Otankik on the Edge of the World That Bore Chicagou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin ON ATI RM FO K CREE MILLER 0 20 40 mi Douglas Member 0 50 km Lake ? Crab Member EDITORS C O Kent M. Syverson P P Florence Member E R Lee Clayton F Wildcat A Lake ? L L Member Nashville Member John W. Attig M S r ik be a F m n O r e R e TRADE RIVER M a M A T b David M. Mickelson e I O N FM k Pokegama m a e L r Creek Mbr M n e M b f a e f lv m m i Sy e l M Prairie b C e in Farm r r sk er e o emb lv P Member M i S ill S L rr L e A M Middle F Edgar ER M Inlet HOLY HILL V F Mbr RI Member FM Bakerville MARATHON Liberty Grove M Member FM F r Member e E b m E e PIERCE N M Two Rivers Member FM Keene U re PIERCE A o nm Hersey Member W le FM G Member E Branch River Member Kinnickinnic K H HOLY HILL Member r B Chilton e FM O Kirby Lake b IG Mbr Boundaries Member m L F e L M A Y Formation T s S F r M e H d l Member H a I o V r L i c Explanation o L n M Area of sediment deposited F e m during last part of Wisconsin O b er Glaciation, between about R 35,000 and 11,000 years M A Ozaukee before present. -

Geologic Resources Inventory Map Document for Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate Geologic Resources Division Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore GRI Ancillary Map Information Document Produced to accompany the Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) Digital Geologic Data for Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore indu_geology.pdf Version: 3/4/2014 I Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Map Document for Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore Table of Contents Geologic R.e..s.o..u..r.c..e..s.. .I.n..v.e..n..t.o..r..y. .M...a..p.. .D..o..c..u..m...e..n..t....................................................................... 1 About the N..P..S.. .G...e..o..l.o..g..i.c. .R...e..s.o..u..r.c..e..s.. .I.n..v.e..n..t.o..r..y. .P...r.o..g..r.a..m........................................................... 2 GRI Digital .M...a..p.. .a..n..d.. .S..o..u..r.c..e.. .M...a..p.. .C..i.t.a..t.i.o..n............................................................................... 4 Map Unit Li.s..t.......................................................................................................................... 5 Map Unit De..s..c..r.i.p..t.i.o..n..s............................................................................................................. 7 Qlmm - Fille..d.. .a..n..d.. .m..o..d..i.f.i.e..d../.d..i.s..t.u..r.b..e..d.. .l.a..n..d.. .(.H..o..l.o..c..e..n..e..).................................................................................................. 7 Qlma1 - Ch.a..n..n..e..l. .a..n..d.. .f.l.o..o..d..p..l.a..in.. .(..H..o..l.o..c..e..n..e..)................................................................................................................. 7 Qlma2 - Ch.a..n..n..e..l. .a..n..d.. .f.l.o..o..d..p..l.a..in. -

Behavior of the James Lobe, South Dakota During Termination I

Behavior of the James Lobe, South Dakota during Termination I A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Geology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences by Stephanie L. Heath MSc., University of Maine BSc., University of Maine July 18, 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas V. Lowell Dr. Aaron Diefendorf Dr. Aaron Putnam Dr. Dylan Ward i ABSTRACT The Laurentide Ice Sheet was the largest ice sheet of the last glacial period that terminated in an extensive terrestrial margin. This dissertation aims to assess the possible linkages between the behavior of the southern Laurentide margin and sea surface temperature in the adjacent North Atlantic Ocean. Toward this end, a new chronology for the westernmost lobe of the Southern Laurentide is developed and compared to the existing paradigm of southern Laurentide behavior during the last glacial period. Heath et al., (2018) address the question of whether the terrestrial lobes of the southern Laurentide Ice Sheet margin advanced during periods of decreased sea surface temperature in the North Atlantic. This study establishes the pattern of asynchronous behavior between eastern and western sectors of the southern Laurentide margin and identifies a chronologic gap in the western sector. This is the first comprehensive review of the southern Laurentide margin since Denton and Hughes (1981) and Mickelson and Colgan (2003). The results of Heath et al., (2018) also revealed the lack of chronologic data from the Lobe, South Dakota, the westernmost lobe of the southern Laurentide margin. -

Analysis of an Interlobate Boundary in the Wisconsinan Drift of Kalamazoo County and Adjacent Areas in Southwestern Michigan

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1977 Analysis of an Interlobate Boundary in the Wisconsinan Drift of Kalamazoo County and Adjacent Areas in Southwestern Michigan Norman A. Lovan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Lovan, Norman A., "Analysis of an Interlobate Boundary in the Wisconsinan Drift of Kalamazoo County and Adjacent Areas in Southwestern Michigan" (1977). Master's Theses. 2207. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2207 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSIS OF AN INTERLOBATE BOUNDARY IN THE WISCONSINAN DRIFT OF KALAMAZOO COUNTY AND ADJACENT AREAS IN SOUTHWESTERN MICHIGAN by Norman A. Lovan A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 19 77 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ANALYSIS OF AN INTERLOBATE BOUNDARY IN THE WISCONSINAN DRIFT OF KALAMAZOO COUNTY AND ADJACENT AREAS IN SOUTHWESTERN MICHIGAN Norman A. Lovan, M.S. Western Michigan University, 1977 ABSTRACT A detailed investigation of selected textural and mineralogical aspects of tills in southwestern Michigan is used to define an interlobate boundary relationship be tween the Wisconsinan ice of the Lake Michigan and Saginaw lobes. Bedrock underlying the study area contributed lit tle to the bulk composition of the tills investigated. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy Of

The Tinley Moraine in Indiana 1 Allan F. Schneider, Indiana Geological Survey Abstract The Tinley Moraine, which was named in Illinois for a subsidiary ridge behind the main part of the Valparaiso Morainic System, has received little recognition as a discrete moraine in Indiana. Recent mapping sug- gests, however, that ice of the Lake Michigan Lobe probably did recede some unknown distance from its position along the Valparaiso Moraine and then readvanced to form the Tinley Moraine. The Tinley Moraine enters Indiana in west-central Lake County, and its main ridge can be traced for about 20 miles across Lake County and western Porter County. It is more readily recognized as a discrete moraine by ice-block depressions and drainage relations along its distal margin than by its height or good internal morphology. The crest of the Tinley ridge gradually decreases in elevation from 736 feet at the state line to about 700 feet at the eastern end of the segment, where the moraine be- comes obscure near a prominent gap in the Valparaiso Moraine. Here the terminal zone of the Tinley ice apparently curved northward through an arc of about 90 degrees and is represented by an upland till plain that was probably deposited with the ice front standing in a lake. Farther north- east the terminal zone of the ice possibly is marked by an undulating till belt that trends eastward through northeastern Porter County and northeastward through northwestern LaPorte County. This belt has long been considered to be part of the Lake Border Morainic System, which is, however, presumably younger than the Tinley Moraine. -

Guide Leaflet, Geological Science Field Trip, Palos Hills

G#£i SuJ^OLxJ GUIDE LEAFLET 1971 G Reprinted in 1981 PALOS HILLS AREA GEOLOGICAL SCIENCE FIELD TRIP November 12, 1971 Cook and Du Page Counties Palos Park and Sag Bridge 7.5-Minute Quadrangles ^ <*& v^Vv ,o wov David L. Reinertsen Dwain J. Berggren Leaders Illinois Institute of Natural Resources, State Geological Survey Division, Champaign, Illinois 61820 SURVEY ILLINOIS »T»Te0t0LOOICAL 3 3051 00006 9470 . PALOS HILLS GEOLOGICAL SCIENCE FIELD TRIP ITINERARY Line up on West 97th Street at Roberts Road, opposite H. H. Conrady Junior High School, heading west. 0.0 0.0 Turn right (north) on Roberts Road (30th Avenue). We are driving along the Tinley Moraine, a wide belt of gravel and earth ridges that form the higher hills in the Hickory Hills Golf Course west of the road. This belt of ridges is as much as 6 miles wide, and it extends roughly parallel to Lake Michigan and almost continuously from Wisconsin to Indiana. The Tinley Moraine was deposited about 14,000 years ago by a glacier flowing from Canada into Illinois through the trough that now contains Lake Michigan. As the glacier melted, water was trapped between the Tinley Moraine and the ice front. As the ice front melted back into the Lake Michigan basin, a large lake came into being, covering all the land east of the Tinley Moraine. The place covered by the glacial lake--the area that was the lake bed--is called the Chicago Lake Plain. The Chicago Lake Plain is an extremely flat region about 45 miles long and 15 miles wide, bounded on the west by the Tinley Moraine and containing the city of Chicago and many of its suburbs (see figure 1) The lake that formed between the Tinley Moraine and the glacier is called Lake Chicago, and it lasted almost 4,000 years (from about 14,000 years up to about 10,500 years before present) at levels fluctuating between approximately 640 feet and 590 feet MSL (feet above mean sea level). -

Geology of the Chicago Region

STATE OF ILLINOIS WILLIAM G. STRATTON, GoHntor DEPARTMENT OP REGISTRATION AND EDUCA'l'ION VERA M. BINKS, Dj,«UJr DIVISION OP THE STATE GEOLOG ICAL SURVEY M. M. LEIGHTON, Cbl;J URBANA B U L L E T I N N 0 . 65, P A 1t T I I GEOLOGY OF THE CHICAGO REGION PART II-IBEPLEISTOCENE BY J llARLBN BRETZ Pll.INTED BYUTHOlllTY A OF THE STATE O"l' lLLlNOlS URBANA, ILLINOIS 1955 STATE OF ILLINOIS WILLIAM G. STRATTON, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION VERA M. BINKS, Director DIVISION OF THE STATE GEOLOG IC AL SURVEY M. M. LEIGHTON, Chief URBANA B u L L E T I N N 0 . 65, p A RT I I GEOLOGY OF THE CHICAGO REGION PART II - THE PLEISTOCEN E BY J HARLEN BRETZ PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS URBANA, ILLINOIS 1955 ORGANIZATION ST ATE OF ILLINOIS HON. WILLIAM G. STRATTON, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION HON. VERA M. BINKS, Director BOARD OF NATURAL RESOURC ES AND CONS ERVAT IO N HON. VERA M. BINKS, Chairman W. H. NEWHOUSE, PH.D., Geology ROGER ADAMS, PH.D., D.Sc., Chemistry R. H. ANDERSON, B.S., Engineering 0 A. E. EMERSO�. PH.D., Biology LEWIS H. TIFFANY, PH.D., Po.D., Forestry W. L. EVERITT, E.E., PH.D., Representing the President of the University of Illinois DELYTE W. MORRIS, PH.D. President of Southern Illinois University GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVIS IO N M. M. LEIGHTON, PH.D., Chief STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION Natural Resources Building, Urbana M. M. LEIGHTON, PH.D., Chief Esm TOWNLEY, M.S., Geologist and Assistant to the Chief VELDA A. -

Chicagoland Geology and the Making of a Metropolis

Chicagoland Geology and the Making of a Metropolis Field Excursion for the 2005 Annual Meeting Association of American State Geologists June 15, 2005 Michael J. Chrzastowski Open File Series OFS 2005-9 Rod R. Blagojevich, Governor Illinois Department of Natural Resources Joel Brunsvold, Director ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William W. Shilts, Chief 97th Annual Meeting St. Charles Illinois AASG Sponsors The Illinois State Geological Survey and the Association of American State Geologists gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the following organizations and individuals as sponsors of the 2005 Annual Meeting in St. Charles, Illinois. Diamond Sponsors ($5,000 or more) Isotech Laboratories, Champaign, Illinois (Dennis D. Coleman, President and Laboratory Director) Preston Exploration (Arthur F. Preston) Gold Sponsors ($1,000 or more) Bi-Petro (John F. Homeier, President) Illinois Oil and Gas Association William F. Newton Podolsky Oil Company (Bernard Podolsky, President) U.S. Silica Company Silver Sponsors ($500 or more) Anonymous James S. and Barbara C. Kahn Shabica and Associates (Charles Shabica) Excursion Bus Hosts Michael J. Chrzastowski Daniel J. Adomaitis Chicagoland Geology and the Making of a Metropolis Field Excursion for the 2005 Annual Meeting Association of American State Geologists June 15, 2005 Michael J. Chrzastowski Rod R. Blagojevich, Governor Illinois Department of Natural Resources Joel Brunsvold, Director ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William W. Shilts, Chief 615 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820-6964 217-244-2414 www.isgs.uiuc.edu “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work.” Daniel Hudson Burnham (1846–1912) Architect for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held at Chicago and lead author of the 1909 Plan of Chicago. -

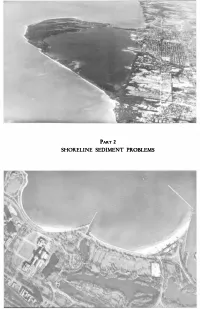

Shoreline Sediment Problems

PART 2 SHORELINE SEDIMENT PROBLEMS CHAPTER 5 GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF GREAT LAKES BEACHES Jack L. Hough Department of Geology University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois ABSTRACT The locations of the Great Lakes and many details of the lake bottom topography bear a distinct relationship to the bed rock structure. Normal stream erosion in pre-glacial time probably etched out the major topographic relief of the region, forming the major basins and even some of the present bays, in the weak rock belts. Glacial ice, advancing over the region in several stages, followed the lowlands but reshaped them and probably deepened most of them. The known lake history, beginning with the last retreat of the ice from the southern rims of the Michigan and £rie basins, involves a number of stages at different levels in each of the basins. These lakes discharged at various places at different times, because of readvancement or retreat of the glacial ice front and because of tilting of the earth's surface. The writer's summary of this history is illustrated by a series of sixteen maps. The practical importance of two extremely low lake stages is pointed out. These have affected foundation conditions in the vicinity of many river mouths. The newly established recency of some of the higher lake stages (Nipissing and Algoma), and the revision of the elevations attained by them, affect estimates of the intensity of beach action and they affect conclusions regarding the time of last discharge of water through the Chicago outlet. INTRODUCTION Many details of the geologic history of the Great Lakes are pertinent to the study of present day shore processes and to foundation problems along the lake shores. -

Geologic Framework and Glaciation of the Eastern Area Christopher L

Boise State University ScholarWorks Anthropology Faculty Publications and Department of Anthropology Presentations 1-1-2006 Geologic Framework and Glaciation of the Eastern Area Christopher L. Hill Boise State University This document was originally published in Handbook of North American Indians. Geological Framework and Glaciation of the Eastern Area CHRISTOPHER L. HILL Late Pleistocene landscapes in glaciated eastern North In the Great Lakes region, the Wisconsin stage has been America included changing ice margins, fluctuating lake divided into a series of chronostratigraphic units (W.H. and sea levels, and deglaciated physical settings that were Johnson et al. 1997; Karrow, Driemanis, and Barnett inhabited by a variety of extinct (Rancholabrean) fauna. 2000). The Altonian substage dates to before 30,500 B.C. , The glaciated East of North America consists of the mid while the Farmdalian substage ranges in age from about continent from Hudson Bay to south of the Great Lakes 30,500 to 28,000 B.C. The Woodfordian substage ranges in and extends eastward to the Atlantic coast. Glaciers were age from about 28,000 to about 12,800 B.C.; it is associated present along the Atlantic coast from southern New York with extensive glacial activity and subsumes previously north to Labrador. used terminology such as Tazewell, Cary, and Mankato Some of this region appears to have been ice-free during (Willman and Frye 1970). The Twocreekan substage is parts of the Middle Wisconsin; the interstadial ice margin a short interval after the Woodfordian and before the around 33,400-29,400 B.C. may have been situated within the Greatlakean, generally ranging 12,800-11,800 B.C. -

(Jijl()F Ll Fl Ii

. State of Illinois De,attment of Registration and Education STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION Morris M. :te·i.ghton;. ·chief (JIJl()f ll�fl Ii GEOLOGICAL SCIENCE FIELD TRIP Sponsored by ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Lake County Waukegan Quadrangle Leader Gilbert O. Raasch Urbana, Illinois October 7, 1950 GUIDE LEAFLET NO. 1950-D HOST: Waukegan High School Waukegan Geological Science Fieid Trip Part I Itinerary o.o 0. 0 Caravan assembles on south side of Waukegan Township High School, headed,, southwest. on north siae of Glenrock.Avenue. O.O 0. 0 Turn left, south, on Jackson Street. 0.2 0.2 Traffic light. Continue ahead, turn immediately half-right, southwest, on blacktop road (Dugdale Avenue), and cross railroad. 0. 7 0.9 Stop sign. Continue ahead, southwest, on Dugdale Road. Route traverses rolling glacial topography of the Highland Park Moraine. 2.0 2. 9 Stop sign. Turn diagonal left, southeast, on Route 131. 0.8 3. 7 CAUTION. Entrance to Great Lakes '.Na'l-al Training Center. Co.ntinue.ahead on Route 131. 1. 7 5.4 Stop 1. Crest of the Highland Park Moraine. Remain in ears. This stop is on narrow crest of the Highland Park Moraine which runs in a general north-south direction and here slopes steeply on both its east and west sides. When the rate of melting of the glacial ice balances the rate of a glacier's movement, the ice front remains stationary. Here the rock and earth pushed in front of the ice, and freed by the melting of the ice, accumulate. When the glacier finally melts away, a ridge remains to mark the line of this ancient stalemate. -

PDF Linkchapter

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abbott Formation, Illinois, 251 Michigan, 287 beetle borrows, Nebraska, 11 Acadian belt, 429 Archean rocks beetles, Manitoba, 45 Acadian orogeny Michigan, 273, 275 Belfast Member, Brassfield Illinois, 243 Minnesota, 47, 49, 53 Formation, Ohio, 420, 421 Indiana, 359 Wisconsin, 189 Bellepoint Member, Columbus Acrophyllum oneidaense, 287 Arikaree Group, Nebraska, 13, 14, Limestone, Ohio, 396 Adams County, Ohio, 420, 431 15, 25, 28 Belleview Valley, Missouri, 160 Adams County, Wisconsin, 183 Arikareean age, Nebraska, 3 Bellevue Limestone, Indiana, 366, Admire Group, Nebraska, 37 arthropods 367 Aglaspis, 83 Iowa, 83 Bennett Member, Red Eagle Ainsworth Table, Nebraska, 5 Missouri, 137 Formation, Nebraska, 37 Alexander County, Illinois, 247, 257 Ash Hollow Creek, Nebraska, 31 Benton County, Indiana, 344 algae Ash Hollow Formation, Nebraska, 1, Benzie County, Michigan, 303 Indian, 333 2, 5, 26, 29 Berea Sandstone, Ohio, 404, 405, Michigan, 282 Ash Hollow State Historical Park, 406, 427, 428 Missouri, 137 Nebraska, 29 Berne Conglomerate, Logan Ohio, 428 asphalt, Illinois, 211 Formation, Ohio, 411, 412, 413 Alger County, Michigan, 277 Asphalting, 246 Bethany Falls Limestone Member, Algonquin age, Michigan, 286, 287 Asterobillingsa, 114 Swope Formation, Missouri, Allamakee County, Iowa, 81, 83, 84 Astrohippus, 26 135, 138 Allegheny Group, Ohio, 407 Atherton Formation, Indiana, 352 Bethany Falls Limestone, Iowa, 123 Allen County, Indiana, 328, 329, 330 athyrids, Iowa, 111 Betula, 401 Allensville