The All-India Progressive Writers' Association: the Indian Phase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Volume 1 on Stage/ Off Stage

lives of the women Volume 1 On Stage/ Off Stage Edited by Jerry Pinto Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media Supported by the Laura and Luigi Dallapiccola Foundation Published by the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media, Sophia Shree B K Somani Memorial Polytechnic, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026 All rights reserved Designed by Rohan Gupta be.net/rohangupta Printed by Aniruddh Arts, Mumbai Contents Preface i Acknowledgments iii Shanta Gokhale 1 Nadira Babbar 39 Jhelum Paranjape 67 Dolly Thakore 91 Preface We’ve heard it said that a woman’s work is never done. What they do not say is that women’s lives are also largely unrecorded. Women, and the work they do, slip through memory’s net leaving large gaps in our collective consciousness about challenges faced and mastered, discoveries made and celebrated, collaborations forged and valued. Combating this pervasive amnesia is not an easy task. This book is a beginning in another direction, an attempt to try and construct the professional lives of four of Mumbai’s women (where the discussion has ventured into the personal lives of these women, it has only been in relation to the professional or to their public images). And who better to attempt this construction than young people on the verge of building their own professional lives? In learning about the lives of inspiring professionals, we hoped our students would learn about navigating a world they were about to enter and also perhaps have an opportunity to reflect a little and learn about themselves. So four groups of students of the post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media, SCMSophia’s class of 2014 set out to choose the women whose lives they wanted to follow and then went out to create stereoscopic views of them. -

Literary Criticism and Literary Historiography University Faculty

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected]) Title Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms. First Name Ali Last Name Javed Photograph Designation Reader/Associate Professor Department Urdu Address (Campus) Department of Urdu, Faculty of Arts, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 (Residence) C-20, Maurice Nagar, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666627 (Residence)optional 27662108 Mobile 9868571543 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. JNU, New Delhi 1983 Thesis topic: British Orientalists and the History of Urdu Literature Topic: Jaafer Zatalli ke Kulliyaat ki M.Phil. JNU, New Delhi 1979 Tadween M.A. JNU, New Delhi 1977 Subjects: Urdu B.A. University of Allahabad 1972 Subjects: English Literature, Economics, Urdu Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Zakir Husain PG (E) College Lecturer 1983-98 Teaching and research University of Delhi Reader 1998 Teaching and research National Council for Promotion of Director April 2007 to Chief Executive Officer of the Council Urdu Language, HRD, New Delhi December ’08 Research Interests / Specialization Research interests: Literary criticism and literary historiography Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) (a) Post-graduate: 1. History of Urdu Literature 2. Poetry: Ghalib, Josh, Firaq Majaz, Nasir Kazmi 3. Prose: Ratan Nath Sarshar, Mohammed Husain Azad, Sir Syed (b) M. Phil: Literary Criticism Honors & Awards www.du.ac.in Page 1 a. Career Awardee of the UGC (1993). Completed a research project entitled “Impact of Delhi College on the Cultural Life of 19th Century” under the said scheme. -

Modernism and the Progressive Movement in Urdu Literature

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 2 No. 3; March 2012 Modernism and the Progressive Movement in Urdu Literature Sobia Kiran Asst. Professor English Department LCWU, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract The paper aims at exploring salient features of Progressive Movement in Urdu literature and taking into account points of comparison with Modernism in Europe. The paper explores evolution of Progressive Movement over the years and traces influence of European Modernism on it. Thesis statement: The Progressive Movement in Urdu literature was tremendously influenced by European Modernism. 1. Modernism The term Modernism is used to distinguish the literature that developed out of the First World War. Modernism deliberately broke with Western traditions of certainty. It came into being as they were collapsing. It challenged all the old modes. Important precursors of Modernism were Nietzsche, Freud and Marx who in different degrees rejected certainties in religion, philosophy, psychology and politics. They came to distrust the stability and order offered in earlier literary works. It broke with literary conventions. Like any new movement it rebelled against the old. It was nihilistic and tended to believe in its own self sufficiency. “Readers were now asked to look into themselves, to establish their real connections with the world and to ignore the rules of religion and society. Modernism wants therefore to break the old connections, because it believes that these are artificial and exploitative…” (Smith, P.xxi) The people are provoked to think and decide for themselves. They are expected to reconstruct their moralities. The concern for social welfare continued. “Every period has its dominant religion and hope…and “socialism” in a vague and undefined sense was the hope of the early twentieth century.”(Smith xiii) Marxism suffered an eclipse after the Second World War. -

Recruitment.Guru in Case of Any Guidance/Information/Clarification Regarding Their Applications, Candidature Etc

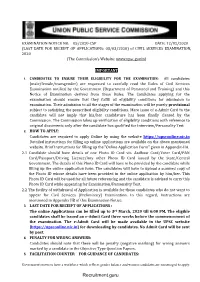

EXAMINATION NOTICE NO. 05/2020-CSP DATE: 12/02/2020 (LAST DATE FOR RECEIPT OF APPLICATIONS: 03/03/2020) of CIVIL SERVICES EXAMINATION, 2020 (The Commission’s Website: www.upsc.gov.in) IMPORTANT 1. CANDIDATES TO ENSURE THEIR ELIGIBILITY FOR THE EXAMINATION: All candidates (male/female/transgender) are requested to carefully read the Rules of Civil Services Examination notified by the Government (Department of Personnel and Training) and this Notice of Examination derived from these Rules. The Candidates applying for the examination should ensure that they fulfill all eligibility conditions for admission to examination. Their admission to all the stages of the examination will be purely provisional subject to satisfying the prescribed eligibility conditions. Mere issue of e-Admit Card to the candidate will not imply that his/her candidature has been finally cleared by the Commission. The Commission takes up verification of eligibility conditions with reference to original documents only after the candidate has qualified for Interview/Personality Test. 2. HOW TO APPLY: Candidates are required to apply Online by using the website https://upsconline.nic.in Detailed instructions for filling up online applications are available on the above mentioned website. Brief Instructions for filling up the "Online Application Form" given in Appendix-IIA. 2.1 Candidate should have details of one Photo ID Card viz. Aadhaar Card/Voter Card/PAN Card/Passport/Driving Licence/Any other Photo ID Card issued by the State/Central Government. The details of this Photo ID Card will have to be provided by the candidate while filling up the online application form. The candidates will have to upload a scanned copy of the Photo ID whose details have been provided in the online application by him/her. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Cat No 1 Junior Engineer (Civil)

List of Candidate’s whose fee is confirmed Note: The candidate who has deposited the fee in the designated bank and his/her name is not in the list are requested to either mail the fee deposit proof (i.e. fee challan) on [email protected] or contact personally with proof of fee deposit at CDAC-Mohali Office (A-34, phase VIII, Industrial Area, Mohali) on or before 18/09/2013 upto 5 pm. Post Name : Cat No 1 Junior Engineer (Civil) DoB Reg No Name Fathers Name Category 05/04/1990 30100003 mayank kumar sharma radhey shyam sharma General 01/11/1970 30100004 AJWANT SINGH GURTEJ SINGH SBC 02/02/1986 30100005 RAVINDRA KUMAR MOOL CHAND General 02/07/1991 30100010 KRISHAN KUMAR JASWANT SINGH BCA 07/11/1993 30100012 Sahil malhan Sunil malhan General 11/07/1995 30100015 SANJAY KUMAR RAM ASREY General 11/09/1993 30100017 MOHIT ASHOK KUMAR General 02/02/1986 30100020 RAVINDRA KUMAR MOOL CHAND General 01/10/1992 30100022 NAVNEET SINGH SATBIR SINGH General 12/12/1993 30100027 Lakshay budhiraja praveen budhiraja General 07/01/1993 30100029 RAKESH KUMAR DHARAM CHAND SC 01/09/1994 30100030 geetanshu naresh mukhija General 09/12/1995 30100033 KULWINDER KUMAR JASMER SINGH BCA 05/03/1992 30100034 MEENA RANI SATPAL SC 04/07/1991 30100036 JAGMOHAN SINGH SHIVNATH SINGH General 04/03/1991 30100037 BISHAL MAURYA NAND KISHOR MAURYA General 04/09/1989 30100042 SANDEEP RAJ PAL SC 10/02/1991 30100044 GAURAV SHARMA BRIJ BHUSHAN General 10/09/1991 30100045 PARAS MANI VOHRA JANKA RAJ VOHRA General List of Candidate’s whose fee is confirmed Note: The candidate who has deposited the fee in the designated bank and his/her name is not in the list are requested to either mail the fee deposit proof (i.e. -

1 CM Naim a Sentimental Essay in Three Scenes My Essay Has an Epigraph

C. M. Naim A Sentimental Essay in Three Scenes My essay has an epigraph; it comes, with due apologies and gratitude, from the bard of St. Louis, Mo., and gives, I hope, my ramblings a structure. No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be; Am an attendant lord, and Urdu-wala one that will do To swell a progress, start a scene or two Or, as in the case here, Exactly three Scene 1 In December 1906, twenty-eight men traveled to Dhaka to represent U.P. at the formation of the All India Muslim League. Two were from Bara Banki, one of them my granduncle, Raja Naushad Ali Khan of Mailaraigunj. Thirty-nine years later, during the winter of 1945-46, I could be seen marching up and down the only main road of Bara Banki with other kids, waving a Muslim League flag and shouting slogans. No, I don’t imply some unbroken trajectory from my granduncle’s trip to my strutting in the street, for the elections in 1945 were in fact based on principles that my granduncle reportedly opposed. It was Uncle Fareed who first informed me that Naushad Ali Khan had gone to Dhaka. Uncle Fareed knew the family lore, and enjoyed sharing it with us boys. In an aunt’s house I came across a fading picture. Seated in a dogcart and dressed in Western clothes and a jaunty hat, he looked like a slightly rotund and mustached English squire. He had 1 been a poet, and one of his couplets was then well known even outside the family. -

Scanned Using Scannx OS16000 PC

/' \ / / SAGAR 2017-2018 CHIEF EDITORS Sundas Amer, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Charlotte Giles, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Paromita Pain, Dept, of Journalism, UT Austin ^ EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE MEMBERS Nabeeha Chaudhary, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin Andrea Guiterrez, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Hamza Muhammad Iqbal, Comparative Literature, UT Austin Namrata Kanchan, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Kathleen Longwaters, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Daniel Ng, Anthropology, UT Austin Kathryn North, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Joshua Orme, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin David St. John, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Ramna Walia, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin WEB EDITOR Charlotte Giles & Paromita Pain PRINTDESIGNER Dana Johnson EDITORIAL ADVISORS Donald R. Davis, Jr., Director, UT South Asia Institute; Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Rachel S. Meyer, Assistant Director, UT South Asia Institute EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Barnett, Associate Professor, Dept, of History, University of Virginia Eric Lewis Beverley, Assistant Professor, Dept, of History, SUNY Stonybrook Purmma Bose, Associate Professor, Dept, of English, Indiana University-Bloomineton Laura Brueck, Assomate Professor, Asian Languages & Cultures Dept., Northwestern University Indrani Chatterjee, Dept, of History, UT-Austin uiuversiiy Lalitha Gopalan, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-TV-Film, UT-Austin Sumit Guha, Dept, of History, UT-Austin Kathryn Hansen, Professor Emerita, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Barbara Harlow, Professor, Dept, of English, UT-Austin Heather Hindman, Assistant Professor, Dept, of Anthropology, UT-Austin Syed Akbar Hyder, Associate Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Shanti Kumar, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-Television-Film, UT-Austin Janice Leoshko, Associate Professor, Dept, of Art and Art History, UT-Austin W. -

Report on Citizenship Law:Pakistan

CITIZENSHIP COUNTRY REPORT 2016/13 REPORT ON DECEMBER CITIZENSHIP 2016 LAW:PAKISTAN AUTHORED BY FARYAL NAZIR © Faryal Nazir, 2016 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Report on Citizenship Law: Pakistan RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2016/13 December 2016 © Faryal Nazir, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

The Maulana Who Loved Krishna

SPECIAL ARTICLE The Maulana Who Loved Krishna C M Naim This article reproduces, with English translations, the e was a true maverick. In 1908, when he was 20, he devotional poems written to the god Krishna by a published an anonymous article in his modest Urdu journal Urd -i-Mu’all (Aligarh) – circulation 500 – maulana who was an active participant in the cultural, H ū ā which severely criticised the British colonial policy in Egypt political and theological life of late colonial north India. regarding public education. The Indian authorities promptly Through this, the article gives a glimpse of an Islamicate charged him with “sedition”, and demanded the disclosure of literary and spiritual world which revelled in syncretism the author’s name. He, however, took sole responsibility for what appeared in his journal and, consequently, spent a little with its surrounding Hindu worlds; and which is under over one year in rigorous imprisonment – held as a “C” class threat of obliteration, even as a memory, in the singular prisoner he had to hand-grind, jointly with another prisoner, world of globalised Islam of the 21st century. one maund (37.3 kgs) of corn every day. The authorities also confi scated his printing press and his lovingly put together library that contained many precious manuscripts. In 1920, when the fi rst Indian Communist Conference was held at Kanpur, he was one of the organising hosts and pre- sented the welcome address. Some believe that it was on that occasion he gave India the slogan Inqilāb Zindabād as the equivalent to the international war cry of radicals: “Vive la Revolution” (Long Live The Revolution).