Prithviraj Raso Book in English Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval History

CONTENTS MEDIEVAL HISTORY 1. MAJOR DYNASTIES (EARLY ....... 01-22 2. EARLY MUSLIM INVASIONS ........23-26 MEDIEVAL INDIA 750-1200 AD) 2.1 Early Muslim Invasions ..................24 1.1 Major Dynasties of North ...............02 The Arab Conquest of Sindh ............... 24 India (750-1200 Ad) Mahmud of Ghazni ............................ 24 Introduction .......................................2 Muhammad Ghori ............................. 25 The Tripartite Struggle ........................2 th th The Pratiharas (8 to 10 Century) ........3 3. THE DELHI SULTANATE ................27-52 th th The Palas (8 to 11 Century) ...............4 (1206-1526 AD) The Rashtrakutas (9th to 10th Century) ....5 The Senas (11th to 12th Century) ............5 3.1 The Delhi Sultanate ......................28 The Rajaputa’s Origin ..........................6 Introduction ..................................... 28 Chandellas ........................................6 Slave/Mamluk Dynasty (Ilbari ............ 28 Chahamanas ......................................7 Turks)(1206-1526 AD) Gahadvalas ........................................8 The Khalji Dynasty (1290-1320 AD) ..... 32 Indian Feudalism ................................9 The Tughlaq Dynasty (1320-1414 AD) .. 34 Administration in Northern India ........ 09 The Sayyid Dynasty ........................... 38 between 8th to 12th Century Lodi Dynasty .................................... 38 Nature of Society .............................. 11 Challenges Faced by the Sultanate ...... 39 Rise -

Essentials of Hindutva.Pdf

Hindutva SwatantryaVeer V.D. Savarkar Essentials of Hindutva Swatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883 – 1966) What is in a name? We hope that the fair Maid of Verona who made the impassioned appeal to her lover to change 'a name that was 'nor hand, nor foot, nor arm, nor face, nor any other part belonging to a man' would forgive us for this our idolatrous attachment to it when we make bold to assert that, 'Hindus we are and love to remain so!' We too would, had we been in the position of that good Friar, have advised her youthful lover to yield to the pleasing pressure of the logic which so fondly urged 'What's in a name? That which we call a rose would smell as sweet by any other name!' For, things do matter more than their names, especially when you have to choose one only of the two, or when the association between them is either new or simple. The very fact that a thing is indicated by a dozen names in a dozen human tongues disarms the suspicion that there is an invariable connection or natural connection or natural concomitance between sound and the meaning it conveys. Yet, as the association of the word with the thing is signifies grows stronger and lasts long, so does the channel which connects the two states of consciousness tend to allow an easy flow of thoughts from one to the other, till at last it seems almost impossible to separate them. And when in addition to this a number of secondary thoughts or feelings that are generally roused by the thing get mystically entwined with the word that signifies it, the name seems to matter as much as the thing itself. -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title The slave dynasty (1206-1290) Module Id I C/ OIH/ 20 Knowledge in Medieval Indian History and Delhi Pre-requisites Sultanate To know the History of Slave/ Mamluk dynasty Objectives and their role in Delhi sultanate Qutb-ud-din Aibak / Iltutmish/ Razia / Balban / Keywords Slave / Mamluk / Delhi Sultanate E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The Sultanate of Delhi, said to have been formally founded by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, one of the Viceroys of Muhammad Ghori. It is known as the Sultanate of Delhi because during the greater part of the Sultanate, its capital was Delhi. The Sultanate of Delhi (1206–1526) had five ruling dynasties viz., 1) The Slave dynasty (1206-1290), 2) The Khilji Dynasty (1290–1320) 3), The Tughlaq Dynasty (1320–1414), 4) The Sayyad Dynasty (1414–1451) and 5) The Lodi dynasty (1451–1526). The first dynasty of the Sultanate has been designated by various historians as ‘The Slave’, ‘The Early Turk’, ‘The Mamluk’ and ‘The Ilbari’ 2. Slave/Mamluk Dynasty 2.1. Qutb-ud-din Aibak (1206 – 1210) Qutb-ud-din Aibak was the founder of the Slave/Mamluk dynasty. He was the Turk of the Aibak tribe. In his childhood he was first purchased by a kind hearted Qazi of Nishapur as Slave. He received education in Islamic theory and swordmanship along with the son of his master. When Qazi died, he was sold by his son to a merchant who took him to Ghazni where he was purchased by Muhammad Ghori. -

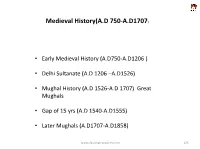

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707)

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707) • Early Medieval History (A.D750-A.D1206 ) • Delhi Sultanate (A.D 1206 –A.D1526) • Mughal History (A.D 1526-A.D 1707) Great Mughals • Gap of 15 yrs (A.D 1540-A.D1555) • Later Mughals (A.D1707-A.D1858) www.classmateacademy.com 125 The years AD 750-AD 1206 • Origin if Indian feudalism • Economic origin beginning with land grants first by satavahana • Political origin it begins in Gupta period ,Samudragupta started it (samantha system) • AD750-AD950 peak of feudalism ,it continues under sultanate but its nature changes they allowed fuedalism to coexist. www.classmateacademy.com 126 North India (A.D750 –A.D950) Period of Triangular Conflict –Pala,Prathihara,Rashtrakutas Gurjara Prathiharas-West Pala –Pataliputra • Naga Bhatta -1 ,defends wetern border • Started by Gopala • Mihira bhoja (Most powerful) • Dharmapala –most powerful,Patron of Buddhism • Capital -Kannauj Est.Vikramshila university Senas • Vijayasena founder • • Last ruler –Laxmana sena Rashtrakutas defeated by • Dantidurga-founder, • Bhakthiyar Khalji(A.D1206) defeated Badami Chalukyas (Dasavatara Cave) • Krishna-1 Vesara School of architecture • Amoghvarsha Rajputs and Kayasthas the new castes of Medival India New capital-Manyaketa Patron-Jainism &Kannada Famous works-Kavirajamarga,Ratnamalika • Krishna-3 last powerful ruler www.classmateacademy.com 127 www.classmateacademy.com 128 www.classmateacademy.com 129 www.classmateacademy.com 130 www.classmateacademy.com 131 Period of mutlicornered conflict-the 4 Agni Kulas(AD950-AD1206) Chauhans-Ajayameru(Ajmer) Solankis Pawars Ghadwala of Kannauj • Prithviraj chauhan-3 Patronn of Jainsim Bhoja Deva -23 classical Jayachandra (last) • PrthvirajRasok-ChandBardai Dilwara temples of Mt.Abu works in sanskrit • Battle of Tarain-1 Nagara school • Battle of tarain-2(1192) Chandellas of bundelKhand Tomars of Delhi Kajuraho AnangaPal _Dillika www.classmateacademy.com 132 Meanwhile in South India.. -

The Last Hindu Emperor Prithviraj Chauhan and the Indian Past, 1200-2000 1St Edition Download Free

THE LAST HINDU EMPEROR PRITHVIRAJ CHAUHAN AND THE INDIAN PAST, 1200-2000 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Cynthia Talbot | 9781107544376 | | | | | The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Chauhan and the Indian Past, 1200-2000 All Languages. According to the 15th-century historian Jonaraja"naga" here refers to elephants. Govind Singh is currently reading it Jun 01, According to Tabaqat-i Nasirihe gathered a well-equipped army ofselect AfghanTajik and Turkic horsemen over the next few months. Over time, Prithviraj came to be portrayed as a patriotic Hindu warrior who fought against Muslim enemies. Both the texts state that he was particularly proficient in archery. Hardcoverpages. Manali marked it as to-read Sep 29, In response, Jagaddeva told Abhayada that he had concluded a treaty with Prithviraj with much difficulty. First published inthis selection was created to provide the general reader and university Singh believes that no such conclusion can be drawn from Minhaj's writings. The Mohils are a branch of the Chauhans the Chahamanasand it is possible the inscriptions refer to the battle described in Prithviraj Raso. The Provincial Geography of India series was created during the early part of the twentieth Singhpp. Nevertheless, the 19th century British officer James Tod repeatedly used this term to describe Prithviraj in 1200-2000 1st edition Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han. Prithviraj was not able to annex the Chandela territory to his kingdom. After his victory, Prithviraj sacked Mahoba. Anil Sinha added it Apr 24, Later, Paramardi's son recaptured Mahoba. Despite being overthrown, however, his name and story have evolved 1200- 2000 1st edition time 1200-2000 1st edition a historical symbol of India's martial valor. -

Muslim Invasions on India in the Medieval Period and Its Impact

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH ISSN NO : 2236-6124 Muslim Invasions on India in the Medieval Period and Its Impact S.M. Gulam Hussain, Lecturer in History Department of History, Osmania College (A), Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh ABSTRACT: Medieval period is an important period in the history of India because of the developments in the field of art and languages, culture and religion. In the early medieval age India was on the threshold of phenomenal changes in the domains of polity, economy, society and culture. The impact of these changes is visible even today influencing the growth of India as one nation. Early Medieval period witnessed wars among regional kingdoms from north and south India where as late medieval period saw the number of Muslim invasions by Mughals, Afghans and Turks. The impact of Islam on Indian culture has been inestimable. It permanently influenced the development of all areas of human endeavour- language, dress, cuisine, all the art forms, architecture and urban design, and social customs and values. This paper describes the Muslim invasions on India in the Medieval Period and its impact. Keywords: Medieval period, Culture, Religion, Muslim invasions, Inestimable 1. INTRODUCTION: Medieval period lasted from the 8th to the 18th century CE with early Medieval period from the 8th to the 13th century and the late medieval period from the 13th to the 18th century. Early Medieval period witnessed wars among regional kingdoms from north and south India where as late medieval period saw the number of Muslim invasions by Mughals, Afghans and Turks. In the early medieval age India was on the threshold of phenomenal changes in the domains of polity, economy, society and culture. -

CLASS-7 HISTORY CHAPTER-1 Tracing Changes in Medieval Period -By Vineet Kaur

CLASS-7 HISTORY CHAPTER-1 Tracing Changes in Medieval Period -by Vineet Kaur SHORT ANSWER TYPE QUESTIONS Q1. What do literary resources include? Ans. Literary sources include autobiographies, biographies, chronicles and travelogues. Q2. Into how many periods can the medieval period be divided? Ans. Medieval period can be divided into 2 periods: - 1) Early medieval period (8th -13th century). 2) Late medieval period (13th-18th century). Q3. Who wrote Prithviraj Raso? What does it describe? Ans. Prithviraj Raso was written by Chandbardai. It describes the life and adventures of Prithvi Raj Chauhan, Rajput ruler of Delhi and Ajmer. Q4. Why was Bhakti Movement considered a major development in India? Ans. One of the major developments of this period was the Bhakti movement. This was a form of prayer in which the devotees would worship God without the help of priests and elaborate rituals. LONG ANSWER TYPE QUESTIONS Q1. Briefly describe the archaeological resources. Ans. The description of archaeological resources are as follows: - 1) Inscriptions - Inscriptions are found on the coins, pillars, monuments and seals. These provide short but important information on various aspects. 2) Monuments - Monuments like tomb, Forts, mosques and temples provide a lot of information about the period. 3) Paintings - In the medieval period two kinds of paintings emerged. They were the mural and miniature paintings. 4) Coins - Coins provide information about the names and dates or different rulers. They also give us an idea of the economic conditions prevailing during that time. Q2. How do travelogues help in reconstruction of history? Ans. Travelogues play a very important role in reconstructing history as many Muslim and European travelers visited India and wrote an account of the travels. -

INDIAN HISTORY-II Multiple Choice Questions

HIS4(4) B06 INDIAN HISTORY-II Multiple Choice Questions 1. Who wrote An Introduction to the Study of Indian History? (a) R.S. Sharma (b) D.D. Kosambi (c) D. N. Jha (d) Mortimer Wheeler 2. The famous paper entitled “Was There Feudalism in Indian History? belongs to (a) B N S Yadava (b) D. C. Sircar (c) Harbans Mukhia (d) D.N. Jha 3. Which among the following is/are the structural models related to the early Indian society? (a) Polity based on Feudal System (b) Theory of Integrated polity (c) Theory of Segmentary State (d) All the above 4. What is Samanta system (a) A system of taxation (b) A political system based on hierarchy of vassals (c) A system of measuring land (d) A system of coinage in medieval India 5. With which dynasty did Indian Muslims start entering into positions of power? (a) Tughluqs (b) Ilbaris (c) Khaljis (d) Sayyids 6. Which tax was not permitted by the shariat? (a) Agriculture tax (b) Tax on non-Muslims (c) Commercial tax (d) Marriage tax 7.Which was not true about jizya? (a) It was a tax on non-Muslims. (b) Brahmins were generally exempted from it. (c) The first ruler to collect it in India was Firoz Tughluq. (d) It never yielded any substantial revenue. 8. The iqtadars during the period of the Delhi sultanate were also known as (a) maliks (b) muqtis (c) mamlatdars (d) munhias 9. How many jitals made up a tanka? (a) 44 (b) 40 (c) 48 (d) 46 10. Who is identified as Tamerlane? (a) Mahmud of Ghazni (b) Muhammad of Ghur (c) Timur (d) Chengiz Khan 11. -

Honsaj-Vol-15.Pdf

3501 the subject, the circumstances, the period when it is written, the motive or objective, if any, and such other similar factors. We know that most of the books written by renowned and esteemed persons enjoin a very high reputation amongst the historians and therefore, what they have written, may not easily be ignored. However, we also can not ignore the fact that while writing a history book the author sometimes is influenced by the institution or body who has employed him, some times though free lancer, but has expressed his views and findings according to his own appreciation without having occasion of cross-check by other experts and some times the purpose of the writing may have domination over independent objective and fair assessment and instead of simply placing on record the events of history straight, he mould facts giving a totally different shade and colour. A Court of law, when comes across such documents which are placed for adjudication of an event or disputed fact of historicity, has to proceed with extreme caution and careful manner. It cannot just treat the views expressed by the historians as a gospel truth. We have noticed and shall demonstrate what was said two centuries back, was widely corrected with the passage of time and in modern times, a considerable number of persons have come forward with well documented and discussed version canvassing a totally different view which also cannot be brushed aside easily but worth consideration. Obviously, the historians, past and present, are not eye witnesses of the historical events, but by sheer dent of diligence and intelligensia, they have analysed past events in the light of material available to them to explain historical events and have tried to apprise the people thereof. -

Alampur, Garuda, Bada and Vira Temples, $75.00

DONALDSON ARCHIVE DONALDSON ARCHIVE IMAGE SITE SETS FOR SALE ANDHRA PRADESH SBHN-1 58 images, Bihar/Bengal sculpture, Buddhist; $174 .00 SBHN-2 107 images Bihar/Bengal sculpture, Hindu, $321.00. , ALM-1 25 images; Alampur, Garuda, Bada and Vira temples, $75.00 ALM-2 28 images, Alampur, Kumara T, Padma T, sculpture court; $84.00 ALS` 27 images, Alampur, Svarga Brahma complex, 680 C.E. $81.00 ALV 35 images, Alampur, Vira Brahma T. c. 680-95 C.E. $105.00. APG 44 images, Gallavali, Kumaresvara temple, c. 10th C. $105.00 APN 39 images, Narayanapuram, NilakanthesvaraT. 10th C , $117.00 ARV-1 39 images, Amaravati site images , 1st-7th C. $117.00 ARV-2 27 images, Amaravati museum images, $81.00 CRZ 13 images, Chezerla, Kapotesvara temple,, 7th C, $39.00 HMV` 50 images, Hemavati, Doddesvara temple, 8th-11th C . $150.00 HNM 28 images, Hanamkonda, Thousand pillar Temple, $84.00 JAY 29 images, Jayati temples, 9th-10th C. $87.00 LPK 44 images, Lepaksi Virabhadra temple complex, c. 16th C MUK-1 365 images, Mukhalingam, Madhukesvara T. 8-9th C $1,095.00 MUK-2 101 images, Mukhalingam, Somesvara temple, 10thC, $303.00. MUK-3 21 images, Mukhalingam , Bhimesvara T, Nagrikatakam, $63.00 NGJ 14 images, Nagarjunakonda, c. 3rd century C.E. $42.00. PLP 67 images, Palampet, Ramappa temple, 1213 C.E. $201.00 PNG 101 images, Panagal, Paccala Somesvara com, 10-15th C, $303.00 PUS 127 images, Puspagiri, temple compound, 10-16th C. $387.00. SAL 24 images, Salihumdam, Buddhist site, c. 10th C $72.00. -

WORKSHEET, Class 7Th,History, Chapter 2,S.St. A.Answer These Questions:- Answer:- 1 Al-Beruni

WORKSHEET, Class 7th,History, chapter 2,S.St. A.Answer these questions:- Answer:- 1 Al-Beruni. Answer:- 2 Dantivarman was the founder of Rashtrakut dynasty. Answer:- 3 Rajputs are Well known for their bravery, honour and prestige in Indian history.Rajputs rose to prominence during 9th to 12th centuries. Answer:- 4 Rashtrakuta Dynasty built the Kailash temple at Ellora. B.Choose the right answer:- 1.Gopal 2.none of these 3.big landlords or warrior chiefs. 4.Prithviraj Raso C.Fill in the blanks:- 1.Kannauj 2.prithviraja-iii 3. Prithviraj- raso 4. Vishnu , Adivaraha D.Distinguish between: 1.The Rashtrakutas and the Palas The Rashtrakutas- Rashtrakutas were initially subordinate to the Chalukyas of Karnataka. In 753 AD Dantidurga a Rashtrakuta Chief declared independence from his Chalukya overlord. They performed a ritual, called 'Hiranya-garbha' (the golden womb) with the help of Brahmanas to become a Kshatriya king. In this way, Dantivarman, also known as Dantidurga became the founder of this dynasty. His capital was at Manyakheta or Malkhed, near modern Sholapur in Maharashtra. The Palas- The Pala dynasty was founded by Gopala. He was an elected king chosen by the nobles because the previous ruler had died issuless. His capital was at Pataliputra.Dharampala and 'Devapala' were the famous rulers of this dynasty. They ruled around the3 regions of Bihar, Bengal and parts of Orissa and ASsam with many ups and downs for over four centuries. In the middle of the 12th century Vijayasena defeated the Palas. 2.Mahmud of Ghazni and Muhammad Ghori. Mahmud of Ghazni- Mahmud of Ghazni had started his invasions in India during the period when the Rajput power had declined.