The Evolution of a British Columbian Forest Landscape, As Observed in the Soo Public Sustained Yield Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia Geological Survey Geological Fieldwork 1989

GEOLOGY AND MINERAL OCCURRENCES OF THE YALAKOM RIVER AREA* (920/1, 2, 92J/15, 16) By P. Schiarizza and R.G. Gaba, M. Coleman, Carleton University J.I. Garver, University of Washington and J.K. Glover, Consulting Geologist KEYWORDS:Regional mapping, Shulaps ophiolite, Bridge REGIONAL GEOLOGY River complex, Cadwallader Group Yalakom fault, Mission Ridge fault, Marshall Creek fault. The regional geologic setting of the Taseko-Bridge River projectarea is described by Glover et al. (1988a) and Schiarizza et al. (1989a). The distributicn and relatio~uhips of themajor tectonostratigraphic assemblages are !;urn- INTRODUCTION marized in Figures 1-6-1 ;and 1-6-2. The Yalakom River area covers about 700 square kilo- The Yalakom River area, comprisinl: the southwertem metres of mountainous terrain along the northeastern margin segment of the project area, encompasses the whole OF the of the Coast Mountains. It is centred 200 kilometres north of Shubdps ultramafic complex which is interpreted by hagel Vancouver and 35 kilometresnorthwest of Lillooet.Our (1979), Potter and Calon et a1.(19901 as a 1989 mapping provides more detailed coverageof the north- (1983, 1986) dismembered ophiolite. 'The areasouth and west (of the em and western ShulapsRange, partly mapped in 1987 Shulaps complex is underlain mainly by Cjceanic rocks cf the (Glover et al., 1988a, 1988b) and 1988 (Schiarizza et al., Permian(?)to Jurassic €!ridge Rivercomplex, and arc- 1989d, 1989b). and extends the mapping eastward to include derived volcanic and sedimentary rocksof the UpperTri %sic the eastem part of the ShulapsRange, the Yalakom and Cadwallader Group. These two assemhkgesare struclurally Bridge River valleys and the adjacent Camelsfoot Range. -

Community Risk Assessment

COMMUNITY RISK ASSESSMENT Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Abstract This Community Risk Assessment is a component of the SLRD Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan. A Community Risk Assessment is the foundation for any local authority emergency management program. It informs risk reduction strategies, emergency response and recovery plans, and other elements of the SLRD emergency program. Evaluating risks is a requirement mandated by the Local Authority Emergency Management Regulation. Section 2(1) of this regulation requires local authorities to prepare emergency plans that reflects their assessment of the relative risk of occurrence, and the potential impact, of emergencies or disasters on people and property. SLRD Emergency Program [email protected] Version: 1.0 Published: January, 2021 SLRD Community Risk Assessment SLRD Emergency Management Program Executive Summary This Community Risk Assessment (CRA) is a component of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District (SLRD) Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan and presents a survey and analysis of known hazards, risks and related community vulnerabilities in the SLRD. The purpose of a CRA is to: • Consider all known hazards that may trigger a risk event and impact communities of the SLRD; • Identify what would trigger a risk event to occur; and • Determine what the potential impact would be if the risk event did occur. The results of the CRA inform risk reduction strategies, emergency response and recovery plans, and other elements of the SLRD emergency program. Evaluating risks is a requirement mandated by the Local Authority Emergency Management Regulation. Section 2(1) of this regulation requires local authorities to prepare emergency plans that reflect their assessment of the relative risk of occurrence, and the potential impact, of emergencies or disasters on people and property. -

Joffre Lakes Is a Wilderness Area

Camping Ethics Safety Wilderness campsites with a pit toilet are provided at Upper Joffre Lakes is a wilderness area. Be prepared for sudden- Joffre Lakes Joffre Lake. Camp only in designated area. changes in the weather. Carry sufficient food and water and be Campfires are not permitted in the park. Carry a portable informed before entering the backcountry. stove for cooking. Trails in the park are rough and very steep. Alpine areas are Water from lakes, streams and creeks should be boiled very fragile. Take care when hiking and stay on the marked PROVINCIAL PARK for at least two minutes. trails. Do not use soap or detergents in lakes or creeks to Only experienced and equipped mountaineers should prevent contamination. Wash 30 metres away from any attempt mountain climbing or venture out onto glaciers and water source. snow fields. Keep a clean campsite and pack out what you pack in. Leave a trip plan, including route to be taken, destination Cook and store food 100 metres from your campsite. and expected time of return, with a reliable contact. Consumption of alcoholic beverages is prohibited in A pay telephone is located at Mount Currie, 22 kilometres west provincial parks, except in your campsite. on Duffey Lake Road. Cell phone range begins at Lillooet Lake. Pets should not be taken into this wilderness area. They must be kept on a leash and under control at all times. Things to Do A steep trail leads from Lower Joffre Lake to Middle and Upper Joffre lakes. Views of the surrounding mountain peaks and icefields can be enjoyed along the length ofthe trail. -

Duffey Lake Provincial Park

Duffey Lake Provincial Park M ANAGEMENT LAN P Prepared by: Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks BC Parks, Garibaldi/Sunshine Coast District Brackendale, B.C. in conjunction with: Ministry of Environment, Terra Firma Environmental Consultants Lands and Parks BC Parks Division Duffey Lake Provincial Park M ANAGEMENT LAN P PARK VISION Duffey Lake Park will continue to be an important part of the parks system on both a regional and provincial level. While the park is relatively small, its key habitat components, unique setting in the transition zone between the coast mountains and the dry interior, and recreational opportunities will make this area a favourite for both destination visitors and the travelling public. Should resource and rural development increase in nearby areas, Duffey Lake Park’s varied habitats for bear, deer, goats, raptors and other wildlife, particularly on the north-west side, will become even more important in providing wildlife the necessary food, cover and shelter to sustain populations in the region. The park will continue to have high water quality, sustained fish populations and together with the wetland habitats, continue to be a high quality aquatic ecosystem. Duffey Lake Park will continue to be important for First Nation traditional use and cultural values. BC Parks, together with the First Nation’s communities, will ensure that significant cultural sites within the park are protected from development impacts and that recreation activities in the park are respectful of the environment and First Nation traditional use. Visitors to the park will be attracted to the low-impact recreational opportunities including day-use and multi-day activities. -

BC Geological Survey Assessment Report 33637

2012 PROSPECTING REPORT FEB 2 2 /ui3 ON THE BIRKEN 3-8 CLAIMS L IN THE PACIFIC RANGES OF THE COAST MOUNTAINS 92 J/7 AND 92 J/10 LILLOOET MINING DIVISION 50 DEGREES 30 MINUTES 14 SECONDS NORTH 122 DEGREES 36 MINUTES 28 SECONDS WEST CLAIMS: BIRKEN 3-8 TENURE NUMBERS: 940489, 940509, 940510, 940513, 940514, 940515 OWNER/OPERATOR: KEN MACKENZI AUTHOR: KEN MACKENZIE, FMC# 1164ffl)fe r SQUAMISH, B.C. EVENT NUMBER: 5424661 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE PAGE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 2 MAP#1 INDEX MAP PAGE 3 MAP #2 BIRKEN 3-8 CLAIMS MAP PAGE 4 MAP # 3 PLACE NAMES PAGE 5 INTRODUCTION PAGE 6 HISTORY OF THE BIRKEN 3-8 CLAIMS PAGE 9 MAP # 4 2011 PROSPECTING TRAVERSE (HISTORY) PAGE 12 HISTORICAL ANALYSIS RESULTS PAGE 13 SUMMARY OF WORK PERFORMED IN 2012 PAGE 18 CONCLUSION PAGE 37 MAP # 5 TRAVERSES AND AREAS PROSPECTED PAGE 38 MAP #6 SIGNIFICANT RESULTS PAGE 39 ITEMIZED COST STATEMENT PAGE 40 APPENDIX "A" AUTHOR'S QUALIFICATIONS PAGE 41 APPENDIX "B" ANALYSIS RESULTS FOR 2012 PAGE 43 2- MineralTitles •Ii""'".!L Online Fort St. John Terrace Quesnel W;Iilams Lake Revel stoxe Vernon Vancouver' Trail _yjctariaL__„ Legend • Indian Reserves • National Parks |—, Conservancy Areas • Parks p Federal Transfer Lands Mineral Tenure (current) Q Minora! Claim PI Mineral Lease Mineral Reserves (current) [•-•] Placer Claim Designation r-j Placer Lease Designation p No Staking Reserve |—| Conditional Reserve I—| Release Required Reserve • Surface Restriction Q Recreation Araa • Others p First Nations Treaty Related Lands |—| First Nations Treaty Lands P Survey Parcels • BCGS Grid Contours (1:25DK) Contour - Index Contour - Intermediate ,, Areaof Exclusion Areaof Indefinite Contours Annotation (1:250K) Transportation - Points (1:250K) Airfield . -

Squamish-Lillooet Regional District

SLRD Regular Meeting Agenda February 22, 2010; 10:30 AM SLRD Boardroom 1350 Aster Street, Pemberton BC Item Item of Business and Recommended Action Page Action Info 1 Call to Order 2 Approval of Agenda 3 Committee Reports and Recommendations 3.1 Committee of the Whole Recommendations of January 26, 2010: n/a 2010 – 2014 Draft Financial Plan: 1. Treaty Advisory PLTAC (1600) THAT the PLTAC Treaty Advisory budget be approved as circulated. 2. Treaty Advisory LMTAC (1601) THAT the LMTAC Treaty Advisory budget be approved as circulated. 3. Gold Bridge Community Complex (2107) THAT the Gold Bridge Community Complex budget be approved as circulated. 4. Sea to Sky Economic Development (3101) THAT the Sea to Sky Economic Development cost centre be renamed to Economic Development; and that $5000 be included in the Economic Development budget. THAT up to $5000 be allocated from the Feasibility Studies fund to facilitate discussions concerning feasibility of a regional economic development service. 5. General Government Services (1000) THAT the General Government budget be approved as circulated. 6. Regional Growth Strategy (1201) THAT the Regional Growth Strategy budget be approved as circulated. SLRD Regular Meeting Agenda - 2 - February 22, 2010 Item Item of Business and Recommended Action Page Action Info 7. Solid Waste Management Planning (1300) THAT the Solid Waste Management Planning budget be approved as circulated. 3.2 Pemberton Valley Utilities & Services Committee n/a Recommendations of January 21, 2010: 1. Memorandum of Understanding Regarding the Pemberton Festival THAT the Memorandum of Understanding Regarding the Pemberton Festival with revisions to Sections 7, 10, 11 and 12 be recommended to the board for approval. -

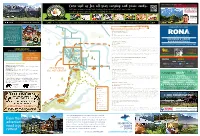

Connection Call 604-230-8167 [email protected] Frankingham.Com

YOUR PEMBERTON Real Estate connection Call 604-230-8167 [email protected] FrankIngham.com FRANK INGHAM GREAT GOLF, FANTASTIC FOOD, EPIC VIEWS. EVERYONE WELCOME! R E A L E S T A T E Pemberton Resident For Over 20 Years 604-894-6197 | pembertongolf.com | 1730 Airport RD Relax and unwind in an exquisite PEMBERTON VALLEY yellow cedar log home. Six PEMBERTON & AREA HIKING TRAILS unique guest bedrooms with private bathrooms, full breakfast ONE MILE LAKE LOOP 1 and outdoor hot tub. Ideal for 1.45km loop/Approx. 30 minutes groups, families and corporate Easy retreats. The Log House B&B 1.3km / 1 minute by vehicle from Pemberton Inn is close to all amenities and PEMBERTON LOCAL. INDEPENDENT. AUTHENTIC. enjoys stunning mountain views. MEADOWS RD. Closest to the Village, the One Mile Lake Loop Trail is an easy loop around the lake that is wheelchair accessible. COLLINS RD. Washroom facilities available at One Mile Lake. HARDWARE & LUMBER 1357 Elmwood Drive N CALL: 604-894-6000 LUMPY’S EPIC TRAIL 2 BUILDING MATERIALS EMAIL: [email protected] 9km loop/ Approx. 4 hours WEB: loghouseinn.com Moderate 7426 Prospect street, Pemberton BC | 604 894 6240 URDAL RD. 1.3km / 1 minute by vehicle from Pemberton The trail is actually a dedicated mountain bike trail but in recent years hikers and mountain runners have used it to gain PROSPECT ST. access to the top of Signal Hill Mountain. The trail is easily accessed from One Mile Lake. Follow the Sea to Sky Trail to EMERGENCIES: 1–1392 Portage Road IN THE CASE OF AN EMERGENCY ALWAYS CALL 911 URCAL-FRASER TRAIL Nairn Falls and turn left on to Nairn One Mile/Lumpy’s Epic trail. -

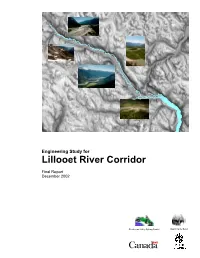

LILLOOET RIVER CORRIDOR Submission of Final Report Our File713.002

EngineeringStudyfor LillooetRiverCorridor FinalReport December2002 PembertonValleyDykingDistrict MountCurrieBand December 23, 2002 Mr. John Pattle, P.Eng. B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection 10470 - 152nd Street Surrey, B.C. V3R 0Y3 Dear Mr. Pattle: RE: ENGINEERING STUDY FOR LILLOOET RIVER CORRIDOR Submission of Final Report Our File713.002 We are pleased to submit 3 copies of the Engineering Study for Lillooet River Corridor Final Report. This report presents current conditions and up-to-date hydraulic modelling results, with a backdrop of historical data and analysis of long-term geomorphological changes within the Pemberton Valley. This report will assist the Steering Group, and communities at large, in understanding and documenting the problem areas. Further, this report will form the foundation of a flood mitigation and management plan for the Pemberton Valley. We have very much enjoyed working on this project with you, and hope we can be of service to you again. We trust this is satisfactory. Yours truly, KERR WOOD LEIDAL ASSOCIATES LTD. Jonathon Ng, P.Eng., PMP Project Manager JN/am Encl. (3) P:\0700-0799\713-002\Report\TransLETTER.doc Engineering Study for Lillooet River Corridor Final Report December 2002 KWL File No. 713.002 ENGINEERING STUDY FOR LILLOOET RIVER CORRIDOR FINAL REPORT PEMBERTON VALLEY DYKING DISTRICT DECEMBER 2002 MOUNT CURRIE BAND STATEMENT OF LIMITATIONS This document has been prepared by Kerr Wood Leidal Associates Ltd. (KWL) for the exclusive use and benefit of the Mount Currie Band, the Pemberton Valley Dyking District, B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Public Works and Government Services Canada, and Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. -

Community Emergency Plan Ponderosa

Community Emergency Plan Ponderosa Table of Contents Key definitions .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Community Overview ................................................................................................................................... 5 Demographics .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Critical infrastructure ............................................................................................................................... 5 Response Capabilities .............................................................................................................................. 6 Hazard, Risk and Evacuation ........................................................................................................................ 7 Evacuation Routes .................................................................................................................................... 7 Interface Fire ........................................................................................................................................... -

Hiking Whistler and Area

Hiking Whistler and Area Trail Name Level Distance & Time Description Just 16 km south of Whistler on Highway 99, Brandywine Falls Provincial Park is home 1 km roundtrip to a spectacular 66 m waterfall and gorgeous views of Daisy Lake and Black Tusk, the Brandywine Falls Easy No elevation gain soaring monolithic remains of a dormant volcano. From the parking lot follow the trail Allow 30 minutes along Brandywine Creek to the railroad track and the observation platform, and enjoy the view! As you head south on Highway 99 from the Village, turn left at the Function Junction traffic lights. Less than 1 kilometer from the lights take a left on to East Side Main Cheakamus Lake 8 -14 km roundtrip logging road. Follow this gravel road for approximately 7 km to the parking lot at the Trail Easy No elevation gain trailhead. The trail is well defined. You can also bike or canoe-portage to the lake on this 4x4 vehicle Allow 5 hours trail. Another worthwhile hiking opportunity is to explore the Whistler Interpretive Forest, recommended found on the left hand side of the road as you turned off Hwy 99. Season: May to November. NO DOGS ALLOWED IN GARIBALDI PARK. Take Highway 99 north from the Village for approximately 25 minutes towards the town of Pemberton to Nairn Falls Provincial Park on the right. Following the trail from the parking lot, this easy path skirts the Green River as it winds through this traditional 3 km roundtrip Lil’Wat travel route and spiritual area. As you are surrounded by Western Hemlock, Red Nairn Falls Easy No elevation gain Cedars and Douglas Fir, keep an eye on the ground for the rubber boa snake, the Allow 1 hour smallest of the boa family and the most cold-tolerant species of snake. -

Helios Tourism Planning Group - I - 4.1.2 Assessment of Newly Established and Proposed Protected Areas

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................ i Preface -........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Part 1 – Introduction & Area Profile .......................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Background & Study Rationale .......................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Study Purpose...................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Methods .............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2.1 Study Limitations......................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 General Area Profile .......................................................................................................................... 8 1.3.1 Management Jurisdictions......................................................................................................... 11 1.3.2 Area-based Access .................................................................................................................... 12 1.4 Nature-Based Tourism Profile......................................................................................................... -

Sea-To-Sky Land and Resource Management Plan Frontcountry Zone Visual Landscape Inventory Contract # 1005 – 40/FS DSQ 2006-02 VQO

Sea-to-Sky Land and Resource Management Plan Frontcountry Zone Visual Landscape Inventory Contract # 1005 – 40/FS DSQ 2006-02 VQO Conducted by: Kenneth B. Fairhurst, R.P.F. RDI Resource Design Inc. www.1rdi.com Submitted March 30, 2006 Contents 1. Summary, Recommendations, and Conclusions................................................................3 2. Introduction...........................................................................................................................7 3. Procedures.......................................................................................................................... 12 4. Findings.............................................................................................................................. 17 Appendix 1 – Standards........................................................................................................ 27 Appendix 2: List of VSUs..................................................................................................... 34 Appendix 3 VSU Attributes................................................................................................. 38 Appendix 4 VSU Classification Forms (under separate cover) ........................................ 42 Appendix 5 Viewpoints – Video Records .......................................................................... 43 Appendix 6 Conference Exposure........................................................................................ 50 Appendix 6 Conference Exposure.......................................................................................