Confronting an "Axis of Cyber"? China, Iran, North Korea, Russia in Cyberspace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Cyberwarfare Ethics As It Pertains to Civilian Computer Networks/Infrastructures

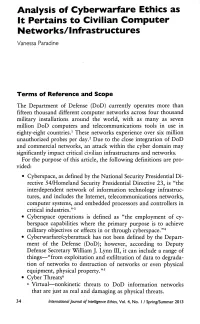

Analysis of Cyberwarfare Ethics as It Pertains to Civilian Computer Networks/Infrastructures Vanessa Paradine Terms of Reference and Scope The Department of Defense (DoD) currently operates more than fifteen thousand different computer networks across four thousand military installations around the world, with as many as seven million DoD computers and telecommunications tools in use in eighty-eight countries.1 These networks experience over six million unauthorized probes per day.2 Due to the close integration of DoD and commercial networks, an attack within the cyber domain may significantly impact critical civilian infrastructures and networks. For the purpose of this article, the following definitions are pro vided: • Cyberspace, as defined by the National Security Presidential Di rective 541H0meland Security Presidential Directive 23, is "the interdependent network of information technology infrastruc tures, and includes the Internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers in critical industries."3 • Cyberspace operations is defined as "the employment of cy berspace capabilities where the primary purpose is to achieve military objectives or effects in or through cyberspace."4 • Cyberwarfare/cyberattack has not been defined by the Depart ment of the Defense (DoD); however, according to Deputy Defense Secretary William J. Lynn III, it can include a range of things-"from exploitation and exfiltration of data to degrada tion of networks to destruction of networks or even physical equipment, physical property."5 • Cyber Threats6 o Virtual-nonkinetic threats to DoD information networks that are just as real and damaging as physical threats. 34 Internatianal Journal of Intelligence Ethics, Vol. 4, No. 1 / Spring/Summer 2013 Analysis of Cyberwarfare Ethics 35 o Physical-kinetic threats mixed with nonkinetic threats; can severely impact the effectiveness of military joint operations. -

The Emigrant's Directory to the Western States of North America

Library of Congress The emigrant's directory to the western states of North America; including a voyage out from Liverpool; the geography and topography of the whole western country, according to its latest improvemtnes; with instructions for descending the rivers Ohio and Mississippi, also, a brief account of a new British settlement on the headwaters of the Susquehanna, in Philadelphia [_] By William Amphlett. THE EMIGRANT's DIRECTORY TO THE WESTERN STATES OF NORTH AMERICA; INCLUDING A VOYAGE OUT FROM LIVERPOOL; THE GEOGRAPHY AND TOPOGRAPHY OF THE WHOLE Western Country According to its latest Improvements; WITH INSTRUCTIONS FOR DESCENDING THE RIVERS OHIO AND MISSISSIPPI; ALSO, A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF A NEW BRITISH SETTLEMENT ON THE HEAD- WATERS OF THE SUSQUEHANNA, IN PHILADELPHIA. BY WILLIAM AMPHLETT, FORMERLY OF LONDON AND LATE OF THE COUNTY OF SALOP, NOW PRESIDENT ON THE BANKS OF THE OHIO RIVER. LONDON: PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, AND BROWN, PATERNOSTER-ROW. 1819. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 33441 '03 The emigrant's directory to the western states of North America; including a voyage out from Liverpool; the geography and topography of the whole western country, according to its latest improvemtnes; with instructions for descending the rivers Ohio and Mississippi, also, a brief account of a new British settlement on the headwaters of the Susquehanna, in Philadelphia [_] By William Amphlett. http:// www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.16092 Library of Congress Printed by Strahan and Spottiswoode, Printers-Stree, London. TO MY FIRST FRIEND, THE FRIEND OF MY YOUTH AND MY HAPPIEST DAYS; TO HENRI BYNNER, Esq. OF TRIESTE, IN THE AUSTRIAN DOMINIONS, I DEDICATE THESE FEW PAGES. -

Xbt.Doc.248.2.Pdf

MAY 25, 2018 United States District Court Southern District of Florida Miami Division CASE NO. 1:17-CV-60426-UU ALEKSEJ GUBAREV, XBT HOLDING S.A., AND WEBZILLA, INC., PLAINTIFFS, VS BUZZFEED, INC. AND BEN SMITH, DEFENDANTS Expert report of Anthony J. Ferrante FTI Consulting, Inc. 4827-3935-4214v.1 0100812-000009 Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Qualifications ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Scope of Assignment ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Glossary of Important Terms ............................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Technical Investigation ................................................................................................................................ 8 Investigative Findings ....................................................................................................................................... -

Attribution and Response to Cybercrime/Terrorism/Warfare Susan W

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 97 Article 2 Issue 2 Winter Winter 2007 At Light Speed: Attribution and Response to Cybercrime/Terrorism/Warfare Susan W. Brenner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Susan W. Brenner, At Light Speed: Attribution and Response to Cybercrime/Terrorism/Warfare, 97 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 379 (2006-2007) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/07/9702-0379 THE JOURNALOF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 97. No. 2 Copyright 0 2007 by NorthwesternUniversity. Schoolof Low Printedin U.S.A. "AT LIGHT SPEED": ATTRIBUTION AND RESPONSE TO CYBERCRIME/TERRORISM/WARFARE SUSAN W. BRENNER* This Article explains why and how computer technology complicates the related processes of identifying internal (crime and terrorism) and external (war) threats to social order of respondingto those threats. First, it divides the process-attribution-intotwo categories: what-attribution (what kind of attack is this?) and who-attribution (who is responsiblefor this attack?). Then, it analyzes, in detail, how and why our adversaries' use of computer technology blurs the distinctions between what is now cybercrime, cyberterrorism, and cyberwarfare. The Article goes on to analyze how and why computer technology and the blurring of these distinctions erode our ability to mount an effective response to threats of either type. -

Hospital Ships in the War on Terror Richard J

Naval War College Review Volume 58 Article 6 Number 1 Winter 2005 Hospital Ships in the War on Terror Richard J. Grunawalt Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Grunawalt, Richard J. (2005) "Hospital Ships in the War on Terror," Naval War College Review: Vol. 58 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol58/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grunawalt: Hospital Ships in the War on Terror Professor Grunawalt, professor emeritus of the Naval War College, is the former director of the Oceans Law and Policy Department of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies. His publications include (with John E. King and Ronald S. McClain) Protection of the Environ- ment during Armed Conflict (1996) and Targeting Enemy Merchant Shipping (1993)—volumes 69 and 65 of the Naval War College International Law Studies Series. Naval War College Review, Winter 2005, Vol. 58, No. 1 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2005 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 58 [2005], No. 1, Art. 6 HOSPITAL SHIPS IN THE WAR ON TERROR Sanctuaries or Targets? Richard J. Grunawalt mployment of military hospital ships in support of the war on terror is mili- Etarily, politically, and morally appropriate. -

Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code RL31339 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: U.S. Efforts to Change the Regime Updated August 16, 2002 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: U.S. Efforts to Change the Regime Summary In his January 29, 2002 State of the Union message, President Bush characterized Iraq as part of an “axis of evil,” along with Iran and North Korea. The President identified the key threat from Iraq as its development of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and the potential for Iraq to transfer WMD to the terrorist groups it sponsors. In recent statements, the President and other senior officials have said the United States needs to ensure that Saddam Husayn cannot be positioned to pose a major and imminent threat to U.S. national security. The President’s subsequent statements have left observers with the clear implication that the Administration is leaning toward military action to achieve the ouster of Iraq’s President Saddam Husayn and his Ba’th Party regime, although the President says no decision has been made on the means of achieving regime change. Regime change has been official U.S. policy since October 1998. Even before that, U.S. efforts to oust Saddam have been pursued, with varying degrees of intensity, since the end of the Gulf war in 1991. These efforts primarily involved U.S. backing for opposition groups inside and outside Iraq. According to several experts, past efforts to change the regime floundered because of limited U.S. -

Jude Akuwudike

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Jude Akuwudike Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company Delroy Grant (The Night MANHUNT Marc Evans ITV Studios Stalker) PLEBS Agrippa Sam Leifer Rise Films/ITV2 MOVING ON Dr Bello Jodhi May LA Productions/BBC THE FORGIVING EARTH Dr Busasa Hugo Blick BBC/Netflix CAROL AND VINNIE Ernie Dan Zeff BBC IN THE LONG RUN Uncle Akie Declan Lowney Sky KIRI Reverend Lipede Euros Lyn Hulu/Channel 4 THE A WORD Vincent Sue Tully Fifty Fathoms/BBC DEATH IN PARADISE Series 6 Tony Simon Delaney Red Planet/BBC CHEWING GUM Series 2 Alex Simon Neal Retort/E4 FRIDAY NIGHT DINNER Series 4 Custody Sergeant Martin Dennis Channel 4 FORTITUDE Series 2 & 3 Doctor Adebimpe Hettie Macdonald Tiger Aspect/Sky Atlantic LUCKY MAN Doctor Marghai Brian Kelly Carnival Films/Sky 1 UNDERCOVER Al James Hawes BBC CUCUMBER Ralph Alice Troughton Channel 4 LAW & ORDER: UK Marcus Wright Andy Goddard Kudos Productions HOLBY CITY Marvin Stewart Fraser Macdonald BBC Between Us (pty) Ltd/Precious THE NO.1 LADIES DETECTIVE AGENCY Oswald Ranta Charles Sturridge Films MOSES JONES Matthias Michael Offer BBC SILENT WITNESS Series 11 Willi Brendan Maher BBC BAD GIRLS Series 7 Leroy Julian Holmes Shed Productions for ITV THE LAST DETECTIVE Series 3 Lemford Bradshaw David Tucker Granada HOLBY CITY Derek Fletcher BBC ULTIMATE FORCE Series 2 Mr Salmon ITV SILENT WITNESS: RUNNING ON -

In Defense of Cyberterrorism: an Argument for Anticipating Cyber-Attacks

IN DEFENSE OF CYBERTERRORISM: AN ARGUMENT FOR ANTICIPATING CYBER-ATTACKS Susan W. Brenner Marc D. Goodman The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States brought the notion of terrorism as a clear and present danger into the consciousness of the American people. In order to predict what might follow these shocking attacks, it is necessary to examine the ideologies and motives of their perpetrators, and the methodologies that terrorists utilize. The focus of this article is on how Al-Qa'ida and other Islamic fundamentalist groups can use cyberspace and technology to continue to wage war againstthe United States, its allies and its foreign interests. Contending that cyberspace will become an increasingly essential terrorist tool, the author examines four key issues surrounding cyberterrorism. The first is a survey of conventional methods of "physical" terrorism, and their inherent shortcomings. Next, a discussion of cyberspace reveals its potential advantages as a secure, borderless, anonymous, and structured delivery method for terrorism. Third, the author offers several cyberterrorism scenarios. Relating several examples of both actual and potential syntactic and semantic attacks, instigated individually or in combination, the author conveys their damagingpolitical and economic impact. Finally, the author addresses the inevitable inquiry into why cyberspace has not been used to its full potential by would-be terrorists. Separately considering foreign and domestic terrorists, it becomes evident that the aims of terrorists must shift from the gross infliction of panic, death and destruction to the crippling of key information systems before cyberattacks will take precedence over physical attacks. However, given that terrorist groups such as Al Qa'ida are highly intelligent, well-funded, and globally coordinated, the possibility of attacks via cyberspace should make America increasingly vigilant. -

Iran's Gray Zone Strategy

Iran’s Gray Zone Strategy Cornerstone of its Asymmetric Way of War By Michael Eisenstadt* ince the creation of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Iran has distinguished itself (along with Russia and China) as one of the world’s foremost “gray zone” actors.1 For nearly four decades, however, the United States has struggled to respond effectively to this asymmetric “way of war.” Washington has often Streated Tehran with caution and granted it significant leeway in the conduct of its gray zone activities due to fears that U.S. pushback would lead to “all-out” war—fears that the Islamic Republic actively encourages. Yet, the very purpose of this modus operandi is to enable Iran to pursue its interests and advance its anti-status quo agenda while avoiding escalation that could lead to a wider conflict. Because of the potentially high costs of war—especially in a proliferated world—gray zone conflicts are likely to become increasingly common in the years to come. For this reason, it is more important than ever for the United States to understand the logic underpinning these types of activities, in all their manifestations. Gray Zone, Asymmetric, and Hybrid “Ways of War” in Iran’s Strategy Gray zone warfare, asymmetric warfare, and hybrid warfare are terms that are often used interchangeably, but they refer neither to discrete forms of warfare, nor should they be used interchangeably—as they often (incor- rectly) are. Rather, these terms refer to that aspect of strategy that concerns how states employ ways and means to achieve national security policy ends.2 Means refer to the diplomatic, informational, military, economic, and cyber instruments of national power; ways describe how these means are employed to achieve the ends of strategy. -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

Prism Vol. 9, No. 2 Prism About Vol

2 021 PRISMVOL. 9, NO. 2 | 2021 PRISM VOL. 9, NO. 2 NO. 9, VOL. THE JOURNAL OF COMPLEX OPER ATIONS PRISM ABOUT VOL. 9, NO. 2, 2021 PRISM, the quarterly journal of complex operations published at National Defense University (NDU), aims to illuminate and provoke debate on whole-of-government EDITOR IN CHIEF efforts to conduct reconstruction, stabilization, counterinsurgency, and irregular Mr. Michael Miklaucic warfare operations. Since the inaugural issue of PRISM in 2010, our readership has expanded to include more than 10,000 officials, servicemen and women, and practi- tioners from across the diplomatic, defense, and development communities in more COPYEDITOR than 80 countries. Ms. Andrea L. Connell PRISM is published with support from NDU’s Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS). In 1984, Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger established INSS EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS within NDU as a focal point for analysis of critical national security policy and Ms. Taylor Buck defense strategy issues. Today INSS conducts research in support of academic and Ms. Amanda Dawkins leadership programs at NDU; provides strategic support to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, combatant commands, and armed services; Ms. Alexandra Fabre de la Grange and engages with the broader national and international security communities. Ms. Julia Humphrey COMMUNICATIONS INTERNET PUBLICATIONS PRISM welcomes unsolicited manuscripts from policymakers, practitioners, and EDITOR scholars, particularly those that present emerging thought, best practices, or train- Ms. Joanna E. Seich ing and education innovations. Publication threshold for articles and critiques varies but is largely determined by topical relevance, continuing education for national and DESIGN international security professionals, scholarly standards of argumentation, quality of Mr. -

Cyber-Conflict Between the United States of America and Russia CSS

CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECT Hotspot Analysis: Cyber-conflict between the United States of America and Russia Zürich, June 2017 Version 1 Risk and Resilience Team Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich Cyber-conflict between the United States of America and Russia Authors: Marie Baezner, Patrice Robin © 2017 Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich Contact: Center for Security Studies Haldeneggsteig 4 ETH Zürich CH-8092 Zurich Switzerland Tel.: +41-44-632 40 25 [email protected] www.css.ethz.ch Analysis prepared by: Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich ETH-CSS project management: Tim Prior, Head of the Risk and Resilience Research Group; Myriam Dunn Cavelty, Deputy Head for Research and Teaching; Andreas Wenger, Director of the CSS Disclaimer: The opinions presented in this study exclusively reflect the authors’ views. Please cite as: Baezner, Marie; Robin, Patrice (2017): Hotspot Analysis: Cyber-conflict between the United States of America and Russia, June 2017, Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich. 2 Cyber-conflict between the United States of America and Russia Table of Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Background and chronology 6 3 Description 9 3.1 Tools and techniques 9 3.2 Targets 10 3.3 Attribution and actors 10 4 Effects 11 4.1 Social and internal political effects 11 4.2 Economic effects 13 4.3 Technological effects 13 4.4 International effects 13 5 Consequences 14 5.1 Improvement of cybersecurity 14 5.2 Raising awareness of propaganda and misinformation 15 5.3 Observation of the evolution of relations between the USA and Russia 15 5.4 Promotion of Confidence Building Measures 16 6 Annex 1 17 7 Glossary 18 8 Abbreviations 19 9 Bibliography 19 3 Cyber-conflict between the United States of America and Russia Executive Summary Effects Targets: US State institutions and a political The analysis found that the tensions between the party.