CONGO, Republic of The.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

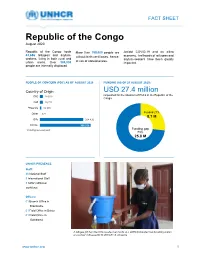

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Reconstruction Under Fire: Case Studies and Further Analysis Of

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Reconstruction Under Fire Case Studies and Further Analysis of Civil Requirements A COMPANION VOLUME TO RECONSTRUCTION UNDER FIRE: UNIFYING CIVIL AND MILITARY COUNTERINSURGENCY Brooke Stearns Lawson, Terrence K. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Repupublic of Congo

BE TOU & IMPFONDO MARKET ASSESSMENT IN LIKOUALA – REPUBLIC OF CONGO Cash Based Transfer Market This market assessment assesses the feasibility of markets in Bétou and Assessment: Impfondo to absorb and respond to a CBT intervention aimed at supporting CAR refugees’ food security in The Republic of Congo’s Likouala region. The December report explores appropriate measures a CBT intervention in Likouala would 2015 need to adopt in order to address hurdles limiting Bétou and Impfondo markets’ functionality. Contents Executive Summary: ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Introduction and Macro-Economic Analysis of RoC .............................................................. 5 1.1: Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2: The Economy ................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 2: Market Assessment Introduction and Methodology ............................................................. 9 2.1: Market Assessment Introduction .................................................................................................... 9 2.2: Market Assessment Methodology ................................................................................................... 9 Section 3: Limitations of the Market Assessment ............................................................................... -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

WFP Republic of Congo Country Brief May 2021

WFP Republic of Congo In Numbers Country Brief 549.9 mt food assistance distributed May 2021 314,813 US$ cash-based transfers made US$ 13.5 million six-month (June 2021 – November 2021) net funding requirements 128,312 people assisted 52% 48% in May 2021 Operational Updates Operational Context • As part of the Joint SDG Fund Programme, implemented by WFP, UNICEF, and WHO, an advocacy The Republic of Congo (RoC) ranks poorly on the Human workshop for implementing the law n°5-2011 on the Development Index. Its food production is below national promotion and protection of indigenous peoples' requirements, with only 2 percent of arable land currently rights was held in Brazzaville. under cultivation, covering 30 percent of the country’s • The Mbala Pinda project was awarded by the WFP food needs. Forty-eight percent of Congolese live on less Innovation Accelerator with US$ 100,000. This funding than USD 1.25 per day. will allow implementing capacity strengthening WFP is assisting 61,000 people affected by catastrophic activities of 16 women producers' groups producing flooding, which took place two years in a row, with high the local cassava and peanut-based snack "Mbala negative impacts on food security and livelihoods. Pinda". This project will contribute to their Vulnerability assessments show that between 36 and 79 empowerment, enhance their productivity, and percent of the population is moderately or severely food identify new market opportunities. insecure. Sustained food assistance is needed in order to • WFP received US$ 1.8 million from the German Federal avoid a full-blown food crisis in affected areas. -

MYR 2010 Roc SCREEN.Pdf

SAMPLE OF ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEALS ACF GOAL Malteser TEARFUND ACTED GTZ Medair Terre des Hommes ADRA Handicap International Mercy Corps UNAIDS AVSI HELP MERLIN UNDP CARE HelpAge International NPA UNDSS CARITAS Humedica NRC UNESCO CONCERN IMC OCHA UNFPA COOPI INTERSOS OHCHR UN-HABITAT CRS IOM OXFAM UNHCR CWS IRC Première Urgence UNICEF DRC IRIN Save the Children WFP FAO Islamic Relief Worldwide Solidarités WHO LWF World Vision International TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................. 1 Table I. Summary of requirements, commitments/contributions and pledges (grouped by sector)....... 3 Table II. Summary of requirements, commitments/contributions and pledges (grouped by appealing organization) ............................................................................................................................ 3 2. CHANGES IN CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ....................................................... 4 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS ............... 5 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................. 5 3.2 SECTOR RESPONSE PLANS ......................................................................................................................... 6 Food....................................................................................................................................................... -

Republic of the Congo 2012 Human Rights Report

REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 2012 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Republic of the Congo is a parliamentary republic in which the constitution vests most of the decision-making authority and political power in the president and his administration. Denis Sassou-N’Guesso was reelected president in 2009 with 78 percent of the vote, but opposition candidates and domestic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) questioned the validity of this figure. The 2009 election was peaceful, and the African Union declared the elections free and fair; however, opposition candidates and NGOs cited irregularities. Legislative elections were held in July and August 2011 for 137 of the National Assembly’s 139 seats; elections could not be held in two electoral districts in Brazzaville because of the March 4 munitions depot explosions in the capital’s Mpila neighborhood. The African Union declared the elections free, fair, and credible, while still citing numerous irregularities. Civil society election observers estimated the participation rate for the legislative elections at 10 to15 percent nationwide. While the country has a multiparty political system, members of the president’s Congolese Labor Party (PCT) and its allies won 95 percent of the legislative seats and occupied most senior government positions. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. The government generally maintained effective control over the security forces; however, there some members of the security forces acted independently of government authority, committed abuses, and engaged -

UNICF Humanitarian Action 2010

Contents UNICEF HUMANITARIAN ACTION FUNDING STATUS AS PER MID-YEAR REVIEW ...................................................................... 4 HUMANITARIAN ACTION REPORT MID-YEAR REVIEW ..................................................................................... 5 GLOBAL SUPPORT FOR HUMANITARIAN ACTION ........................................................................................... 14 EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA ................................................................................................................. 17 BURUNDI ......................................................................................................................................................... 20 ERITREA ........................................................................................................................................................... 23 ETHIOPIA ......................................................................................................................................................... 26 KENYA .............................................................................................................................................................. 29 MADAGASCAR ................................................................................................................................................. 32 SOMALIA .......................................................................................................................................................... 34 UGANDA ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Congo: Refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo

: Refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Mar 2010) Total Displacement Congo from Equateur since Oct 2009 114,000 60,000 17,000 Since October 2009, some 114,000 refugees have in Congo in DRC in Central fled armed clashes in Equateur Province in the African Republic Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and found refuge in the Congo.1 ang ub ui 1 Background O The Equateur Province has Douala CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC experienced sporadic Douala - Bangui Bangui Logistics inter-ethnic violence over the 7 days past several decades, The relief operation is generated by tensions over logistically complex and limited resources, circulation CAMEROON Sud-Ubangi expensive; the majority of district of small arms and weak sites can be reached only by 5 Bétou 2 Government presence.1 plane or boat. Likouala Dongo 4 Many boats are in 2 Recent clashes disrepair and fuel is EQUATORIAL 3 March 2009: Armed GUINEA scarce and costly. Due to low clashes arose from disputes water levels during the dry Impfondo Buburu Congo over farming and fishing season, the river is only rights in Sud-Ubangi district. suitable for small craft.1 1 Equateur Oct 2009: Fighting displaced 5 The road between Bétou people to other parts of and Impfondo is in poor Equateur, with an influx of condition and usable only DEMOCRATIC refugees in Central African Mbandaka during part of the dry REPUBLIC 1 Republic and the Congo. At GABON 4 season. Mbandaka - Impfondo OF THE CONGO least 270 civilians killed in 5 days Dongo. CONGO Disclaimer: Nov 2009: Civil unrest spread The boundaries and names shown Congo to a wider area in Equateur. -

Congo Basin Peatlands: Threats and Conservation Priorities

Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-017-9774-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Congo Basin peatlands: threats and conservation priorities Greta C. Dargie1,2,3 & Ian T. Lawson3 & Tim J. Rayden 4 & Lera Miles 5 & Edward T. A. Mitchard6 & Susan E. Page 7 & Yannick E. Bocko8 & Suspense A. Ifo9 & Simon L. Lewis1,2 Received: 11 August 2017 /Accepted: 3 December 2017 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract The recent publication of the first spatially explicit map of peatlands in the Cuvette Centrale, central Congo Basin, reveals it to be the most extensive tropical peatland complex, at ca. 145,500 km2. With an estimated 30.6 Pg of carbon stored in these peatlands, there are now questions about whether these carbon stocks are under threat and, if so, what can be done to protect them. Here, we analyse the potential threats to Congo Basin peat carbon stocks and identify knowledge gaps in relation to these threats, and to how the peatland systems might respond. Climate change emerges as a particularly pressing concern, given its potential to destabilise carbon stocks across the whole area. Socio-economic developments are increasing across central Africa and, whilst much of the peatland area is protected on paper by some form of conservation designation, the potential exists for hydrocarbon exploration, logging, plantations and other forms of disturbance to significantly damage the peatland ecosystems. The low level of human intervention at present suggests that the opportunity still exists to protect the peatlands in a largely intact state, possibly drawing on climate change mitigation * Greta C. -

Republic of Congo 2010

SAMPLE OF ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEALS ACF GOAL MACCA TEARFUND ACTED GTZ Malteser Terre des Hommes ADRA Handicap International Medair UNAIDS Afghanaid HELP Mercy Corps UNDP AVSI HelpAge International MERLIN UNDSS CARE Humedica NPA UNESCO CARITAS IMC NRC UNFPA CONCERN INTERSOS OCHA UN-HABITAT COOPI IOM OHCHR UNHCR CRS IRC OXFAM UNICEF CWS IRIN Première Urgence WFP DRC Islamic Relief Worldwide Save the Children WHO FAO LWF Solidarités World Vision International TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................. 1 Table I. Summary of requirements, commitments/contributions and pledges (grouped by sector)........... 3 Table II. Summary of requirements, commitments/contributions and pledges (grouped by appealing organization) ................................................................................................................................3 2. 2009 IN REVIEW............................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 CONTEXT................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 HUMANITARIAN ACHIEVEMENTS TO DATE AND LESSONS LEARNED..................................................................... 7 3. NEEDS ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................................................