Congo Basin Peatlands: Threats and Conservation Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Sources of Precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands Regionala Källor Till Nederbörden I Det Etiopiska Höglandet

Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2015: 2 Regional Sources of Precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands Regionala källor till nederbörden i det Etiopiska höglandet Elnaz Ashkriz DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2015: 2 Regional Sources of Precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands Regionala källor till nederbörden i det Etiopiska höglandet Elnaz Ashkriz Copyright © Elnaz Ashkriz and the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2015 Sammanfattning Regionala källor till nederbörden i det Etiopiska höglandet Elnaz Ashkriz Denna uppsats undersöker ursprunget till den stora mängd nederbörd som faller i det etiopiska höglandet. Med Moisture transport into the Ethiopian Highlands av Ellen Viste och Asgeir Sorteberg (2011) som grund syftar denna uppsats till att jämföra samma data men genom att titta på ett mycket kortare intervall för att se vad som försummas när undersökningar på större skalor utförs. Medan undersökningen av Viste och Sorteberg (2011) fokuserar på de två regnrikaste månaderna, juli och augusti under elva år, 1998-2008, så fokuserar denna uppsats enbart på juli år 2008. Syftet med denna uppsats var att se vart nederbörden till det Etiopiska höglandet kommer ifrån under juli månad 2008. För att undersöka detta så har man valt att titta på parametrar såsom horisontell- och vertikal vindriktning på olika höjder samt fukt- innehållet i dessa vindar. Som grund för undersökningen så har denna uppsats, likt Vistes och Sortebergs, använt ERA-Interim data. -

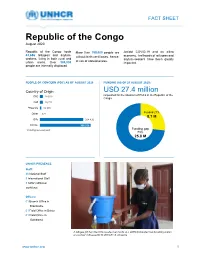

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Congo-Brazzaville) Minería Y Geología, Vol

Minería y Geología ISSN: 1993-8012 [email protected] Instituto Superior Minero Metalúrgico de Moa 'Dr Antonio Nuñez Jiménez' Cuba Impact of seasonal variability of precipitation on surface and groundwaters in the Mbe plateau in North Poll (Congo- Brazzaville) Obami-Ondon, Harmel; Ngouala-Mabonzo, Medard; Gampio-Mbilou, Urbain; Mabiala, Bernard Impact of seasonal variability of precipitation on surface and groundwaters in the Mbe plateau in North Poll (Congo-Brazzaville) Minería y Geología, vol. 36, no. 3, 2020 Instituto Superior Minero Metalúrgico de Moa 'Dr Antonio Nuñez Jiménez', Cuba Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=223563520007 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Minería y Geología, 2020, vol. 36, no. 3, Julio-Septiembre, ISSN: 1993-8012 Impact of seasonal variability of precipitation on surface and groundwaters in the Mbe plateau in North Poll (Congo-Brazzaville) Impacto de la variabilidad estacional de las precipitaciones sobre las aguas superficiales y subterráneas en la meseta de Mbe en North Pool (Congo-Brazzaville) Harmel Obami-Ondon Redalyc: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? Marien Ngouabi University, Congo id=223563520007 [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5205-1553 Medard Ngouala-Mabonzo Marien Ngouabi University, Congo http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6145-4477 Urbain Gampio-Mbilou Marien Ngouabi University, Congo http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7178-7168 Bernard Mabiala Marien Ngouabi University, Congo Received: 01 May 2020 Accepted: 01 June 2020 Resumen: Este estudio se enfoca en el impacto de la variabilidad estacional de la lluvia en la disponibilidad de agua de la meseta Mbé entre noviembre de 2017 y agosto de 2018. -

Reconstruction Under Fire: Case Studies and Further Analysis Of

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Reconstruction Under Fire Case Studies and Further Analysis of Civil Requirements A COMPANION VOLUME TO RECONSTRUCTION UNDER FIRE: UNIFYING CIVIL AND MILITARY COUNTERINSURGENCY Brooke Stearns Lawson, Terrence K. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Page 1 of 3 Minority Rights Group International : Congo : Congo Overview 7/21/2015

Minority Rights Group International : Congo : Congo Overview Page 1 of 3 Connect: World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples Home About us Contact us News Updates Directory › Africa › Congo › CONGO OVERVIEW { Environment { Peoples { History { Governance { Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment Straddling the equator, the Republic of Congo (Congo-Brazzaville) borders the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo-Kinshasa) in the south and east, the Central African Republic and Cameroon in the north, and Gabon in the west. In the south-west, the Congo borders the Cabinda exclave of Angola and the Atlantic Ocean. Congo is sparsely populated outside of southern urban centres; much of the north is swampland. Tropical climate and vegetation predominate, but the climate is drier and cooler towards the ocean. The Republic of Congo has offshore oil reserves. Peoples Main languages: Lingala, Koutouba or Kikongo, Téké, French (official) Main religions: indigenous beliefs, syncretic Christianity, Islam Minority groups include Bakongo 1.8 million (48%), Batéké 630,000 (17%), M’Boshi 445,000 (12%) and BaAka 7,000–15,000. [Note: Population percentages come from the 2006 CIA World Factbook, and are converted to numbers using the CIA estimate for total population of 3.7 million. For BaAka, Ethnologue estimates a population of 15,000 as of 1986] The largest ethnic cluster is Bakongo, constituting 48 per cent of the population. Traditionally cassava farmers and fishing people, Bakongo women in particular are noted (sometimes with animosity) for their enterprise in cash-cropping and especially in trade. They have stood out as assiduous organizers, especially in religion and politics. -

Empty Forests, Empty Stomachs? Bushmeat and Livelihoods in the Congo and Amazon Basins

International Forestry Review Vol.13(3), 2011 355 Empty forests, empty stomachs? Bushmeat and livelihoods in the Congo and Amazon Basins R. NASI1, A. TABER1 and N. VAN VLIET2 1Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Jalan CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor 16680, Indonesia 2Department of Geography and Geology, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark Email: [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] SUMMARY Protein from forest wildlife is crucial to rural food security and livelihoods across the tropics. The harvest of animals such as tapir, duikers, deer, pigs, peccaries, primates and larger rodents, birds and reptiles provides benefits to local people worth millions of US$ annually and represents around 6 million tonnes of animals extracted yearly. Vulnerability to hunting varies, with some species sustaining populations in heavily hunted secondary habitats, while others require intact forests with minimal harvesting to maintain healthy populations. Some species or groups have been characterized as ecosystem engineers and ecological keystone species. They affect plant distribution and structure ecosystems, through seed dispersal and predation, grazing, browsing, rooting and other mechanisms. Global attention has been drawn to their loss through debates regarding bushmeat, the “empty forest” syndrome and their ecological importance. However, information on the harvest remains fragmentary, along with understanding of ecological, socioeconomic and cultural dimensions. Here we assess the consequences, both for ecosystems and local livelihoods, of the loss of these species in the Amazon and Congo basins. Keywords: bushmeat, livelihoods, forest, Amazon, Congo Forêts vides, estomacs vides? Viande de brousse et condition de vie dans les bassins du Congo et de l’Amazone. -

Repupublic of Congo

BE TOU & IMPFONDO MARKET ASSESSMENT IN LIKOUALA – REPUBLIC OF CONGO Cash Based Transfer Market This market assessment assesses the feasibility of markets in Bétou and Assessment: Impfondo to absorb and respond to a CBT intervention aimed at supporting CAR refugees’ food security in The Republic of Congo’s Likouala region. The December report explores appropriate measures a CBT intervention in Likouala would 2015 need to adopt in order to address hurdles limiting Bétou and Impfondo markets’ functionality. Contents Executive Summary: ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Introduction and Macro-Economic Analysis of RoC .............................................................. 5 1.1: Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2: The Economy ................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 2: Market Assessment Introduction and Methodology ............................................................. 9 2.1: Market Assessment Introduction .................................................................................................... 9 2.2: Market Assessment Methodology ................................................................................................... 9 Section 3: Limitations of the Market Assessment ............................................................................... -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

The Making of Concessions: Traditional Authorities, Transnational

The Making of Concessions: Traditional Authorities, Transnational Capital, and Territorialized Identities in Africa By Rebecca Hardin Paper presented to the Environmental Politics Seminar UC Berkeley, April 27 2007 Draft: please do not cite, nor reproduce Note: This paper presents a framework I am developing for a book project tentatively entitled “Concessionary Cultures.” I am currently revising the project for the University of California Press series “Colonialisms.” The opportunity to benefit from the EP seminar discussion is very welcome. In developing this to date I have incurred intellectual debts to the following readers: Arun Agrawal, Susan E. Cook, Jane Guyer, Alain Karsenty, Damani Partridge, John Galaty, Nahomi Ichino, Eduardo Kohn, Nadine Naber, Devra Meuller, Abena Osseo-Assare, Lorraine Paterson, Beth Povinelli, Hugh Raffles, Jesse Ribot, Mary Steedly, Miriam Ticktin, Diana Wylie,and an anonymous reviewer for the University of California Press. The research support of McGill University, the University of Michigan, and the Harvard Academy of International and Area Studies has been crucial, 1 Nestled within the Dzanga Sangha Dense Forest Reserve and Dzanga Ndoki National Park, the small town of Bayanga is the largest settlement in that southernmost triangle of the Central African Republic (CAR) that borders Cameroon and the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville). The establishment (1988) and subsequent legislation (1991) of the Park and Reserve (which I’ll refer to at the RDS) created one of the last protected areas established in the CAR, and one of only two sizeable forest reserves in that country. Conducting research on the role of tourism and trophy hunting in the management of this protected area found me sitting one evening with a pair of professional trophy hunters over the cocktails they call “sundowners.” During their hunts with clients that week, they complained, they had found abundant evidence of poaching, and they feared that too many of the animal trophies they sought might be marred by scars from wire snares. -

WFP Republic of Congo Country Brief May 2021

WFP Republic of Congo In Numbers Country Brief 549.9 mt food assistance distributed May 2021 314,813 US$ cash-based transfers made US$ 13.5 million six-month (June 2021 – November 2021) net funding requirements 128,312 people assisted 52% 48% in May 2021 Operational Updates Operational Context • As part of the Joint SDG Fund Programme, implemented by WFP, UNICEF, and WHO, an advocacy The Republic of Congo (RoC) ranks poorly on the Human workshop for implementing the law n°5-2011 on the Development Index. Its food production is below national promotion and protection of indigenous peoples' requirements, with only 2 percent of arable land currently rights was held in Brazzaville. under cultivation, covering 30 percent of the country’s • The Mbala Pinda project was awarded by the WFP food needs. Forty-eight percent of Congolese live on less Innovation Accelerator with US$ 100,000. This funding than USD 1.25 per day. will allow implementing capacity strengthening WFP is assisting 61,000 people affected by catastrophic activities of 16 women producers' groups producing flooding, which took place two years in a row, with high the local cassava and peanut-based snack "Mbala negative impacts on food security and livelihoods. Pinda". This project will contribute to their Vulnerability assessments show that between 36 and 79 empowerment, enhance their productivity, and percent of the population is moderately or severely food identify new market opportunities. insecure. Sustained food assistance is needed in order to • WFP received US$ 1.8 million from the German Federal avoid a full-blown food crisis in affected areas. -

Living Under a Fluctuating Climate and a Drying Congo Basin

sustainability Article Living under a Fluctuating Climate and a Drying Congo Basin Denis Jean Sonwa 1,* , Mfochivé Oumarou Farikou 2, Gapia Martial 3 and Fiyo Losembe Félix 4 1 Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Yaoundé P. O. Box 2008 Messa, Cameroon 2 Department of Earth Science, University of Yaoundé 1, Yaoundé P. O. Box 812, Cameroon; [email protected] 3 Higher Institute of Rural Development (ISDR of Mbaïki), University of Bangui, Bangui P. O. Box 1450, Central African Republic (CAR); [email protected] 4 Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources Management, University of Kisangani, Kisangani P. O. Box 2012, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 December 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2020; Published: 7 April 2020 Abstract: Humid conditions and equatorial forest in the Congo Basin have allowed for the maintenance of significant biodiversity and carbon stock. The ecological services and products of this forest are of high importance, particularly for smallholders living in forest landscapes and watersheds. Unfortunately, in addition to deforestation and forest degradation, climate change/variability are impacting this region, including both forests and populations. We developed three case studies based on field observations in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as information from the literature. Our key findings are: (1) the forest-related water cycle of the Congo Basin is not stable, and is gradually changing; (2) climate change is impacting the water cycle of the basin; and, (3) the slow modification of the water cycle is affecting livelihoods in the Congo Basin.