Guest Editor's Column

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will and Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

AGANTUK – The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will And Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri It’s impossible to record the transition in the socio-political and cultural landscape of India in general and Bengal in particular without taking into account the contribution of Satyajit Ray. As author Peter Rainer says, ‘In Ray’s films the old and the new are inextricably joined. This is the great theme of all his movies: the way the past in India forever bleeds through the present.’ Today, Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood, has found a global market. But it may be useful to remember that if anyone can be credited with putting Indian cinema on the world map, it is Satyajit Ray. He pioneered a whole new sensibility about films and filmmaking that compelled the world to reshape its perception of Indian cinema. ‘What we need,’ he wrote in 1947, before he ever directed a film, ‘is a style, an idiom, a part of the iconography of cinema which would be uniquely and recognizably Indian.’ This Still from the documentary, The Music of Satyajit Ray he achieved, and yet, like all great artists, his films went Watch film here- https://bit.ly/3u8orOD beyond the frontiers of countries and cultures. His contribution to the cultural scene in India is limited not just to his work as a director. He was the Renaissance man of independent India. As a film-maker he handled almost all the departments on his own – he wrote the screenplay and dialogues for his film, he composed his own music, designed the promotional material for his films, designed his own posters, went on to handle the cinematography and editing, was actively involved in the costumes (literally sketching each and every costume in a film). -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Portrayal of Environment in Cinema: a Comparative Study of 'Pather Panchali'

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 3; Issue 5; May 2017; Page No. 45-48 Portrayal of environment in cinema: A comparative study of ‘Pather panchali’ & ‘Dreams’ Ram Prakash Dwivedi Department of Hindi journalism & Mass Communication, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) and Akira Kurosawa (1910-198) are the world-famous filmmakers. Coincidentally, they were contemporary and friends. They were also sources of inspiration for each other. Their films are a landmark example of creative cine-language. In most of their movies, nature and the environment are as important as the human characters. Rather, the human being is guided by the nature to act upon. Their movies incorporate nature as an essential component for human activities. Portrayal of nature, in Ray’s movies, is different from that of Kurosawa. To Ray’s films environment and nature comes as part of daily life or seasonal change, whereas Kurosawa represents nature as phenomena like rain, volcanic eruptions, tsunami and earthquakes. This difference is the result of separate geographical conditions of India and Japan. Japan is environmentally very sensitive country, whereas India, due to its larger landmass, does not feel such sensitivity. Pather Panchali (1955) is considered as a masterpiece of parallel cinema and reflects reality. The film was made with on location shooting technique. This film, therefore, depicts the nature and environment of Bengal. In Dreams (1990) imagination is more important than reality. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

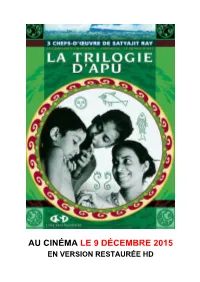

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

Speaking Through Troubled Times

Speaking through Troubled Times Moinak Biswas I would like to talk about the encounter between cinema and a moment in our political history in this essay. Is it possible to identify the voices that cinema sifts out of a time, and make them narrate to us a story that was there in the films but not told? I would like to ask that question about the cusp of the nineteen sixties and seventies. 1. There now exists a sizeable literature on the relationship between history and cinema. Academic historians have looked at the relationship mainly in terms of representation of the past. The fragile status that facts attain in a popular medium was the starting point of historians’ serious engagement with film, the more sophisticated version of which took up the issue of concretization of the past on screen, the process of giving body to a time that is gone, and the necessary ambivalence that it brings on. The other focus of the discussion has been narrative of course, the relationship of the events in history as they appear on screen. Since the larger historians’ debate had narrative as the cardinal point of contention - narrativity as a category came to problematize the entire question of truth-telling in historiography in the wake of semiotic criticism - the filmic imperatives of sequencing of events from the past has been another cause of concern. Professional historians such as Natalie Davis and Robert Rosenstone have written on these questions quite extensively [1], as have Daniel Walkowitz, R. C. Raack and Robert Brent Toplin, all of whom have developed strong ties with film and television production, as advisors and screenwriters [2]. -

Reflections of Radical Political Movements on the Silver Screen: an Analysis

Global Media Journal-Indian Edition; Volume 12 Issue1; June 2020. ISSN:2249-5835 Reflections of Radical Political Movements on the Silver Screen: An Analysis Aakash Shaw Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Vivekananda College (Affiliated to the University of Calcutta) [email protected] Abstract Jean – Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni described film as a particular product, manufactured within given economic relations, and involving labour to produce. This is a condition to which ‘independent film-makers’ and the ‘new cinema’ are subject, involving a number of workers and as a material product it is also considered as an ideological product of the system. No film makers can by individual efforts, change the economic relations governing the manufacture and distribution of her/his films. The radical political movements which culminated from the peasant uprising in 1967, spread like firestorm and eventually turned out to be an urban phenomenon. Films invoke current evaluations founded upon new criteria which are marked by the representation of power structures, authoritative institutions, engaging contestations and ideological apparatuses frozen in a specific time and space. Film reproduces reality that is an expression of prevailing ideology and seeks to re-interpret or find inferences and possible explications of the discourse from the past. In the context of radical political movements, the paper seeks to understand and analyze cinematic portrayal of Naxalite movement not only as peasants uprising but as a socio-economic approach arising as a response to the exploitation and subjugation prevalent in the semi-feudal and semi-colonial socio-economic structure. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Satyajit Ray Retrospective Opens Film India

Ill The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 39 *o For Immediate Release 5/26/81 COMPLETE SATYAJIT RAY RETROSPECTIVE OPENS FILM INDIA Artist, author, musician, and master filmmaker SATYAJIT RAY will introduce FILM INDIA, the largest and most comprehensive program of Indian cinema ever exhibited in this country. Presented by The Department of Film in conjunction with The Asia Society and the Indo-US Subcommission on Education and Culture, FILM INDIA is designed to broaden American awareness of the long history of Indian cinema as well as of the recent developments in Indian filmmaking. FILM INDIA is structured in three parts. The first section will comprise a retrospective of films (with English subtitles) of the internationally acclaimed director Satyajit Ray, including shorts and features that have not been previously exhibited in this country. Many new 35mm prints of Ray's films are being made specifically for this program, including his most recent feature, THE KINGDOM OF DIAMONDS (1980) and an even later work, PIKOO (1980), a short film. The complete Ray retrospective totals 29 films, June 25 - July 24. Satyajit Ray (Calcutta, 1921) was born into a distinguished Bengali family. After working for some years as an art director in an advertising firm, he completed — against tremendous odds — his first film, PATHER PANCHALI, in 1955. Its premiere at The Museum of Modern Art in May 1955, its acclaim at the 1956 Cannes Film Fest ival, and its immediate success throughout Bengal, encouraged Ray and enabled him to become a professional filmmaker. PATHER PANCHALI was followed by two sequels, forming the now famous APU Trilogy.