Download (4Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answered On:30.04.2002 Deletion of Parts from History Text Books T

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:5373 ANSWERED ON:30.04.2002 DELETION OF PARTS FROM HISTORY TEXT BOOKS T. GOVINDAN Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government are aware that CBSE had written tos chools ascertaining them to delete some sections from several history text books; and (b) if so, the details thereof; Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (PROF. RITA VERMA) (a) & (b) : Yes, Sir. Based on the recommendations made by National Council of Educational Research and Training, the Central Board of Secondary Education had directed its affiliated schools not to teach or set any question from certain portions from NCERT history text books during the session 2001-2002. The details of the parts deleted are as below: - Class VI - Ancient India- Romila Thapar - In fact- as a punishment-Life in the Vedic Age - p.p.40-41 Class VIII - Modern India - Arjun Dev and Indira Arjun Dev - Another power. Intrigues at Delhi - India in the Eighteenth Century - p.p.21 Class XI- Ancient India-Ram Sharan Sharma - To the second. Societies of EuropeModern Historians of Ancient India p.p.7 - Archaeological evidence in the present chapter-Types of Sources and Historical construction p.p.20-21 - The people living. nearly four hectares-Chalcolithic Farming Culture p.p.45 - The Cattle Vedic sacrifices Jainism and Budhism p.p.90 - Vardhman Mahavira and Jainism:According to Jainas in 527 BC Jainism and Budhism p.p.91-92 - Brahmanical Reaction: The brahmanical reaction…nelglected by Ashoka Significance of the Maurya Rule-p.p.137-138 - The Varna System: Religion influenced brahmanical indoctrination and the Varna System Legacy in Science and Civilization p.p.240-241 Class XI - Medieval India Satish Chandra The Sikhs: Although there regional independence Climax and Disintegration of the Mughal Empire p.p.237-238. -

PAST CULTURES AS the HERITAGE of the PRESENT Romila Thapar

1 Keynote lecture delivered at SOAS South Asia Institute/Presidency University conference on ‘Heritage and History in South Asia’, celebrating the centenary of SOAS University of London. Monday 5 September 2016 PAST CULTURES AS THE HERITAGE OF THE PRESENT Romila Thapar Heritage as we all know, is that which is inherited and can refer to objects, ideas or practices. It was once assumed that heritage is what has been handed down to us by our ancestors, neatly packaged, and which we pass on to our descendants, still neatly packaged. Now we know that much repackaging is done and some contents changed, but it still continues to be thought of as ancestral. This is because it has become central to identity and to its legitimation. Heritage is often associated with tradition. Whereas heritage is thought of as rather static, tradition is a more active transmission. Hence it moulds our lives more closely. Between them they are viewed as the still point of a turning world, except that this is a myth, since they too turn and are not still. We prefer to think that these have been passed down relatively unchanged. However, they mutate slowly in an evolving process that makes the mutation less discernable. But the more we seek to understand them the more we realize that each generation changes their content or their meaning, sometimes marginally but often more substantially. The unchanged label gives it a seeming continuity. More recently it has been argued that both heritage and tradition are the inter- play between what we believe existed in the past and our aspirations of the present. -

Early India: from the Origins to AD 1300

RESOURCES ESSAY BOOK REVIEW tial in the understanding of Early India Indian society. All are repre- sented by scholars of great From the Origins to AD 1300 learning, who were dedicated to the modern historical BY ROMILA THAPAR method that had become part BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, of the world of scholarship in 2002 India as elsewhere, and they are given judicious examina- 556 PAGES PLUS PREFACE tion in a chapter Thapar calls ILLUSTRATIONS, FIGURES, MAPS, CHRONOLOGY, GLOSSARY, “perceptions of the past.” BIBLIOGRAPHIES, AND INDEX The first of these trends is ISBN 0-520-23899-CLOTH often referred to as “imperial- ist.” It was largely the product of writers connected with British rule in India and was he importance of Romila Thapar’s achievement in Early also basically concerned with India: From the Origins to 1300 AD, in relation to the work the fate of empires in the Indi- T of her predecessors, lies in her access to new archaeological an subcontinent. One of the and literary sources, which she herself did not have when she wrote a earliest and probably the most influential of such historians was shorter version forty years ago, as well as in her understanding of the Vincent Smith, whose Early History of India was first published in nature of the enterprise of writing history. Spelled out in an introduc- 1904, was republished as late as 1957, and was widely used as a text tion, this understanding is the essential background for following in both India and the West. For Smith, the key to understanding Indi- Thapar’s approach. -

Annual Return 2020 21.Pdf

KIRI INDUSTRIES LIMITED List of Shareholders As on 31.03.2021 SL FOLIO_DP_ NAME TOTAL_SHAR NO. CL_ID ES CLASS OF SHARES 1 12081800 09066984 . ANIL 15 EQUITY SHARE 2 11000011 00019887 5PAISA CAPITAL LIMITED 125 EQUITY SHARE 3 12082500 03171069 5PAISA CAPITAL LTD 2793 EQUITY SHARE 4 IN303028 74946126 A MURUGAN 100 EQUITY SHARE 5 IN302902 42346818 A POORNIMA 5 EQUITY SHARE 6 IN303028 50040956 A RAJARAMAN 902 EQUITY SHARE 7 IN301774 18813302 A AMUTHA 50 EQUITY SHARE 8 12036000 02203728 A ASHISHKUMAR . 610 EQUITY SHARE 9 12010900 11877367 A B KARTHIKEYAN . 1200 EQUITY SHARE 10 IN300513 14438886 A BABU 80 EQUITY SHARE 11 12010900 08363416 A BHAWESH KUMAR . 100 EQUITY SHARE 12 12010600 03190545 A CHAITANYA KUMAR 20 EQUITY SHARE 13 IN302269 13087726 A CHANDRAMOULEESWARAN 20 EQUITY SHARE 14 12030700 00437155 A G NARASIMHA RAO 20 EQUITY SHARE 15 IN301151 21799792 A ILANGOVAN 181 EQUITY SHARE 16 IN301356 20006929 A J SRINIVAS 9 EQUITY SHARE 17 12044700 07712603 A J YEGNESWARAN 40 EQUITY SHARE 18 IN302822 10395232 A K G SECURITIES AND CONSULTANCY LIMITED 1514 EQUITY SHARE 19 IN304295 20975809 A K VERMA 49 EQUITY SHARE 20 IN300888 13338342 A KIRAN SHETTY 100 EQUITY SHARE 21 IN301022 20825684 A KISHORE KUMAR 75 EQUITY SHARE 22 12044700 06612208 A M HONDAPPANAVAR 50 EQUITY SHARE 23 12044700 01194723 A MASTANAMMA 10 EQUITY SHARE 24 IN301151 25540407 A N J SHEIK ABDULLA 50 EQUITY SHARE 25 12076500 00121522 A NAGARATHNA 15 EQUITY SHARE 26 IN300669 10223530 A NARENDER REDDY 670 EQUITY SHARE 27 IN303077 10774003 A PADMAVATHY 50 EQUITY SHARE 28 12048800 00163502 A PL A ANNAMALAI CHETTIAR 50 EQUITY SHARE 29 IN301135 26465330 A PRANAVA 160 EQUITY SHARE 30 12010900 05675538 A PRIYA . -

Hasit Cv 21.2.14.PMD

Resume of Hasit Mehta Personal Details Name – Hasit Mehta Address – 'MAST',8, Chandralok Soc., Civil hosp. road, Nadiad 387001, Dist Kaira, Gujarat Phone – 9825780889 Email – [email protected] Objective To join world class educational institution in a challenging and rewarding. role with options of development and continual learning Professional Excellence Summary Over twenty two years experience in teaching at college level. Over Five years experience in College Administration Expertise in the field of education counselor at Various Institute. Expertise in the field of Gujarati literature, criticism and research. Conducted various adequate classes on the Literature and management. Have known well as an author, teacher, lecturer along with as a debater. Implemented various methods to develop relations between the students, teaching and administrative staff. Summary of skills: Ability to conduct lectures, workshops, and seminars Good knowledge of language & Literature. Ability to convey the concepts and theories of Literature to the students Ability to provide guidance to the students in their research projects Ability to perform managerial functions and administrative tasks. Ability to teach and train graduate and post graduate students Excellent communication skills and organizational ability Education SEPTEMBER 2002 PhD S.P. University, V.V.Nagar MAY 1992 M.A. 1st Class, M.S.Uni. Vadodara APRIL 1990 B.A. (1ST in Center) C.B.Patel Arts Col, Nadiad (Guj.Uni.) [1] Achievements • 05 books Authored • 07 Editorship • 06 under publication • 07 Reviewer ship of Research journals: • 44 research,criticism& review articles. • 09 researches with different institutions. • 37 seminars and workshops Participated • 18 seminars and worships Organized • 15 Honour. • 10 Citations in Print Media • 23 Art and Literary work • 27 Certificates About Achievements • 23 Different Level Exam Achievements • 59 lectures and presented papers at several levels • Referee Ph.D. -

Saurashtra University Library Service

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Etheses - A Saurashtra University Library Service Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Jadeja, Jaylaxmi M., 2007, “Feminist Concern in the Novels of Anita Desai and Varsha Adalja : A Study in Comparison”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/832 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author FEMINIST CONCERNS IN THE NOVELS OF ANITA DESAI AND VARSHA ADALJA: A STUDY IN COMPARISON DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY RAJKOT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH Supervised by: Submitted by: Dr. K. H. Mehta Jaylaxmi M. Jadeja Professor and Head, Lecturer, Smt. S. H. Gardi Institute of Matushri Virbaima English and Comparative Mahila Arts College, Literary Studies, Rajkot (Gujarat ) Saurashtra University, Rajkot (Gujarat) 2007 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that this dissertation on FEMINIST CONCERNS IN THE NOVELS OF ANITA DESAI AND VARSHA ADALJA: A STUDY IN COMPARISON is submitted by Ms. -

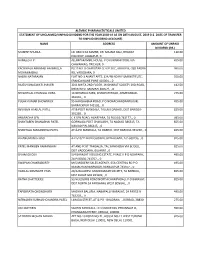

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

Occasional Paper No. 159 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK from the AYODHYA DEBATE TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA CENTRE for STUDIES I

Occasional Paper No. 159 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK FROM THE AYODHYA DEBATE TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES, CALCUTTA EH £>2&3 Occasional Paper No. 159 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK FROM THE AYODHYA DEBATE j ; vmm 12 AOS 1097 TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA APRIL 1997 CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES, CALCUTTA 10 Lake Terrace, Calcutta 700 029 1 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK FROM THE AYODHYA DEBATE Tapati Guha-Thakurta Archaeology in India hit the headlines with the Ayodhya controversy: no other discipline stands as centrally implicated in the crisis that has racked this temple town, and with it, the whole nation. The Ramjanmabhoomi movement, as we know, gained its entire logic and momentum from the claims to the prior existence of a Hindu temple at the precise site of the 16th century mosque that was erected by Babar. Myth and legend, faith and belief acquired the armour of historicity in ways that could present a series of conjectures as undisputed facts. So, the 'certainty' of present-day Ayodhya as the historical birthplace of Lord Rama passes into the 'certainty' of the presence of an lOth/llth century Vaishnava temple commemorating the birthplace site, both these in turn building up to the 'hard fact' of the demolition of this temple in the 16th century to make way for the Babri Masjid. Such invocation of'facts' made it imperative for a camp of left/liberal/secular historians to attack these certainties, to riddle them with doubts and counter-facts. What this has involved is a righteous recuperation of the fields of history and archaeology from their political misuse. -

Reexamining Secularism the Ayodhya Dispute and the Equal Treatment of Religions

journal of law, religion and state 5 (2017) 117-147 brill.com/jlrs Reexamining Secularism The Ayodhya Dispute and the Equal Treatment of Religions Geetanjali Srikantan* Assistant Professor of Global Legal History, Tilburg Law School [email protected] Abstract It is widely recognized that the secular Indian state unlike its Western counterpart does not follow the strict separation of religion and state, opting to intervene in the domain of religion by treating religions equally. This article examines how the concept of equal treatment of religions is applied in the legal domain by an intellectual history of the Ayodhya litigation and argues that the courts cannot treat religions equally due to the incompatible nature of the claims made by the parties i.e. the history of reli- gion claim of the Hindus vis-a-vis the property rights claim of the Muslims. Departing significantly from the current consensus about the litigation being characterized by defective legal interpretation and political influences, it further argues that the real le- gal challenge in resolving this dispute is addressing the theological frameworks within modern property law which are dependent on a set of normative inferences embed- ded in colonial discourse. * Acknowledgments: Versions of this paper have been presented at the symposium on “Unex- pected Sources of Law” held at the David Berg Foundation Institute for Law and History, Tel Aviv University, and the Conference on Religion and Equality held at Bar Ilan University. For inputs on this paper I am indebted to Ron Harris, David Schorr, Assaf Likhovski, Roy Kreit- ner, Lena Salaymeh, Levi Cooper and Ayelet Libson. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 5 | feBRUaRY - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE POLITICS OF ORIENTALISM AND OCCIDENTALISM Nitin Sharma M.A., NET (Political Science) ABSTRACT : This paper is about the concepts of Orientalism and Occidentalism and the politics, which revolve around these concepts in world, with a special emphasise, on India's contemporary scenario, which have its roots in history and its various interpretations. After this we will analyse how the concept of orientalism was used by the Britishers as a tool of exploration and for their hegemonic constructed ideology, and how it actually benefits the Britishers in India. The myth they created is primitive as compared to the prevailing advanced myth of India and the long traditions of liberal and pluralistic values, which prevailed in India. After which we will discuss about the Post-Modern concepts of Neo-orientalism. How the threat of clash of civilization is evolving there and how it can be overcome by a well furbished understanding of India's Indianess. This paper is slightly oriented towards the theoretical sphere as compare to the factual content but facts are provided where they are necessary. As Gopal Guru says that there are some "Theoretical Pundits" and some "Empirical Shudras" in India-while I tried to write this paper into a theoretical structure filled up with the empirical facts. KEYWORDS : Orientalism, Occidentalism, Myth, Post-secular. INTRODUCTION: Orientalism is a concept which is used by colonizers for their colonies for depicting these colonies as the countries in the east of the Mediterranean, usually referred to as Asia. -

231036-Kalapi Text.Pdf

KALAPI The sculpture reproduced on the endpaper depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Suddhodana the dream of Queen Maya, mother of Lord Buddha. Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. This is perhaps the earliest available pictorial record of the art of writing in India. From Nagstjunakonda, 2nd centliry A. D. Coiatay : National Museum, New Delhi. MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE KALAPI HEMANTG.DESAI SAHTTYA AKADEMI 1. INTRODUCTION Gujarati literature is fortunate to have a good number of great poets. Kalapi, who flourished In “Pandit Yug" the literary period of scholar-writers is one of the noteworthy poets of modern Gujarati literature. In the annals of Indian literature he may not perhaps be recorded as a great poet but he is certainly a good poet; especially owing to the genuineness of feelings and simplicity of expression. Kalapi’s poetry has immediate effect upon its readers. Hisfavourite subjects are nature and love, both being the eternal subjects of poetry. Kalapi wrote some prose too. During a brief life of just 26 years, hewrotea lot and almost all his works have literary qualities. Besides poetry, he v/rote letters, dialogues, travelogues, etc. and all have creativity in them. He was considered a poet of the youth. He appealed to many young men and women and inspired them to write. Poetry always appeals to the lover of beauty and Kalapi's poetry makes' the reader a lover of poetry too. Kant, an eminent contemporary poet, has truly said of him: “Kalapi has nurtured the heart of Gujarat." This popularity as a poet has given longer life to his poetry but it has proved harmful too. -

Saraswatichandra Story in Gujarati Language Pdf

Saraswatichandra Story In Gujarati Language Pdf This novel is based on the life of Jagga daku or rather its his life-story, which became one of the best-selling novels of Gujarati language. It first appeared. Varshik Val Kapavavano Divas (Annual Haircut Day-Gujarati) (વાિષક વાળ Publisher: Pratham Books, Book Type: pdf, Categories: Children, ISBN(13):. history of translation in the deep past because Gujarātī is not considered so old language as Saraswatichandra in four parts published between. 1887 and 1901 is (1876-1958) translated Ramesh Dutt's story “The. Lake of Sams”. Currently you are viewing the latest Copa America Schedule 2015 Pdf File about Copa America Schedule 2015 Pdf File Download Bd Time news and top stories. 2015 (afp) - hunkered down in his pakistani compound language books and varun news - mina raju story downlod gujarati - images of hamri aduri kahani. Ethnicity, Gujarati His second film was a triangular love story, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, starring It also was India's submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In 2013, Bhansali debuted in television with the show Saraswatichandra starring Jump up ^ "50th National Film Awards" (PDF). Free ebook download as PDF File (.pdf), Text file (.txt) or read book online for free. 2015 Pune become a part of the film fraternity and take their stories across the world. Marathi, the language of the state of Maharashtra. In a nation crippled with poverty and crime, young Saraswatichandra is brought up by his Saraswatichandra Story In Gujarati Language Pdf >>>CLICK HERE<<< Gammat Sathe Ganit-Samay Ane Nanan (Happy Maths 04-Gujarati) (ગમત Publisher: Pratham Books, Book Type: pdf, Categories: Children, ISBN(13):.