Premchand in the German Language: Paratexts and Translations*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

S. No TITLE AUTHOR 1 the GREAT INDIAN MIDDLE CLASS PAVAN K

JAWAHARLAL NEHRU INDIAN CULTURAL CENTRE EMBASSY OF INDIA JAKARTA JNICC JAKARTA LIBRARY BOOK LIST (PDF version) LARGEST COLLECTION OF INDIAN WRITINGS IN INDONESIA Simple way to find your favourite book ~ write the name of the Book / Author of your choice in “FIND” ~ Note it down & get it collected from the Library in charge of JNICC against your Library membership card. S. No TITLE AUTHOR 1 1 THE GREAT INDIAN MIDDLE CLASS PAVAN K. VERMA 2 THE GREAT INDIAN MIDDLE CLASS PAVAN K. VERMA 3 SOCIAL FORESTRY PLANTATIONS K.M. TIWARI & R.V. SINGH 4 INDIA'S CULTURE. THE STATE, THE ARTS AND BEYOND. B.P. SINGH 5 INDIA'S CULTURE. THE STATE, THE ARTS AND BEYOND. B.P. SINGH 6 INDIA'S CULTURE. THE STATE, THE ARTS AND BEYOND. B.P. SINGH UMA SHANKAR JHA & PREMLATA 7 INDIAN WOMEN TODAY VOL. 1 PUJARI 8 INDIA AND WORLD CULTURE V. K. GOKAK VIDYA NIVAS MISHRA AND RFAEL 9 FROM THE GANGES TO THE MEDITERRANEAN ARGULLOL 10 DISTRICT DIARY JASWANT SINGH 11 TIRANGA OUR NATIONAL - FLAG LT. Cdr.K. V. SINGH (Retd) 12 PAK PROXY WAR. A STORY OF ISI, BIN LADEN AND KARGIL RAJEEV SHARMA 13 THE RINGING RADIANCE SIR COLIN GARBETT S. BHATT & AKHTAR MAJEED 14 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND FEDERALISM (EDITOR) 15 KAUTILYA TODAY JAIRAM RAMESH VASUDHA DALMIA, ANGELIKA 16 CHARISMA & CANON MALINAR, MARTIN CHRISTOF (EDITOR) 17 A GOAN POTPOURRI ANIBAL DA COSTA 18 SOURCES OF INDIAN TRADITION VOL. 2 STEPHEN HAY (EDITOR) 19 SECURING INDIA'S FUTURE IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM BRAHMA CHELLANEY(EDITOR) 20 INDIA FROM MIDNIGHT TO THE MILLENNIUM SHASHI THAROOR 21 DOA (BHS INDONESIA) M. -

List of Documentaries Produced by Sahitya Akademi

LIST OF DOCUMENTARIES PRODUCED BY SAHITYA AKADEMI S.No.AuthorDirected byDuration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. ThakazhiSivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopala krishnaAdiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. VindaKarandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) DilipChitre 27 minutes 15. BhishamSahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. TarashankarBandhopadhyay(Bengali)Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. VijaydanDetha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. NavakantaBarua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. QurratulainHyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. Vijayan (Malayalam) K.M. Madhusudhanan 27 minutes 31. Syed Abdul Malik (Assamese) Dara Ahmed 27 minutes 32. -

Sevasadan and Nirmala"

Int.J.Eng.Lang.Lit&Trans.StudiesINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, Vol. LITERATURE3.Issue. 1.2016 (Jan-Mar) AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in KY PUBLICATIONS REVIEW ARTICLE Vol. 3. Issue 1.,2016 (Jan-Mar. ) SPACE AND PERSONHOOD IN PREMCHAND’S "SEVASADAN AND NIRMALA" SNEHA SHARMA Delhi University [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this essay is to examine city architecture and spaces within home in two of Premchand’s novels in an attempt to contextualize certain processes in self- fashioning and production of subjectivities. Every society has prevalent ways of structuring, producing, and conceptualizing space that reflect its dominant ideologies and social order. In other words, spaces are a reflection of social reality. Both these novels document these changing spaces marked by a period of accelerated change. Both these novels, Sevasadan and Nirmala, in the process of narrating the “private in public”, reveal a world shaped by a spatial economy which combines the social relations of reproduction with the relations of production. A knowledge of the spatio- temporal matrix which the characters inhabit, reveals the complex interrelation being formed between the exterior and the interior in a world in the first throes of modernity. The genre of the novel too, as a new form, offers an ideologically charged space, for the author to represent a world experiencing the formation of new socio- geographical settings. KEY WORDS: Modernity, social space, personhood ©KY PUBLICATIONS (Social) space is not a thing among other things, nor a product among other products: rather, it subsumes things produced, and encompasses their interrelationships in their coexistence and simultaneity – their (relative) order and/or (relative) disorder. -

Varanasi Destinasia Tour Itinerary Places Covered

Varanasi Destinasia TOUR ITINERARY PLACES COVERED:- LAMHI – SARNATH – RAMESHWAR – CHIRAIGAON - SARAIMOHANA Day 01: Varanasi After breakfast transfer to the airport to board the flight for Varanasi. On arrival at Varanasi airport meet our representative and transfer to the hotel. In the evening, we shall take you to the river ghat for evening aarti. Enjoy aarti darshan at the river ghat and get amazed with the rituals of lams and holy chants. Later, return to the hotel for an overnight stay. Day 02: Varanasi - Lamhi Village - Sarnath - Varanasi We start our day a little early with a cup of tea followed by a drive to river Ghat. Here we will be enjoying the boat cruise on the river Ganges to observe the way of life of pilgrims by over Ghats. The boat ride at sunrise will provide a spiritual glimpse of this holy city. Further, we will explore the few temples of Varanasi. Later, return to hotel for breakfast. After breakfast we will leave for an excursion to Sarnath and Lamhi village. Sarnath is situated 10 km east of Varanasi, is one of the Buddhism's major centers of India. After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha came to Sarnath where he gave his first sermon. Visit the deer park and the museum. Later, drive to Lamhi Village situated towards west to Sarnath. The Lamhi village is the birthplace of the renowned Hindi and Urdu writer Munshi Premchand. Munshi Premchand acclaimed as the greatest narrator of the sorrows, joy and aspirations of the Indian Peasantry. Born in 1880, his fame as a writer went beyond the seven seas. -

Abstract the Current Paper Is an Effort to Examine the Perspective of Munshi Premchand on Women and Gender Justice

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, {Bi-Monthly}, ISSN 2249-9598, Volume-08, Aug 2018 Special Issue Feminism and Gender Issues in Some Fictional Works of Munshi Premchand Farooq Ahmed Ph.D Research Scholar, Barkatullah University, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh India Abstract The current paper is an effort to examine the perspective of Munshi Premchand on women and gender justice. Premchand’s artistic efforts were strongly determined with this social obligation, which possibly found the best representation in the method in which he treated the troubles of women in his fiction. In contrast to the earlier custom which placed women within the strictures of romantic archives Premchand formulated a new image of women in the perspective of the changes taking place in Indian society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The apprehension with the problem of women in Premchand’s fiction can be largely described as an attempt to discover the various aspects of feminism and femininity and their drawbacks and weaknesses in the socio-cultural condition obtaining in India. The plan was not to suggest a specific resolution or substitute but to highlight the complications involved in the formation of an ideal condition for women. Even when a substitute was recommended there was significant uncertainty. What was significant in the numerous themes pertaining to women which shaped the concern of his fiction was the predicament faced by Indian women in the conventional society influenced by a strange culture. This paper is an effort to examine some of the issues arising out of Premchand’s treatment of this dilemma. KEYWORDS: Feminism, Gender Justice, Patriarchy, Child Marriage, Sexual Morality, Female Education, Dowry, Unmatched Marriage, Society, Nation, Idealist, Realist etc. -

Postmodern Traces and Recent Hindi Novels

Postmodern Traces and Recent Hindi Novels Veronica Ghirardi University of Turin, Italy Series in Literary Studies Copyright © 2021 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Literary Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020952110 ISBN: 978-1-62273-880-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by pch.vector / Freepik. To Alessandro & Gabriele If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough Albert Einstein Table of contents Foreword by Richard Delacy ix Language, Literature and the Global Marketplace: The Hindi Novel and Its Reception ix Acknowledgements xxvii Notes on Hindi terms and transliteration xxix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. -

Festival of Letters 2014

DELHI Festival of Letters 2014 Conglemeration of Writers Festival of Letters 2014 (Sahityotsav) was organised in Delhi on a grand scale from 10-15 March 2014 at a few venues, Meghadoot Theatre Complex, Kamani Auditorium and Rabindra Bhawan lawns and Sahitya Akademi auditorium. It is the only inclusive literary festival in the country that truly represents 24 Indian languages and literature in India. Festival of Letters 2014 sought to reach out to the writers of all age groups across the country. Noteworthy feature of this year was a massive ‘Akademi Exhibition’ with rare collage of photographs and texts depicting the journey of the Akademi in the last 60 years. Felicitation of Sahitya Akademi Fellows was held as a part of the celebration of the jubilee year. The events of the festival included Sahitya Akademi Award Presentation Ceremony, Writers’ Meet, Samvatsar and Foundation Day Lectures, Face to Face programmmes, Live Performances of Artists (Loka: The Many Voices), Purvottari: Northern and North-Eastern Writers’ Meet, Felicitation of Akademi Fellows, Young Poets’ Meet, Bal Sahiti: Spin-A-Tale and a National Seminar on ‘Literary Criticism Today: Text, Trends and Issues’. n exhibition depicting the epochs Adown its journey of 60 years of its establishment organised at Rabindra Bhawan lawns, New Delhi was inaugurated on 10 March 2014. Nabneeta Debsen, a leading Bengali writer inaugurated the exhibition in the presence of Akademi President Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, veteran Hindi poet, its Vice-President Chandrasekhar Kambar, veteran Kannada writer, the members of the Akademi General Council, the media persons and the writers and readers from Indian literary feternity. -

Adaptation of Premchand's “Shatranj Ke Khilari” Into Film

ASIATIC, VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2014 Translation as Allegory: Adaptation of Premchand’s “Shatranj Ke Khilari” into Film Omendra Kumar Singh1 Govt. P.G. College, Dausa, Rajasthan, India Abstract Roman Jakobson‟s idea that adaptation is a kind of translation has been further expanded by functionalist theorists who claim that translation necessarily involves interpretation. Premised on this view, the present paper argues that the adaptation of Premchand‟s short story “Shatranj ke Khilari” into film of that name by Satyajit Ray is an allegorical interpretation. The idea of allegorical interpretation is based on that ultimate four-fold schema of interpretation which Dante suggests to his friend, Can Grande della Scala, for interpretation of his poem Divine Comedy. This interpretive scheme is suitable for interpreting contemporary reality with a little modification. As Walter Benjamin believes that a translation issues from the original – not so much from its life as from its after-life – it is argued here that in Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation Premchand‟s short story undergoes a living renewal and becomes a purposeful manifestation of its essence. The film not only depicts the social and political condition of Awadh during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah but also opens space for engaging with the contemporary political reality of India in 1977. Keywords Translation, adaptation, interpretation, allegory, film, mise-en-scene Translation at its broadest is understood as transference of meaning between different natural languages. However, functionalists expanded the concept of translation to include interpretation as its necessary form which postulates the production of a functionalist target text maintaining relationship with a given source text. -

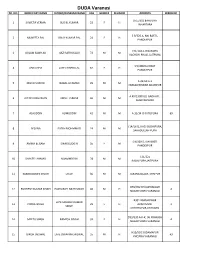

DUDA Varanasi SR

DUDA Varanasi SR. NO. BENIFICARY NAME FATHER/HUSBAND NAME AGE GENDER RELIGION ADDRESS WARD NO D 65/332 BAHULIYA 1 SHWETA VERMA SUSHIL KUMAR 23 F H LAHARTARA S 9/326 A, NAI BASTI , 2 MUNEETA PAL VINAY KUMAR PAL 24 F H PANDEYPUR J 31/118-1-B BANDHU 3 GULAM SABIR ALI HAZI SAFIRULLAH 72 M M KACHCHI BHAG, JAITPURA S 9/408 NAI BAST 4 USHA DEVI LATE CHHEDI LAL 62 F H PANDEYPUR A 33/60 A-1 5 MOHD SHAHID IKABAL AHAMAD 29 M M OMKALESHWAR ADAMPUR A 49/130DULLI GADHAYI , 6 ALTAPU REHAMAN ABDUL JABBAR 46 M M AMBIYAMANDI 7 ALAUDDIN ALIMUDDIN 42 M M A 32/34 CHHITUPURA 89 J 14/16 Q, KAGI SUDHIPURA, 8 AFSANA FATEH MOHMMAD 24 M M SAHADULLAH PURA S 9/369 D, NAI BASTI 9 AMINA BEGAM SIRAGGUDDIN 35 F M PANDEYPUR J 21/221 10 SHAKEEL AHMAD NIJAMMDDIN 28 M M RASALPURA,JAITPURA 11 KAMROODDIN SHEKH ESSUF 36 M M TARANA BAZAR, SHIVPUR D59/352 KH JAIPRAKASH 12 RUDRESH KUMAR SINGH PASHUPATI NATH SINGH 40 M H 4 NAGAR SIGRA VARANASI B301 BANSHIDHAR LATE SANJEEV KUMAR 13 POOJA SINGH 29 F H APARTMENT 2 SINGH CHHITTUPUR,VARANASI D59/330 A-K-K, JAI PRAKASH 14 MEETU SINGH RAMESH SINGH 33 F H 4 NAGAR SIGRA VARANASI N15/592 SUDAMAPUR 15 GIRISH JAISWAL LATE DWARIKA JAISWAL 55 M H 43 KHOJWA VARANASI N15/185 C BIRDOPUR BADI 16 NICKEY SINGH VISHAL SINGH 27 F H GAIBI VARANASI D59/330 AK-1K, JAI 17 PANKAJ PRATAP PRADEEP KUMAR ARYA 23 M H PRAKASH NAGAR SIGRA 4 VARANASI CV14/160 22 A2 18 SANDEEP RAJ KUMAR 29 M H GUJRATIGALI,SONIA 41 VARANASI C12/B LAHANGPURA SIGRA 19 PUSHPA DEVI VIJAY KUMAR 47 F H 41 VARANASI D51/82A-1 SURJAKUND 20 CHANDRASHEKHAR OMPRAKASH 41 M H 67 PURANA PAN DARIBA M15/107, SUDAMAPUR, 21 BHARAT GAUD GOPAL JI GAUD 30 M H KHOJAWAN, VARANASI Bhelupur Zone SR. -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion. -

Gold, Dust, Or Gold Dust Religion in the Life And

GOLD, DUST, OR GOLD DUST? RELIGION IN THE LIFE AND WRITINGS OF PREMCHAND Author(s): Arvind Sharma Source: Journal of South Asian Literature, Vol. 21, No. 2, ESSAYS ON PREMCHAND (Summer, Fall 1986), pp. 112-122 Published by: Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40874091 Accessed: 03-11-2019 20:36 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of South Asian Literature This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Sun, 03 Nov 2019 20:36:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Arvind Sharma GOLD, DUST, OR GOLD DUST? RELIGION IN THE LIFE AND WRITINGS OF PREMCHAND Was Premohand really an athiest? Premchand is regarded as one of the makers of modern Hindi literature and is known to his admirers as the 'king of novelists.1' The purpose of this paper is to examine the place of religion in his life and work. In order to carry out such an examination, however, some preliminary observations are necessary. First of all, the word 'religion' itself will need to be broadly interpre- ted in order to include those modern manifestations of religiosity which are more usually referred to as surrogates for religion, such as Marxism, humanism, nationalism, psychoanalysis, etc., apart from what are traditionally regarded as the religious traditions of mankind, such as Hinduism, etc.