Introduction 1 the Origins of the Mafia As a Criminal Phenomenon and As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

Mafia E Mancato Sviluppo, Studi Psicologico- Clinici”

C.S.R. C.O.I.R.A.G. Centro Studi e Ricerche “Ermete Ronchi” LA MAFIA, LA MENTE, LA RELAZIONE Atti del Convegno “Mafia e mancato sviluppo, studi psicologico- clinici” Palermo, 20-23 maggio 2010 a cura di Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso QUADERNO REPORT N. 15 Copyright CSR 2011 1 INDICE Nota Editoriale, di Bianca Gallo Presentazione, di Claudio Merlo Introduzione, di Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso Cap. 1 - Ricerche psicologico-cliniche sul fenomeno mafioso • Presentazione, di Santo Di Nuovo Contributi di • Cecilia Giordano • Serena Giunta • Marie Di Blasi, Paola Cavani e Laura Pavia • Francesca Giannone, Anna Maria Ferraro e Francesca Pruiti Ciarello ◦ APPENDICE • Box Approfondimento ◦ Giovanni Pampillonia ◦ Ivan Formica Cap. 2 - Beni relazionali e sviluppo • Presentazione, di Aurelia Galletti Contributi di • Luisa Brunori e Chiara Bleve • Antonino Giorgi • Antonio Caleca • Antonio La Spina • Box Approfondimento ◦ Raffaele Barone, Sheila Sherba e Simone Bruschetta ◦ Salvatore Cernigliano 2 Cap. 3 - Un confronto tra le cinque mafie • Presentazione, di Gianluca Lo Coco Contributi di • Emanuela Coppola • Emanuela Coppola, Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso • Rosa Pinto e Ignazio Grattagliano • Box Approfondimento ◦ Paolo Praticò Cap. 4 - Psicoterapia e mafia • Presentazione, di Giuseppina Ustica Contributi di • Graziella Zizzo • Girolamo Lo Verso • Lorenzo Messina • Maurizio Gasseau Cap. 5 - Oltre il pensiero mafioso • Presentazione, di Antonio Caleca Contributi di • Leoluca Orlando • Maurizio De Lucia • Alfredo Galasso Conclusioni, di Girolamo Lo Verso e Serena Giunta Bibliografia Note 3 Nota editoriale di Bianca Gallo Questo Quaderno CSR, il n° 15, riporta le riflessioni sviluppate attraverso i diversi interventi durante il Convegno Mafia e mancato sviluppo, studi psicologico- clinici, che si è tenuto a Palermo il 20-23 maggio 2010. -

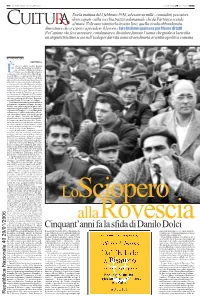

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

How the Mob and the Movie Studios Sold out the Hollywood Labor Movement and Set the Stage for the Blacklist

TRUE-LIFE NOIR How the Mob and the movie studios sold out the Hollywood labor movement and set the THE CHICAGO WAY stage for the Blacklist Alan K. Rode n the early 1930s, Hollywood created an indelible image crooked law enforcement, infected numerous American shook down businesses to maintain labor peace. Resistance The hard-drinking Browne was vice president of the Local of the urban gangster. It is a pungent irony that, less than metropolises—but Chicago was singularly venal. Everything by union officials was futile and sometimes fatal. At least 13 2 Stagehands Union, operated under the umbrella of IATSE a decade later, the film industry would struggle to escape and everybody in the Windy City was seemingly for sale. Al prominent Chicago labor leaders were killed; and not a single (The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, the vise-like grip of actual gangsters who threatened to Capone’s 1931 federal tax case conviction may have ended his conviction for any criminals involved.Willie Bioff and George Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts, here- bring the movie studios under its sinister control. reign as “Mr. Big,” but his Outfit continued to grow, exerting Browne were ambitious wannabes who vied for a place at after referred to as the IA). He had run unsuccessfully for the Criminal fiefdoms, created by an unholy trinity its dominion over various trade unions. Mobsters siphoned the union trough. Russian-born Bioff was a thug who served IA presidency in 1932. Bioff and Browne recognized in each Iof Prohibition-era gangsters, ward-heeling politicians, and off workers’ dues, set up their cohorts with no-show jobs, and the mob as a union slugger, pimp, and whorehouse operator. -

Servizio Della Biblioteca

ASSEMBLEA REGIONALE SICILIANA SERVIZIO DELLA BIBLIOTECA GIORNALI CORRENTI E CESSATI POSSEDUTI DALLA BIBLIOTECA Elenco in ordine alfabetico di titolo* Aggiornato a luglio 2020 TITOLO CONSISTENZA L’AGRICOLTURA MECCANIZZATA. Mensile 1955-1965 d'informazioni, tecnico, commerciale, sindacale, amministrativo, fiscale, a cura della Cooperativa trebbiatori. L’AMICO DEL POPOLO. Settimanale cattolico. 1957-1959 L’AMICO DEL POPOLO Si pubblica tutti i giorni di 1875-1881 mattina. L'APE IBLEA. Giornale per tutti [poi La Sicilia 1/1/1869-31/12/1870 cattolica]. L’ARTIGIANATO D’ITALIA. Organo della 10/1/1953-30/11/1986 Confederazione generale dell'artigianato d'Italia. L’ARTIGIANATO TRAPANESE. Organo mensile 1/1/1954-31/12/1955; 6/3/1957- dell'Associazione provinciale degli artigiani. 30/10/1958 ASSO DI BASTONI. Settimanale satirico 11/7/1948-17/10/1954 anticanagliesco. ATENEO PALERMITANO. Periodico dell'Università 1952-1956 degli studi di Palermo. AVANTI! 1949-1993 AVVENIRE [già Avvenire d’Italia]. 4/12/1968- L’AVVENIRE D’ITALIA [poi Avvenire]. 23/6/1911; 28/12/1911; 2/1/1965-1968 AVVISATORE. Settimanale commerciale - agricolo - 5/1/1946-31/12/1986 industriale - marittimo. L’AZIONE. 16/1/1915; 24/12/1915 AZIONE SINDACALE. Organo della Confederazione 8/1951-10/1952 italiana sindacati nazionali lavoratori. BANDIERA AZZURRA. Periodico monarchico di 16/7/1948-8/10/1949 opposizione BANDIERA ROSSA. Organo dei gruppi comunisti 15/01/1965-15/12/1966 rivoluzionari. BOLLETTINO DEI LAVORI E DEGLI APPALTI 1956-1974 DELLA CASSA PER IL MEZZOGIORNO. BULLETIN DE L'ÉXECUTIF ÉLARGI DE 12/7/1924 * Titoli ordinati parola per parola; in caso di titoli uguali si ordina secondo il sottotitolo; l’articolo iniziale non viene preso in considerazione. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

Palermo Open City: from the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders?

EUROPE AT A CROSSROADS : MANAGED INHOSPITALITY Palermo Open City: From the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders? LEOLUCA ORLANDO + SIMON PARKER LEOLUCA ORLANDO is the Mayor of Palermo and interview + essay the President of the Association of the Municipali- ties of Sicily. He was elected mayor for the fourth time in 2012 with 73% of the vote. His extensive and remarkable political career dates back to the late 1970s, and includes membership and a break PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 1 from the Christian Democratic Party; the establish- ment of the Movement for Democracy La Rete (“The Network”); and election to the Sicilian Regional Parliament, the Italian National Parliament, as well as the European Parliament. Struggling against organized crime, reintroducing moral issues into Italian politics, and the creation of a democratic society have been at the center of Oralando’s many initiatives. He is currently campaigning for approaching migration as a matter of human rights within the European Union. Leoluca Orlando is also a Professor of Regional Public Law at the University of Palermo. He has received many awards and rec- ognitions, and authored numerous books that are published in many languages and include: Fede e Politica (Genova: Marietti, 1992), Fighting the Mafia and Renewing Sicilian Culture (San Fran- Interview with Leolucca Orlando, Mayor of Palermo, Month XX, 2015 cisco: Encounter Books, 2001), Hacia una cultura de la legalidad–La experiencia siciliana (Mexico City: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, 2005), PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 2 and Ich sollte der nächste sein (Freiburg: Herder Leoluca Orlando is one of the longest lasting and most successful political lead- Verlag, 2010). -

Società E Cultura 65

Società e Cultura Collana promossa dalla Fondazione di studi storici “Filippo Turati” diretta da Maurizio Degl’Innocenti 65 1 Manica.indd 1 19-11-2010 12:16:48 2 Manica.indd 2 19-11-2010 12:16:48 Giustina Manica 3 Manica.indd 3 19-11-2010 12:16:53 Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al contributo di fondi di ricerca del Dipartimento di studi sullo stato dell’Università de- gli Studi di Firenze. © Piero Lacaita Editore - Manduria-Bari-Roma - 2010 Sede legale: Manduria - Vico degli Albanesi, 4 - Tel.-Fax 099/9711124 www.lacaita.com - [email protected] 4 Manica.indd 4 19-11-2010 12:16:54 La mafia non è affatto invincibile; è un fatto uma- no e come tutti i fatti umani ha un inizio e avrà anche una fine. Piuttosto, bisogna rendersi conto che è un fe- nomeno terribilmente serio e molto grave; e che si può vincere non pretendendo l’eroismo da inermi cittadini, ma impegnando in questa battaglia tutte le forze mi- gliori delle istituzioni. Giovanni Falcone La lotta alla mafia deve essere innanzitutto un mo- vimento culturale che abitui tutti a sentire la bellezza del fresco profumo della libertà che si oppone al puzzo del compromesso, dell’indifferenza, della contiguità e quindi della complicità… Paolo Borsellino 5 Manica.indd 5 19-11-2010 12:16:54 6 Manica.indd 6 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Alla mia famiglia 7 Manica.indd 7 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Leggenda Archivio centrale dello stato: Acs Archivio di stato di Palermo: Asp Public record office, Foreign office: Pro, Fo Gabinetto prefettura: Gab. -

Rapporto 2019 Sull'industria Dei Quotidiani in Italia

RAPPORTO 2019 RAPPORTO RAPPORTO 2019 sull’industria dei quotidiani in Italia Il 17 dicembre 2012 si è ASSOGRAFICI, costituito tra AIE, ANES, ASSOCARTA, SLC-‐CGIL, FISTEL-‐CISL e UILCOM, UGL sull’industria dei quotidiani in Italia CHIMICI, il FONDO DI ASSISTENZA SANITARIA INTEGRATIVA “Salute Sempre” per il personale dipendente cui si applicano i seguenti : CCNL -‐CCNL GRAFICI-‐EDITORIALI ED AFFINI -‐ CCNL CARTA -‐CARTOTECNICA -‐ CCNL RADIO TELEVISONI PRIVATE -‐ CCNL VIDEOFONOGRAFICI -‐ CCNL AGIS (ESERCENTI CINEMA; TEATRI PROSA) -‐ CCNL ANICA (PRODUZIONI CINEMATOGRAFICHE, AUDIOVISIVI) -‐ CCNL POLIGRAFICI Ad oggi gli iscritti al Fondo sono circa 103 mila. Il Fondo “Salute Sempre” è senza fini di lucro e garantisce agli iscritti ed ai beneficiari trattamenti di assistenza sanitaria integrativa al Servizio Sanitario Nazionale, nei limiti e nelle forme stabiliti dal Regolamento Attuativo e dalle deliberazioni del Consiglio Direttivo, mediante la stipula di apposita convenzione con la compagnia di assicurazione UNISALUTE, autorizzata all’esercizio dell’attività di assicurazione nel ramo malattia. Ogni iscritto potrà usufruire di prestazioni quali visite, accertamenti, ricovero, alta diagnostica, fisioterapia, odontoiatria . e molto altro ancora Per prenotazioni: -‐ www.unisalute.it nell’area riservata ai clienti -‐ telefonando al numero verde di Unisalute -‐ 800 009 605 (lunedi venerdi 8.30-‐19.30) Per info: Tel: 06-‐37350433; www.salutesempre.it Osservatorio Quotidiani “ Carlo Lombardi ” Il Rapporto 2019 sull’industria dei quotidiani è stato realizzato dall’Osservatorio tecnico “Carlo Lombardi” per i quotidiani e le agenzie di informazione. Elga Mauro ha coordinato il progetto ed ha curato la stesura dei testi, delle tabelle e dei grafici di corredo e l’aggiornamento della Banca Dati dell’Industria editoriale italiana La versione integrale del Rapporto 2019 è disponibile sul sito www.ediland.it Osservatorio Tecnico “Carlo Lombardi” per i quotidiani e le agenzie di informazione Via Sardegna 139 - 00187 Roma - tel. -

Archivio Nisseno N. 3

Associazione “Officina del libro Luciano Scarabelli” - Caltanissetta ARCHIVIO NISSENO Rassegna di storia, lettere, arte e società Anno II - N. 3 Luglio-Dicembre 2008 Paruzzo Printer editore - Caltanissetta 1 ARCHIVIO NISSENO Rassegna semestrale di storia, lettere, arte e società dell’Associazione “Officina del libro Luciano Scarabelli” di Caltanissetta Anno II - N. 3 Luglio-Dicembre 2008 2 Torniamo a parlare dei Fasci dei Lavoratori. La drammatica vicenda dei Fasci dei Lavoratori in Sicilia rappresenta la fase conclusiva di un lungo processo di crisi che si manifestò nel distorto svi- luppo dell’economia siciliana dell’Ottocento e nelle forme che assunse la politica a livello delle amministrazioni locali ma anche a livello nazionale. Se si guarda bene alle cause di questa crisi, molte di esse vanno individua- te nel mancato “governo” dei processi che determinarono una aberrante ridi- stribuzione della grande proprietà fondiaria. L’idea che fu alla base dell’ever- sione delle terre feudali (1812) e delle ricorrenti confische delle terre eccle- siastiche, cioè che si potesse creare una piccola proprietà contadina attraver- so la quotizzazione delle proprietà divenute demaniali, fallì miseramente a causa dell’ingordigia dei proprietari terrieri che aggirarono in tanti modi la legge, grazie anche alla connivenza del potere politico. Si andò così determinando, specialmente dal 1860 in poi, una situazione paradossale: la ridistribuzione delle terre, che era una delle grandi aspirazio- ni dei contadini siciliani alimentata anche dalle promesse di Garibaldi, non solo non si realizzò nei modi sperati, ma divenne un grande inganno che determinò un progressivo impoverimento del mondo contadino e braccianti- le, fino a giungere alle condizioni di estremo degrado e di miseria dei primi anni ‘90. -

Processo Lima

CORTE DI ASSISE - SEZIONE SECONDA IN NOME DEL POPOLO ITALIANO L’anno millenovecentonovantotto il giorno quindici del mese di luglio, riunita in Camera di Consiglio e così composta: 1. Dott. Giuseppe Nobile Presidente 2. Dott. Mirella Agliastro Giudice a latere 3. Sig. Spinella Giuseppe Giudice Popolare 4. “ Cangialosi Maria “ “ 5. “ Arceri Mimma “ “ 6. “ Vitale Rosa “ “ 7. “ Urso Rosa “ “ 8. “ Rizzo Giuseppe “ “ Con l’intervento del Pubblico Ministero rappresentato dal Sostituto Procuratore della Repubblica Dott. Gioacchino Natoli, e con l’assisstenza dell’ausiliario Lidia D’Amore ha emesso la seguente SENTENZA nei procedimenti riuniti e iscritti ai N 9/94 R.G.C.A, 21/96 R.G.C.A. 12/96 R.G.C. A. CONTRO 1 1) RIINA Salvatore n. Corleone il 16.11.1930 Arrestato il 18.01.1993 - Scarcerato il 05.05.1997 LIBERO- Detenuto per altro - Assente per rinunzia Assistito e difeso Avv. Cristoforo Fileccia Avv. Mario Grillo 2) MADONIA Francesco n. Palermo il 31.03.1924 Arrestato il 21.04.1995 - Scarcerato il 05.05.1997 LIBERO - Detenuto per altro - Assente per Rinunzia Assistito e difeso Avv. Giovanni Anania Avv. Nicolò Amato del foro di Roma 3) BRUSCA Bernardo n. San Giuseppe Jato il 09.09.1929 Arrestato il 21.10.1992 - Scarcerato il 05.05.1997 LIBERO - Detenuto per altro - Assente per Rinunzia Assistito e difeso Avv. Ernesto D’Angelo 4) BRUSCA Giovanni n. San Giuseppe Jato il 20.02.1957 Arrestato il 23.05.1996 - Scarcerato il 10.04.1998 LIBERO - Detenuto per altro - Assente per Rinunzia Assistito e difeso Avv. Luigi Li Gotti del foro di Roma Avv. -

History of Italian Mafia Spring 2019

Lecture Course SANTA REPARATA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OF ART Course Syllabus Semester : Spring 2019 Course Title: History of Italian Mafia Course Number: HIST 297 Meeting times: Tuesdays and Thursdays 12:40pm-4:00pm Location: Room 207, Main Campus, Piazza Indipendenza Instructor: Professor Lorenzo Pubblici Ph.D. E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays, 9am-11am, but don’t hesitate writing for any problem or doubt to my email address. 1. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course will examine the history of the Italian Mafia, starting with the Unification of Italy up to the present. The approach will be both political-historical and sociological. A discussion of the major protagonists, in the flight against the Cosa Nostra such as Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borselino will be an integral part of this course. The course will end with a discussion of contemporary organized crime in Italy. This semester in particular, we will focus on the so-called new mafia, the ‘ndrangheta, a powerful and growing organization rooted in Calabria but present all over Europe. 2. CONTENT INTRODUCTION: The course begins with an analysis of the roots of the Italian mafia that lay within the over reliance on codes of honor and on traditional family values as a resolution to all conflicts. Historically we begin in the Middle Ages with the control of agricultural estates by the mafia, the exploitation of peasants, and the consequent migration of Sicilians towards the United States at the end of the 19th century. We then focus on the controversial relationship between the mafia and the fascist state, and the decline of organized crime under fascism.