The Royal Navy Today: Reality, Aspiration Or Pretence?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submarine Delivery Agency Corporate Plan 2019 to 2022

Submarine Delivery Agency Corporate Plan 2019-2022 November 2019 1 Contents Section Chapter Page 1 Foreword by the Secretary of State for Defence 3 2 Introduction by the SDA Chair and Chief Executive 4 3 Our Background 5 4 Our Vision and Purpose 6 5 Our Strategic Objectives 7 6 How We Are Governed 9 7 How We Deliver 11 8 What We Deliver 14 9 Looking Out to 2022 17 Annex A – Submarine Delivery Agency Key Performance Indicators 19 2 1. Foreword by the Secretary of State for Defence I am delighted to introduce the 2019 - 2022 Corporate Plan for the Submarine Delivery Agency (SDA), which sets out the intent for delivery of this essential part of Defence. The Continuous at Sea Deterrent (CASD) is the cornerstone of our national security, reaffirmed by Parliament in 2016, and its delivery demands a strong and clear focus. Our Defence Purpose is to protect the people of the UK, prevent conflict, and be ready to fight the UK’s enemies. Our submarine capability ensures we are prepared for the present. It also guarantees we are fit for the future and provides the ultimate guarantee of our safety for the next 50 years and beyond. In its first year of operation, the SDA has made great strides to sustain the readiness and availability of our current and future key defence capabilities. I have seen the real progress being made on the ground in delivering our submarines in build and ensuring that our in-service fleet is able to fulfil its missions. We have seen commitments of around £2.5Bn to support the second phase of the Dreadnought programme so far. -

September 2012

Twinned with SAOC East September 2012 Submariners Association ▪ Barrow-in- Furness Branch Newsletter ▪ Issue 147 [email protected] HMS Upholder The September Ian stated after the Church service and the Cremation that he was pleased to see so Word many Submariners in the congregation in In the absence of our Illustrious leader uniform, although it was stressed that no Dave Barlow who is on Holiday (Lovely black was to be worn. He has also stated Weather for it), I have the honour of that he will continue attending the delivering the “Word” for September. functions as this is what Glen would have wanted…..very sad loss and at a young and August didn’t start too well with the tender age….God Bless Glen xx. Branch loosing Glen Sharp after a long battle with MND (Motor Neuron Dis- The next function is the Ladies night ease), Glen and Ian have been avid sup- Dinner Dance in the Abbey House Hotel porters of our Branch functions for as and Colin Hutchinson will hopefully long as I can remember and a good ensure that the list will be available for the turnout from the Branch was welcomed, September meeting, so plan ahead and get Barrow Submariner’s Association Branch Officials HON CHAIRMAN TREASURER SOCIAL TEAM STANDARD WELFARE PRESIDENT Dave Barlow Mick Mailey Colin Hutchinson BEARERS COMMITTEE John V. Hart 01229 831196 01229 821290 01229 208604 Pedlar Palmer Michael Mailey 01229 821831 Ginge Cundall Alan Jones VICE CHAIRMAN LAY SECRETARY WEB MASTER Jeff Thomas NEWSLETTER CHAPLAIN Ken Collins Ron Hiseman Ron Hiseman 01229 464493 EDITOR Richard Britten Alan Jones 01229 823454 01229828664 01229 828664 01229 463150 01229 820265 Contents: 2)Submariner Shortage 3) HMS Upholder 4) RN Sub Museum 5) Chaplains Dit 6) CO Ambush 7) Ambush Pics 8) Old Navy 9) Obits 10) General Info 11) Quiz page September 2012 your names down, it was a great There are innumerable Associa- function last year and for those tions with a dazzling array of who did not attend it promises possible routes to follow but no Submariner to be a good function again. -

Thanks a Million, Tornado

Aug 11 Issue 39 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Thanks a million, Tornado Fast jets in focus − Typhoon and Tornado impress See inside Welcome Warrior Goliath’s The future Warfare goes Voyager returns to war giant task is now on screen lockheedmartin.com/f35 NOT JUSTAN AIRCRAFT, THE UK’SAIRCRAFT The F-35 Lightning II isn’t just a cutting-edge aircraft. It also demonstrates the power of collaboration. Today, a host of UK companies are playing their part in developing and building this next-generation F-35 fi ghter. The F-35 programme is creating thousands of jobs throughout the country, as well as contributing LIGHTNINGLIGHTNING IIII to UK industrial and economic development. It’s enhancing the UK’s ability to compete in the global technology marketplace. F-35 Lightning II. Delivering prosperity and security. UNITED KINGDOM THE F-35 LIGHTNING II TEAM NORTHROP GRUMMAN BAE SYSTEMS PRATT & WHITNEY LOCKHEED MARTIN 301-61505_NotJust_Desider.indd 1 7/14/11 2:12 PM FRONTISPIECE 3 lockheedmartin.com/f35 Jackal helps keep the peace JACKAL CUTS a dash on Highway 1 between Kabul and Kandahar, one of the most important routes in Afghanistan. Soldiers from the 9th/12th Royal Lancers have been helping to keep open a section of the road which locals use to transport anything from camels to cars. The men from the Lancers have the tough task of keeping the highway open along with members of 2 Kandak of the Afghan National Army, who man checkpoints along the road. NOT JUSTAN AIRCRAFT, Picture: Sergeant Alison Baskerville, Royal Logistic Corps THE UK’SAIRCRAFT The F-35 Lightning II isn’t just a cutting-edge aircraft. -

Trouble Ahead: Risks and Rising Costs in the UK Nuclear Weapons

TROUBLE AHEAD RISKS AND RISING COSTS IN THE UK NUCLEAR WEAPONS PROGRAMME TROUBLE AHEAD RISKS AND RISING COSTS IN THE UK NUCLEAR WEAPONS PROGRAMME David Cullen Nuclear Information Service April 2019 1 A note on terminology The National Audit Ofce (NAO) uses the term The terms ‘project’ and ‘programme’ are both used ‘Defence Nuclear Enterprise’. This refers to all of within government in diferent contexts to describe the elements in the programme but also includes the same thing. Although referred to as ‘projects’ elements which are technically and bureaucratically in the annual data produced by the government’s intertwined with it as part of the Astute submarine Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA), the programme. The term has also been adopted by the large MOD projects discussed in this report refer to MOD in recent publications. This report will also themselves as ‘programmes’ in their titles, and contain employ the term with the same meaning, usually within them major streams of work which are no doubt preferring the shorter ‘the Enterprise’. managed as separate projects in their own right. This report also uses the NATO shorthand ‘SSBN’ to As a general rule, this report aims to use the terms refer to submarines which are nuclear powered and project and programme to mean diferent things – a nuclear-armed and ‘SSN’ to refer to submarines which project being a relatively streamlined body of work are nuclear powered but not nuclear-armed. with a single purpose, and a programme being a larger-scale endeavour potentially encompassing A full glossary of terms and acronyms can be found at several bodies of work which may themselves be the end of the report on page 53. -

Desider April 2013 Issue 59

Apr 2013 Issue 59 desthe magazine for defencidere equipment and support A400M Atlas training boost Latest on the Materiel Strategy See inside Gunners hit Bridging Quick on Clyde Gold Cup the target the gap the draw on patrol drama Getting connected is now Together we are a new global IT and business services champion Delivering Information Enabled Capability Consulting, systems integration and outsourcing services Over 70,000 professionals in 40 countries Local knowledge, global strength cgi-group.co.uk Experience the commitment® LOGICA CGI - DESIDER FULL PAGE 210mm x 297 mm ARTWORK.indd 1 11/03/2013 17:02 FEATURES 20 een 20 Mapping out an Atlas future DE&S is investing £226 million on a specialist training school at RAF Brize Norton where the fleet of new A400M transport aircraft – named as Atlas by the RAF – will be based. The UK is buying 22 to replace the C-130 Hercules e: Sgt Nige Gr Pictur 22 Quick on the draw DE&S introduced a small radio to address an urgent ISAF need for secure ground-to-air communications. A team at DE&S has since developed the radio to fill a multitude of roles including satellite access for dismounted patrols 24 Now is the time to get serious Chief of Defence Materiel Bernard Gray has told a major conference that Nato members, including the UK, will not be able to sustain their Armed Forces if they do not seize the opportunity to work in a new, radical way 26 Keeping gunners on target cover image Technology to enhance weapon sights and make life easier 2013 and safer for gunners and commanders on the front line Aircrew and those who will work on the ground on the has been unveiled to stakeholders in a demonstration on the RAF’s next generation airlifter, the A400M, named by Lulworth Ranges in Dorset the service as Atlas, will be working on simulators to be APRIL installed at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire. -

Defence Acquisition

Defence acquisition Alex Wild and Elizabeth Oakes 17th May 2016 He efficient procurement of defence equipment has long been a challenge for British governments. It is an extremely complex process that is yet to be mastered with vast T sums of money invariably at stake – procurement and support of military equipment consumes around 40 per cent of annual defence cash expenditure1. In 2013-14 Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S) spent £13.9bn buying and supporting military equipment2. With the House of Commons set to vote on the “Main Gate” decision to replace Trident in 2016, the government is set to embark on what will probably be the last major acquisition programme in the current round of the Royal Navy’s post-Cold War modernisation strategy. It’s crucial that the errors of the past are not repeated. Introduction There has been no shortage of reports from the likes of the National Audit Office and the Public Accounts Committee on the subject of defence acquisition. By 2010 a £38bn gap had opened up between the equipment programme and the defence budget. £1.5bn was being lost annually due to poor skills and management, the failure to make strategic investment decisions due to blurred roles and accountabilities and delays to projects3. In 2008, the then Secretary of State for Defence, John Hutton, commissioned Bernard Gray to produce a review of defence acquisition. The findings were published in October 2009. The following criticisms of the procurement process were made4: 1 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120913104443/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/78821960-14A0-429E- A90A-FA2A8C292C84/0/ReviewAcquisitionGrayreport.pdf 2 https://www.nao.org.uk/report/reforming-defence-acquisition-2015/ 3 https://www.nao.org.uk/report/reforming-defence-acquisition-2015/ 4 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120913104443/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/78821960-14A0-429E- A90A-FA2A8C292C84/0/ReviewAcquisitionGrayreport.pdf 1 [email protected] Too many types of equipment are ordered for too large a range of tasks at too high a specification. -

SP's Naval Forces August-September 2010

august-September l 2010 Volume 5 No 4 `100.00 (India-based Buyer only) SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION www.spsnavalforces.net ROUNDUP 3 PaGe lead story Keeping an Eye submarines have progressed from having to porpoise at the surface to see outside through crude viewing devices fixed in height and direction to today’s photonic masts using high-resolution cameras housed in the sub - marine’s dorsal fin-like sail The Road Ahead Lt General (Retd) Naresh Chand The prospect of carrier-borne aircraft and military aviation, except unmanned PaGe 5 aerial vehicles, appears uncertain. It depends heavily on two factors—technology Crying Over Spilled Oil and economics. PhotograPhS: Indian Navy any spill, however small, has an environmen - tal and financial impact which takes time and resources to overcome Lt General (Retd) Naresh Chand PaGe 8 Weapons Under Water a modern torpedo can destroy targets at a range of 40 km and a speed of about 50 Sea Harriers on flight deck of INS Viraat knots. Its destructive power is more than a missile and it can differentiate between a tar - n ADMIRAL (RETD) ARUN PRAKASH explore a bit of aviation history first. or two seaplanes as a standard fit. They get and a decoy. a few months from now, on november would be launched from a ramp on the gun rysTal gazIng or predicting the 10, 2010, we will observe the centennial of turret and recovered on board by crane. Lt General (Retd) Naresh Chand future must be one of the most Eugene Ely’s intrepid demonstration that seaplanes being limited in perform - hazardous occupations known to aircraft could be operated from the deck ance, naval commanders began to demand PaGe 12 man. -

60 Years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 - 2018 Part 4: Europe & Canada Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 4: Europe & Canada. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States - Submarines Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications. -

2009 10 Gunline

Gunline Sept09.qxd:Gunline 28/9/09 15:48 Page 1 Gunline - The First Point of Contact Published by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Service October 2009 www.rfa.mod.uk FORT GEORGE IN MONTSERRAT FA Fort George visited ship’s own boats took the food ashore, Montserrat from 15th -20th along with an advance party of helpers. RJuly 2009. On Saturday 18th The remainder followed on local liberty July the ship hosted a BBQ ashore boats. The children had a fantastic time. for 20 children with special needs, At one stage during the afternoon I including several members of the counted more than 70 of the ship’s island’s very successful Special company at the cricket ground, Olympics team. The BBQ was held including the Commanding Officer and at the island’s cricket ground and Chief Engineer which help to produce a was followed by a 20/20 Cricket tremendous atmosphere.” match. The cricket proved a challenge too DSTO(N) Rhodes, the Visit far, though it was definitely a day when Liaison Officer, paid tribute to the the game mattered more than the result. ship’s company for their efforts. No fewer than 14 members of the ship’s “There is no doubt that the 30 people company took part against what was a Right: Gregory Willcock, who went ashore to assist with the powerful batting and bowling side. But President of the Montserrat BBQ were great ambassadors for the they stuck to their task and whilst they Cricket Association with his RFA. It is not easy to host an event were never going to win, they tried their daughter Keanna Meade, after like this from an anchorage but best from first ball to last. -

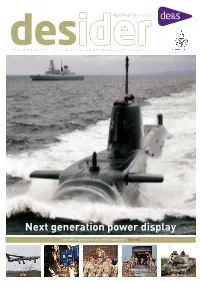

Next Generation Power Display

Apr/May 10 Issue 24 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Next generation power display Latest DE&S organisation chart and PACE supplement See inside Parc Chain Dress for Welcome Keeping life gang success home on track Picture: BAE Systems NEWS 5 4 Keeping on track Armoured vehicles in Afghanistan will be kept on track after DE&S extended the contract to provide metal tracks the vehicles run on. 8 UK Apache proves its worth The UK Apache attack helicopter fleet has reached the landmark of 20,000 flying hours in support of Operation Herrick 8 Just what the doctor ordered! DE&S’ Chief Operating Officer has visited the 2010 y Nimrod MRA4 programme at Woodford and has A given the aircraft the thumbs up after a flight. /M 13 Triumph makes T-boat history The final refit and refuel on a Trafalgar class nuclear submarine has been completed in Devonport, a pril four-year programme of work costing £300 million. A 17 Transport will make UK forces agile New equipment trailers are ready for tank transporter units on the front line to enable tracked vehicles to cope better with difficult terrain. 20 Enhancement to a soldier’s ‘black bag’ Troops in Afghanistan will receive a boost to their personal kit this spring with the introduction of cover image innovative quick-drying towels and head torches. 22 New system is now operational Astute and Dauntless, two of the most advanced naval A new command system which is central to the ship’s fighting capability against all kinds of threats vessels in the world, are pictured together for the first time is now operational on a Royal Navy Type 23 frigate. -

Devonport Naval Base's Nuclear Role

Devonport naval base’s CND nuclear role Her Majesty’s Naval Base Devonport, in the middle of the city of Plymouth, is where the United Kingdom’s submarines – including those armed with Trident missiles and nuclear warheads – undergo refuelling of their nuclear reactors and refurbishment of their systems. This work has potentially hazardous consequences, and the nuclear site has a history of significant accidents involving radioactive discharges. LL of Britain’s submarines are nuclear- both there and in Devonport. Submarines will be powered and the four Vanguard-class defueled before the dismantling process begins. Asubmarines carry the UK’s nuclear weapons Defueling is the most dangerous operation of the system, Trident. One dock at Devonport is entire decommissioning process. specifically designed to maintain these nuclear weapons submarines. Other docks are used to store Radioactive Reactor Pressure Vessels (each the size nuclear submarines that have been decommissioned of two double-decker buses and weighing around and await having their nuclear reactors removed and 750 tonnes) will be removed from the nuclear- the radioactive metals and components dismantled powered submarines at both Devonport and and sent as nuclear waste for storage. Rosyth dockyards and stored intact at Capenhurst, prior to disposal in a planned – but as yet non- In 2013 the Ministry of Defence confirmed that existent – Geological Disposal Facility. The Devonport is one of two sites in the UK (the other Ministry of Defence (MoD) is yet to find a location is Rosyth in Fife) where decommissioned nuclear- for storing intermediate level radioactive waste, and powered submarines will be dismantled once a site is using storage facilities at Sellafield reprocessing for the waste has been identified. -

Ministry of Defence the United Kingdom's Future Nuclear Deterrent

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The United Kingdom’s Future Nuclear Deterrent Capability REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL | HC 1115 Session 2007-2008 | 5 November 2008 The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending on behalf of Parliament. The Comptroller and Auditor General, Tim Burr, is an Officer of the House of Commons. He is the head of the National Audit Office which employs some 850 staff. He and the National Audit Office are totally independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of all Government departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to report to Parliament on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies have used their resources. Our work saves the taxpayer millions of pounds every year: at least £9 for every £1 spent running the Office. MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The United Kingdom’s Future Nuclear Deterrent Capability Ordered by the LONDON: The Stationery Office House of Commons £14.35 to be printed on 3 November 2008 REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL | HC 1115 Session 2007-2008 | 5 November 2008 This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act. Tim Burr Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 28 October 2008 The National Audit Office study team consisted of: Tom McDonald, Gareth Tuck, Helen Mullinger and James Fraser, under the direction of Tim Banfield This report can be found on the National Audit