Memory and the Timeless Time of Eros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Pathogens, Personality, and Culture: Disease Prevalence Predicts Worldwide Variability in Sociosexuality, Extraversion, and Openness to Experience

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 2008 by the American Psychological Association 2008, Vol. 95, No. 1, 212–221 0022-3514/08/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.212 Pathogens, Personality, and Culture: Disease Prevalence Predicts Worldwide Variability in Sociosexuality, Extraversion, and Openness to Experience Mark Schaller and Damian R. Murray University of British Columbia Previous research has documented cross-cultural differences in personality traits, but the origins of those differences remain unknown. The authors investigate the possibility that these cultural differences can be traced, in part, to regional differences in the prevalence in infectious diseases. Three specific hypotheses are deduced, predicting negative relationships between disease prevalence and (a) unrestricted sociosex- uality, (b) extraversion, and (c) openness to experience. These hypotheses were tested empirically with methods that employed epidemiological atlases in conjunction with personality data collected from individuals in dozens of countries worldwide. Results were consistent with all three hypotheses: In regions that have historically suffered from high levels of infectious diseases, people report lower mean levels of sociosexuality, extraversion, and openness. Alternative explanations are addressed, and possible underlying mechanisms are discussed. Keywords: culture, disease prevalence, extraversion, openness to experience, sociosexuality People’s personalities differ, and some of that individual vari- For example, Schmitt (2005) and his collaborators in the Inter- ability is geographically clumped. But why is that so? How are we national Sexuality Description Project assessed worldwide vari- to understand the origins of regional differences in personality? A ability in chronic tendencies toward either a “restricted” or “unre- complete response to that question will surely require attention to stricted” sociosexual style. -

Feeling and Decision Making: the Appraisal-Tendency Framework

Feelings and Consumer Decision Making: Extending the Appraisal-Tendency Framework The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lerner, Jennifer S., Seunghee Han, and Dacher Keltner. 2007. “Feelings and Consumer Decision Making: Extending the Appraisal- Tendency Framework.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 17 (3) (July): 181–187. doi:10.1016/s1057-7408(07)70027-x. Published Version 10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70027-X Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37143006 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Feelings and Consumer Decision Making 1 Running head: FEELINGS AND CONSUMER DECISION MAKING Feelings and Consumer Decision Making: The Appraisal-Tendency Framework Seunghee Han, Jennifer S. Lerner Carnegie Mellon University Dacher Keltner University of California, Berkeley Invited article for the Journal of Consumer Psychology Draft Date: January 3rd, 2006 Correspondence Address: Seunghee Han Department of Social and Decision Sciences Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Phone: 412-268-2869, Fax: 412-268-6938 Email: [email protected] Feelings and Consumer Decision Making 2 Abstract This article presents the Appraisal Tendency Framework (ATF) (Lerner & Keltner, 2000, 2001; Lerner & Tiedens, 2006) as a basis for predicting the influence of specific emotions on consumer decision making. In particular, the ATF addresses how and why specific emotions carry over from past situations to color future judgments and choices. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Disgust: Evolved Function and Structure

Psychological Review © 2012 American Psychological Association 2013, Vol. 120, No. 1, 65–84 0033-295X/13/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0030778 Disgust: Evolved Function and Structure Joshua M. Tybur Debra Lieberman VU University Amsterdam University of Miami Robert Kurzban Peter DeScioli University of Pennsylvania Brandeis University Interest in and research on disgust has surged over the past few decades. The field, however, still lacks a coherent theoretical framework for understanding the evolved function or functions of disgust. Here we present such a framework, emphasizing 2 levels of analysis: that of evolved function and that of information processing. Although there is widespread agreement that disgust evolved to motivate the avoidance of contact with disease-causing organisms, there is no consensus about the functions disgust serves when evoked by acts unrelated to pathogen avoidance. Here we suggest that in addition to motivating pathogen avoidance, disgust evolved to regulate decisions in the domains of mate choice and morality. For each proposed evolved function, we posit distinct information processing systems that integrate function-relevant information and account for the trade-offs required of each disgust system. By refocusing the discussion of disgust on computational mechanisms, we recast prior theorizing on disgust into a framework that can generate new lines of empirical and theoretical inquiry. Keywords: disgust, adaptation, evolutionary psychology, emotion, cognition Research concerning disgust has expanded in recent years (Ola- selection pressure driving the evolution of the disgust system, but tunji & Sawchuk, 2005; Rozin, Haidt, & McCauley, 2009), and there has been less precision in identifying the selection pressures contemporary disgust researchers generally agree that an evolu- driving the evolution of disgust systems unrelated to pathogen tionary perspective is necessary for a comprehensive understand- avoidance (e.g., behavior in the sexual and moral domains). -

All in the Family: Attitudes Towards Cousin Marriages Among Young Dutch People from Various Ethnic Groups

Original Evolution, Mind and Behaviour 15(2017), 1–15 article DOI: 10.1556/2050.2017.0001 ALL IN THE FAMILY: ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGES AMONG YOUNG DUTCH PEOPLE FROM VARIOUS ETHNIC GROUPS ABRAHAM P. BUUNK* Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague and University of Groningen, The Netherlands (Received: 11 August 2016; accepted: 01 February 2017) Abstract. The present research examined attitudes towards cousin marriages among young people from various ethnic groups living in The Netherlands. The sample consisted of 245 participants, with a mean age of 21, and included 107 Dutch, 69 Moroccans, and 69 Turks. The parents of the latter two groups came from countries where cousin marriages are accepted. Participants reported more negative than positive attitudes towards cousin marriage, and women reported more negative attitudes than did men. The main objection against marrying a cousin was that it is wrong for religious reasons, whereas the risk of genetic defects was considered less important. Moroccans had less negative attitudes than both the Dutch and the Turks, who did not differ from each other. Among Turks as well as among Moroccans, a more positive attitude towards cousin marriage was predicted independently by a preference for parental control of mate choice and religiosity. This was not the case among the Dutch. Discussion focuses upon the differences between Turks and Moroccans, on the role of parental control of mate choice and religiosity, and on the role of incest avoidance underlying attitudes towards cousin marriage. Keywords: cousin marriage, consanguineity, Turks, Moroccans ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGE The large cultural and historical variation in the attitudes towards cousin marriages suggests that there is not a universal, evolved mechanism against mating with cousins (cf. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

The Idea of Virtue in Architecture

17-9-2012 the Theme 2 Craftsmanship: Intelligence and Making, the idea of love in architecture jctv argument Wanda Landowska’s hand in experiential terms words are rather poor In what ways do we capture experience? Pictures and words and all that.. Chengde, Hebei Province, Pule Si Fan Kuan 1000-1031, Travellers Among Streams and Mountains 1 17-9-2012 Tung Chi’i Chang: “Painting is no Someone with a small vocabulary equal to mountains and water for has a small capacity for expressing the wonder of scenery, but his experience in words and a small mountains and water are no equal capacity for processing and to painting for the sheer marvels of nuancing that experience. brush and ink”[1] Someone with a university But this means very little. He is still education, according to research capable of having that experience… done in1995 article has an average vocabulary of 8000 words… He can describe every and any experience, perception, feeling but With this he is able to describe and only on the basis of a selective process his experience. This means process: he selects for his he can only describe his experience description what he finds selectively important and what he has words for 2 17-9-2012 What you cannot capture in words, The whole of his experience is still remains part of your always larger and yet his experience. What does this mean? description is also richer than the It does not mean that words are experience itself, it is received in useless, it means that words the context of the receiver’s cannot be expected to capture experience and appropriated everything of bodily experience. -

Fundamentals of Mathematical Theory of Emotional Robots

Department of Education and Science, Russian Federation Perm State University FUNDAMENTALS OF MATHEMATICAL THEORY OF EMOTIONAL ROBOTS MONOGRAPH Oleg G. Pensky, Kirill V. Chernikov 2010 Perm, RUSSIA Abstract In this book we introduce a mathematically formalized concept of emotion, robot’s education and other psychological parameters of intelligent robots. We also introduce unitless coefficients characterizing an emotional memory of a robot. Besides, the effect of a robot’s memory upon its emotional behavior is studied, and theorems defining fellowship and conflicts in groups of robots are proved. Also unitless parameters describing emotional states of those groups are introduced, and a rule of making alternative (binary) decisions based on emotional selection is given. We introduce a concept of equivalent educational process for robots and a concept of efficiency coefficient of an educational process, and suggest an algorithm of emotional contacts within a group of robots. And generally, we present and describe a model of a virtual reality with emotional robots. The book is meant for mathematical modeling specialists and emotional robot software developers. Translated from Russian by Julia Yu. Plotnikova © Pensky O.G., Chernikov K.V. 2010 2 CONTENTS Introduction 5 1. Robot’s emotion: definition 7 2. Education of a robot 12 3. Parameters of a group of emotional robots 22 4. Friendship between robots: fellowship (concordance) 24 5. Equivalent educational processes 26 5.1. Mathematical model of equivalent education processes 27 5.2. Alternative to an objective function under coincidence of time steps of real and equivalent education processes 29 5.3. Generalization in case of noncoincidence of time steps of real and equivalent education processes 33 6. -

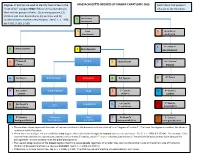

MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES of KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each Title Is That Person’S “Next of Kin” Category ONLY If There Are No Members in Relation to the Decedent

Degrees of kinship are used to identify heirs at law in the MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES OF KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each title is that person’s “next of kin” category ONLY if there are no members in relation to the Decedent. the first four groups of heirs: (1) surviving spouse, (2) children and their descendants, (3) parents, and (4) brothers/sisters and their descendants. See G. L. c. 190B, 4 Great-Great Grandparent §§ 2-102, 2-103, 2-106. 3 Great 5 Great-Great Grandparent Aunt/Uncle 6 1st Cousin of 4 Great Aunt/Uncle 2 Grandparent Grandparent 5 1st Cousin of Parent 3 Aunt/Uncle 7 2nd Cousin of Parent Parent rd 6 2nd Cousin Brother/Sister Decedent 4 1st Cousin 8 3 Cousin 7 2nd Cousin’s Niece/Nephew Child 5 1st Cousin’s 9 3rd Cousin’s Children Children Children 1st Cousin’s 10 3rd Cousin’s 8 2nd Cousin’s Great Grandchild 6 Grandchildren Grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchildren 9 2nd Cousin’s Great-great Great 7 1st Cousin’s 11 3rd Cousin’s Great-grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchild Great-grandchildren Great-grandchildren The numbers above represent the order of nearness in blood to the deceased and are referred to as “degrees of kindred”. The lower the degree or number, the closer a relation is to the Decedent. When there are multiple relations with the same degree, those who claim through the nearest ancestor are preferred. See G. L. c. 190B, § 2-103 (4). For example, if the nearest living relatives are a great-aunt, a great-uncle and two 1st cousins, all are 4th degree relations, but the two 1st cousins inherit because they claim through the grandparents - a closer ancestor than the great-grandparents. -

Perceptions of Polyamory in Canada

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Research Centres, Institutes, Projects and Units Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family 2017-12-01 Perceptions of Polyamory in Canada Boyd, J.-P. E. Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family. Boyd, J.-P. E. (2017). Perceptions of Polyamory in Canada (rep.). Calgary, AB: Canadian Research Institutue for Law and the Family http://hdl.handle.net/1880/107212 report Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca PERCEPTIONS OF POLYAMORY IN CANADA Prepared by: John-Paul E. Boyd, M.A., LL.B. December 2017 Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family Conducting meaningful research since 1987 308.301 14th Street NW, Calgary, AB T2N 2A1 +1.403.216.0340 [email protected] www.crilf.ca The Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family is a non-profit, independent charitable institute affiliated with the University of Calgary. The major goals of the Institute are to undertake and promote interdisciplinary research, education, and publication on issues related to law and the family. The Institute’s mission and vision statement is: The Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family, established in 1987, is the national leader in high-quality, multidisciplinary research on law, the family and children. The Institute seeks to achieve better outcomes for families and children by: • promoting the development and use of evidence-based research; • informing courts, government, professionals, academics, service providers and the public; and, • advising on the development of law, policy, processes and practices. The members of the Institute are: Marie Gordon, QC (President) David Day, QC (Vice-President) Eugene Raponi, QC (Treasurer) Jackie Sieppert (Secretary) Prof. -

Download Article (PDF)

Journal of Robotics, Networking and Artificial Life, Vol. 2, No. 4 (March 2016), 247-251 Dynamic Behavior Selection Model based on Emotional States for Conbe-I robot Wisanu Jitviriya and Jiraphan Inthiam Computer Science and Systems Engineering, Kyushu Institute of Technology. 680-4, Kawazu, Iizuka, Fukuoka, 820-8502, Japan. [email protected], [email protected] Eiji Hayashi Mechanical Information Science and Technology, Kyushu Institute of Technology. 680-4, Kawazu, Iizuka, Fukuoka, 820-8502, Japan. [email protected] Abstract Currently, the rapid development of non-industrial robots that are designed with artificial intelligence (AI) methods to improve the robotics system is to have them imitate human thinking and behavior. Therefore, our works have focused on studying and investigating the application of brain-inspired technology for developing the conscious behavior robot (Conbe-I). We created the hierarchical structure model, which is called “Consciousness-Based Architecture: CBA” module, but it has limitation in managing and selecting the behavior that only depends on the increase and decrease of the motivation levels. Consequently, in this paper, we would like to introduce the dynamic behavior selection model based on emotional states, which develops by Self-organizing map learning and Markov model in order to define the relationship between the behavioral selection and emotional expression model. We confirm the effectiveness of the proposed system with the experimental results. Keywords: Behavior selection model, Self-organizing map (SOM) learning, Markovian model. group. But the conventional (CBA) model has limitation 1. Introduction in managing and selecting the behavior that only Nowadays, the focus of research of service robots is depends on the increase and decrease of the motivation a development of the robots that are able to express levels.