Authentic Recipes from Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern European and Cypriot Cuisine

InterNapa College – Course Information Modern European & Cypriot Cuisine Course Title Modern European & Cypriot Cuisine Course Code TCUA-202 Course Type This course serves as both Elective and Requirement, according to the program. Culinary Diploma/Higher Diploma Requirement All Programs General Elective Level Diploma (Short Cycle) Year / Year 2, A’ Semester Semester Teacher’s Marinos Kyriakou Name ECTS 6 Lectures / week Laboratories / week 5 Course Purpose and This course covers European cuisine and exposes the student to culture, history, diversity Objectives in foods, and flavour profiles from around the world with special reference to the Cyprus cuisine. Upon completion of this course students will be able to: Learning Outcomes 1. Understand the influences and the cultural history on the foods and cuisine of the various countries. 2. Identify factors that influence eating patterns in a country with special reference in Cyprus. 3. Examine foods that are made in various parts of the world and differentiate among the varying cuisines of the world. 4. Demonstrate the various methods of cooking in the international cuisine. 5. Plan and prepare meals from the international cuisine, using various methods of cooking. 6. Demonstrate knowledge of Cyprus cuisine terms and menu construction and obtain skills in Cyprus food preparation (appetizers, main courses and desserts). Prerequisites TCUA – 100 Introduction to Gastronomy & Culinary Theory Required InterNapa College – Course Information Course 1. Cuisine and foods of Cyprus and Europe. Content 2. Preparing buffet displays covering food and pastry items of the European Cuisine. Appetizers, main courses and desserts and buffet preparations. 3. Cooking methods. Different spices and herbs that are recognized as the major representative of each country’s cuisine. -

Herbs, Spices and Flavourings Ebook, Epub

HERBS, SPICES AND FLAVOURINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tom Stobart | 240 pages | 14 Dec 2017 | Grub Street Publishing | 9781910690499 | English | London, United Kingdom Herbs, Spices and Flavourings PDF Book Free Sample.. The dried berries are slightly larger than peppercorns and impart a combination flavor of cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and pepper — hence the name allspice. For large batches of herbs and spices, a spice mill or a coffee grinder is convenient and quick. Leptotes bicolor Paraguay and southern Brazil Lesser calamint Calamintha nepeta , nipitella , nepitella Italy Licorice , liquorice Glycyrrhiza glabra Lime flower, linden flower Tilia spp. Mahleb is an aromatic spice ground from the internal kernel of the sour cherry pits of the mahleb cherry tree, Prunus mahaleb , native to Iran. Used instead of vinegar in salads and sauces when a milder acid is desired or when vinegar is objectionable. Culinary Australian Bangladeshi Indian Pakistani. The authors also focus on conventional and innovative analytical methods employed in this field and, last but not least, on toxicological, legal, and ethical aspects. Baharat is a blend of spices using allspice, black pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, coriander, cumin, nutmeg, and paprika — regional variations may also include loomi, mint, red chili peppers, rosebuds, saffron, and turmeric. Old Bay Seasoning. Twists, turns, red herrings, the usual suspects: These books have it all Often commercially blended with white and black peppercorns, pink peppercorns can be used to season any dish regular pepper would — although it should be noted that pink peppercorns are potentially toxic to small children. Avoid keeping herbs near the stove, in the refrigerator, or in the bathroom. -

Food Allergy

Food Allergens: Challenges and developments Michael Walker EHAI/CIEH Conference 21 May 2015 Science for a safer world LGC – a global company 1842 1996 2003/04 2009/10 Today Laboratory of the Laboratory of Focus on Acquisitions focused on Focus of activities is on Board of Excise the Government science- services (Agowa, intellectual property and founded to protect Chemist dependent Forensic Alliance) new product development excise duty privatised activities payable on Over 35% of revenue Acquisitions focused on tobacco 270 678 within Standards, the pharma and agbio (KBio importation into employees employees only product business in Genomics, QBAS in the UK, became £15m £56m Health Sciences) Laboratory of the turnover turnover Footprint across Europe Government (focused on UK and 50% revenue on products, Chemist with Germany) with KBio acquisition and technical appeal Standards growth functions 1,380 employees £130m turnover Increasing footprint in US and RoW 2,000 employees £200m turnover 2 LGC Laboratory of the Government Chemist Laboratory and Standards Genomics Managed Services Science & Innovation Group Functions LGC’s UK national roles National Measurement Government Chemist Institute (NMI) • The UK’s designated NMI for • Referee Analyst chemical and bioanalytical • Adviser to government and measurement industry on regulations & scientific input • Provides traceable and accurate standards of measurement for use in • Allergen measurement research industry, academic and government “Using sound analytical science in support of policy -

Rejuvenate Like Royalty This Summer with the King's Ginger 'Royal Teacup' Cocktail to Toast the Queen's Coronation Celeb

Rejuvenate like Royalty this Summer with The King’s Ginger ‘Royal Teacup’ Cocktail To toast the Queen’s Coronation celebrations this summer, Berry Bros. & Rudd have exclusively paired with The Cocktail Lovers to create The King’s Ginger Royal Teacup cocktail. This rejuvenating tipple uses Berry Bros. & Rudd’s very own King’s Ginger liqueur, originally created for King Edward VII in 1903. The King’s Ginger liqueur is one of the spirits to be showcased by J.J. Goodman, the London Cocktail Club’s leading mixologist, at The Coronation Festival on 11-14 July. This one-off event will be held at Buckingham Palace and will see Goodman demonstrating the best of British cocktails in the Food and Wine Theatre, where attendees can enjoy this sovereign solution to quenching ones thirst during the hazy summer days. Rich and zesty, the uplifting secret to the cocktail is The King’s Ginger, a seductively golden high-strength liqueur with a warming aroma of ginger, lemon, sherbert and golden syrup. The liqueur was created to stimulate and revivify His Majesty during morning rides in his new ‘horseless carriage,’ a Daimler, in 1903 and has been appreciated by bon viveurs, sporting gentlemen and high-spirited ladies ever since. Fresh, zesty and quintessentially English, The Royal Teacup is refreshingly easy to prepare and designed to be served in a teacup. The fizz in the drink lengthens the cocktail, giving a celebratory feel and making it perfect for special occasions. The Royal-Tea Cup Ingredients: 40 ml The King's Ginger 15 ml homemade rhubarb syrup* 25 ml Twinings Lemon & Ginger tea** 10 ml fresh lemon juice 25 ml English sparkling wine Fresh ginger, raspberry and small sprig of mint to garnish Method: Place two big ices cubes in a tea cup. -

Smalls Bigs Sides Desserts

CRISPY GREEK BUTTERMILK CHICKEN 4 Sides Chicken Thighs coated with Bigs FRIES VE 3.5 our own seasoning and CONTEMPORARY GREEK CYPRIOT CUISINE Buttermilk served with Harissa dip SOUVLAKI 12 OVEN BAKED SWEET POTATO WEDGES VE 3.5 An open Kebab served on Hot ZATAR ROASTEDROASTED Baked Pita Bread CHARGRILLED CAULIFLOWERCAULIFLOWER 3.5 TENDERSTEM BROCCOLI VE 3 Choose From Roasted Cauliflower marinated GREEK SALAD V 4 Smalls in Zatar Spices served with a Chargrilled Chicken skewer with Herb & GarlicGarlic Drizzle and toasted Rose Harissa & Tzatziki RAW BOWL VE 4 5 seed crumb KALAMATA OLIVES 2.5 Falafel, Hummus & House Salad AUBERGINE COUS COUS VE 3.5 Ve Gf Ve Gf Taztziki Contains Sesame Seeds Ve CHICKPEA & BLACK OLIVE FRESHLY BAKED HOT PITA 2 Pork Keftedes, Tomato & Fennel FALAFEL 4 Ve Desserts with shredded vegetable slaw BACLAVA, KATAIFI & and our Red Pepper Sauce HUMMUS 3 GALAKTOBOUREKO V 5.5 Ve SUMMER SALAD 12.5 with toasted Pine Nuts & Cumin, Selection of classic Greek Contains Sesame Seeds Chargrilled Asparagus with desserts Ve Gf Contains Sesame Seeds Pea & Hazelnut Pesto CHARGRILLED CYPRIOT Ve GREEK YOGHURT HALLOUMI 4 MELITZANOSALATA 3 LEMON CHEESECAKE 5.5 with Padron Peppers Smoked Aubergine dip TSIPOURA 15.5 With passion fruit drizzle V Gf Ve Gf Gilthead Bream Baked and CHOCOLATE DOUKISSA 5.5 Served in Parchment with Bitter Chocolate Indulgence with CRISPY CALAMARI 5 GREEK YOGHURT TZATZIKI 3 Fennel Seed, Lemon and Crunchy Mosaic Biscuit filling Tapenade and crushed new with a zesty garlic Aioli Cucumber & Mint potatoes COMPRESSED MELON Ve 4 V Gf Submerged in Sauternes Wine PORK KEFTEDES 4 12.5 7.5 Home Made Pork Meatballs TARAMASALATA 3 HOT & STICKY PORK RIBS DESSERT MEZE per person slow cooked with Fennel and Tomato Smoked Cod Roe Slow cooked Pork ribs served with Aubergine & Kalamata A tasting menu of all the desserts Cous Cous above. -

Trofima-Pota2009.Pdf

n • GRAPHIC DESIGN • PACKAGING DESIGN • WEB DESIGN • MULTIMEDIA DESIGΝ • COMMUNICATIONS ΕΦΕΣΟΥ 4, 17121 ΝΕΑ ΣΜΥΡΝΗ T : 210 9324440 F : 210 9324473 E : [email protected] W: tangram.gr • Επίβλεψη και τήρηση βιβλίων όλων των κατηγοριών • Μηχανοργάνωση Λογιστηρίων • Σύµβουλοι • Χρηµατοοικονοµικές Μελέτες • Φοροτεχνικές Εφαρµογές • Νοµική Υποστήριξη: Άννα Μπούντα & Συνεργάτες Υπεύθυνος ανάλυσης: Πάρης Μήτσου Φιλολάου 188Α 11634 Αθήνα. Τηλ.: 210 7561605 - 210 7561430 Fax: 210 7511092 www.diktio.com.gr e-mail:[email protected] ΧΑΙΡΕΤΙΣΤΗΡΙΑ ΜΗΝΥΜΑΤΑ GREETING MESSAGES Η ιστορία του κλάδου δείχνει ότι η οργανωµένη βιοµηχανία τροφίµων αντα- ποκρίνεται στις προκλήσεις των καιρών, επενδύοντας σε σύγχρονες γραµµές παραγωγής, σε ποιότητα, σε καινοτόµα προϊόντα και, µέσα σε πλαίσιο ισχυρού ανταγωνισµού, δηµιουργώντας ανάπτυξη και θέσεις εργασίας. Σήµερα, έχουµε το ανώτατο επίπεδο διατροφικής ασφάλειας που υπήρξε ποτέ στον πλανήτη µας κι αυτό οφείλεται στο γεγονός ότι η δουλειά που γίνεται στη βιοµηχανία τροφίµων διεθνώς, είναι τεράστια και άρτια από επιστηµονικής πλευράς. Παρά ταύτα, ο κλάδος αντιµετωπίζει σηµαντικές προκλήσεις και άλλης µορφής που πηγάζουν κυρίως από τις συνεχώς αυξανόµενες απαιτήσεις των καταναλω- τών σε ό,τι αφορά στη διατροφική αξία, στην ασφάλεια και στις περιβαλλοντικές των τροφίµων. Η βιοµηχανία τροφίµων, όµως, είναι αυτή που έχει το µεγαλύτερο συµφέρον να προστατέψει και να ενηµερώσει τον καταναλωτή. Κι αυτό ακριβώς κάνει, αναλαµβάνοντας µάλιστα ηγετικό ρόλο στην προσπάθεια αυτή. Η υπεύθυνη ανταπόκρισή της σ’ αυτές τις ολοένα αυξανόµενες απαιτήσεις, υποχρε- ώνει τον κλάδο να προχωρήσει σε πρόσθετες επενδύσεις σε έρευνα, καθώς και στην υιοθέτηση πρόσθετων διαδικασιών ελέγχων. Τον υποχρεώνει να βελτιώνει σταθερά την ποιότητα της πληροφόρησης που δίνει στους καταναλωτές –από τις πληροφορίες στις συσκευασίες µέχρι την αλήθεια στις διαφηµίσεις. -

Playia-Menu-NEW.Pdf

On the vineyard filled hillside of Omodos village, at an altitude fluctuating between 800 metres (Laona’s summit) and 1060 metres (Afami’s summit), “Oenou Yi – Ktima Vassiliades” proudly maintains the tradition of the Mediterranean vine estate; the “ktima”. Throughout the centuries, the inhabitants of Omodos village have worked tirelessly to create a powerful earth/people bond by taming the mountainous nature of its terroir and created a vast landscape of lush and fruitful vineyards, which now flourish on the slopes of Omodos village. Today, “PLAYIA restaurant” (meaning slope in Greek) honours the very same slopes that have given the region its charismatic terroir. “PLAYIA restaurant” introduces its visitors to the real tastes of Cyprus by pairing contemporary Cypriot regional cuisine, with a hip, vibrant, sophisticated setting, to create a cutting-edge dining experience. For the ultimate in vine-to-table dining, thoughtfully selected wines from the “Oenou Yi – Ktima Vassiliades” cellar are offered with every item on our menu. Enjoy wine in its homeland through a pleasant culinary journey where you can indulge yourself in a unique gastronomic and wine sensation, while overlooking the evergreen vineyards of Omodos village. APPETIZERS THE BREAD BASKET* *(1, 12) Assortment of home-made bread buns HOME-MADE OLIVE TEPENADE* A savoury paste made from Black olives, Green olives, Kalamata olives, with capers, garlic, balsamic vinegar and olive oil *Complimentary SALADS HALLOUMI SALAD *(3, 9, 12, 13) Mix baby leaves, crispy halloumi cheese, dry -

Authentic Flavours of Pafos Authentic Flavours of Pafos

Αυθεντικές γεύσεις της Πάφου Authentic flavours of Pafos Πρόγραμμα Διασυνοριακής Συνεργασίας «Ελλάδα – Κύπρος 2007-13» Προϋπολογισμός Έργου: €560.000 PAFOS REGIONAL BOARD OF TOURISM 7, Athinon & Alexandrou Papagou Avenue, Tolmi Court 101 P.O.Box 60082, 8100 Pafos, Cyprus Tel. +357 26818173 Fax. +357 26944602 Email: [email protected] Αυθεντικές γεύσεις της Πάφου Authentic flavours of Pafos Περιεχόμενα Πρόλογος 8 Αρτοποιήματα/ζυμώματα Γαλένα 66 Πάφος: Ο κήπος της κυπριακής Κολοκοτές 68 γαστρονομίας 10 Πασκιές 70 Τριμιθόπιτες 73 Τα αυθεντικά προϊόντα της Πάφου Σούπες Σούπα λουβάνα 75 16 Τυροκομικά προϊόντα Σούπα τραχανάς 77 27 Προϊόντα αλλαντοποιίας Ψαρόσουπα 79 Ελαιοκομικά 31 Φρούτα και λαχανικά 32 Κρεατικά Προϊόντα της Γεροσκήπου με ευρωπαϊκή Οφτόν της τερατσιάς 81 39 κατοχύρωση Ρέσι 82 40 Γλυκά Ρίφι (κατσικάκι) με χωστές 85 44 Τοπικοί οίνοι Στιφάδο βοδινό 87 Προϊόντα από χυμό σταφιλιού 50 Γλυκά/επιδόρπια Συνταγές Καττιμέρια με μαυρόλαδο 88 Ορεκτικά/σαλάτες/συνοδευτικά Κουραμπιέδες με λουκούμι Γεροσκήπου 91 Αγρέλια με αυγά 55 Μπανάνες στο φούρνο με μέλι και κανέλα 93 Καράολοι στιφάδο 57 Κέικ μπανάνας 93 Κολοκυθοανθοί γεμιστοί 59 Παστελάκι με φυστίκια 95 Κόκκινα μανιτάρια με κρεμμύδια 61 Πορτοκαλόπιτα 97 Σαλάτα με αγγούρι και φυστίκια 63 Τερτζελούθκια με χαρουπόμελο 99 Χωστές με αυγά 65 Χαλβάς κουβαρκαστός με έψημα Καυκαρούες βραστές με λάδι 65 ή χαρουπόμελο 101 ISBN 978-9963-2152-0-1 5 Index Introduction 9 Breads/pastries Galéna 67 Pafos: The garden of Cyprus Kolokotes 69 gastronomy 12 Paskies 71 Crunchy cookies with terebinthus berries -

Barcelona Vermouth Route

The One Drink You Have To Have in Catalonia Sep 27, 2017 13:02 +08 Barcelona Vermouth Route Quimet & Quimet . One of the city’s best known vermouth bars: an absolute must. It serves original tapas, in the Poble Sec district. Bar Mut. Just a stone’s throw from La Pedrera, it serves high-quality tapas. Robert de Niro never fails to stops by when he visits Barcelona! Bodega 1900.This establishment is owned by chef Albert Adrià, Ferran Adrià’s brother. Vermouth flows through the veins of this gastronomic temple. Lo Pinyol. Vermouth to accompany pinxos, cold meat and cheese. It is located in the busy Gràcia district, one of the most Bohemian areas of the city. Morro Fi. A tiny bar that very clearly bears the ‘Made in Barcelona’ stamp. Popular with families and young people on Sunday lunchtimes. Bar Carmelitas . This restaurant managed by chef Xavier Pellicer, located in the heart of the city’s El Raval district, revives the spirit of the 1920s. Bodega La Puntual. Very close to the Picasso Museum; a large space where you can enjoy vermouth at any time. Bodega El Chigre. This original tavern next to the Basilica of Santa Maria del Mar offers a range of tapas featuring typical Catalan and Asturian cuisine and zero kilometre products. The Catalonia Tourism Board belongs to the regional government of Catalonia (North Eastern Spain) works to promote and consolidate the “Barcelona” and “Catalonia” brands around the world, as a top quality tourist destination with a diverse range of experiences for the regular and luxury traveller in the Asia Pacific region (South East Asia, Australia, New Zealand, India, Japan and South Korea) from Singapore. -

Of Welsh & Borders

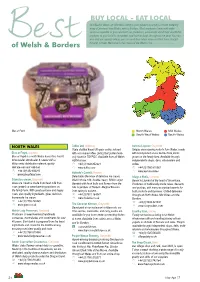

BUY LOCAL - EAT LOCAL Our Best of Welsh and Borders listing is your guide to sourcing a mouth watering array of produce from Wales and its Borders. Most producers have mail order services available or you can meet our producers, passionate about their wonderful produce, at your local food markets and food festivals throughout the year. You can B est also visit our website where you can read their latest news and find links straight of Welsh & Borders through to them.Welcome to the cream of the Welsh crop……………………… Blas ar Fwyd North Wales Mid Wales South West Wales South Wales NORTH WALES Toffoc Ltd, Anglesey Aerona Liqueur, Gwynedd Triple distilled finest UK grain vodka, infused Unique aronia berry products form Wales, made Blas ar Fwyd, Llanrwst with our unique toffee, giving that golden taste with hand-picked aronia berries from plants Blas ar Fwyd is a north Wales based fine food & only found in TOFFOC. Available from all Welsh grown on the family farm. Available through wine retailer, wholesaler & caterer with a ASDA stores. independents shops, delis, wholesalers and Wales-wide distribution network, quality +44 (0)1248 852921 online. delicatessen and cafe-bar. www.toffoc.com +44 (0)1766 810387 +44 (0)1492 640215 Hufenfa’r Castell, Harlech www.aerona.wales www.blasarfwyd.com Delectable dilemmas of delicious ice cream, Siwgr a Sbeis, Llanrwst Glasu Ice cream, Gwynedd Welsh whole milk, double cream, British sugar Based in Llanrwst at the heart of Snowdonia. Glasu ice cream is made from fresh milk from blended with fresh fruits and flowers from the Producers of traditionally-made cakes, desserts cows grazed on award winning pastures on hills & gardens of Harlech. -

Pantheon Menu

Στις τιµές συµπεριλαµβάνεται ο Φ.Π.Α / Prices include V.A.T ΣΑΝΤΟΥΙΤΣ XΑΜΠΟΥΡΓΚΕΡ ΑΛΚΟΟΛΟΥΧΑ ΠΟΤΑ ΚΡΥΑ ΡΟΦΗΜΑΤΑ FRESHLY MADE SANDWICHES HOMEMADE BURGERS ALCOHOLIC DRINKS COLD DRINKS Σπιτικά φτιαγµένα µε τα καλύτερα υλικά Ντόπιο εµφιαλωµένο νερό 500ml Επιλογή Ψωµιού Μπαγκέτα Ολικής Αλέσεως | Τριάρα Εµφιαλωµένες µπύρες / Bottled beers Σερβίρονται µε πατάτες κοµµένες στο χέρι και σαλάτα Carlsberg 330ml €2,50 Local mineral water €1,00 Whole wheat Βaguette | Triara Bread Bread Selection Homemade burgers using only the best ingredients Keo 330ml €2,50 Perrier αεριούχο νερό 330ml Served with hand-cut chips and side salad Leon 250ml €2,00 Perrier sparkling water €2,30 Κυπριακό διάφορα σπέσιαλ Το Αυθεντικό Smirnoff Ice 330ml €3,00 Μίλκσεικς Mixed Cypriot special €5,95 The Original €7,00 Κρασιά / Wines Milkshakes €4,00 Παραδοσιακό Κυπριακό λουκάνικο, λούντζα, µπέικον, Ποτήρι Μπουκάλι Μπιφτέκι από χοιρινό κιµά από φάρµες της περιοχής µαζί µε τη µυστική Με παγωτό βανίλια, σοκολάτα ή φράουλα χαλλούµι, ντοµάτα και αγγούρι Glass Bottle ανάµειξη καρικευµάτων, λιωµένο τυρί, ψηµένα κόκκινα κρεµµύδια, With vanilla, chocolate or strawberry ice cream Traditional Cypriot loukaniko (sausage), with lountza House white, red or rosé €3,50 €13,00 µαρούλι και ντοµάτα. Προσθέστε µπέϊκον ή τυρί €0,50 (smoked ham), bacon, grilled halloumi cheese, fresh tomato Παγωµένο τσάι 330ml Locally sourced farmhouse pork-mince burger with our secret Premium white, red or rosé €5,00 €15,00 and cucumber Iced tea €2,75 ΜΕ selection of herbs and spices, melted cheese, grilled red -

Price List 7/03

NET PRICE LIST J. B. Prince Company, Inc. Effective August 1, 2011 36 East 31st Street, New York, NY 10016 Tentative date for next price list: January 1, 2012 Tel: 212-683-3553 • 800-473-0577 • Fax: 212-683-4488 Office hours: 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Order online: www.jbprince.com Monday through Friday, Eastern Time PRICE CHANGES: Every effort will be made to maintain these prices, PERSONAL CHECKS: Sending a personal check can delay shipment up but due to fluctuating costs, it may be necessary to change them without to 2 weeks for bank clearance. notice. SHIPPING CHARGE: Actual shipping charges will be added. GUARANTEE: If you are not completely satisfied, we will accept the We do not charge “handling” or “packing” fees. prompt return of any unused item for replacement, exchange or full refund of the purchase price. CANADA PRICES: Our prices are in U.S. Dollars. Please make sure checks or RETURNS: Please contact us for return authorization. money orders are in U.S. Currency. SHIPPING COSTS: Most prices are F.O.B. our DELIVERY: Normally we ship UPS where warehouse in New York City. Some are drop shipped Our prices are not available. Allow 1 to 2 weeks for delivery. Faster deliv- directly from the manufacturer. See below for details on ery can be arranged. Contact us for rates. shipping costs. “manufacturer’s list” CUSTOMS & TAXES: Your customs broker or UPS will ORDERING: By phone (800 473-0577) from 9:00 A.M. to prices. They are as collect from you when the package is delivered.