Portrayal of the Marginalized in Satyajit Ray's Sadgati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

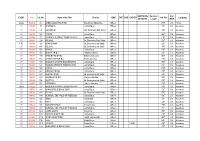

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Satyajit Ray Season Reveals the Enduring Versatility and Masterly Satyajit Ray: Part Two Style of the Indian Director

22 The second part of our major Satyajit Ray season reveals the enduring versatility and masterly Satyajit Ray: Part Two style of the Indian director. But his later output is marked by a darkening mood that reflects Ray’s This second part of Ray’s career begins And his exquisite historical drama about on a sunny note. The Adventures of the British military takeover of Lucknow ambivalence towards the society he lived in, Goopy and Bagha was his most popular in 1856, The Chess Players, was equally argues Andrew Robinson. film in Bengal, with children and adults concerned with individual morality singing its Bengali songs on the streets as with political systems. But his two for months. ‘Maharaja, We Salute You’ detective films, The Golden Fortress was spontaneously sung by the crowds and The Elephant God, based on his at Ray’s funeral in 1992. own Holmes-and-Watson-style Bengali But then his mood darkened, first into the duo, betrayed a declining belief in official wincing irony of Days and Nights in the justice. In Deliverance, a stark attack on Forest, afterwards into a political trilogy: the cruelty of Untouchability, Ray moved The Adversary, Company Limited about as far from the hopefulness of and The Middleman. From 1969, the Pather Panchali as it was possible to go. Naxalite movement inspired by Maoism Ray’s last three films, though not without rocked Bengal through terrorist acts his trademark comedy, were urgent by young Bengalis, followed by horrific warnings to his fellow citizens against police and army reprisals, and a period religious fundamentalism and social of national Emergency declared by Indira corruption. -

Pather Panchali Satyajit RAY - Inde - 1955

Cycle « Pour Krishna » 1/3 Pather Panchali Satyajit RAY - Inde - 1955 Fiche technique Scénario : Satyajit Ray d'après le roman Pather Panchali de Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay Directeur de la photo : Subatra Mitra Décors : Bansi Chandragupta Musique : Ravi Shankar Montage : Dulal Dutta Production : Satyajit Ray Distribution : Parafrance films Interprétation : Karuna Bandyopadhyay (Sarbojaya Ray, la mère de Durga et Apu), Kanu Banerjee (Harihar Ray, le père), Uma Das Gupta (Durga Ray), Subir Bannerjee (Apurba « Apu » Ray), Chunibala Devi (Indir, la parente âgée) Durée : 115 min Sortie Inde : 26 août 1955 Prix du document humain, Cannes 1956 Sortie France : 16 mars 1960 Critique et Commentaires […] C'est par les yeux d'Apu, un petit garçon de sept ans, turbulent et sauvage, que nous découvrons les menus faits tour à tour dramatiques et cocasses qui constituent la trame des jours, des saisons, des années. Pather Panchali pourtant n'a rien d'un film d'enfant. C'est une œuvre au contraire puissamment élaborée, dont la pureté, la simplicité, la calme lucidité, sont du domaine de la méditation. Par son sentiment de la nature, nullement romantique mais mystique, par cette poésie virgilienne qui sait si bien rattacher les êtres et les choses à la terre ancestrale, Satyajit Ray se révèle dans Pather Panchali digne du grand Flaherty. Mais dans son évocation du monde indien d'aujourd'hui, évocation où la pudeur de l'expression donne plus de prix encore à ce que peuvent avoir de pathétique certaines images, le réalisateur témoigne de son admiration (admiration à plusieurs reprises publiquement affirmée) pour Vittorio de Sica. Et de ce double courant, contemplatif et réaliste, naît un charme auquel il me semble difficile de résister. -

(1): Special Issue 100 Years of Indian Cinema the Changing World Of

1 MediaWatch Volume 4 (1): Special Issue 100 Years of Indian Cinema The Changing World of Satyajit Ray: Reflections on Anthropology and History MICHELANGELO PAGANOPOULOS University of London, UK Abstract The visionary Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) is India’s most famous director. His visual style fused the aesthetics of European realism with evocative symbolic realism, which was based on classic Indian iconography, the aesthetic and narrative principles of rasa, the energies of shakti and shakta, the principles of dharma, and the practice of darsha dena/ darsha lena, all of which he incorporated in a self-reflective way as the means of observing and recording the human condition in a rapidly changing world. This unique amalgam of self-expression expanded over four decades that cover three periods of Bengali history, offering a fictional ethnography of a nation in transition from agricultural, feudal societies to a capitalist economy. His films show the emotional impact of the social, economic, and political changes, on the personal lives of his characters. They expand from the Indian declaration of Independence (1947) and the period of industrialization and secularization of the 1950s and 1960s, to the rise of nationalism and Marxism in the 1970s, followed by the rapid transformation of India in the 1980s. Ray’s films reflect upon the changes in the conscious collective of the society and the time they were produced, while offering a historical record of this transformation of his imagined India, the ‘India’ that I got to know while watching his films; an ‘India’ that I can relate to. The paper highlights an affinity between Ray’s method of film-making with ethnography and amateur anthropology. -

Satyajit Ray 1921-1992 Léo Bonneville

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:34 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Satyajit Ray 1921-1992 Léo Bonneville Number 161, November 1992 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/50140ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Bonneville, L. (1992). Satyajit Ray 1921-1992. Séquences, (161), 42–43. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1992 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ HOMMAGE Satyajit Ray 1921 -1992 Jusqu'à la réalisation de Joueurs d'échecs (1977), tous les classique par mois. Puis il se régale à lire des partitions dont il films de Satyajit Ray étaient en bengali. En conséquence, la fait ses livres de chevet. Dès 1961, il composera la musique de majorité des critiques de son pays (où l'on rencontre dix-huit ses films. idiomes) ne les comprenaient pas. Pourquoi? Ses films n'étaient pas sous-titrés chez lui. Ray en conclut: «C'est banal en Inde d'être anti-Ray.» Il n'y a pas que la langue qui faisait problème. Il y avait aussi le tableau que le cinéaste offrait de son pays. -

DOSSIER DE PRESSE Editorial

16ème FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE CINÉMA ASIATIQUE DE TOURS DOSSIER DE PRESSE Editorial Création/transmission Le cinéma plus encore que tous les autres arts, parce qu'il est enfant des fêtes foraines et des recherches formelles, est toujours écartelé entre la reconnaissance populaire et la création artistique. Toucher le plus grand nombre sans vendre son âme au diable reste souvent l'idéal de tout artiste. Rester maître de son art sans trop de compromis n'est pas un problème nouveau, la star du cinéma bengali y était déjà confrontée dans Le Héros de Satyajit Ray. Le réalisateur de Director's Cut de Park Joon-Bum doit mener un dur combat pour ne pas céder aux pressions. La création artistique peut sauver des vies comme celle de Charulata (S. Ray), en questionner d'autres comme celles de George Orwell (Une histoire birmane) ou du metteur en scène de théâtre de The Undying Dream we Have. Le Chant du phénix, film testament (le dernier), du réalisateur chinois Wu Tian Ming nous parle de musique mais aussi de cinéma : celui de la 4ème génération, dont il était le fer de lance, trop souvent oubliée, effacée par les réalisateurs de la 5ème génération : Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige... Le festival cette année fait la part belle au cinéma coréen et comme d'habitude aux inédits et à de très nombreuses avant-premières. Vous pourrez y rencontrer de nombreux invités : Yolande Moreau, Zoltan Mayer, Jinsei Tsuji, Alain Mazars, Freddy Nodolny Poustochkine, Frank Ternier, Kazuo Yamaki, Maho, Leonardo Haertling... Le prix du jury (La Toile de lumière, oeuvre de Guy Romer) sera décerné ainsi que votre prix, celui du public lors de la soirée de clôture le mardi 24 mars 2015. -

From Transcontextualization to Transcreation: a Study of the Cinematic Adaptations of the Short Stories of Premchand

Journal of the Department of English Vidyasagar University Vol. 12, 2014-2015 From Transcontextualization to Transcreation: A Study of the Cinematic Adaptations of the Short Stories of Premchand Anuradha Ghosh Cinematic transcreations of short stories follow a trajectory that is different from adaptations of novels. While compression of events as well as sequences become almost mandatory in terms of a technique of adapting a novel into film, short stories owing to their brevity (not necessarily depth) lead themselves better to cinematic adaptations. Sometimes expansion of motifs and symbols become necessary in order to reproduce visually what has been rendered verbally on a page. It is also not uncommon to see how at times the narrative order of a short story is reproduced cinematically, though the hall-mark of a successful adaptation is not to see whether a one-to-one correspondence between the word and the image has been established. For a successful cinematic transcreation of a fictional piece, what is perhaps most important is the notion of transcontextualization, as unless the film text is able to ‘politically’ address the socio-cultural context in which it has been created, it cannot work within the target language situation. The film (whether an adaptation or a creative construction) must be able to speak to the context in which it is made, taking the spirit of the source text, albeit in a mode that may be altered but simultaneous at the same time as well. Again the adapted text must have a life of its own, taking within its sweep, as it were the ‘after-word’1 of the source text to aesthetic dimensions that are divergent as well as new.