The Forests of the Congo Basin – State of the Forest 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

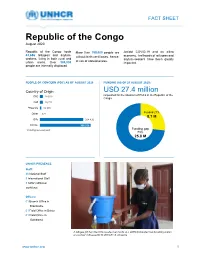

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Vascular Plant Survey of Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve, Malawi

YIKA-VWAZA TRUST RESEARCH STUDY REPORT N (2017/18) Vascular Plant Survey of Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve, Malawi By Sopani Sichinga ([email protected]) September , 2019 ABSTRACT In 2018 – 19, a survey on vascular plants was conducted in Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve. The reserve is located in the north-western Malawi, covering an area of about 986 km2. Based on this survey, a total of 461 species from 76 families were recorded (i.e. 454 Angiosperms and 7 Pteridophyta). Of the total species recorded, 19 are exotics (of which 4 are reported to be invasive) while 1 species is considered threatened. The most dominant families were Fabaceae (80 species representing 17. 4%), Poaceae (53 species representing 11.5%), Rubiaceae (27 species representing 5.9 %), and Euphorbiaceae (24 species representing 5.2%). The annotated checklist includes scientific names, habit, habitat types and IUCN Red List status and is presented in section 5. i ACKNOLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, let me thank the Nyika–Vwaza Trust (UK) for funding this work. Without their financial support, this work would have not been materialized. The Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) Malawi through its Regional Office (N) is also thanked for the logistical support and accommodation throughout the entire study. Special thanks are due to my supervisor - Mr. George Zwide Nxumayo for his invaluable guidance. Mr. Thom McShane should also be thanked in a special way for sharing me some information, and sending me some documents about Vwaza which have contributed a lot to the success of this work. I extend my sincere thanks to the Vwaza Research Unit team for their assistance, especially during the field work. -

CITY of OAKLAND PUBLIC ETHICS COMMISSION One Frank Ogawa Plaza (City Hall) Special Commission Meeting Teleconference Thursday, July 16, 2020 6:30 P.M

CITY OF OAKLAND PUBLIC ETHICS COMMISSION One Frank Ogawa Plaza (City Hall) Special Commission Meeting Teleconference Thursday, July 16, 2020 6:30 p.m. Commissioners: James E.T. Jackson (Chair), Nayeli Maxson Velázquez (Vice-Chair), Jill M. Butler, Michael MacDonald, Janani Ramachandran, Joseph Tuman and Jerett Yan Commission Staff to attend: Whitney Barazoto, Executive Director; Suzanne Doran, Lead Analyst – Civic Technology and Engagement; Kellie Johnson, Enforcement Chief; Simon Russell, Investigator City Attorney Staff: Trish Shafie, Deputy City Attorney PUBLIC ETHICS COMMISSION (PEC or COMMISSION) SPECIAL MEETING NOTE: Pursuant to the Governor's Executive Order N-29-20 and City of Oakland Emergency Order dated March 23, 2020, suspending the Sunshine Ordinance, all members of the Commission and participating PEC staff will join the meeting via phone/internet audio conference, and the following options for public viewing and participation are available: . Television: KTOP channel 10 on Xfinity (Comcast) or ATT Channel 99, locate City of Oakland KTOP – Channel 10 . Livestream online: Go to the City of Oakland’s KTOP livestream page here: https://www.oaklandca.gov/services/ktop-tv10-program-schedule click on “View” . Online video teleconference: Click on the link below to join the webinar: Please click this URL to join. https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87124781030?pwd=SmFuREVIbHhWRVBEaWVId2NFYjgwU T09 Password: 674732 o To comment by online video conference, click the “Raise Your Hand” button to request to speak when Public Comment is being taken on an eligible agenda item. You will then be unmuted, during your turn, and allowed to participate in public comment. After the allotted time, you will then be re- muted. -

Slang Terms and Code Words: a Reference for Law Enforcement

UNCLASSIFIED Slang Terms and Code Words: A Reference for Law DEA Enforcement Personnel Intelligence DEA-HOU-DIR-022-18 July 2018 ReportBrief 1 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED DEA Intelligence Report Executive Summary This Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Intelligence Report contains new and updated information on slang terms and code words from a variety of law enforcement and open sources, and serves as an updated version to the product entitled “Drug Slang Code Words” published by the DEA in May 2017. It is designed as a ready reference for law enforcement personnel who are confronted with hundreds of slang terms and code words used to identify a wide variety of controlled substances, designer drugs, synthetic compounds, measurements, locations, weapons, and other miscellaneous terms relevant to the drug trade. Although every effort was made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information presented, due to the dynamics of the ever-changing drug scene, subsequent additions, deletions, and corrections are inevitable. Future addendums and updates to this report will attempt to capture changed terminology to the furthest extent possible. This compendium of slang terms and code words is alphabetically ordered, with new additions presented in italic text, and identifies drugs and drug categories in English and foreign language derivations. Drug Slang Terms and Code Wordsa Acetaminophen and Oxycodone Combination (Percocet®) 512s; Bananas; Blue; Blue Dynamite; Blueberries; Buttons; Ercs; Greenies; Hillbilly Heroin; Kickers; M-30s; -

PENGARUH SKARIFIKASI PADA RESPON PERKECAMBAHAN BENIH KALIANDRA MERAH (Caliandra Calothyrsus Meissn.)

45 PENGARUH SKARIFIKASI PADA RESPON PERKECAMBAHAN BENIH KALIANDRA MERAH (Caliandra calothyrsus Meissn.) SKRIPSI CHRISTINA PUTRIANI SIAHAAN 161201088 DEPARTEMEN BUDIDAYA HUTAN FAKULTAS KEHUTANAN UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA 2020 Universitas Sumatera Utara 45 PENGARUH SKARIFIKASI PADA RESPON PERKECAMBAHAN BENIH KALIANDRA MERAH (Caliandra calothyrsus Meissn.) SKRIPSI Oleh: CHRISTINA PUTRIANI SIAHAAN 161201088 Skripsi sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana di Fakultas Kehutanan Universitas Sumatera Utara DEPARTEMEN BUDIDAYA HUTAN FAKULTAS KEHUTANAN UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA 2020 Universitas Sumatera Utara 45 PENGESAHAN SKRIPSI Judul Penelitian : Pengaruh Skarifikasi pada Respon Perkecambahan Benih Kaliandra Merah (Caliandra calothyrsus Meissn.) Nama : Christina Putriani Siahaan NIM : 161201088 Departemen : Budidaya Hutan Fakultas : Kehutanan Disetujui oleh, Komisi Pembimbing Dr. Kansih Sri Hartini, S.Hut., M.P. Ketua Tanggal Lulus: 14 Agustus 2020 i Universitas Sumatera Utara 45 PERNYATAAN ORIGINALITAS Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Christina Putriani Siahaan NIM : 161201088 Judul Skripsi : Pengaruh Skarifikasi pada Respon Perkecambahan Benih Kaliandra Merah (Caliandra calothyrsus Meissn.) menyatakan bahwa skripsi ini adalah hasil karya sendiri. Pengutipan-pengutipan yang penulis lakukan pada bagian-bagian tertentu dari hasil karya orang lain dalam penulisan skripsi ini, telah penulis cantumkan sumbernya secara jelas sesuai dengan norma, kaidah, dan etika penulisan ilmiah. Medan, Agustus 2020 Christina Putriani -

Reconstruction Under Fire: Case Studies and Further Analysis Of

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Reconstruction Under Fire Case Studies and Further Analysis of Civil Requirements A COMPANION VOLUME TO RECONSTRUCTION UNDER FIRE: UNIFYING CIVIL AND MILITARY COUNTERINSURGENCY Brooke Stearns Lawson, Terrence K. -

Complete Index of Common Names: Supplement to Tropical Timbers of the World (AH 607)

Complete Index of Common Names: Supplement to Tropical Timbers of the World (AH 607) by Nancy Ross Preface Since it was published in 1984, Tropical Timbers of the World has proven to be an extremely valuable reference to the properties and uses of tropical woods. It has been particularly valuable for the selection of species for specific products and as a reference for properties information that is important to effective pro- cessing and utilization of several hundred of the most commercially important tropical wood timbers. If a user of the book has only a common or trade name for a species and wishes to know its properties, the user must use the index of common names beginning on page 451. However, most tropical timbers have numerous common or trade names, depending upon the major region or local area of growth; furthermore, different species may be know by the same common name. Herein lies a minor weakness in Tropical Timbers of the World. The index generally contains only the one or two most frequently used common or trade names. If the common name known to the user is not one of those listed in the index, finding the species in the text is impossible other than by searching the book page by page. This process is too laborious to be practical because some species have 20 or more common names. This supplement provides a complete index of common or trade names. This index will prevent a user from erroneously concluding that the book does not contain a specific species because the common name known to the user does not happen to be in the existing index. -

Diversification of Tree Crops: Domestication of Companion Crops for Poverty Reduction and Environmental Services

Expl Agric. (2001), volume 37, pp. 279±296 Printed in Great Britain Copyright # 2001 Cambridge University Press REVIEW PAPER DIVERSIFICATION OF TREE CROPS: DOMESTICATION OF COMPANION CROPS FOR POVERTY REDUCTION AND ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES By R. R. B. LEAKEY{ and Z. TCHOUNDJEU{ {Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Bush Estate, Penicuik, Midlothian, EH26 0QB, Scotland, UK and {International Centre for Research in Agroforestry, PO Box 2067, YaoundeÂ, Cameroon (Accepted 19 January 2001) SUMMARY New initiatives in agroforestry are seeking to integrate indigenous trees, whose products have traditionally been gathered from natural forests, into tropical farming systems such as cacao farms. This is being done to provide from farms, marketable timber and non-timber forest products that will enhance rural livelihoods by generating cash for resource-poor rural and peri-urban households. There are many potential candidate species for domestication that have commercial potential in local, regional or even international markets. Little or no formal research has been carried out on many of these hitherto wild species to assess potential for genetic improvement, reproductive biology or suitability for cultivation. With the participation of subsistence farmers a number of projects to bring candidate species into cultivation are in progress, however. This paper describes some tree domestication activities being carried out in southern Cameroon, especially with Irvingia gabonensis (bush mango; dika nut) and Dacryodes edulis (African plum; safoutier). As part of this, fruits and kernels from 300 D. edulis and 150 I. gabonensis trees in six villages of Cameroon and Nigeria have been quantitatively characterized for 11 traits to determine combinations de®ning multi-trait ideotypes for a genetic selection programme. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Primate Aesthetics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2016 Primate Aesthetics Chelsea L. Sams University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sams, Chelsea L., "Primate Aesthetics" (2016). Masters Theses. 375. https://doi.org/10.7275/8547766 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/375 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2016 Department of Art PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________ Robin Mandel, Chair ___________________________________ Melinda Novak, Member ___________________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member ___________________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION For Christopher. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am truly indebted to my committee: Robin Mandel, for his patient guidance and for lending me his Tacita Dean book; to Melinda Novak for taking a chance on an artist, and fostering my embedded practice; and to Jenny Vogel for introducing me to the medium of performance lecture. To the longsuffering technicians Mikaël Petraccia, Dan Wessman, and Bob Woo for giving me excellent advice, and tolerating question after question. -

Cameroon 2014 Table A

Cameroon 2014 Table A: Total funding and outstanding pledges* as of 29 September 2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R10) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and appealing organizations. Donor Channel Description Funding Outstanding Pledges USD USD Allocation of unearmarked funds by FAO The assistance is intended to cover the immediate needs of 493,000 0 FAO refugees and host populations on agricultural inputs to enable households engaged in agricultural activities boost vegetable production during the off-season 2014 (August to November). This should improve food security and generate income through the sale of surpluses. In addition, in order to promote a more sustainable approach, the project will provide cereals and cassava processing facilities in host villages, coupled with training sessions. This will reduce post-harvest losses in corn and cassava, and thus help to strengthen the resilience of target populations. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation IMC to respond to the cholera outbreak in the Far North region in 900,000 0 Cameroon and to address the humanitarian needs of CAR refugees in the East and Adamawa regions of Cameroon Canada IFRC IFRC DREF operation MDRCM015 in Cameroon - IFRC 32,802 0 December 2013 operation to assist CAR refugees in Cameroon (M013807) Carry-over (donors not specified) WFP to be allocated to specific project 31,201 0 Central Emergency Response Fund WHO Medical assistance to local communities and refugees in 55,774 0 response to ongoing nutritional crisis, cholera and measles