Premchand and Language: on Translation, Cultural Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Sevasadan and Nirmala"

Int.J.Eng.Lang.Lit&Trans.StudiesINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, Vol. LITERATURE3.Issue. 1.2016 (Jan-Mar) AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in KY PUBLICATIONS REVIEW ARTICLE Vol. 3. Issue 1.,2016 (Jan-Mar. ) SPACE AND PERSONHOOD IN PREMCHAND’S "SEVASADAN AND NIRMALA" SNEHA SHARMA Delhi University [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this essay is to examine city architecture and spaces within home in two of Premchand’s novels in an attempt to contextualize certain processes in self- fashioning and production of subjectivities. Every society has prevalent ways of structuring, producing, and conceptualizing space that reflect its dominant ideologies and social order. In other words, spaces are a reflection of social reality. Both these novels document these changing spaces marked by a period of accelerated change. Both these novels, Sevasadan and Nirmala, in the process of narrating the “private in public”, reveal a world shaped by a spatial economy which combines the social relations of reproduction with the relations of production. A knowledge of the spatio- temporal matrix which the characters inhabit, reveals the complex interrelation being formed between the exterior and the interior in a world in the first throes of modernity. The genre of the novel too, as a new form, offers an ideologically charged space, for the author to represent a world experiencing the formation of new socio- geographical settings. KEY WORDS: Modernity, social space, personhood ©KY PUBLICATIONS (Social) space is not a thing among other things, nor a product among other products: rather, it subsumes things produced, and encompasses their interrelationships in their coexistence and simultaneity – their (relative) order and/or (relative) disorder. -

Varanasi Destinasia Tour Itinerary Places Covered

Varanasi Destinasia TOUR ITINERARY PLACES COVERED:- LAMHI – SARNATH – RAMESHWAR – CHIRAIGAON - SARAIMOHANA Day 01: Varanasi After breakfast transfer to the airport to board the flight for Varanasi. On arrival at Varanasi airport meet our representative and transfer to the hotel. In the evening, we shall take you to the river ghat for evening aarti. Enjoy aarti darshan at the river ghat and get amazed with the rituals of lams and holy chants. Later, return to the hotel for an overnight stay. Day 02: Varanasi - Lamhi Village - Sarnath - Varanasi We start our day a little early with a cup of tea followed by a drive to river Ghat. Here we will be enjoying the boat cruise on the river Ganges to observe the way of life of pilgrims by over Ghats. The boat ride at sunrise will provide a spiritual glimpse of this holy city. Further, we will explore the few temples of Varanasi. Later, return to hotel for breakfast. After breakfast we will leave for an excursion to Sarnath and Lamhi village. Sarnath is situated 10 km east of Varanasi, is one of the Buddhism's major centers of India. After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha came to Sarnath where he gave his first sermon. Visit the deer park and the museum. Later, drive to Lamhi Village situated towards west to Sarnath. The Lamhi village is the birthplace of the renowned Hindi and Urdu writer Munshi Premchand. Munshi Premchand acclaimed as the greatest narrator of the sorrows, joy and aspirations of the Indian Peasantry. Born in 1880, his fame as a writer went beyond the seven seas. -

Abstract the Current Paper Is an Effort to Examine the Perspective of Munshi Premchand on Women and Gender Justice

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, {Bi-Monthly}, ISSN 2249-9598, Volume-08, Aug 2018 Special Issue Feminism and Gender Issues in Some Fictional Works of Munshi Premchand Farooq Ahmed Ph.D Research Scholar, Barkatullah University, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh India Abstract The current paper is an effort to examine the perspective of Munshi Premchand on women and gender justice. Premchand’s artistic efforts were strongly determined with this social obligation, which possibly found the best representation in the method in which he treated the troubles of women in his fiction. In contrast to the earlier custom which placed women within the strictures of romantic archives Premchand formulated a new image of women in the perspective of the changes taking place in Indian society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The apprehension with the problem of women in Premchand’s fiction can be largely described as an attempt to discover the various aspects of feminism and femininity and their drawbacks and weaknesses in the socio-cultural condition obtaining in India. The plan was not to suggest a specific resolution or substitute but to highlight the complications involved in the formation of an ideal condition for women. Even when a substitute was recommended there was significant uncertainty. What was significant in the numerous themes pertaining to women which shaped the concern of his fiction was the predicament faced by Indian women in the conventional society influenced by a strange culture. This paper is an effort to examine some of the issues arising out of Premchand’s treatment of this dilemma. KEYWORDS: Feminism, Gender Justice, Patriarchy, Child Marriage, Sexual Morality, Female Education, Dowry, Unmatched Marriage, Society, Nation, Idealist, Realist etc. -

Annual Return 2020 21.Pdf

KIRI INDUSTRIES LIMITED List of Shareholders As on 31.03.2021 SL FOLIO_DP_ NAME TOTAL_SHAR NO. CL_ID ES CLASS OF SHARES 1 12081800 09066984 . ANIL 15 EQUITY SHARE 2 11000011 00019887 5PAISA CAPITAL LIMITED 125 EQUITY SHARE 3 12082500 03171069 5PAISA CAPITAL LTD 2793 EQUITY SHARE 4 IN303028 74946126 A MURUGAN 100 EQUITY SHARE 5 IN302902 42346818 A POORNIMA 5 EQUITY SHARE 6 IN303028 50040956 A RAJARAMAN 902 EQUITY SHARE 7 IN301774 18813302 A AMUTHA 50 EQUITY SHARE 8 12036000 02203728 A ASHISHKUMAR . 610 EQUITY SHARE 9 12010900 11877367 A B KARTHIKEYAN . 1200 EQUITY SHARE 10 IN300513 14438886 A BABU 80 EQUITY SHARE 11 12010900 08363416 A BHAWESH KUMAR . 100 EQUITY SHARE 12 12010600 03190545 A CHAITANYA KUMAR 20 EQUITY SHARE 13 IN302269 13087726 A CHANDRAMOULEESWARAN 20 EQUITY SHARE 14 12030700 00437155 A G NARASIMHA RAO 20 EQUITY SHARE 15 IN301151 21799792 A ILANGOVAN 181 EQUITY SHARE 16 IN301356 20006929 A J SRINIVAS 9 EQUITY SHARE 17 12044700 07712603 A J YEGNESWARAN 40 EQUITY SHARE 18 IN302822 10395232 A K G SECURITIES AND CONSULTANCY LIMITED 1514 EQUITY SHARE 19 IN304295 20975809 A K VERMA 49 EQUITY SHARE 20 IN300888 13338342 A KIRAN SHETTY 100 EQUITY SHARE 21 IN301022 20825684 A KISHORE KUMAR 75 EQUITY SHARE 22 12044700 06612208 A M HONDAPPANAVAR 50 EQUITY SHARE 23 12044700 01194723 A MASTANAMMA 10 EQUITY SHARE 24 IN301151 25540407 A N J SHEIK ABDULLA 50 EQUITY SHARE 25 12076500 00121522 A NAGARATHNA 15 EQUITY SHARE 26 IN300669 10223530 A NARENDER REDDY 670 EQUITY SHARE 27 IN303077 10774003 A PADMAVATHY 50 EQUITY SHARE 28 12048800 00163502 A PL A ANNAMALAI CHETTIAR 50 EQUITY SHARE 29 IN301135 26465330 A PRANAVA 160 EQUITY SHARE 30 12010900 05675538 A PRIYA . -

Hasit Cv 21.2.14.PMD

Resume of Hasit Mehta Personal Details Name – Hasit Mehta Address – 'MAST',8, Chandralok Soc., Civil hosp. road, Nadiad 387001, Dist Kaira, Gujarat Phone – 9825780889 Email – [email protected] Objective To join world class educational institution in a challenging and rewarding. role with options of development and continual learning Professional Excellence Summary Over twenty two years experience in teaching at college level. Over Five years experience in College Administration Expertise in the field of education counselor at Various Institute. Expertise in the field of Gujarati literature, criticism and research. Conducted various adequate classes on the Literature and management. Have known well as an author, teacher, lecturer along with as a debater. Implemented various methods to develop relations between the students, teaching and administrative staff. Summary of skills: Ability to conduct lectures, workshops, and seminars Good knowledge of language & Literature. Ability to convey the concepts and theories of Literature to the students Ability to provide guidance to the students in their research projects Ability to perform managerial functions and administrative tasks. Ability to teach and train graduate and post graduate students Excellent communication skills and organizational ability Education SEPTEMBER 2002 PhD S.P. University, V.V.Nagar MAY 1992 M.A. 1st Class, M.S.Uni. Vadodara APRIL 1990 B.A. (1ST in Center) C.B.Patel Arts Col, Nadiad (Guj.Uni.) [1] Achievements • 05 books Authored • 07 Editorship • 06 under publication • 07 Reviewer ship of Research journals: • 44 research,criticism& review articles. • 09 researches with different institutions. • 37 seminars and workshops Participated • 18 seminars and worships Organized • 15 Honour. • 10 Citations in Print Media • 23 Art and Literary work • 27 Certificates About Achievements • 23 Different Level Exam Achievements • 59 lectures and presented papers at several levels • Referee Ph.D. -

Saurashtra University Library Service

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Etheses - A Saurashtra University Library Service Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Jadeja, Jaylaxmi M., 2007, “Feminist Concern in the Novels of Anita Desai and Varsha Adalja : A Study in Comparison”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/832 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author FEMINIST CONCERNS IN THE NOVELS OF ANITA DESAI AND VARSHA ADALJA: A STUDY IN COMPARISON DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY RAJKOT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH Supervised by: Submitted by: Dr. K. H. Mehta Jaylaxmi M. Jadeja Professor and Head, Lecturer, Smt. S. H. Gardi Institute of Matushri Virbaima English and Comparative Mahila Arts College, Literary Studies, Rajkot (Gujarat ) Saurashtra University, Rajkot (Gujarat) 2007 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that this dissertation on FEMINIST CONCERNS IN THE NOVELS OF ANITA DESAI AND VARSHA ADALJA: A STUDY IN COMPARISON is submitted by Ms. -

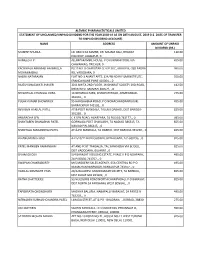

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

231036-Kalapi Text.Pdf

KALAPI The sculpture reproduced on the endpaper depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Suddhodana the dream of Queen Maya, mother of Lord Buddha. Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. This is perhaps the earliest available pictorial record of the art of writing in India. From Nagstjunakonda, 2nd centliry A. D. Coiatay : National Museum, New Delhi. MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE KALAPI HEMANTG.DESAI SAHTTYA AKADEMI 1. INTRODUCTION Gujarati literature is fortunate to have a good number of great poets. Kalapi, who flourished In “Pandit Yug" the literary period of scholar-writers is one of the noteworthy poets of modern Gujarati literature. In the annals of Indian literature he may not perhaps be recorded as a great poet but he is certainly a good poet; especially owing to the genuineness of feelings and simplicity of expression. Kalapi’s poetry has immediate effect upon its readers. Hisfavourite subjects are nature and love, both being the eternal subjects of poetry. Kalapi wrote some prose too. During a brief life of just 26 years, hewrotea lot and almost all his works have literary qualities. Besides poetry, he v/rote letters, dialogues, travelogues, etc. and all have creativity in them. He was considered a poet of the youth. He appealed to many young men and women and inspired them to write. Poetry always appeals to the lover of beauty and Kalapi's poetry makes' the reader a lover of poetry too. Kant, an eminent contemporary poet, has truly said of him: “Kalapi has nurtured the heart of Gujarat." This popularity as a poet has given longer life to his poetry but it has proved harmful too. -

Adaptation of Premchand's “Shatranj Ke Khilari” Into Film

ASIATIC, VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2014 Translation as Allegory: Adaptation of Premchand’s “Shatranj Ke Khilari” into Film Omendra Kumar Singh1 Govt. P.G. College, Dausa, Rajasthan, India Abstract Roman Jakobson‟s idea that adaptation is a kind of translation has been further expanded by functionalist theorists who claim that translation necessarily involves interpretation. Premised on this view, the present paper argues that the adaptation of Premchand‟s short story “Shatranj ke Khilari” into film of that name by Satyajit Ray is an allegorical interpretation. The idea of allegorical interpretation is based on that ultimate four-fold schema of interpretation which Dante suggests to his friend, Can Grande della Scala, for interpretation of his poem Divine Comedy. This interpretive scheme is suitable for interpreting contemporary reality with a little modification. As Walter Benjamin believes that a translation issues from the original – not so much from its life as from its after-life – it is argued here that in Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation Premchand‟s short story undergoes a living renewal and becomes a purposeful manifestation of its essence. The film not only depicts the social and political condition of Awadh during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah but also opens space for engaging with the contemporary political reality of India in 1977. Keywords Translation, adaptation, interpretation, allegory, film, mise-en-scene Translation at its broadest is understood as transference of meaning between different natural languages. However, functionalists expanded the concept of translation to include interpretation as its necessary form which postulates the production of a functionalist target text maintaining relationship with a given source text. -

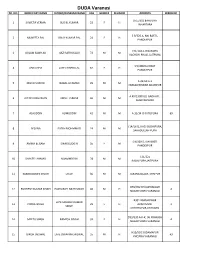

DUDA Varanasi SR

DUDA Varanasi SR. NO. BENIFICARY NAME FATHER/HUSBAND NAME AGE GENDER RELIGION ADDRESS WARD NO D 65/332 BAHULIYA 1 SHWETA VERMA SUSHIL KUMAR 23 F H LAHARTARA S 9/326 A, NAI BASTI , 2 MUNEETA PAL VINAY KUMAR PAL 24 F H PANDEYPUR J 31/118-1-B BANDHU 3 GULAM SABIR ALI HAZI SAFIRULLAH 72 M M KACHCHI BHAG, JAITPURA S 9/408 NAI BAST 4 USHA DEVI LATE CHHEDI LAL 62 F H PANDEYPUR A 33/60 A-1 5 MOHD SHAHID IKABAL AHAMAD 29 M M OMKALESHWAR ADAMPUR A 49/130DULLI GADHAYI , 6 ALTAPU REHAMAN ABDUL JABBAR 46 M M AMBIYAMANDI 7 ALAUDDIN ALIMUDDIN 42 M M A 32/34 CHHITUPURA 89 J 14/16 Q, KAGI SUDHIPURA, 8 AFSANA FATEH MOHMMAD 24 M M SAHADULLAH PURA S 9/369 D, NAI BASTI 9 AMINA BEGAM SIRAGGUDDIN 35 F M PANDEYPUR J 21/221 10 SHAKEEL AHMAD NIJAMMDDIN 28 M M RASALPURA,JAITPURA 11 KAMROODDIN SHEKH ESSUF 36 M M TARANA BAZAR, SHIVPUR D59/352 KH JAIPRAKASH 12 RUDRESH KUMAR SINGH PASHUPATI NATH SINGH 40 M H 4 NAGAR SIGRA VARANASI B301 BANSHIDHAR LATE SANJEEV KUMAR 13 POOJA SINGH 29 F H APARTMENT 2 SINGH CHHITTUPUR,VARANASI D59/330 A-K-K, JAI PRAKASH 14 MEETU SINGH RAMESH SINGH 33 F H 4 NAGAR SIGRA VARANASI N15/592 SUDAMAPUR 15 GIRISH JAISWAL LATE DWARIKA JAISWAL 55 M H 43 KHOJWA VARANASI N15/185 C BIRDOPUR BADI 16 NICKEY SINGH VISHAL SINGH 27 F H GAIBI VARANASI D59/330 AK-1K, JAI 17 PANKAJ PRATAP PRADEEP KUMAR ARYA 23 M H PRAKASH NAGAR SIGRA 4 VARANASI CV14/160 22 A2 18 SANDEEP RAJ KUMAR 29 M H GUJRATIGALI,SONIA 41 VARANASI C12/B LAHANGPURA SIGRA 19 PUSHPA DEVI VIJAY KUMAR 47 F H 41 VARANASI D51/82A-1 SURJAKUND 20 CHANDRASHEKHAR OMPRAKASH 41 M H 67 PURANA PAN DARIBA M15/107, SUDAMAPUR, 21 BHARAT GAUD GOPAL JI GAUD 30 M H KHOJAWAN, VARANASI Bhelupur Zone SR. -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion.