Sevasadan and Nirmala"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Varanasi Destinasia Tour Itinerary Places Covered

Varanasi Destinasia TOUR ITINERARY PLACES COVERED:- LAMHI – SARNATH – RAMESHWAR – CHIRAIGAON - SARAIMOHANA Day 01: Varanasi After breakfast transfer to the airport to board the flight for Varanasi. On arrival at Varanasi airport meet our representative and transfer to the hotel. In the evening, we shall take you to the river ghat for evening aarti. Enjoy aarti darshan at the river ghat and get amazed with the rituals of lams and holy chants. Later, return to the hotel for an overnight stay. Day 02: Varanasi - Lamhi Village - Sarnath - Varanasi We start our day a little early with a cup of tea followed by a drive to river Ghat. Here we will be enjoying the boat cruise on the river Ganges to observe the way of life of pilgrims by over Ghats. The boat ride at sunrise will provide a spiritual glimpse of this holy city. Further, we will explore the few temples of Varanasi. Later, return to hotel for breakfast. After breakfast we will leave for an excursion to Sarnath and Lamhi village. Sarnath is situated 10 km east of Varanasi, is one of the Buddhism's major centers of India. After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha came to Sarnath where he gave his first sermon. Visit the deer park and the museum. Later, drive to Lamhi Village situated towards west to Sarnath. The Lamhi village is the birthplace of the renowned Hindi and Urdu writer Munshi Premchand. Munshi Premchand acclaimed as the greatest narrator of the sorrows, joy and aspirations of the Indian Peasantry. Born in 1880, his fame as a writer went beyond the seven seas. -

Abstract the Current Paper Is an Effort to Examine the Perspective of Munshi Premchand on Women and Gender Justice

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, {Bi-Monthly}, ISSN 2249-9598, Volume-08, Aug 2018 Special Issue Feminism and Gender Issues in Some Fictional Works of Munshi Premchand Farooq Ahmed Ph.D Research Scholar, Barkatullah University, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh India Abstract The current paper is an effort to examine the perspective of Munshi Premchand on women and gender justice. Premchand’s artistic efforts were strongly determined with this social obligation, which possibly found the best representation in the method in which he treated the troubles of women in his fiction. In contrast to the earlier custom which placed women within the strictures of romantic archives Premchand formulated a new image of women in the perspective of the changes taking place in Indian society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The apprehension with the problem of women in Premchand’s fiction can be largely described as an attempt to discover the various aspects of feminism and femininity and their drawbacks and weaknesses in the socio-cultural condition obtaining in India. The plan was not to suggest a specific resolution or substitute but to highlight the complications involved in the formation of an ideal condition for women. Even when a substitute was recommended there was significant uncertainty. What was significant in the numerous themes pertaining to women which shaped the concern of his fiction was the predicament faced by Indian women in the conventional society influenced by a strange culture. This paper is an effort to examine some of the issues arising out of Premchand’s treatment of this dilemma. KEYWORDS: Feminism, Gender Justice, Patriarchy, Child Marriage, Sexual Morality, Female Education, Dowry, Unmatched Marriage, Society, Nation, Idealist, Realist etc. -

Adaptation of Premchand's “Shatranj Ke Khilari” Into Film

ASIATIC, VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2014 Translation as Allegory: Adaptation of Premchand’s “Shatranj Ke Khilari” into Film Omendra Kumar Singh1 Govt. P.G. College, Dausa, Rajasthan, India Abstract Roman Jakobson‟s idea that adaptation is a kind of translation has been further expanded by functionalist theorists who claim that translation necessarily involves interpretation. Premised on this view, the present paper argues that the adaptation of Premchand‟s short story “Shatranj ke Khilari” into film of that name by Satyajit Ray is an allegorical interpretation. The idea of allegorical interpretation is based on that ultimate four-fold schema of interpretation which Dante suggests to his friend, Can Grande della Scala, for interpretation of his poem Divine Comedy. This interpretive scheme is suitable for interpreting contemporary reality with a little modification. As Walter Benjamin believes that a translation issues from the original – not so much from its life as from its after-life – it is argued here that in Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation Premchand‟s short story undergoes a living renewal and becomes a purposeful manifestation of its essence. The film not only depicts the social and political condition of Awadh during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah but also opens space for engaging with the contemporary political reality of India in 1977. Keywords Translation, adaptation, interpretation, allegory, film, mise-en-scene Translation at its broadest is understood as transference of meaning between different natural languages. However, functionalists expanded the concept of translation to include interpretation as its necessary form which postulates the production of a functionalist target text maintaining relationship with a given source text. -

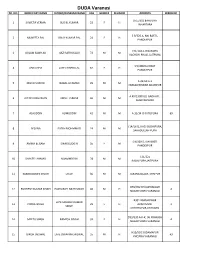

DUDA Varanasi SR

DUDA Varanasi SR. NO. BENIFICARY NAME FATHER/HUSBAND NAME AGE GENDER RELIGION ADDRESS WARD NO D 65/332 BAHULIYA 1 SHWETA VERMA SUSHIL KUMAR 23 F H LAHARTARA S 9/326 A, NAI BASTI , 2 MUNEETA PAL VINAY KUMAR PAL 24 F H PANDEYPUR J 31/118-1-B BANDHU 3 GULAM SABIR ALI HAZI SAFIRULLAH 72 M M KACHCHI BHAG, JAITPURA S 9/408 NAI BAST 4 USHA DEVI LATE CHHEDI LAL 62 F H PANDEYPUR A 33/60 A-1 5 MOHD SHAHID IKABAL AHAMAD 29 M M OMKALESHWAR ADAMPUR A 49/130DULLI GADHAYI , 6 ALTAPU REHAMAN ABDUL JABBAR 46 M M AMBIYAMANDI 7 ALAUDDIN ALIMUDDIN 42 M M A 32/34 CHHITUPURA 89 J 14/16 Q, KAGI SUDHIPURA, 8 AFSANA FATEH MOHMMAD 24 M M SAHADULLAH PURA S 9/369 D, NAI BASTI 9 AMINA BEGAM SIRAGGUDDIN 35 F M PANDEYPUR J 21/221 10 SHAKEEL AHMAD NIJAMMDDIN 28 M M RASALPURA,JAITPURA 11 KAMROODDIN SHEKH ESSUF 36 M M TARANA BAZAR, SHIVPUR D59/352 KH JAIPRAKASH 12 RUDRESH KUMAR SINGH PASHUPATI NATH SINGH 40 M H 4 NAGAR SIGRA VARANASI B301 BANSHIDHAR LATE SANJEEV KUMAR 13 POOJA SINGH 29 F H APARTMENT 2 SINGH CHHITTUPUR,VARANASI D59/330 A-K-K, JAI PRAKASH 14 MEETU SINGH RAMESH SINGH 33 F H 4 NAGAR SIGRA VARANASI N15/592 SUDAMAPUR 15 GIRISH JAISWAL LATE DWARIKA JAISWAL 55 M H 43 KHOJWA VARANASI N15/185 C BIRDOPUR BADI 16 NICKEY SINGH VISHAL SINGH 27 F H GAIBI VARANASI D59/330 AK-1K, JAI 17 PANKAJ PRATAP PRADEEP KUMAR ARYA 23 M H PRAKASH NAGAR SIGRA 4 VARANASI CV14/160 22 A2 18 SANDEEP RAJ KUMAR 29 M H GUJRATIGALI,SONIA 41 VARANASI C12/B LAHANGPURA SIGRA 19 PUSHPA DEVI VIJAY KUMAR 47 F H 41 VARANASI D51/82A-1 SURJAKUND 20 CHANDRASHEKHAR OMPRAKASH 41 M H 67 PURANA PAN DARIBA M15/107, SUDAMAPUR, 21 BHARAT GAUD GOPAL JI GAUD 30 M H KHOJAWAN, VARANASI Bhelupur Zone SR. -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion. -

Gold, Dust, Or Gold Dust Religion in the Life And

GOLD, DUST, OR GOLD DUST? RELIGION IN THE LIFE AND WRITINGS OF PREMCHAND Author(s): Arvind Sharma Source: Journal of South Asian Literature, Vol. 21, No. 2, ESSAYS ON PREMCHAND (Summer, Fall 1986), pp. 112-122 Published by: Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40874091 Accessed: 03-11-2019 20:36 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of South Asian Literature This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Sun, 03 Nov 2019 20:36:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Arvind Sharma GOLD, DUST, OR GOLD DUST? RELIGION IN THE LIFE AND WRITINGS OF PREMCHAND Was Premohand really an athiest? Premchand is regarded as one of the makers of modern Hindi literature and is known to his admirers as the 'king of novelists.1' The purpose of this paper is to examine the place of religion in his life and work. In order to carry out such an examination, however, some preliminary observations are necessary. First of all, the word 'religion' itself will need to be broadly interpre- ted in order to include those modern manifestations of religiosity which are more usually referred to as surrogates for religion, such as Marxism, humanism, nationalism, psychoanalysis, etc., apart from what are traditionally regarded as the religious traditions of mankind, such as Hinduism, etc. -

Representation of Indian Farmer Through the Eyes of Munshi Premchand

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 Received: 03-09-2019; Accepted: 07-10-2019 www.academicjournal.in Volume 4; Issue 6; November 2019; Page No. 47-50 Representation of Indian farmer through the eyes of Munshi Premchand Bhawna Teotia1, Dr. Geeta Gupta2 1 Research Scholar, Govt. Degree College, Kharkhoda, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India 2 Associate Professor, Govt. Degree College, Kharkhoda, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract Munshi Premchand was profoundly affected by the wretched conditions of Indian farmers and collaborated the life of farmers through his literature. Farmer, the backbone of Indian culture, has always been a strong link in the Indian economy. Being an agricultural country farmer played predominant role in the history of. Indian culture agriculture is not only the major part of Indian economy but also the part of Indian civilization. Munshi Premchand described the farmers of his time and the complications faced in their live. The farmers of his time lived a very dreadful life and also victims of injustice and exploitation of upper class. Landlord, moneylender, priest end police all were the main source of their exploitation. Farmers were always repressed by them and never get a chance to live with happiness and prosperity. The extent of their exploitation is even to be told that their crop used to balance in the field and they would stand empty handed. Keywords: farmer exploitation, repression, poverty Introduction marriage, exploitation of women, peasant and farmers, Indian Literature is incomplete without the greatest maltreatment of poor people and the unprivileged class. -

Bombay 100 Years Ago, Through the Eyes of Their Forefathers

Erstwhile, ‘Bombay’, 100 years ago was beautifully built by the British where the charm of its imagery and landscape was known to baffle all. The look and feel of the city was exclusively reserved for those who lived in that era and those who used to breathe an unassuming air which culminated to form the quintessential ‘old world charisma’. World Luxury Council (India) is showcasing, ‘never seen before’ Collectors’ Edition of 100 year old archival prints on canvas through a Vintage Art Exhibit. The beauty of the archival prints is that they are created with special ink which lasts for 100 years, thus not allowing the colors to fade. The idea is to elicit an unexplored era through paradoxically beautiful images of today’s maximum city and present it to an audience who would have only envisioned Bombay 100 years ago, through the eyes of their forefathers. The splendid collection would be an absolute treat for people to witness and make part of their ‘vintage art’ memorabilia. World Luxury Council India Headquartered in London, UK, World Luxury Council (India) is a ‘by invitation only’ organization which endeavours to provide strategic business opportunities and lifestyle management services though its 4 business verticals – World Luxury Council, World Luxury Club, Worldluxurylaunch.com and a publishing department for luxury magazines. This auxiliary marketing arm essentially caters to discerning corporate clients and high net worth individuals from the country and abroad. The Council works towards providing knowledge, assistance and advice to universal luxury brands, products and services requiring first class representation in Indian markets through a marketing mix of bespoke events, consultancy, web based promotions, distribution and networking platforms. -

Approaching the Question of Caste Subjugation In

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.4 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed Journal 2017 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE APPROACHING THE QUESTION OF CASTE SUBJUGATION IN PREMCHAND’S STORIES KAFAN AND SADGATI AND ANALYZING THEM WITH REFERENCE TO DOMINANT TRENDS NOTICED IN DALIT LITERATURE. Yashika Kant (Undergraduate Scholar,St Stephen’s College, Delhi University,Delhi.) Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of the paper is to explore the question of caste subjugation in the stories Kafan and Sadgati. The Indian society has been ridden with the menace of caste oppression since centuries. Premchand has been one of the foremost writers to undertake social issues in his writings. The purpose of writing this paper is to explore how caste hierarchy and oppression has been depicted in the works of Premchand and to critically analyse whether his two stories Kafan and Sadgati fall within the genre of ‘Dalit literature’. The paper deals extensively with the Dalit psyche and also the politics revolving around the concepts of purity and untouchability through the Dalit body. The significance of the paper lies in the fact that it enables one to analyse the representation of Dalits in literature by including the criticism of various writers against Premchand and decide for oneself how appropriate and extensive that representation has been. Keywords: Dalit, Death, Hierarchy, Women, Representation, Revolution. Citation: APA Kant,Y.(2017) Approaching the question of Caste Subjugation in Premchand’s Stories Kafan and Sadgati and analyzing them with reference to dominant trends noticed in Dalit Literature.Veda’s Journal of English Language and Literature-JOELL, 4(4), 187 - 193. -

Premchand and Language: on Translation, Cultural Nationalism

snehal shingavi Premchand and Language: On Translation, * Cultural Nationalism, and Irony ham kō bẖī kyā kyā mazē kī dāstānēñ yād tẖīñ lēkin ab tamhīd-e ẕikr-e dard-o-mātm hō gaʾīñ I, too, used to remember such wonderful tales of adventure But now all I can recollect has turned into painful dirges. órusva, Umrāʾō Jān Adā The epigraph to this essay is taken from the opening of Umrāʾō Jān Adā, Mirzā Muḥammad Hādī Rusvāís most famous novel, which begins with a lamentation on the prospects of storytelling in the present moment (the novel was published sometime between 1899 and 1905).1 The couplet ex- plains that what once was an archive of the pleasurable possibilities of fantastical fiction (mazē kī dāstānēñ) has now given way to the over- whelming immanence of dirges of pain and mourning (dard-o-mātam): it famously signals the shift that will take place at the end of the novel after the romantic escapades of the courtesan and her lover are brought to an abrupt end with the declining fortunes of the élite. The novel itself contains an almost innumerable number of such ghazal couplets strewn throughout the conversation between the eponymous courtesan and the author, all part of the elaborate pseudo-seduction that takes place between a now aged Umrāʾō Jān and the ever-flirtatious Rusvā. But opening the novel in this way is, in part, Rusvāís acknowledgement that the novel understands itself as straddling two traditions from the start, or more precisely, under- * This is a revised version of the paper presented at the International Seminar on Premchand in Translation, held at Jamia Millia, New Delhi, 28–30 November 2012. -

Shatranj Ke Khiladi’ Adaptation of Munshi Premchand’S ‘Shatranj Ki Baazi’

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com VOL: 10, No.: 1, SPRING 2020 REFREED, INDEXED, BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re- use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 48 | Cinematic Adaptation as ‘The Time Machine’ of Culture Cinematic Adaptation as ‘The Time Machine’ of Culture: A Brief Analysis of Satyajit Ray’s ‘Shatranj Ke Khiladi’ Adaptation of Munshi Premchand’s ‘Shatranj Ki Baazi’ Sumitra Dahiya Abstract: The aim of this paper is to throw the light on the emergence of cinematic adaptation of literature at present time. It also discusses the points related to the adaptation, its definition and codes of film adaptation. The paper gives the brief analysis of ‘Shatranj Ke Khiladi’ film and how it shows feudal Indian culture through visual presentation. It deals with the historical events and incidents of British Raj in India with strong evidences and documents. Key Words: Feudal, Luxury, Chess, Battle and Culture. *** Introduction: Culture dwells in the behaviour of people, their way of living, their manner of communication, their art, their music and their stories.