CASE REVIEW Joe J. Piccininni, EdD, CAT(C) Management Strategies for Cuboid Syndrome Jennifer L. Roney, MS, ATC • University of Utah; Melissa L. Yamashiro, ATC • Orthopedic Specialty Group; and Charlie A. Hicks-Little, PhD, ATC • University of Utah Cuboid syndrome refers to a subluxation and Woodle3 reported that nearly all cases of the cuboid or calcaneo-cuboid joint dys- of cuboid syndrome were associated with function.1,2 Cuboid syndrome only accounts pes planus. Pronation of the subtalar joint for 4% of sports-related foot injuries, but provides the peroneal longus muscle with a represents 17% of foot injuries among ballet greater mechanical advantage.5 The intrinsic dancers.2,3 The purpose of this report is to foot muscles, predominantly the flexors, are present an effective management strategy believed to play an important role in stabiliz- for cuboid syndrome. ing the transverse tarsal joint during gait.4 The stability of the Current conservative management of Key PointsPoints articulation between the cuboid syndrome includes manual therapy, Cuboid syndrome is rarely found in ath- cuboid and the distal taping, padding, and use of an orthosis.5-10 letes, other than ballet dancers. portion of the calca- Newell and Woodle3 described a cuboid neus is maintained by manipulation technique that was later Current management options include a number of ligaments referred to as the “black snake heel whip.”1 manual techniques, taping, padding, and and a joint capsule. The patient stands with the affected leg in orthotics. The peroneus longus a knee-flexed, non-weight-bearing position. tendon runs through The clinician grasps the forefoot, placing the The “four mini-stirrup” taping can help the peroneal groove on thumbs on the plantar aspect of the cuboid manage cuboid syndrome. -

Overuse Injuries & Special Skeletal Injuries Dr M.Taghavi

Overuse Injuries & special skeletal injuries Dr M.Taghavi Director of sport medicine center of olympic academy Created with Print2PDF. To remove this line, buy a license at: http://www.software602.com/ Prevalence of Overuse Injuries 30 to 50% of all sport injuries are from overuse In some sports such as distance running, swimming, rock climbing ,and pitching the majority of injuries are from overuse Created with Print2PDF. To remove this line, buy a license at: http://www.software602.com/ Examples of Overuse Injuries Tendonitis Tenosynovitis Shin splints = posterior tibial tendonitis Cuboid Syndrome Patellar alignment and compression syndromes Runner’s knee = illiotibial band tendonitis Created with Print2PDF. To remove this line, buy a license at: http://www.software602.com/ Examples of Overuse Injuries Swimmer’s shoulder and pitcher’s shoulder = rotator cuff tendonitis Pitcher’s or little league elbow = flexor/pronator tendonitis; medial epicondylitis Stress fracture Osgood Schlatter Disease Calcaneal Apophysitis Created with Print2PDF. To remove this line, buy a license at: http://www.software602.com/ Examples of Overuse Injuries Jumper’s Knee = Patellar tendonitis Plantar Fascitis/Heal Spur Syndrome Created with Print2PDF. To remove this line, buy a license at: http://www.software602.com/ Causes of Overuse Injuries Training errors Muscle imbalance Lack of flexibility Malalignment of body structures Over training Poor equipment Poor foot mechanics (over pronation) Created with Print2PDF. To remove this line, buy a license at: http://www.software602.com/ Prevention of Overuse Injuries Slow progression in training overload Increase training overload no more than 10% per week Improve flexibility Improve muscle strength in agonist vs. antagonist muscles Look for worn out equipment/shoes Created with Print2PDF. -

Ankle Injuries

Sport & Exercise Medicine Ankle Injury Differential Resident Guidebook Ankle Injuries Achilles tendon sprain/tear Peroneal tendinopathy Extensor Hallucis Longus Tenosynovitis Peroneal subluxation Weber Fracture Stress fracture Calcaneal bursitis Calcaneal fracture Base of 5th metatarsal fracture/stress fracture/Jones fracture/Pseudo-Jones Medial Tibial Stress syndrome/ reaction/fracture Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction Tibialis Anterior Tenosynovitis Tibialis Posterior tendinopathy Synovitis FHL tendinitis Posterior tibial artery pseudoaneurysm Referred Pain Image retrieved from: https://humananatomycharty.com/anatomy-of-the-foot-ligaments- and-tendons/anatomy-of-the-foot-ligaments-and-tendons-foot-anatomy-tendons-ankle- anatomy-ligaments-and-tendons-ankle/ Dr. A Francella MD CCFP, Dr. Neil Dilworth CCFP (SEM, EM), Dr. Mark Leung CCFP (SEM) 1 Sport & Exercise Medicine Ankle Injury Differential Resident Guidebook Syndesmotic sprain/tear AITFL Sprain/Tear Anterior Impingement Anterolateral Impingement PITFL Sprain/Tear Posterior Impingement PTFL Sprain/Tear Os trigonum syndrome Referred pain CFL Sprain/Tear Sinus Tarsi Coarctation of talocalcaneal ATFL Sprain/Tear Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability Gout Cuboid avulsion fracture Pseudogout Cuboid syndrome Talar dome fracture Osteochondritis dissecans Pilon/Plafond fracture Osteochondral defect Deltoid Sprain/Tear Spring ligament sprain/tear Navicular fracture Navicular impingement Os Naviculare synchondrosis Coarctation of calcaneonavicular Images retrieved from: Dr. A Francella MD CCFP, -

Preventing Musculoskeletal Injury (MSI) for Musicians and Dancers

Preventing Musculoskeletal Injury (MSI) for Musicians and Dancers A Resource Guide Preventing Musculoskeletal Injury (MSI) for Musicians and Dancers A Resource Guide June 6, 2002 About SHAPE SHAPE (Safety and Health in Arts Production and Entertainment) is an industry association dedicated to promoting health and safety in film and television production, theatre, dance, music, and other performing arts industries in British Columbia. SHAPE provides information, education, and other services that help make arts production and entertainment workplaces healthier and safer. For more information, contact: SHAPE (Safety and Health in Arts Production and Entertainment) Suite 280–1385 West 8th Avenue Vancouver, BC V6H 3V9 Phone: 604 733-4682 in the Lower Mainland 1 888 229-1455 toll-free Fax: 604 733-4692 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.shape.bc.ca © 2002 Safety and Health in Arts Production and Entertainment (SHAPE). All rights reserved. SHAPE encourages the copying, reproduction, and distribution of this document to promote health and safety in the workplace, provided that SHAPE is acknowledged. However, no part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, or distributed for profit or other commercial enterprise, nor may any part be incorporated into any other publication, without written permission of SHAPE. National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Robinson, Dan. Preventing musculoskeletal injury (MSI) for musicians and dancers : a resource guide Writers: Dan Robinson, Joanna Zander and B.C. Research. Cf. Acknowledgments. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-4801-8 1. Musculoskeletal system - Wounds and injuries - Prevention. 2. Entertainers - Wounds and injuries - Prevention. 3. Musicians - Wounds and injuries - Prevention. -

The Cuboid Syndrome

Physical Rehabilitation & Sports Medicine 333 W. Cordova Santa Fe NM 87505 • Tel. 505.984.9101 Fax. 505.984.8998 Bruce Mazur, DC, PT Kent Chou, PT Erik De Proost, DPT, OCS, COMT, Cert. MDT Melinda Ramirez, MPT Jackie Ray, DPT The Cuboid Syndrome The cuboid syndrome consists of a subluxation of the cuboid at the cuboid- calcaneal joint and the cuboid-navicular-lateral cuneiform joint whereby the cuboid is ‘locked’ in a more medial rotated and plantar position (everted). This condition is most often seen in the athletic population (ballet, basketball, running,..). It can be caused by inversion trauma, but also by overuse such as excessive ‘sur les pointes’ movements with ballet dancers. Possible injury mechanism: A sudden reflex-contraction of the peroneus longus (that passes in the peroneal sulcus on the plantar side of the cuboid) in response to an inversion trauma, causes a rotational force on the cuboid. This rotational force pulls the lateral side of the cuboid dorsal- lateral and the medial side of the cuboid medial – plantar resulting in an everted position of the cuboid. (Fig. 1).The cuboid can stay ‘locked’ in this position and become a source of pain and mechanical derangement. Another injury mechanism involves repetitive peroneus longus contractions during for example ‘sur les pointes’ movements. They can cause progressive laxicity of the interosseus ligaments of the calcaneo-cuboid joint and/ or in the cuboid-lateral cuneiform- navicular joints, predisposing the cuboid to a subluxation. Navicular Lateral cuneiform Cuboid Fig. 1: Direction of cuboid subluxation Presentation: A patient with cuboid syndrome will usually complain of pain on the dorsal or plantar side of the cuboid area with some referred pain into the 4th and 5th ray. -

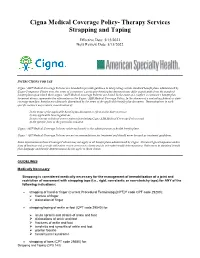

Strapping and Taping

Cigna Medical Coverage Policy- Therapy Services Strapping and Taping Effective Date: 5/15/2021 Next Review Date: 5/15/2022 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which these Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies are based. In the event of a conflict, a customer’s benefit plan document always supersedes the information in the Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policy. In the absence of a controlling federal or state coverage mandate, benefits are ultimately determined by the terms of the applicable benefit plan document. Determinations in each specific instance may require consideration of: 1) the terms of the applicable benefit plan document in effect on the date of service 2) any applicable laws/regulations 3) any relevant collateral source materials including Cigna-ASH Medical Coverage Policies and 4) the specific facts of the particular situation Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies relate exclusively to the administration of health benefit plans. Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies are not recommendations for treatment and should never be used as treatment guidelines. Some information in these Coverage Policies may not apply to all benefit plans administered by Cigna. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and -

The Lateral Column Compression Syndrome Appears to Be the Underlying Movement Impairment Syndrome That Drives Many Seemingly Unrelated Foot and Ankle Overuse Injuries

10/16/2014 Lateral Column Compression Syndrome Pieter Kroon PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT Tim Kruchowsky PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT Cuboid Syndrome • Cuboid syndrome is defined as a minor disruption or subluxation of the structural congruity of the calcaneocuboid joint. • It is a poorly understood condition in both the athletic and non-athletic population and therefore, is often misdiagnosed and mistreated. • Current treatment approaches fix the acute symptoms, but not the underlying cause of the problem, which leaves the patient vulnerable to repeat injuries. Patterson S. Cuboid syndrome: a review of the literature. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (2006) 5,597-606 Etiology Extrinsic trauma: • Isolated fractures are rare • The mechanism of injury is usually plantarflexion of the hindfoot and midfoot against a fixed forefoot. • The term “nutcracker fracture” describes compression of the cuboid between the calcaneus and the 4th and 5th MT. • Plantar flexion/inversion sprains account for the majority of the cases reported. Greaney RB, Gerber FH, Laughlin RL, et al (1983) Distribu- tion and natural history of stress fractures in US marine re- cruits. Radiology 146:339–346 1 10/16/2014 Etiology Intrinsic trauma: • Repeated microtrauma injuries are rarely described in the literature, merely mentioned • A retrospective study by Yu et al. found the incidence of cuboid stress fractures in the 4% range over a 19 year period. • Reported hypotheses on the causes of cuboid stress fractures: • Repeated pull of the peroneal tendons • Malalignment with altered biomechanics • Insufficiency fractures resulting from a loss of bone density • Overpronation of the foot • Calf muscle inflexibility Yale J (1976) A statistical analysis of 3,657 consecutive fatigue fractures of the distal lower extremities. -

Examination and Treatment of Cuboid Syndrome: a Literature Review

Durall Nov • Dec 2011 [ Sports Physical Therapy ] Examination and Treatment of Cuboid Syndrome: A Literature Review Chris J. Durall, DPT, ATC, MSPT* Context: Cuboid syndrome is thought to be a common source of lateral midfoot pain in athletes. Evidence Acquisition: A Medline search was performed via PubMed (through June 2010) using the search terms cuboid, syndrome, subluxed, locked, fault, dropped, peroneal, lateral, plantar, and neuritis with the Boolean term AND in all possi- ble combinations. Retrieved articles were hand searched for additional relevant references. Results: Cuboid syndrome is thought to arise from subtle disruption of the arthrokinematics or structural congruity of the calcaneocuboid joint, although the precise pathomechanic mechanism has not been elucidated. Fibroadipose synovial folds (or labra) within the calcaneocuboid joint may play a role in the cause of cuboid syndrome, but this is highly specu- lative. The symptoms of cuboid syndrome resemble those of a ligament sprain. Currently, there are no definitive diagnostic tests for this condition. Case reports suggest that cuboid syndrome often responds favorably to manipulation and/or exter- nal support. Conclusions: Evidence-based guidelines regarding cuboid syndrome are lacking. Consequently, the diagnosis of cuboid syndrome is often based on a constellation of signs and symptoms and a high index of suspicion. Unless contraindicated, manipulation of the cuboid should be considered as an initial treatment. Keywords: cuboid; syndrome; subluxed; midfoot uboid syndrome is an easily misdiagnosed source of calcaneal process acting as a pivot.3,15 The rotation has been lateral midfoot pain, and is believed to arise from a described as pronation/supination and obvolution/involution.3,15 Csubtle disruption of the arthrokinematics or structural Inversion/eversion is used herein. -

The “Leonardo Perspective “ 2 Jobs of the Foot Stabilization Principles

3/30/2017 Russ Bartholomew PT ,DPT OCS 8:00-8:30 Overview of key principles from Day 1 8:30 -10:00 Gait assessment 10:00- 11:00 Plantar Fasciitis 11:00-12:30 Meeting 12:30-1:30 Lunch 1:30 -2:30Achilles Tendinopathy 2:30 – 4:00 Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction , Bunionectomy , Hallux rigidus 4:00 – 5:00 Cuboid Syndrome and Sinus Tarsi Syndrome 5:00 to end ,Exercise Lab The “Leonardo Perspective “ 2 jobs of the foot Stabilization Principles Applied to the Foot ( intrinsics, near extrinsic , distant extrinsic) 1)Closed Chain Dorsiflexion Motor Learning 2)Knee Flexion at Loading Response Fryette’s Law of the Foot 3)Hip extension at terminal stance The torque converter concept of subtalar joint First ray stability STJN Magnetic North 1 3/30/2017 Gait Lab Foundation before roof Closed chain is the destination Facilitation versus strengthening Top down AND bottom up ( “The butt is the steering wheel of the foot “) Tri-Plane Stabilization principles / ( Not excessive pronation but lack of pronation control (Jam 2006 ) 2 3/30/2017 Pain as a guideline Is it really an “Itis “ ? ( If not why use anti- inflammatory treatment modalities ?) Add what is missing /create the environment. Self efficacy (The patient must understand and be educated in order to be expected to be compliant) 3 3/30/2017 TENSION (abnormal foot position or compensation for loss of flexibility . Surface of walking and running , shoe issues , weight gain. DOSAGE ( frequency , distance , speed or weight) Loss of lengthening of the Achilles complex/mechanical loss of dorsiflexion. (Tension) Eccentric weakness of the Achilles complex ( Tension) Excessive Prolonged Pronation (EPP).