114 2. Unilateral Cross-Cousin Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Lineal Kinship Organization in Cross-Specific Perspective

Lineal kinship organization in cross-specific perspective Laura Fortunato Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology University of Oxford 64 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6PN, UK [email protected] +44 (0)1865 284971 Santa Fe Institute 1399 Hyde Park Road Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA Published as: Fortunato, L. (2019). Lineal kinship organization in cross-specific perspective. Philo- sophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 374(1780):20190005. http: //dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0005, The article is part of the theme issue \The evolution of female-biased kinship in humans and other mammals". http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb/374/1780. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Kinship vs. descent 5 3 Lineal kinship in cross-specific perspective 8 4 Lineal kinship in cross-cultural perspective 12 4.1 A cross-cultural example: the association between descent and residence . 13 4.2 Reframing lineal kinship organization as lineal biases in kin investment . 19 5 Conclusion 21 References 23 2 Abstract I draw on insights from anthropology to outline a framework for the study of kinship systems that applies across animal species with biparental sexual reproduction. In particular, I define lineal kinship organization as a social system that emphasizes interactions among lineally related kin | that is, individuals related through females only, if the emphasis is towards matrilineal kin, and individuals related through males only, if the emphasis is towards patrilineal kin. In a given population, the emphasis may be expressed in one or more social domains, corresponding to pathways for the transmission of different resources across generations (e.g. -

Gender, Ritual and Social Formation in West Papua

Gender, ritual Pouwer Jan and social formation Gender, ritual in West Papua and social formation A configurational analysis comparing Kamoro and Asmat Gender,in West Papua ritual and social Gender, ritual and social formation in West Papua in West ritual and social formation Gender, This study, based on a lifelong involvement with New Guinea, compares the formation in West Papua culture of the Kamoro (18,000 people) with that of their eastern neighbours, the Asmat (40,000), both living on the south coast of West Papua, Indonesia. The comparison, showing substantial differences as well as striking similarities, contributes to a deeper understanding of both cultures. Part I looks at Kamoro society and culture through the window of its ritual cycle, framed by gender. Part II widens the view, offering in a comparative fashion a more detailed analysis of the socio-political and cosmo-mythological setting of the Kamoro and the Asmat rituals. These are closely linked with their social formations: matrilineally oriented for the Kamoro, patrilineally for the Asmat. Next is a systematic comparison of the rituals. Kamoro culture revolves around cosmological connections, ritual and play, whereas the Asmat central focus is on warfare and headhunting. Because of this difference in cultural orientation, similar, even identical, ritual acts and myths differ in meaning. The comparison includes a cross-cultural, structural analysis of relevant myths. This publication is of interest to scholars and students in Oceanic studies and those drawn to the comparative study of cultures. Jan Pouwer (1924) started his career as a government anthropologist in West New Guinea in the 1950s and 1960s, with periods of intensive fieldwork, in particular among the Kamoro. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Post-Marital Residence, Delineations of Kin, and Social Support Among South Indian Tamils

Cooperation beyond consanguinity: Post-marital residence, delineations of kin, and social support among South Indian Tamils Eleanor A. Power1 &ElspethReady2 1Department of Methodology, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, UK 2Department of Human Behavior, Ecology and Culture, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, 04103, Germany February 28, 2019 Abstract Evolutionary ecologists have shown that relatives are important providers of support across many species. Among humans, cultural reckonings of kinship are more than just relatedness, as they interact with systems of descent, inheritance, marriage, and residence. These cultural aspects of kinship may be particularly important when a person is deter- mining which kin, if any, to call upon for help. Here, we explore the relationship between kinship and cooperation by drawing upon social support network data from two villages in South India. While these Tamil villages have a nominally male-biased kinship system (being patrilocal and patrilineal), matrilateral kin play essential social roles and many women reside in their natal villages, letting us tease apart the relative importance of ge- netic relatedness, kinship, and residence in accessing social support. We find that people often name both their consanguineal and affinal kin as providing them with support, and we see some weakening of support with lesser relatedness. Matrilateral and patrilateral relatives are roughly equally likely to be named, and the greatest distinction instead is in their availability, which is highly contingent on post-marital residence patterns. People residing in their natal village have many more consanguineal relatives present than those who have relocated. Still, relocation has only a small e↵ect on an individual’s network size, as non-natal residents are more reliant on the few kin that they have present, most of whom are affines. -

All in the Family: Attitudes Towards Cousin Marriages Among Young Dutch People from Various Ethnic Groups

Original Evolution, Mind and Behaviour 15(2017), 1–15 article DOI: 10.1556/2050.2017.0001 ALL IN THE FAMILY: ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGES AMONG YOUNG DUTCH PEOPLE FROM VARIOUS ETHNIC GROUPS ABRAHAM P. BUUNK* Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague and University of Groningen, The Netherlands (Received: 11 August 2016; accepted: 01 February 2017) Abstract. The present research examined attitudes towards cousin marriages among young people from various ethnic groups living in The Netherlands. The sample consisted of 245 participants, with a mean age of 21, and included 107 Dutch, 69 Moroccans, and 69 Turks. The parents of the latter two groups came from countries where cousin marriages are accepted. Participants reported more negative than positive attitudes towards cousin marriage, and women reported more negative attitudes than did men. The main objection against marrying a cousin was that it is wrong for religious reasons, whereas the risk of genetic defects was considered less important. Moroccans had less negative attitudes than both the Dutch and the Turks, who did not differ from each other. Among Turks as well as among Moroccans, a more positive attitude towards cousin marriage was predicted independently by a preference for parental control of mate choice and religiosity. This was not the case among the Dutch. Discussion focuses upon the differences between Turks and Moroccans, on the role of parental control of mate choice and religiosity, and on the role of incest avoidance underlying attitudes towards cousin marriage. Keywords: cousin marriage, consanguineity, Turks, Moroccans ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGE The large cultural and historical variation in the attitudes towards cousin marriages suggests that there is not a universal, evolved mechanism against mating with cousins (cf. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

The Idea of Virtue in Architecture

17-9-2012 the Theme 2 Craftsmanship: Intelligence and Making, the idea of love in architecture jctv argument Wanda Landowska’s hand in experiential terms words are rather poor In what ways do we capture experience? Pictures and words and all that.. Chengde, Hebei Province, Pule Si Fan Kuan 1000-1031, Travellers Among Streams and Mountains 1 17-9-2012 Tung Chi’i Chang: “Painting is no Someone with a small vocabulary equal to mountains and water for has a small capacity for expressing the wonder of scenery, but his experience in words and a small mountains and water are no equal capacity for processing and to painting for the sheer marvels of nuancing that experience. brush and ink”[1] Someone with a university But this means very little. He is still education, according to research capable of having that experience… done in1995 article has an average vocabulary of 8000 words… He can describe every and any experience, perception, feeling but With this he is able to describe and only on the basis of a selective process his experience. This means process: he selects for his he can only describe his experience description what he finds selectively important and what he has words for 2 17-9-2012 What you cannot capture in words, The whole of his experience is still remains part of your always larger and yet his experience. What does this mean? description is also richer than the It does not mean that words are experience itself, it is received in useless, it means that words the context of the receiver’s cannot be expected to capture experience and appropriated everything of bodily experience. -

Susan Rodgers Sire Gar in a Gathering of Batak Village Grandmothers In

A BATAK LITERATURE OF MODERNIZATION* Susan Rodgers Sire gar In a gathering of Batak village grandmothers in my house in 1976 to tape record some traditional ritual speech, one old ompu* 1 took the time to survey the changes in Batak kinship she had witnessed in her lifetime. Like many of her contemporar ies, she spoke warmly of the "more orderly" kinship world of her childhood, when people "still married who they should." She contrasted this halcyon age to present- day conditions: young people were marrying against the grain of the adat, house holds were ignoring their adat obligations to lend labor assistance to relatives in favor of concentrating on their own fields and farmwork, and her neighbors were beginning to forget some of the courtly eulogistic terms once used in addressing kinsmen. Fixing me with a stare and breaking out of her customary Angkola Batak2 into Indonesian, she delivered a final withering epithet on modern-day Batak family life: just one quality characterized it, "Merdeka di segala-gala--Freedom in every thing! " Change in the Angkola Batak kinship system in the last seventy to eighty years has indeed been considerable. Many of these changes have been reflected in Batak literature, which, in turn, has influenced the process. In fact, Batak oral and written literature has served the Batak as a medium for reformulating their kinship system in a time of rapid educational improvements, migration out of the ethnic homelands, and increasing contact with other ethnic societies and Indonesian nation al culture. In this paper I would like to investigate the relationship between Angkola Batak kinship and its locally authored literature as the society has modernized, fo cusing in particular on the subjects of courtship and marriage. -

The Aspirational Facet of Kinship Talk During Times Of

bs_bs_banner Life during wartime: aspirational kinship and the management of insecurity Mike McGovern University of Michigan This article explores the ways that the institution of the avunculate has been used as an idiom for negotiating forced displacement, dispossession, and insecurity in the forested region where modern-day Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Côte d’Ivoire converge. The essay analyses the ways that the rights and responsibilities that inhere in the MB-ZS relationship are both invoked ‘aspirationally’ by those with no prior link of kinship and parried by those who should in principle be bound by them. This degree of play suggests that the avunculate in this region is best understood as one of several idioms used to legitimate claims made on others, often in times of uncertainty and instability. Rather than treat this relationship as an always-already existing social institution, the article suggests that it is also the product of a historical experience of persistent warfare, displacement, and flight. How does a refugee manage her arrival in a village where she knows no one? When talking with Loma-speakers in southeastern Guinea about the ways that people are related to one another, men in particular often refer to the institution of Mother’s Brother-Sister’s Son (keke-daabe) relations to explain their mutual rights and respon- sibilities. However, as I describe below, these ostensible rights and responsibilities are flouted or cancelled out as often as they are respected. Meanwhile, the stranger arriving in a new village might at first seem to be excluded from such pre-existing relations. -

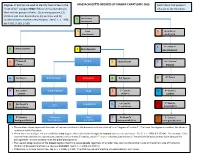

MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES of KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each Title Is That Person’S “Next of Kin” Category ONLY If There Are No Members in Relation to the Decedent

Degrees of kinship are used to identify heirs at law in the MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES OF KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each title is that person’s “next of kin” category ONLY if there are no members in relation to the Decedent. the first four groups of heirs: (1) surviving spouse, (2) children and their descendants, (3) parents, and (4) brothers/sisters and their descendants. See G. L. c. 190B, 4 Great-Great Grandparent §§ 2-102, 2-103, 2-106. 3 Great 5 Great-Great Grandparent Aunt/Uncle 6 1st Cousin of 4 Great Aunt/Uncle 2 Grandparent Grandparent 5 1st Cousin of Parent 3 Aunt/Uncle 7 2nd Cousin of Parent Parent rd 6 2nd Cousin Brother/Sister Decedent 4 1st Cousin 8 3 Cousin 7 2nd Cousin’s Niece/Nephew Child 5 1st Cousin’s 9 3rd Cousin’s Children Children Children 1st Cousin’s 10 3rd Cousin’s 8 2nd Cousin’s Great Grandchild 6 Grandchildren Grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchildren 9 2nd Cousin’s Great-great Great 7 1st Cousin’s 11 3rd Cousin’s Great-grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchild Great-grandchildren Great-grandchildren The numbers above represent the order of nearness in blood to the deceased and are referred to as “degrees of kindred”. The lower the degree or number, the closer a relation is to the Decedent. When there are multiple relations with the same degree, those who claim through the nearest ancestor are preferred. See G. L. c. 190B, § 2-103 (4). For example, if the nearest living relatives are a great-aunt, a great-uncle and two 1st cousins, all are 4th degree relations, but the two 1st cousins inherit because they claim through the grandparents - a closer ancestor than the great-grandparents.