Problematizing Dalit Chetna: Sadgati As the Battleground of Conflict Between the ‘Progressive Casteless Consciousness’ and the Anti-Caste Dalit Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

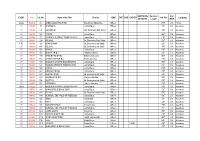

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Sevasadan and Nirmala"

Int.J.Eng.Lang.Lit&Trans.StudiesINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, Vol. LITERATURE3.Issue. 1.2016 (Jan-Mar) AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in KY PUBLICATIONS REVIEW ARTICLE Vol. 3. Issue 1.,2016 (Jan-Mar. ) SPACE AND PERSONHOOD IN PREMCHAND’S "SEVASADAN AND NIRMALA" SNEHA SHARMA Delhi University [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this essay is to examine city architecture and spaces within home in two of Premchand’s novels in an attempt to contextualize certain processes in self- fashioning and production of subjectivities. Every society has prevalent ways of structuring, producing, and conceptualizing space that reflect its dominant ideologies and social order. In other words, spaces are a reflection of social reality. Both these novels document these changing spaces marked by a period of accelerated change. Both these novels, Sevasadan and Nirmala, in the process of narrating the “private in public”, reveal a world shaped by a spatial economy which combines the social relations of reproduction with the relations of production. A knowledge of the spatio- temporal matrix which the characters inhabit, reveals the complex interrelation being formed between the exterior and the interior in a world in the first throes of modernity. The genre of the novel too, as a new form, offers an ideologically charged space, for the author to represent a world experiencing the formation of new socio- geographical settings. KEY WORDS: Modernity, social space, personhood ©KY PUBLICATIONS (Social) space is not a thing among other things, nor a product among other products: rather, it subsumes things produced, and encompasses their interrelationships in their coexistence and simultaneity – their (relative) order and/or (relative) disorder. -

Varanasi Destinasia Tour Itinerary Places Covered

Varanasi Destinasia TOUR ITINERARY PLACES COVERED:- LAMHI – SARNATH – RAMESHWAR – CHIRAIGAON - SARAIMOHANA Day 01: Varanasi After breakfast transfer to the airport to board the flight for Varanasi. On arrival at Varanasi airport meet our representative and transfer to the hotel. In the evening, we shall take you to the river ghat for evening aarti. Enjoy aarti darshan at the river ghat and get amazed with the rituals of lams and holy chants. Later, return to the hotel for an overnight stay. Day 02: Varanasi - Lamhi Village - Sarnath - Varanasi We start our day a little early with a cup of tea followed by a drive to river Ghat. Here we will be enjoying the boat cruise on the river Ganges to observe the way of life of pilgrims by over Ghats. The boat ride at sunrise will provide a spiritual glimpse of this holy city. Further, we will explore the few temples of Varanasi. Later, return to hotel for breakfast. After breakfast we will leave for an excursion to Sarnath and Lamhi village. Sarnath is situated 10 km east of Varanasi, is one of the Buddhism's major centers of India. After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha came to Sarnath where he gave his first sermon. Visit the deer park and the museum. Later, drive to Lamhi Village situated towards west to Sarnath. The Lamhi village is the birthplace of the renowned Hindi and Urdu writer Munshi Premchand. Munshi Premchand acclaimed as the greatest narrator of the sorrows, joy and aspirations of the Indian Peasantry. Born in 1880, his fame as a writer went beyond the seven seas. -

Abstract the Current Paper Is an Effort to Examine the Perspective of Munshi Premchand on Women and Gender Justice

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, {Bi-Monthly}, ISSN 2249-9598, Volume-08, Aug 2018 Special Issue Feminism and Gender Issues in Some Fictional Works of Munshi Premchand Farooq Ahmed Ph.D Research Scholar, Barkatullah University, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh India Abstract The current paper is an effort to examine the perspective of Munshi Premchand on women and gender justice. Premchand’s artistic efforts were strongly determined with this social obligation, which possibly found the best representation in the method in which he treated the troubles of women in his fiction. In contrast to the earlier custom which placed women within the strictures of romantic archives Premchand formulated a new image of women in the perspective of the changes taking place in Indian society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The apprehension with the problem of women in Premchand’s fiction can be largely described as an attempt to discover the various aspects of feminism and femininity and their drawbacks and weaknesses in the socio-cultural condition obtaining in India. The plan was not to suggest a specific resolution or substitute but to highlight the complications involved in the formation of an ideal condition for women. Even when a substitute was recommended there was significant uncertainty. What was significant in the numerous themes pertaining to women which shaped the concern of his fiction was the predicament faced by Indian women in the conventional society influenced by a strange culture. This paper is an effort to examine some of the issues arising out of Premchand’s treatment of this dilemma. KEYWORDS: Feminism, Gender Justice, Patriarchy, Child Marriage, Sexual Morality, Female Education, Dowry, Unmatched Marriage, Society, Nation, Idealist, Realist etc. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Satyajit Ray Season Reveals the Enduring Versatility and Masterly Satyajit Ray: Part Two Style of the Indian Director

22 The second part of our major Satyajit Ray season reveals the enduring versatility and masterly Satyajit Ray: Part Two style of the Indian director. But his later output is marked by a darkening mood that reflects Ray’s This second part of Ray’s career begins And his exquisite historical drama about on a sunny note. The Adventures of the British military takeover of Lucknow ambivalence towards the society he lived in, Goopy and Bagha was his most popular in 1856, The Chess Players, was equally argues Andrew Robinson. film in Bengal, with children and adults concerned with individual morality singing its Bengali songs on the streets as with political systems. But his two for months. ‘Maharaja, We Salute You’ detective films, The Golden Fortress was spontaneously sung by the crowds and The Elephant God, based on his at Ray’s funeral in 1992. own Holmes-and-Watson-style Bengali But then his mood darkened, first into the duo, betrayed a declining belief in official wincing irony of Days and Nights in the justice. In Deliverance, a stark attack on Forest, afterwards into a political trilogy: the cruelty of Untouchability, Ray moved The Adversary, Company Limited about as far from the hopefulness of and The Middleman. From 1969, the Pather Panchali as it was possible to go. Naxalite movement inspired by Maoism Ray’s last three films, though not without rocked Bengal through terrorist acts his trademark comedy, were urgent by young Bengalis, followed by horrific warnings to his fellow citizens against police and army reprisals, and a period religious fundamentalism and social of national Emergency declared by Indira corruption. -

Adaptation of Premchand's “Shatranj Ke Khilari” Into Film

ASIATIC, VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2014 Translation as Allegory: Adaptation of Premchand’s “Shatranj Ke Khilari” into Film Omendra Kumar Singh1 Govt. P.G. College, Dausa, Rajasthan, India Abstract Roman Jakobson‟s idea that adaptation is a kind of translation has been further expanded by functionalist theorists who claim that translation necessarily involves interpretation. Premised on this view, the present paper argues that the adaptation of Premchand‟s short story “Shatranj ke Khilari” into film of that name by Satyajit Ray is an allegorical interpretation. The idea of allegorical interpretation is based on that ultimate four-fold schema of interpretation which Dante suggests to his friend, Can Grande della Scala, for interpretation of his poem Divine Comedy. This interpretive scheme is suitable for interpreting contemporary reality with a little modification. As Walter Benjamin believes that a translation issues from the original – not so much from its life as from its after-life – it is argued here that in Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation Premchand‟s short story undergoes a living renewal and becomes a purposeful manifestation of its essence. The film not only depicts the social and political condition of Awadh during the reign of Wajid Ali Shah but also opens space for engaging with the contemporary political reality of India in 1977. Keywords Translation, adaptation, interpretation, allegory, film, mise-en-scene Translation at its broadest is understood as transference of meaning between different natural languages. However, functionalists expanded the concept of translation to include interpretation as its necessary form which postulates the production of a functionalist target text maintaining relationship with a given source text.