From Transcontextualization to Transcreation: a Study of the Cinematic Adaptations of the Short Stories of Premchand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Course Pattern

HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) TIRUCHIRAPPALLI-620002 DEPARTMENT OF HINDI Course Pattern 2018-2019 SI.No. Course code Semester Course Title Credits Hrs/wk Marks Hindi – I 1. I Prose, Short 3 6 100 U18HN1HIN01 Story And Grammar –I Hindi – II 2. U18HN2HIN02 II Drama, Novel 3 5 100 And Grammar –II Hindi -III 3. U18HN3HIN03 III Medieval– 3 6 100 Modern Poetry And History Of Hindi Literature-1 (Veergadha Kal Aur Bakthi Kal) Hindi IV 4. U18HN4HIN04 IV Functional 3 5 100 Hindi And Translation (For the candidates admitted from June 2018 onwards) HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) TIRUCHIRAPPALLI-620002 DEPARTMENT OF HINDI SEMESTER – I Course Title PART – I LANGUAGE HINDI – I PROSE, SHORT STORY AND GRAMMAR –I Total Hours 90 Hours/Week 6Hrs/Wk Code CODE: U18HN1HIN01 Course Type Theory Credits 3 Marks 100 General Objective : To enable the students to understand the importance of human values and patriotism Course Objectives (CO): The learner will be able to: CO No. Course Objectives CO -1 Evaluate Self Confidence, Human values CO- 2 Understand and analyze Gandhian Ideology CO- 3 Understand Indian Culture, custom CO- 4 Analyze communal Harmony and Unity in Diversity CO- 5 Evaluate Friendship UNIT – I (18 Hours) 1. Aatma Nirbharatha 2. Idgah 3. Sangya Extra Reading (Key Words ): Takur ka kuvam, Bhuti Kaki UNIT- II (18 Hours) 1. Mahatma Gandhi 2. Vusne Kaha Tha 3. Sarva Naam Extra Reading (Key Words ): Chandradhar Sharma Guleri, Gandhian Ideology UNIT- III (18 Hours) 1. Sabhyata Ka Rahasya 2. Karva Va Ka Vrat 3. Visheshan Extra Reading (Key Words ): Sabhyata Aur Sanskriti, Yashpal ki Sampoorna khaniyan UNIT- IV (18 Hours) 1. -

A Stylistic Study of Multiple English Translations of Premchand's

Loss and Gain in Translation from Hindi to English: A Stylistic Study of Multiple English Translations of Premchand’s Godaan and Nirmala THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH By TOTA RAM GAUTAM UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. MOHD. ASIM SIDDIQUI DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH, INDIA. 2011 There are two lasting bequests we can give our children. One is roots. The other is wings. – Hodding Carter, Jr. TO My Mother and My Father Loss and Gain in Translation from Hindi to English: A Stylistic Study of Multiple English Translations of Premchand’s Godaan and Nirmala ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH By TOTA RAM GAUTAM UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. MOHD. ASIM SIDDIQUI DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH, INDIA. 2011 Abstract Although translation is an old phenomenon, it is only after the 1970s that it develops as an academic discipline. Nevertheless in the comparatively short period of the last five decades, it has developed enormously. Today it is multi-disciplinary in nature and can boast many publications. Recent developments have also created formal training programs and translation associations. However, inspite of all these developments, its scope has mainly been superficial as most of the studies focus on general aspects of a translation. That said, the present study specifically takes up Hindi English translation tradition and closely explores problems, issues and possibilities in translation from Hindi to English. To accomplish this task, the researcher structurally divides the study in seven chapters. -

LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY 2014-15 FACULTY of Arts and Languages

A dissertation on Social Dominance and Subaltern Consciousness in The Gift of a Cow and The Outcaste Submitted to LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in English 2014-15 FACULTY OF Arts and Languages LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY PUNJAB Submitted by: Supervised by: Rahul Singh Sundram Dr. Sanjay Prasad Pandey Reg. no: 11412891 Asst. Professor Dept. of English 1 DECELARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation entitled Social dominance and Subaltern Consciousness in The Gift of Cow and The Outcaste submitted for the M.Phil degree is entirely my original work, and all the ideas and references have been duly acknowledged. It does not contain any work for award of any other degree or diploma at any university. Research Scholar, Rahul Singh Sundram 2 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Rahul Singh Sundram has completed his M.Phil dissertation entitled “Social Dominance and Subaltern Consciousness in The Gift of a Cow and The Outcaste under my guidance and supervision. To the best of my knowledge, the present work is the result of his original investigation and study. No part of the dissertation has ever been submitted for any other degree or diploma at any university. This dissertation is fit for the submission and partial fulfillment of the conditions for the award of Master of Philosophy in English. Date: Dr. Sanjay Prasad Pandey Assistant Professor 3 Abstract This Dissertation looks at the Social Dominance and oppression which has been continued to be a serious issue of concern in India since the existence of human being. -

9. Internationales Berlin Forum 22.2.-3.3. Des Jungen Films 1979

29. internationale filmfestspiele berlin 9. internationales berlin forum 22.2.-3.3. des jungen films 1979 INTERVIEW überwindet der Film die Grenzen von Zeit und Raum, um zu einer universellen Wahrheit zu gelangen. Am Ende des Films wird der junge Held aus seiner gewohnten Um• Land Indien 1971 gebung herausgeholt und von einem unsichtbaren Zuschauer einem Produktion Mrinal Sen Verhör unterworfen; auf provokative Fragen gibt er unsichere Ant• worten. Und schließlich kommt der Moment des Urteils — über die Welt und ihre Werte. Regie Mrinal Sen Mrinal Sen Buch Mrinal Sen, nach einer Erzählung von Ashish Burman Biofilmographie Kamera K.K. Mahajan Mrinal Sen wurde 1923 geboren. „Ich kam auf Umwegen zum Film. Musik Vijay Raghava Rao Ich habe Physik studiert, interessierte mich für akustische Phäno• mene, und um diese eingehender zu untersuchen, arbeitete ich nach Schnitt Gangadhar Naskar Beendigung meines Studiums in einem Filmstudio. Als ich dann in der Nationalbibliothek in Kalkutta meine Arbeit fortsetzte, begann Darsteller ich auch Filmliteratur zu lesen — Schriften Sergej Eisensteins, die Ranjit Mullick Ranjit Mullick Arbeit seines Schülers Wladimir Nilsen, die Aufsätze Wsewolod Sekhar Chatterjee Sekhar Chatterjee Pudowkins. Die Mutter Karuna Banerjee Dann habe ich andere Sachen versucht, habe Korrektur gelesen und Mithu (die Schwester) Mamata Banerjee Artikel geschrieben und war kurze Zeit bei einer Theaterkooperati• Bulbul ve, dem 'Indian People's Theatre Movement'. (die Freundin) Bulbul Mukerjee Ich begann für eine Zeitung der Kommunistischen Partei, deren Mit• arbeiter ich war, Filmrezensionen zu schreiben." Die im Film verwendete Telephonnummer ist Mrinal Sens 1952 veröffentlichte Sen ein Buch über Charlie Chaplin. Um sich eigene Telephonnummer finanziell über Wasser zu halten, wurde er Vertreter einer Arznei• mittelfirma, ein Beruf, „für den ich vollkommen ungeeignet war". -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed ISSN: 2456-7507 postscriptum.co.in Volume II Number i (January 2017) Nag, Sourav K. “Decolonising the Eerie: ...” pp. 41-50 Decolonising the Eerie: Satyajit’s Bhooter Raja (the King of Ghosts) in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Sourav Kumar Nag Assistant Professor in English, Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya, Bankura The author is an assistant professor of English at Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya. He has published research articles in various national and international journals. His preferred literary areas include African literature, Literary Theory and Indian English Literature. At present, he is working on his PhD on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Abstract This paper is a critical investigation of the socio-political situation of the Indianised spectral king (Bhooter Raja) in Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and also of Ray’s handling of the marginalised in the movie. The movie is read as an allegory of postcolonial struggle told from a regional perspective. Ray’s portrayal of the Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) is typically Indianised. He deliberately deviates from the colonial tradition of Gothic fiction and customised Upendrakishore’s tale as a postcolonial narrative. This paper focuses on Ray’s vision of regional postcolonialism. Keywords ghost, eerie, postcolonial, decolonisation, subaltern Nag, S. K. Decolonising the Eerie ... 42 I cannot help being nostalgic sitting on my desk to write on Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation of Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne (1969). I remember how I gaped to watch the movie the first time on Doordarsan. Not being acquainted with Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) before, I got startled to see the shiny black shadow with flashing electric bulbs around and hearing his reverberated nasal chant of three blessings. -

Oct-Dec-Vidura-12.Pdf

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 October-DecemberJULY - SEPTEMBER 2012 2011 VOLUMEVolume 3 4 IssueISSUE 4 Rs 3 50 RS. 50 In a world buoyed by TRP ratings and trivia, QUALITY JOURNALISM IS THE CASUALT Y 'We don't need no thought control' n High time TAM/TRP era ended n The perils of nostalgia n You cannot shackle information now n Child rights/ child sexual abuse/ LGBT youth n Why I admire Justice Katju n In pursuance of a journalist protection law Responsible journalism in the age of the Internet UN Women: Promises to keep Your last line of defence n Alternative communication strategies help n The varied hues of community radio Indian TV news must develop a sense of The complex dynamics of rural Measuring n Golden Pen of Freedom awardee speaks n Soumitra Chatterjee’s oeuvre/ Marathi films scepticism communication readability n Many dimensions to health, nutrition n Tributes to B.K. Karanjia, G. Kasturi, Mrinal Gore Assam: Where justice has eluded journalists Bringing humour to features Book reviews October-December 2012 VIDURA 1 FROM THE EDITOR Be open, be truthful: that’s the resounding echo witch off the TV. Enough of it.” Haven’t we heard that line echo in almost every Indian home that owns a television set and has school-going children? “SIt’s usually the mother or father disciplining a child. But today, it’s a different story. I often hear children tell their parents to stop watching the news channels (we are not talking about the BBC and CNN here). -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

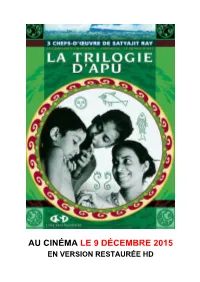

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray.