Perceptions of Polyamory in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

All in the Family: Attitudes Towards Cousin Marriages Among Young Dutch People from Various Ethnic Groups

Original Evolution, Mind and Behaviour 15(2017), 1–15 article DOI: 10.1556/2050.2017.0001 ALL IN THE FAMILY: ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGES AMONG YOUNG DUTCH PEOPLE FROM VARIOUS ETHNIC GROUPS ABRAHAM P. BUUNK* Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague and University of Groningen, The Netherlands (Received: 11 August 2016; accepted: 01 February 2017) Abstract. The present research examined attitudes towards cousin marriages among young people from various ethnic groups living in The Netherlands. The sample consisted of 245 participants, with a mean age of 21, and included 107 Dutch, 69 Moroccans, and 69 Turks. The parents of the latter two groups came from countries where cousin marriages are accepted. Participants reported more negative than positive attitudes towards cousin marriage, and women reported more negative attitudes than did men. The main objection against marrying a cousin was that it is wrong for religious reasons, whereas the risk of genetic defects was considered less important. Moroccans had less negative attitudes than both the Dutch and the Turks, who did not differ from each other. Among Turks as well as among Moroccans, a more positive attitude towards cousin marriage was predicted independently by a preference for parental control of mate choice and religiosity. This was not the case among the Dutch. Discussion focuses upon the differences between Turks and Moroccans, on the role of parental control of mate choice and religiosity, and on the role of incest avoidance underlying attitudes towards cousin marriage. Keywords: cousin marriage, consanguineity, Turks, Moroccans ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGE The large cultural and historical variation in the attitudes towards cousin marriages suggests that there is not a universal, evolved mechanism against mating with cousins (cf. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

The Idea of Virtue in Architecture

17-9-2012 the Theme 2 Craftsmanship: Intelligence and Making, the idea of love in architecture jctv argument Wanda Landowska’s hand in experiential terms words are rather poor In what ways do we capture experience? Pictures and words and all that.. Chengde, Hebei Province, Pule Si Fan Kuan 1000-1031, Travellers Among Streams and Mountains 1 17-9-2012 Tung Chi’i Chang: “Painting is no Someone with a small vocabulary equal to mountains and water for has a small capacity for expressing the wonder of scenery, but his experience in words and a small mountains and water are no equal capacity for processing and to painting for the sheer marvels of nuancing that experience. brush and ink”[1] Someone with a university But this means very little. He is still education, according to research capable of having that experience… done in1995 article has an average vocabulary of 8000 words… He can describe every and any experience, perception, feeling but With this he is able to describe and only on the basis of a selective process his experience. This means process: he selects for his he can only describe his experience description what he finds selectively important and what he has words for 2 17-9-2012 What you cannot capture in words, The whole of his experience is still remains part of your always larger and yet his experience. What does this mean? description is also richer than the It does not mean that words are experience itself, it is received in useless, it means that words the context of the receiver’s cannot be expected to capture experience and appropriated everything of bodily experience. -

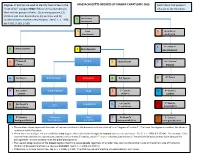

MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES of KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each Title Is That Person’S “Next of Kin” Category ONLY If There Are No Members in Relation to the Decedent

Degrees of kinship are used to identify heirs at law in the MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES OF KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each title is that person’s “next of kin” category ONLY if there are no members in relation to the Decedent. the first four groups of heirs: (1) surviving spouse, (2) children and their descendants, (3) parents, and (4) brothers/sisters and their descendants. See G. L. c. 190B, 4 Great-Great Grandparent §§ 2-102, 2-103, 2-106. 3 Great 5 Great-Great Grandparent Aunt/Uncle 6 1st Cousin of 4 Great Aunt/Uncle 2 Grandparent Grandparent 5 1st Cousin of Parent 3 Aunt/Uncle 7 2nd Cousin of Parent Parent rd 6 2nd Cousin Brother/Sister Decedent 4 1st Cousin 8 3 Cousin 7 2nd Cousin’s Niece/Nephew Child 5 1st Cousin’s 9 3rd Cousin’s Children Children Children 1st Cousin’s 10 3rd Cousin’s 8 2nd Cousin’s Great Grandchild 6 Grandchildren Grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchildren 9 2nd Cousin’s Great-great Great 7 1st Cousin’s 11 3rd Cousin’s Great-grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchild Great-grandchildren Great-grandchildren The numbers above represent the order of nearness in blood to the deceased and are referred to as “degrees of kindred”. The lower the degree or number, the closer a relation is to the Decedent. When there are multiple relations with the same degree, those who claim through the nearest ancestor are preferred. See G. L. c. 190B, § 2-103 (4). For example, if the nearest living relatives are a great-aunt, a great-uncle and two 1st cousins, all are 4th degree relations, but the two 1st cousins inherit because they claim through the grandparents - a closer ancestor than the great-grandparents. -

RAHC Cultural Orientation Handbook Is the First Part of the Training and Orientation Program You Will Undertake

Cultural Orientation Handbook Funded by the Australian Government Photographs used in this handbook were taken in the Northern Territory communities of Ampilatwatja, Ti Tree, Imanpa and Galiwin’ku. Permission was sought from these communities and from all individuals or guardians of individuals, before photography commenced. All photographs are copyright of the Remote Area Health Corps. © Copyright - Remote Area Health Corps, RAHC, 2013 Contents Welcome ..........................................4 Working within the Dying, death and kinship network ...........................27 sorry business .............................. 35 Introduction to this handbook ........................................5 The kinship network Dying Roles and responsibilities Death Your first days .................................7 Avoidance and Poison relationships Sorry business Permits Where do you fit in? Other cultural considerations Forbidden areas and sacred sites When offered a skin name relating to treatment ................ 39 Alcohol Working with the right members Blame and payback Introductions of the kinship network Curses Adjusting to your role Reciprocity — sharing Traditional healers Working with Elders Working within the Use of ochre Aboriginal community ..............11 Birth and childhood .................. 33 Treatment arising from The Aboriginal community Birth ceremonial activity Factionalism and politics Childhood Hair and clothing Engaging with the community Men’s and Women’s business Personal presentation Treatment compliance ............ -

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

EROS AND THE EROS-AFFLICTED: ANCIENT GREEK EROTIC ANXIETY THROUGH THE MYTHS OF HELEN AND MEDEA by CASEY RUTH NEILL (Under the Direction of Charles Platter) ABSTRACT The aim of the thesis is to examine the portrayals of eros, both its perceived origin and effects on the human body, and eros-afflicted women, who might be compelled to act against the established socio-political norm. Helen and Medea are used as a lens through which any potential changes or shifts in Greek thought over time may be identified. The thesis progresses chronologically through time beginning with Homer and concluding in the fourth and third centuries B.C.E. INDEX WORDS: Eros in Ancient Greece; Eros; Women and Eros; Women in the Ancient World; Erotic Desire; Erotic Anxiety; Helen; Medea EROS AND THE EROS-AFFLICTED: ANCIENT GREEK EROTIC ANXIETY THROUGH THE MYTHS OF HELEN AND MEDEA by CASEY RUTH NEILL B.A., Ohio University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 © 2014 Casey Ruth Neill All Rights Reserved EROS AND THE EROS-AFFLICTED: ANCIENT GREEK EROTIC ANXIETY THROUGH THE MYTHS OF HELEN AND MEDEA by CASEY RUTH NEILL Major Professor: Charles Platter Committee: Naomi Norman Christine Albright Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2014 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my parents for their constant stream of support during the composition of this thesis. My father set a strong example of hard work and dedication that I have emulated throughout my academic career. -

Cousins and All That You Can Use This Table to Work out How You Are Related to Another Member of the Family. Firstly You Need To

Cousins and all that You can use this table to work out how you are related to another member of the family. Firstly you need to work out who the common direct ancestor is, that is the person who is in both your direct lines. Then you work out how you are both related to that person. If they are your great grandparent, you follow down that column. If they are your relative’s parent, they follow across the parent row. The box where your column and their row meet shows your relationship: you are this person’s great niece or nephew. If they follow the columns and you follow the rows, it will also show that they are your great aunt or uncle. Common Parent Grandparent Great x2 great grandparent x3 great x4 great grandchild ancestor grandparent grandparent Parent Child Niece/nephew Great x2 great niece/nephew x3 great x4 great niece/nephew niece/nephew niece/nephew Grandparent Aunt/uncle 1st cousin 1st cousin once 1st cousin twice 1st cousin x3 1st cousin x4 removed removed removed removed Great Great 1st cousin once 2nd cousin 2nd cousin once 2nd cousin twice 2nd cousin x3 removed grandparent aunt/uncle removed removed removed x2 great x2 great 1st cousin twice 2nd cousin one 3rd cousin 3rd cousin once 3rd cousin twice removed grandparent aunt/uncle removed removed removed x3 great x3 great 1st cousin x3 2nd cousin twice 3rd cousin once 4th cousin 4th cousin once removed grandparent uncle/aunt removed removed removed x4 great x4 great 1st cousin x4 2nd cousin x3 3rd cousin x2 removed 4th cousin once 5th cousin grandparent uncle/aunt removed removed removed CousinsAndAllThat 2014 Jane Harris www.janealogy.co.uk Examples An easy one to start! I see someone posting a message wanting to find relatives of his grandfather John’s sister Mary. -

The Family Lifestyle in Nigeria

THE FAMILY LIFESTYLE IN NIGERIA By Morire OreOluwapo LABEODAN School of Statistics and Actuarial Science University of the Witwatersrand Private Bag 3, Wits 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa. Email Address: [email protected] [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Nigeria families are patriarchal with extended family members having more say than usual in comparison to family setups in the westernized world. Although children are very important to Nigeria families because parents believe that their children will provide support for them in their old age, family relationships are mostly guided by strict system of ‘seniority’ and male tended egoistic values. Emphasis has always been placed on male members of the family more because of their rights to both family inheritance and extension of family lineage and name. Embedded in the family system are social norms passed down from one generation to another. Most of these societal norms cut across the nation irrespective of age, educational achievement, religion, marital status and so on. With the gradual introduction of western lifestyle and religious virtues, one is interested in knowing if the Nigeria lifestyle trend is still the same. This was a trial study that examined the Nigeria family lifestyle with emphasis on the South West population of the country, who are generally referred to as ‘Yorubas’. Case studies of people interviewed were examined and reviewed based on the author’s opinion and certain defined criterias. The cases were classified using both Africa (Nigeria) and westernized virtues as being blessing, if the lifestyle benefits the individual, curse, if the lifestyle does not benefit the individual, and mixed blessing if it is a fifty percent chance in both ways. -

114 2. Unilateral Cross-Cousin Marriage

114 2. Unilateral Cross-Cousin Marriage : Some Observations on the Controversy SATYA P. SHARMA University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada I. THERE IS a large body of literature in social anthropology centering around the controversy over the significance of unilateral cross-cousin marriage. The implications of the arguments in this controversy do not simply concern as to "whether one can be (or should be) forced to marry his patrilateral cross- cousin" (Murphy 1963: 18), but, as Schneider (1965) and Maybury-Lewis (1965) have indicated, there are fundamental theoretical and methodological issues at stake. Indeed, the debate on this topic raises most of the important issues entailed in anthropological explanation in general, and in causal versus functional explanations in particular (Spiro 1964: 30). One of the basic questions in the controversy is : given unilateral cross- cousin marriage, why does matrilateral cross-cousin marriage (hereafter mccm) occur more frequently than patrilateral cross-cousin marriage (hereafter pccm) ? Two main concepts are also central to the argument: (1) the distinc- tion between preferential and prescriptive marriage; and (2) the differential solidarity consequences of mccm and pccm. In this paper I will briefly examine Ldvi-Strauss's (hereafter LS) thesis on cross-cousin marriage (hereafter ccm) as initially presented in his Les Structures Élémentaires de la Parenti ( 1949) . I will then review Homans and Schneider's criticism of LS as presented in Marriage, Authority and Final Causes (1955) in which they rejected LS's structural analysis of the ccm problem and offered a psychological explanation in its place. Needham's Structure and Sentiment ( 1962), an extended critique of Homans and Schneider's thesis, in which Needham has attempted to reiterate LS's argument, will be examined next. -

Family Structures

Métis Family Life – Leah Dorion Module Objective: In this module, the students will learn how Métis families have oriented themselves since the beginnings of the fur trade to the present. The students will also learn why genealogy is so important to Métis families and individuals. Métis Family Life: An Overview Family Life is very important to the Métis. Family relations have in fact always been important to the Métis, especially given their mixed ancestry. At first, this made Métis family life and family values very complicated since the Métis had various First Nations, French-Canadian, Scots, Orkney and English relatives. Often, relations between the parent groups and even their Métis children were not always cordial. It was only when the Métis population grew and the Métis began to intermarry other Métis, that the Métis family really developed. Métis intermarriage or endogamy was practiced largely because the mixed heritage offspring of First Nations, Europeans and Euro-Canadians felt themselves different from their parent groups and similar to each other that they preferred intermarriage. Métis intermarriage remains the most common form of marriage among the Métis. 1 Traditionally, it has been maintained by historians, archaeologists and social scientists that the Métis were a mere byproduct of the great continental fur trade, which led to the birth of European Canada. The Métis were said to have been the result of liaisons, often illicit, between willing First Nations women and female- starved European adventurers. Of course, while the Métis emerged as a people largely as a result of the fur trade, they, nevertheless, developed their own group cohesion, which often proved contradictory to the aspirations of their fur trade fathers or their First Nations relatives.