0816639442.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

Margaret Matthews Wilburn

Tennessee State University Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University Tennessee State University Olympians Tennessee State University Olympic History 7-2020 Margaret Matthews Wilburn Julia Huskey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.tnstate.edu/tsu-olympians Part of the Sports Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Margaret Matthews (Wilburn) Margaret Matthews (Wilburn) was a sprinter and long-jumper for TSU. She competed in both the long jump and the 4 x 100 meter relay in the 1956 Olympics, where she won the bronze medal in the latter. In 1958, she became the first American woman to long-jump 20 feet. She was a member of several of TSU’s national champion relay teams. Matthews was born in 1935 in Griffin, Georgia. She attended David T. Howard High School, which produced several other world-class athletes (including high-jumper Mildred McDaniel Singleton); a gym teacher at Howard, Marion Armstrong-Perkins (Morgan), encouraged her to participate in sports.i After Matthews’s graduation from high school, she first attended Bethune Cookman College, and she then competed for the Chicago Catholic Youth Organization before she enrolled at TSU. Matthews was known for pushing her teammates in practice: Wilma Rudolph said, “Margaret would openly challenge anybody on the track. Every day. You'd think 'My God, I have to feel this every day?'”ii As a Tigerbelle, Matthews won the AAU outdoor long jump title four years in a row (from 1956 to 1959) and the 100 meter outdoor title once (in 1958)iii. Although she set an American record of 19 feet, 9.25 inches in the long jump at the 1956 Olympic Trialsiv, the Olympic Games did not go well for her: she fouled on her first two attempts and jumped far short of her best on the third jump, so she did not qualify for the finalsv. -

Recordtiming.Com

RecordTiming.com - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER Page 1 Payton Jordan Cardinal Invitational Stanford University --Stanford, California Results 7 502 Scott Buttinger Stanford 1:52.93 Event 1 Men 100 Meter Dash 52.162 (52.162) Name School Finals Section 1 Wind: -2.0 Event 7 Men 800 Meter Run Section 4 1 252 Juan Carlos Alanis Mexico-FMAA 10.84 Name School Finals 2 511 Miguel Shaw Stanford 11.53 Section 1 1 681 Nick Rivera Texas Tech 1:50.19 Event 4 Men 800 Meter Run Section 1 54.615 (54.615) Name School Finals 2 560 Tyler Smith U. of Victor 1:50.34 Section 1 53.238 (53.238) 1 81 Casimir Loxsom Brooks Beast 1:48.38 3 110 Jordan Locklear California 1:50.99 54.914 (54.914) 53.678 (53.678) 2 223 Edward Kemboi Iowa State 1:48.47 4 434 Nathanael Litwiller Sacramento S 1:51.18 55.079 (55.079) 53.983 (53.983) 3 83 Mark Weiczorek Brooks Beast 1:48.94 5 633 Christian DeLago Unattached-I 1:52.04 55.249 (55.249) 54.452 (54.452) 4 506 Luke Lefebure Stanford 1:50.16 6 654 Martin Dally Virginia Tec 1:52.20 54.728 (54.728) 52.649 (52.649) 5 193 Geoff Harris Halifast 1:52.29 7 607 Terrance Ellis Unattached 1:53.45 55.539 (55.539) 53.523 (53.523) --- 415 Za'Von Watkins Penn State DNF 54.954 (54.954) Event 8 Men 800 Meter Run Section 5 --- 475 Anthony Romaniw Speed River DNF Name School Finals 54.546 (54.546) Section 1 1 281 Matthew Tex Montana Stat 1:50.01 Event 5 Men 800 Meter Run Section 2 55.164 (55.164) Name School Finals 2 279 Grant Grosvenor Montana Stat 1:50.25 Section 1 56.137 (56.137) 1 270 Eliud Rutto Mid. -

NEWSLETTER Supplementingtrack & FIELD NEWS Twice Monthly

TRACKNEWSLETTER SupplementingTRACK & FIELD NEWS twice monthly. Vol. 10, No. 1 August 14, 1963 Page 1 Jordan Shuffles Team vs. Germany British See 16'10 1-4" by Pennel Hannover, Germany, July 31- ~Aug. 1- -Coach Payton Jordan London, August 3 & 5--John Pennel personally raised the shuffled his personnel around for the dual meet with West Germany, world pole vault record for the fifth time this season to 16'10¼" (he and came up with a team that carried the same two athletes that com has tied it once), as he and his U.S. teammates scored 120 points peted against the Russians in only six of the 21 events--high hurdles, to beat Great Britain by 29 points . The British athl_etes held the walk, high jump, broad jump, pole vault, and javelin throw. His U.S. Americans to 13 firsts and seven 1-2 sweeps. team proceeded to roll up 18 first places, nine 1-2 sweeps, and a The most significant U.S. defeat came in the 440 relay, as 141 to 82 triumph. the Jones boys and Peter Radford combined to run 40 . 0, which equal The closest inter-team race was in the steeplechase, where ed the world record for two turns. Again slowed by poor baton ex both Pat Traynor and Ludwig Mueller were docked in 8: 44. 4 changes, Bob Hayes gained up to five yards in the final leg but the although the U.S. athlete was given the victory. It was Traynor's U.S. still lost by a tenth. Although the American team had hoped second fastest time of the season, topped only by his mark against for a world record, the British victory was not totally unexpected. -

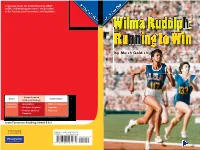

Leveled Reader - Wilma Rudolph Running to Win - BLUE.Pdf

52527_CVR.indd Page A-B 6/11/09 11:18:32 PM user-044 /Volumes/104/SF00327/work%0/indd%0/SF_RE_TX:NL_L... Suggested levels for Guided Reading, DRA,™ Lexile,® and Reading Recovery™ are provided in the Pearson Scott Foresman Leveling Guide. byby MeishMeish GoldishGoldish Comprehension Genre Text Features Skills and Strategy Expository • Generalize • Table of Contents nonfi ction • Author’s Purpose • Captions • Predict and Set • Glossary Purpose Scott Foresman Reading Street 5.4.2 ISBN-13: 978-0-328-52527-0 ISBN-10: 0-328-52527-8 90000 9 780328 525270 LeYWXkbWho :WbcWj_Wd \h_bbo fhec[dWZ_d] ifhW_d[Z XoC[_i^=ebZ_i^Xo C[_i^ =ebZ_i^ ikXij_jkj[ MehZYekdj0(")+, Note: The total word count includes words in the running text and headings only. Numerals and words in chapter titles, captions, labels, diagrams, charts, graphs, sidebars, and extra features are not included. (MFOWJFX *MMJOPJTt#PTUPO .BTTBDIVTFUUTt$IBOEMFS "SJ[POBt 6QQFS4BEEMF3JWFS /FX+FSTFZ Chapter 1 A Difficult Childhood . 4 Chapter 2 The Will to Walk . 8 Chapter 3 Photographs New Opportunities. 12 Every effort has been made to secure permission and provide appropriate credit for photographic material. The publisher deeply regrets any omission and pledges to correct errors called to its attention in subsequent editions. Chapter 4 Unless otherwise acknowledged, all photographs are the property of Pearson The 1960 Olympics . 16 Education, Inc. Photo locators denoted as follows: Top (T), Center (C), Bottom (B), Left (L), Right (R), Background (Bkgd) Chapter 5 Helping Others . 20 Opener Jerry Cooke/Corbis; 1 ©AP Images; 5 Hulton Archive/Getty Images; 6 Stan Wayman/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 7 Margaret Bourke-White/Time Life Pictures/ Getty Images; 8 ©AP Images; 9 Francis Miller/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 10 ©iStockphoto; 11 Mark Humphrey/©AP Images; 12 John J. -

Turns&Distances

TTuurrnnss && DDiissttaanncceess A publication of the Officials Committee of the Pacific Association USA Track & Field Jim Hume, 1561 Marina Court, Unit B, San Mateo, CA 94403-5593… (650) 571-5913 Wednesday, July 16, 2014 AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS Encounters with the Elders: Dr. Leon Glover USATF OFFICIALS HALL OF FAME Speaks By Bruce Colman 2007 ....................... Horace Crow Leo Costanzo At a track meet, you will almost always find Leon Glover, Jr., 2008 ....................... Lori Maynard next to the horizontal jumps runway, 20 meters back from the George Kleeman take-off board, with a clipboard on his lap, tending to a scientific 2009 ....................... Dick Connors 2010 ....................... Bob Podkaminer instrument mounted on a tripod, recording every wind reading for every long-jump or triple-jump trial. THE DICK BARBOUR MERITORIOUS SERVICE AWARD Aside from being Pacific Association’s doctor of the wind 1985 ................... Hank Patton gauge, Leon is a rarity in the officiating world: the scion of an 1986 ................... George Newlon earlier generation of officials, and he was present at the creation Roxanne Anderson of the whole wind-reading discipline. His father was recording 1987 ................... Dan Dotta Del Dotta wind readings as far back as the late 1940’s and helped develop 1988 ................... Harry Young some of the earliest instruments we use today. Henry “Hank” Weston He agreed to talk with 1989 ................... Ed Parker Turns and Distances recently Harmon Brown 1990 ................... Horace Crow about his careers on and off 1991 (No award) the field of play, his outside 1992 Dick Connors interests…and family 1993 ................... George Kleeman heritage. This got into some 1994 ................... Tom Moore pretty deep sport history. -

The History of the Pan American Games

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 The iH story of the Pan American Games. Curtis Ray Emery Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Emery, Curtis Ray, "The iH story of the Pan American Games." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/977 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—3376 microfilmed exactly as received EMERY, Curtis Ray, 1917- THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES. Louisiana State University, Ed.D., 1964 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education m The Department of Health, Physical, and Recreation Education by Curtis Ray Emery B. S. , Kansas State Teachers College, 1947 M. S ., Louisiana State University, 1948 M. Ed. , University of Arkansas, 1962 August, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Illustrations are not original copy. These pages tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the close co operation and assistance of many individuals who gave freely of their time. -

Welcome to the Issue

Welcome to the issue Volker Kluge Editor It is four years since we decided to produce the Journal triple jump became the “Brazilian” discipline. History of Olympic History in colour. Today it is scarcely possible and actuality at the same time: Toby Rider has written to imagine it otherwise. The pleasing development of about the first, though unsuccessful, attempt to create ISOH is reflected in the Journal which is now sent to 206 an Olympic team of refugees, and Erik Eggers, who countries. accompanied Brazil’s women’s handball team, dares to That is especially thanks to our authors and the small look ahead. team which takes pains to ensure that this publication Two years ago Myles Garcia researched the fate of can appear. As editor I would like to give heartfelt the Winter Olympic cauldrons. In this edition he turns thanks to all involved. his attention to the Summer Games. Others have also It is obvious that the new edition is heavily influenced contributed to this piece. by the Olympic Games in Rio. Anyone who previously Again there are some anniversaries. Eighty years ago believed that Brazilian sports history can be reduced the Games of the XI Olympiad took place in Berlin, to to football will have to think again. The Olympic line of which the Dutch water polo player Hans Maier looks ancestry begins as early as 1905, when the IOC presented back with mixed feelings. The centenarian is one of the the flight pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont with one of few surviving participants. the first four Olympic Diplomas. -

Otro Año Sin Neoliberalismo FIL-2020: Hermandad Cuba-Vietnam

ISSN - 0864-0033 AÑO LIX 2020 No. 458 # 458 Otro año sin FIL-2020: Hermandad Habanos en Festival neoliberalismo Cuba-Vietnam Havana Cigars Another Year without FIL-2020: Brotherhood in Festival Neoliberalism Cuba-Vietnam Pág. 4 Pág. 10 Pág. 14 Agencia multimediática con más de 40 corresponsalías y un centenar de colaboradores en todo el mundo. Unos 6 000 usuarios en 61 países reciben nuestros servicios y suman millares las visitas diarias a los sitios web. OFRECEMOS SERVICIOS: • Informativos • Titulares en teléfonos móviles (enviar sms al 8100 con la palabra pl) • Televisivos • Editoriales • Fotográficos • Radiales • Productos Multimedia • Editorial Prensa Latina • Servicios de impresión Contáctenos a través de: Fundada en 1959 [email protected] Telf: 7 8383496/ 7 8301344 SUMARIO Cuba. Territorio libre de Cuba previene 4 neoliberalismo / Cuba. A 17 coronavirus / Cuba neoliberalism-free territory Prevents Coronavirus PRESIDENTE / PRESIDENT LUIS ENRIQUE GONZÁLEZ Feria Internacional del Espiral creciente para VICEPRESIDENTA EDITORIAL / 9 Libro-2020. / 20 el turismo en La Habana EDITORIAL VICEPRESIDENT LIANET ARIAS SOSA Book fair shows-2020 / Growingspiral for DIRECTORA EDITORIAL / tourism in Havana EDITORIAL DIRECTOR MARIELA PÉREZ VALENZUELA EDITOR / EDITOR JORGE PETINAUD MARTÍNEZ DIRECCIÓN DE ARTE / ART DIRECTION ANATHAIS RODRÍGUEZ SOTO DISEÑO Y REALIZACIÓN / DESIGN AND REALIZATION DAYMÍ AGUILAR Y FERNANDO TITO CORRECCIÓN / PROOFREADING FRANCISCO A. MUÑOZ GONZÁLEZ TRADUCTOR / TRANSLATOR JUAN GARCÍA LLERA Operación verdad, REDACCIÓN / ADDRESS Festival del Habano. 26 blindaje contra falsas Calle 21 No. 406, Vedado, La Habana 4, Cuba. Tel.: 7 832 1495 y 7 832 3578. 14 Los mejores humos noticias / Operation truth, [email protected] / The best Smokes www.cubarevista.prensa-latina.cu a shield against fake news VENTAS Y PUBLICIDAD / SALES AND ADVERTISING ERNESTO LÓPEZ ALONSO Misión médica de Cuba [email protected] 29 consolida presencia en 21 No. -

78-5890 MECHIKOFF, Robert Alan, 1949- the POLITICALIZATION of the XXI OLYMPIAD

78-5890 MECHIKOFF, Robert Alan, 1949- THE POLITICALIZATION OF THE XXI OLYMPIAD. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1977 Education, physical University Microfilms International,Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 © Copyright by Robert Alan Mechikoff 1977 THE POLITICALIZATION OF THE XXI OLYMPIAD DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Alan Mechikoff, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1977 Reading Committee Approved By Seymour Kleinman, Ph.D. Barbara Nelson, Ph.D. Lewis Hess, Ph.D. / Adviser / Schoc/l of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation This study is dedicated to Angela and Kelly Mechikoff; Alex and Aileen Mechikoff; Frank, Theresa, and Anthony Riforgiate; and Bob and Rosemary Steinbauer. Without their help, understanding and encouragement, the completion of this dissertation would not be possible. VITA November 7, 1949........... Born— Whittier, California 1971......................... B.A. , California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach California 1972-1974....................Teacher, Whittier Union High School District, Whittier, California 1975......................... M.A. , California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, California 1975-197 6 ....................Research Assistant, School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1976-197 7....................Instructor, Department of Physical Education, University of Minnesota, Duluth, Duluth, Minnesota FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Physical Education Studies in Philosophy of Sport and Physical Education. Professor Seymour Kleinman Studies in History of Sport and Physical Education. Professor Bruce L. Bennett Studies in Administration of Physical Education. Professor Lewis A. Hess TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................... iii VITA........................................................ iv Chapter I. -

1974 Age Records

TRACK AGE RECORDS NEWS 1974 TRACK & FIELD NEWS, the popular bible of the sport for 21 years, brings you news and features 18 times a year, including twice a month during the February-July peak season. m THE EXCITING NEWS of the track scene comes to you as it happens, with in-depth coverage by the world's most knowledgeable staff of track reporters and correspondents. A WEALTH OF HUMAN INTEREST FEATURES involving your favor ite track figures will be found in each issue. This gives you a close look at those who are making the news: how they do it and why, their reactions, comments, and feelings. DOZENS OF ACTION PHOTOS are contained in each copy, recap turing the thrills of competition and taking you closer still to the happenings on the track. STATISTICAL STUDIES, U.S. AND WORLD LISTS AND RANKINGS, articles on technique and training, quotable quotes, special col umns, and much more lively reading complement the news and the personality and opinion pieces to give the fan more informa tion and material of interest than he'll find anywhere else. THE COMPREHENSIVE COVERAGE of men's track extends from the Compiled by: preps to the Olympics, indoor and outdoor events, cross country, U.S. and foreign, and other special areas. You'll get all the major news of your favorite sport. Jack Shepard SUBSCRIPTION: $9.00 per year, USA; $10.00 foreign. We also offer track books, films, tours, jewelry, and other merchandise & equipment. Write for our Wally Donovan free T&F Market Place catalog. TRACK & FIELD NEWS * Box 296 * Los Altos, Calif. -

Protest at the Pyramid: the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Protest at the Pyramid: The 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B. Witherspoon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PROTEST AT THE PYRAMID: THE 1968 MEXICO CITY OLYMPICS AND THE POLITICIZATION OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES By Kevin B. Witherspoon A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kevin B. Witherspoon defended on Oct. 6, 2003. _________________________ James P. Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member _________________________ Valerie J. Conner Committee Member _________________________ Robinson Herrera Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been completed without the help of many individuals. Thanks, first, to Jim Jones, who oversaw this project, and whose interest and enthusiasm kept me to task. Also to the other members of the dissertation committee, V.J. Conner, Robinson Herrera, Patrick O’Sullivan, and Joe Richardson, for their time and patience, constructive criticism and suggestions for revision. Thanks as well to Bill Baker, a mentor and friend at the University of Maine, whose example as a sports historian I can only hope to imitate. Thanks to those who offered interviews, without which this project would have been a miserable failure: Juan Martinez, Manuel Billa, Pedro Aguilar Cabrera, Carlos Hernandez Schafler, Florenzio and Magda Acosta, Anatoly Isaenko, Ray Hegstrom, and Dr.